Yves here. Most Western governments like to pretend that that they are not in the business of industrial policy. In fact, they clearly are, in the form of numerous subsidies, like interest rate breaks, tax credits, subsidies, borrowing guarantees and large and lax government purchasing schemes. So in the US, the preferred sectors include the medical care,1 real estate, higher education, and arms makers.

So then the question becomes, if governments were to get past neoliberal/libertarian and decide to engage in overt industrial policy, how does one go about it? There’s a solid case that tariffs are not a great tool. This look at how the Chinese boosted their shipbuilding industry via investment and production subsidies, which did indeed generate a big gain in global markets share. The post then looks at whether there was a welfare benefit in China.

By Panle Barwick, The Todd E. and Elizabeth H. Warnock Distinguished Chair Professor, University of Wisconsin – Madison; Myrto Kalouptsidi, Professor of Economics, Harvard University; and Nahim Bin Zahur. Originally published at VoxEU

Industrial policy has been used by many countries throughout history. Yet, it remains one of the most contentious issues among policymakers and economists. This column outlines a theory-based empirical methodology that relies on estimating an industry equilibrium model to measure hidden subsidies, assess their welfare consequences for the domestic and global economy, and evaluate the effectiveness of different policy designs. It applies the methodology on China’s recent policies to promote its shipbuilding industry to dissect the impact of such programmes, what made them (un)successful, and to explain why governments have chosen shipbuilding as a target.

Industrial policy refers to a government agenda to shape industry structure by promoting certain industries or sectors. Although casual observation suggests that industrial policy can boost sectoral growth, researchers and policymakers have not yet mastered predicting or evaluating the efficacy of different types of government interventions, nor how to measure the overall short-run and long-run welfare effects (Juhasz et al. 2023, Millot and Rawdanowicz 2024). In this column, we focus on one particular example of industrial policy: the shipbuilding sector.

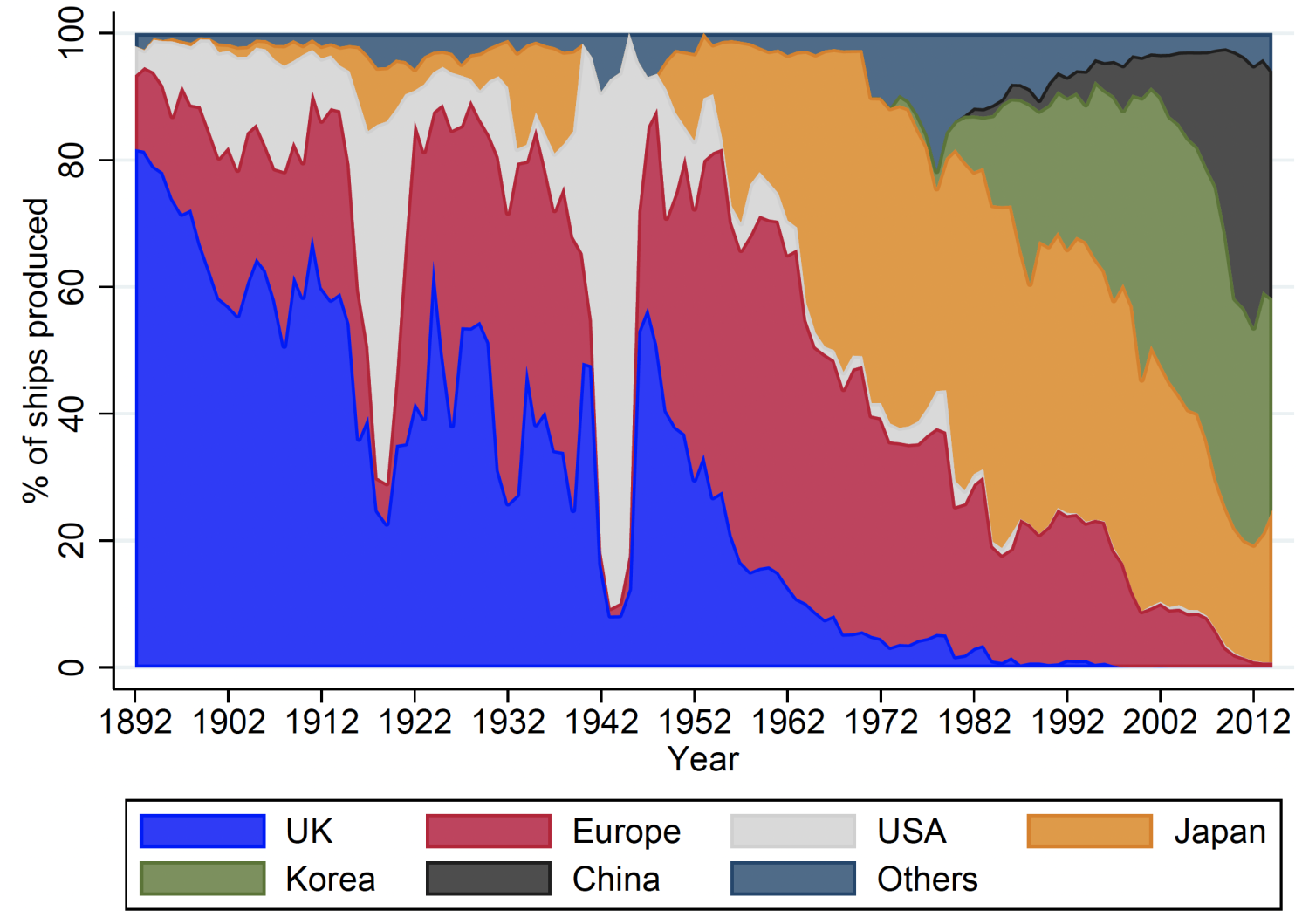

The history of shipbuilding is as tumultuous as the seas themselves. Shipbuilding has always held an allure for governments, in its real and perceived interactions with industrialisation, maritime trade, and military strength (Stopford 2009). Figure 1 shows the succession of countries as the world’s dominant shipbuilding nation. The UK held the lion’s shareof the industry for the better part of the 19th and 20th centuries, fending off competition from other Western European economies (mainly Germany and Scandinavia) at times. After WWII, it is swiftly overtaken by Japan, which prevails as aworld leader until the 1980s, when South Korea dominates the global market.

Figure 1 Share of commercial ships produced by each country, 1892-2014

Note: This figure plots the world market share in terms of the number of ships delivered from 1892-2014 for the major ship producing countries.

Source: Data for 1892-1997 was obtained from historical issues of the World Fleet Statistics published by Lloyd’s Register, while the data from 1998 onwards is based on Clarksons data. We group together all European shipbuildingcountries except for the UK under ‘Europe’.

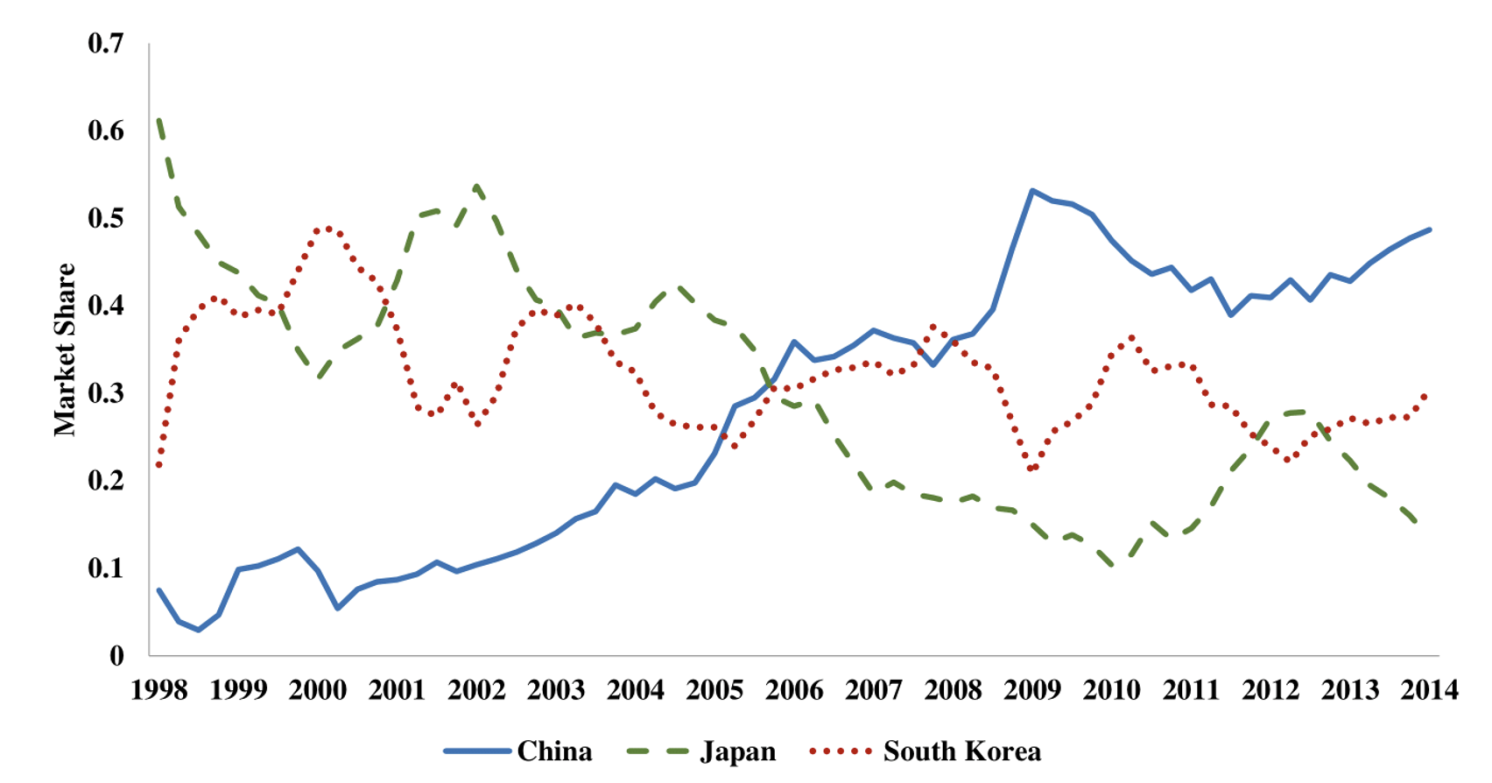

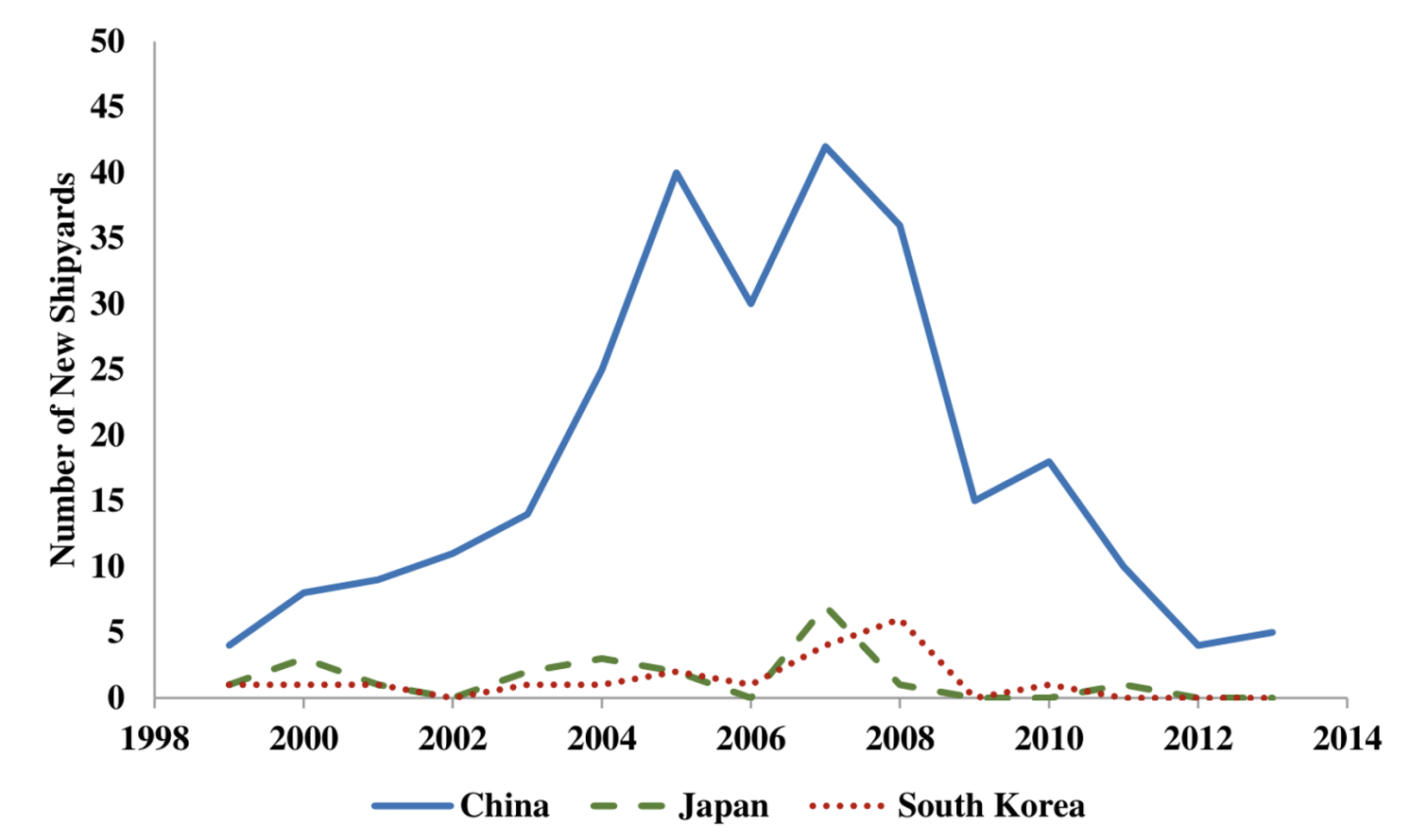

In the 2000s, China entered the shipbuilding scene. In 2002, former Premier Zhu inspected the China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC), one of the two largest shipbuilding conglomerates in China, and pointed out that “China hopes to become the world’s largest shipbuilding country (in terms of output) […] by 2015.” Within a few years, China overtook Japan and South Korea to become the world’s leading ship producer in terms of output. Figure 2, PanelA shows the rise in China’s global market share of shipbuilding by plotting China’s total shipbuilding output as a share of global output. China’s national and local governments provided numerous subsidies for shipbuilding, which we classify into three groups. First, below-market-rate land prices along the coastal regions, in combination with simplified licensing procedures, acted as ‘entry subsidies’ that incentivised the creation of new shipyards. As shown in Panel B of Figure 2, between 2006 and 2008, the annual construction of new shipyards in China exceeded 30 new shipyards per year; in comparison, during the same time period, Japan and South Korea averaged only about one new shipyard per year each.

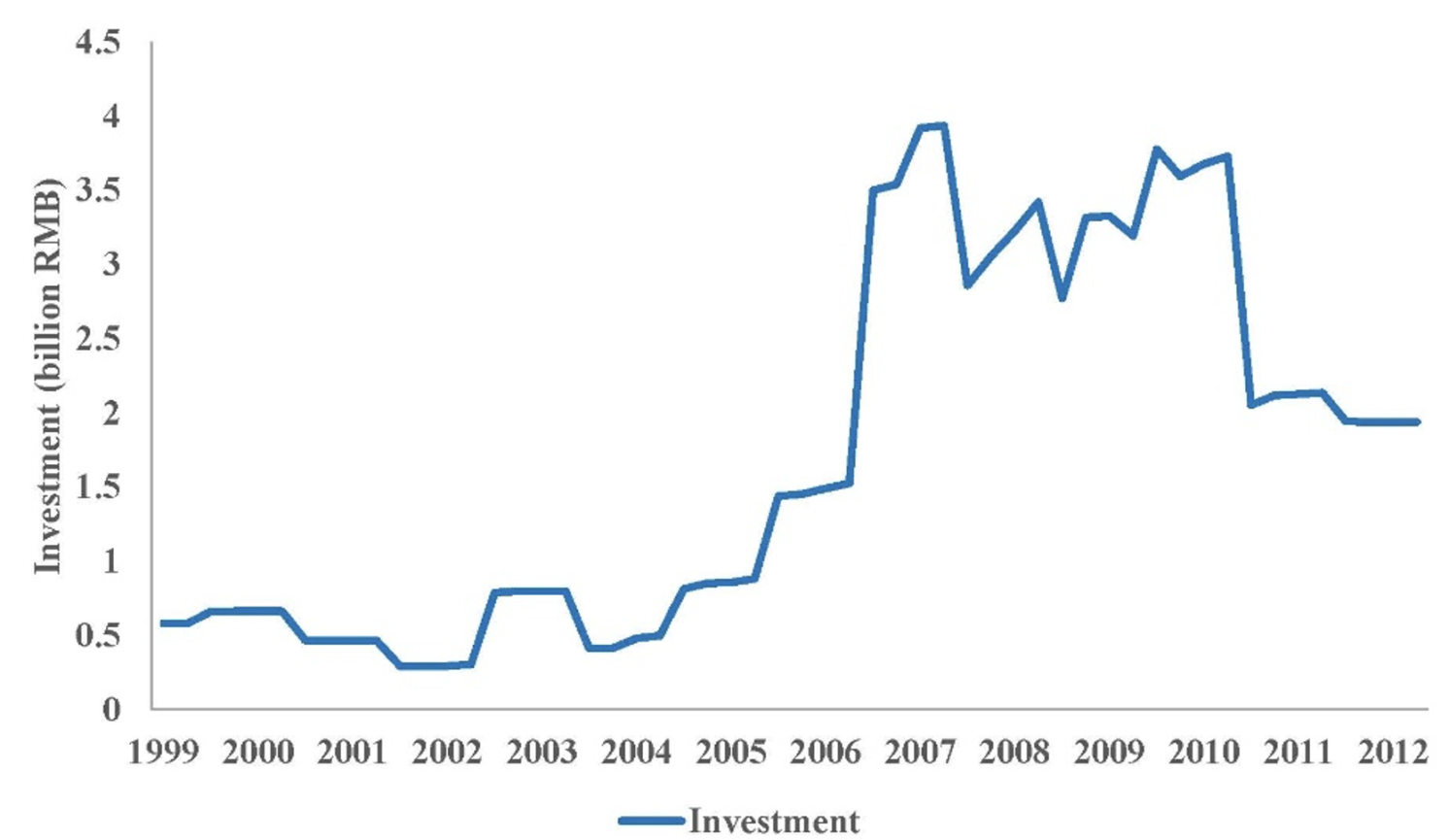

Second, regional governments set up dedicated banks to provide shipyards with ‘investment subsidies’ in the form offavourable financing, including low-interest long-term loans (a common industrial policy tool, as illustrated also by the programmes in Japan and South Korea) and preferential tax policies. China’s rise in total capital invested in shipyards is illustrated in Panel C of Figure 2. Third, China’s government also employed ‘production subsidies’ of various forms, such as subsidised material inputs, export credits, and buyer financing. The government-buttressed domestic steel industryprovided cheap steel, which is an important input for shipbuilding. Export credits and buyer financing by government-directed banks made the new and unfamiliar Chinese shipyards more attractive to global buyers.

Figure 2 The rapid expansion of China’s shipbuilding industry

A) Market share

B) Number of new shipyards

C) Investment

Notes: Market shares by country are computed from quarterly ship orders. Number of new shipyards is computed annually and by country. Industry aggregate quarterly investment by Chinese shipyards in billions of 2000 yuan.

Source: Barwick et al. (2024), using data from Clarksons Research and China’s National Bureau of Statistics.

The combination of these policies was followed by a sharp expansion in China’s shipbuilding production, market share, and capital accumulation. China’s market share grew from 14% in 2003 to 53% by 2009, while Japan shrunk from 32% to 10% and South Korea from 42% to 32%. Then came the Great Recession of 2008-09, which drove the global shipping industry to a historic bust. The large number of new Chinese shipyards exacerbated low capacity utilisation and contributed to plummeting global ship prices. The effectiveness of China’s industrial policy was questioned. In response to the crisis and in an effort to promote industry consolidation, the government unveiled the “2009 Plan on Adjusting and Revitalizing the Shipbuilding Industry” that resulted in an immediate moratorium on entry and subsequently shifted support towards only selected firms in an issued ‘whitelist’.

Kalouptsidi (2018) and Barwick et al. (2024) study the impact of China’s 21st century shipbuilding programme on industry evolution and global welfare. To our knowledge, this work is the first attempt at evaluating quantitatively industrial policy in shipbuilding globally and among the first papers employing the structural industrial organisation methodology to understand the welfare implications and effective design of industrial policy more generally.

We build a model that is flexible enough to capture rich dynamic features of a global market for ships. On the demand side, a large number of shipowners across the world decide whether to buy new vessels. Their willingness-to-pay for new ships depends on present and expected future market conditions, notably on world trade and the current fleet level. On the supply side, shipyards located in China, Japan, and South Korea (which account for 90% of world production) decide how many ships to produce, by comparing the market price of a ship and its production costs. In addition, shipyards decide whether to enter by comparing their lifetime expected profitability to entry costs, which include the costs to set up a new firm (such as the cost of land acquisition, shipyard construction, and any initial capital investments) and the implicit cost of obtaining regulatory permits. They exit if expected profitability from remaining in the industry falls below a given threshold, capturing the shipyard’s ‘scrap’ value (that is, the proceeds from liquidating the business, as well as any option values of the firm). Firms also invest to expand future production capacities. For estimation, we employ a rich dataset consisting of firm-level quarterly ship production between 1998 and 2014, firm-level investment, entry andexit, and new ship market prices by ship type (containerships, tankers, and dry bulk carriers, which together account for 90% of global sales).

Our estimates suggest that China provided $23 billion in production subsidies between 2006 and 2013. This finding is driven by the cost function obtained from this analysis, which exhibits a significant drop for Chinese producers equal to about 13-20% of the cost per ship. Simply put, Chinese shipbuilding firms were ‘over’-producing after 2006 compared to our prediction of output without subsidies. Altogether, China provided $91 billion in subsidies along all three margins – production, entry, and investment – between 2006 and 2013. Notably, entry subsidies were 69% of total subsidies, while production subsidies were 25%, and investment subsidies accounted for the remaining 6%. These estimates reflect the fact that shipbuilding firms ‘over-entered’ (recall the astonishing entry rates during the boom years of 2006-2008) and ‘over-invested’ (recall the striking increase in investment during the bust), as shown earlier in Figure 2.

Our structural model suggests that China’s industrial policy in support of shipbuilding boosted China’s domestic investment in shipbuilding by 140%, and more than doubled the entry rate. It also depressed exit. Overall, industrial policy raised China’s world market share in shipbuilding by more than 40%.

Calculating whether this increase in sectoral output should be counted as an increase in welfare is a more delicate question. First, 70% of China’s output expansion occurred via stealing business from rival countries. There is evidence (backed by our cost estimates) that Chinese shipyards are less efficient than their Japanese and South Korean counterparts; thus, the transfer of shipbuilding to China constitutes a misallocation of global resources. Second, China’s industrial policy for shipbuilding led to considerable declines in ship prices. Lower ship prices benefited world ship-buyers somewhat, though only a modest amount accrues to Chinese ship-buyers, as they accounted for a small fraction of the world fleet. Third, and most importantly, although China’s shipbuilding subsidies were highly effective at achieving outputgrowth and market share expansion, we find that they were largely unsuccessful in terms of (domestic) welfare measures. Theprogramme generated modest gains in domestic producers’ profit and domestic consumer surplus. In the long run, thegross return rate of the adopted policy mix, as measured by the increase in lifetime profits of domestic firms divided by totalsubsidies, is only 18%, meaning that for every $1 the government spends, it gets back 18 cents in profitability. In other words, the net return when incorporating the cost to the government was a negative 82%, with entry subsidies explaining a lion’s share of the negative return.

Entry subsidies are wasteful – even by the revenue metric – and lead to increased industry fragmentation and idleness. Entry subsidies attract small and inefficient firms. In contrast, production and investment subsidies increase the backlog and capital stock, which lead to economies of scale and drive down both current and future production costs. As such, they favour large and efficient firms. Indeed, the take-up rate for production and investment subsidies is much higher among efficient firms: 82% of production subsidies and 68% of investment subsidies is allocated to firms that are more efficient than the median firm, whereas only 49% of entry subsidies goes to more efficient firms.

In terms of policy design, a counter-cyclical policy would outperform the pro-cyclical policy that was adopted by a large margin: strikingly, subsidising firms in production and investment during the boom leads to a gross rate of return of only 38% (a net return of -62%), whereas subsidising firms during the downturn leads to a much higher gross return of 70% (a net return of -30%). Moreover, if an ‘optimal whitelist’ is formed – that is, the most productive firms are chosen for subsidies – the gross rate of return would climb to 71%.

Our results highlight why industrial policies have worked better for some countries. In East Asian countries where industrial policy was often considered successful, the policy support was often conditioned on firm performance. In contrast, in Latin America where industrial policies often aimed at import-substitution, no mechanisms existed to weed out non-performing beneficiaries (Rodrik 2009). In China’s modern-day industrial policy in the shipbuilding industry, the policy’s return was low in earlier years when output expansion was primarily fuelled by the entry of inefficient firms but increased over time as the government relied on ‘performance-based’ criteria via its whitelist. Such targeted industrial policy design can be substantially more successful than open-ended policies that benefit all firms.

In terms of the rationale – why China subsidised shipbuilding – the standard arguments for industrial policy do not seem to apply especially well in our setting. The shipbuilding industry is fragmented globally, market power is limited, and markups are slim. Thus, there are no ‘rents on the table’ that, when shifted from foreign to domestic firms, outweigh the cost of subsidies. We find little evidence of learning-by-doing, perhaps because the production technology for the ship types that China expanded the most, such as bulk ships, was already mature. Spillovers to other domestic sectors are limited; in addition, more than 80% of ships produced in China are exported, which limits the fraction of subsidy benefits that is captured domestically. A scenario whereby Chinese output growth forces competitors to exit does not seem first-order either: by 2023, no substantial foreign exit occurred.

Our analyses point to two alternative potential rationales. First, as China became the world’s biggest exporter and a close second largest importer during our sample period, transport cost reductions from increased shipbuilding and reduced shipping costs can lead to substantial increases in its trade volume. Our estimates suggest that China’s industrial policy expanded the global shipping fleet, reduced freight rate, and raised China’s annual trade volume by 5% ($144 billion) between 2006 and 2013. This increase in trade was large relative to the size of the subsidies (which averaged $11.3 billion annually between 2006 and 2013). Of course, ‘more trade’ does not translate directly into economic well-being, but the relative magnitudes are suggestive. Second, both military and commercial deliveries at shipyards that produce military ships experienced a multi-fold increase, although military production appeared to have accelerated after the financial crisis and continued to increase throughout the sample period, providing suggestive evidence that China’s supportive policy might have benefited its military production as well.

See original post for references

_____

1 Not just big R&D subsidies but also the huge tax break of employer-paid health insurance being a tax deduction to the company but not taxable income to the recipient, like most other employer-provided benefits.

Amusingly, this is a great illustration of the difficulty that western-trained analysts have with coming to grips with socialist systems. “Overcapacity”, when you have forward planning well into the next decade, is pretty much irrelevant. And starting lots of new companies (that are generally inefficient until they work out the bugs) is how you discover the real talent to focus future winnowing on. China’s “infamous” ghost cities are all full now, for example. They just plan ahead. And China now has the extra military capacity it clearly needs now, just as Russia retained its military “overcapacity” in spite of the privatization push in the 90s, and is using it to good effect now. China understands that the government doesn’t need profits, and it does need to protect and support its population. And polling by both western and Chinese pollsters indicates that that population is ecstatic about it.

Wise words, Mr. Zapster, ni dong shi, Mike Liston

https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202410/1320959.shtml

October 10, 2024

China secures 70% of global green ship orders in first three quarters of 2024: report

Major indexes of China’s shipbuilding industry have risen steadily in the first three quarters this year, data released by the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT) showed on Thursday. China captured more than 70 percent of global green ship orders in the first three quarters, according to China Central Television Station (CCTV).

Data shows from January to September, China completed 36.34 million deadweight tons (DWT) in shipbuilding, an 18.2 percent increase year-on-year, while securing 87.11 million DWT in new orders, up 51.9 percent. By the end of September, the total orders on hand reached 193.3 million DWT, a 44.3 percent rise.

During this period, China accounted for 55.1 percent of global ship completions, 74.7 percent of new orders, and 61.4 percent of the global holding orders, according to the MIIT.

China captured more than 70 percent of global green ship orders in the first three quarters, covering all major vessel types. Eco-friendly technology, high-value ships, and proprietary innovations have become a key trend in the country’s shipbuilding sector, the CCTV reported.

China took the lead globally in new orders for 14 out of 18 major shipbuilding-related types, with shipyards exceeding their annual targets ahead of schedule amid rapidly growing market demand, according to CCTV…

Keep in mind that the special focus on shipbuilding for China came as the United States began a policy of containment towards China. China’s shipbuilding industry was meant to make the country self sufficient in shipping and included even the mastery of stirling engine design and construction, special craft for deep-sea exploration, arctic exploration, resource exploration and development, wind farm and fish farm development…

Also, there is the Chinese building of a space station, advanced global positioning system, ever more complete satellite network, and broad space exploration program after the United States used the Wolf Amendment to prevent China working on a space program with NASA,

China is not about to be contained.

I can see a lot of reasons why China has really pushed ship-building. When they decided to become the world’s factory, they knew that it would require a fleet of ships to transport the manufactured goods from China to the world. But letting foreign shipping firms do this job would be insane as it would give the west a stranglehold over Chinese manufacturing. When your success depends on another’s platform…

As well, it would help keep the costs for Chinese manufacturers low. In the same way that countries like the US used to build highways, hospitals, etc. to lower the costs for American companies, this is China doing the same. The ship owners cannot get greedy and start charging huge markups for shipping lest the gaze of the government fall on them. Better to keep costs low and make it back on volume.

And with ship-building, the skills are transferable to building naval ships as well and the Chinese have built up a huge Navy to protect their shipping. And by building ships and them selling them into the international market you keep those ship workers employed. None of this nonsense about laying off experienced workers for a coupla months and then hoping that they are still there to employ again when demand picks up.

“I can see a lot of reasons why China has really pushed ship-building…”

Important and really fine comment. Keep in mind, US policy has been to contain China since the Obama-Clinton years.

Interesting article overall; it doesn’t really present anything surprising, but sort of backs up some main points that apparently get forgotten, including by the authors? I get the impression they pretty much have “free trade = good” ideological blinders fully on.

* Increase in general welfare (or lack thereof) – I don’t think that’s ever been the argument for subsidizing specific industries. Sure, token “good jobs” may be a side-benefit, but I thought subsidies have always come down to strategic interests of the state. Collective prosperity has to come from the economy as a whole, which is more than the sum of its parts.

* Expansion largely coming from stealing market share – I’m surprised the authors are surprised. I’m pretty sure for anyone that advocates a mercantilist policy, that’s kind of the point.

* Counter-cyclical support is more efficient – not surprising at all, but heavy industry lives or dies by large capital projects that stretch over long time frames. The government actively destabilizing your schedule of returns just because of what real estate or personal services are doing? Won’t help.

* Entry subsidies are wasteful – like zapster, this is another one that struck me as totally missing the point. Of course, more centralized & capital-intensive firms are more efficient. But if you’re standing up a new industry, you don’t have any large efficient firms yet. So how do you get them without something like an entry subsidy? Like, really economists, basic causality isn’t that hard. And even after an industry is more consolidated, they’re discounting all the positive second-order effects of removing entry barriers (e.g. discouraging monopolies, allowing qualitative innovations).

In short, I get the feeling if a business consulted these authors, they would say eliminate the R&D budget & give all but your top couple divisions the Jack Welsh treatment. In the name of “efficiency”, of course.

Disagree. Industrial policy is about promoting sustainable growth so as to increase per capita GDP. For instance, Australia’s CSIRO funds research into industries where Australia could be a top global competitor. One is wine. Hardly of strategic importance.

And at the end of growth comes what?

The ultimate purpose is survival of the species. Industrial policy is just a tool to compete for survival of the group. To this end it can even be useful to shrink a population so as to not overtax its resources. Sustained existence under the best possible conditions for the most people is a long term rationale policy should stick to.

Growth in itself cannot be an aim, as it is unavoidably followed by decay.

Efficiency is always a matter of pov. The US is just finding out what consequences using cheaper labour abroad leads to.

That’s a good counter-point, and I wasn’t aware the Australian wine industry had that much planning behind it. I just figured it grew organically because of their geography.

It’s strange, but maybe my own, weird biases are slipping in. For a healthy economy in the long-term, it’s absolutely necessary to rationalize, structure, and cultivate it. But I guess there’s something about it going beyond cold realism into more idealistic goals like prosperity that makes me leery. Nothing to do with laissez-faire economics, but more complex feelings about the state and mass society in general.

Thanks for the reply; it actually has me thinking about my own worldview in a way I didn’t expect. I’ll have to chew on that more.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/CSIRO

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is an Australian Government agency that is responsible for scientific research and its commercial and industrial applications.

Federally funded scientific research in Australia began in 1916 with the creation of the Advisory Council of Science and Industry. However, the council struggled due to insufficient funding. In 1926, research efforts were revitalised with the establishment of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), which strengthened national science leadership and increased research funding. CSIR grew rapidly, achieving significant early successes. In 1949, legislative changes led to the renaming of the organisation as Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

Notable developments by CSIRO have included the invention of atomic absorption spectroscopy, essential components of the early Wi-Fi technology, development of the first commercially successful polymer banknote, the invention of the insect repellent in Aerogard and the introduction of a series of biological controls into Australia, such as the introduction of myxomatosis and rabbit calicivirus for the control of rabbit populations.

While only mentioned in passing, I do find it quite interesting that the UK went from the largest shipbuilding country to not even viewable on the chart by 2000. And that’s while Japan and S Korea rapidly grew. Japan was equally and island nation and S Korea is roughly (a tad smaller I believe) than the UK, so how do you go from the top of the heap to the bottom?

While I cannot profess to having any meaningful background or understanding of the history or economic history of the UK shipping industry, I do have a get feeling that it rhymes with a lot of industrial experiences mirrored in the US and other UK industries. When I was a kid, I was a news junky and I remember watching the news through the early 1980’s recession and listening to all the announcements of steel plants being closed and steel companies going bankrupt. As I recall, at the time the blame for all these failures were laid at the feet of expensive American UNION labor and the NEW, post WWII, efficient Japanese and S Korean factories.

For the next 20 years of my life I kept hearing recurring versions of this same story as factory after factory is closed. But as an adult I keep wondering how massively profitable companies “all of a sudden” find themselves uncompetitive?!?! My current view is that these situations are often the reverse of industrial policy where investment is encourage… these occur because the businesses decide that those excess profits are better used on anything BUT re-investment in the business. It’s a bleed the patient dry mentality and who cares what happens to the workers who end up unemployed while executive walk away with years of big bonuses and shareholders with dividends and capital gains extracted.

The chart starts with UK near their colonial peak, with the entire Indian subcontinent under British rule, along with much of accessible Africa. By 2000, the UK had lost almost all colonies. If you were to overlay a 200-year chart of British shipbuilding vs. share of global population under British control, you’d find a near perfect correlation.

“I do find it quite interesting that the UK went from the largest shipbuilding country to not even viewable on the chart by 2000. And that’s while Japan and S Korea rapidly grew. Japan was equally and island nation and S Korea is roughly (a tad smaller I believe) than the UK, so how do you go from the top of the heap to the bottom?”

Important comment, the answer to which was that British shipping companies decided that becoming shipping financiers was more profitable than building ships. This would become the GE illness, where GE decided to become an industrial bank for other manufacturers.

My favourite book on Industrial Policy is ‘How Asia Works’ by Joe Studwell. He compares the Asian Tigers to the Asian non-tigers and distills out what works. I cannot recommend it enough.

typical elite white tower type stuff. completely over looks the big fat Vat tax, that is simply a nationwide tariff, that makes the average person pay the tariff on all purchases, internal and external, instead of the importer.

tariffs alone will not fix the mess bill clinton made with fascist free trade.

ben franklin laid it out plainly when he said american producers must be protected.

the new deal would not have worked without smoot-hawley, and smoot would have not worked without the new deal

industrial policy simply will not work on its own. i bet you will find that china understands this, and their supply chains are loaded with tariffs, duties, quota’s, excise taxes, etc. so to encourage ship building, requires more than just a simple policy.

here is a example of why industrial policy on its own will not work. the onslaught on our supply chains are driving out more and more producers.

https://www.ransonfinancial.com/2023/09/25/baxter-springs-faces-job-losses-as-two-companies-close-their-doors/

Baxter Springs faces job losses as two companies close their doors

September 25th, 2023

In 10 days, National Safety Apparel, formerly known as King Louie, will close its doors in Baxter Springs, leaving over 70 people without jobs. But this isn’t the only blow to the local workforce. Just a few weeks ago, Yellow Corporation, a trucking company, also ceased operations in the same city, resulting in more than 30 people losing their employment. Teresa Humphrey, have been working for NSA for more than 35 years and is among those facing this uncertain future. “It’s sad, makes me want to cry. It’s emotional. I’m scared because I don’t know what to expect. I’m just going to stay here and work as long as I can,” says Humphrey.

————

there is just no way industrial policy can work without protectionism. russia just basically had a gigantic tariff regime enforced from the outside onto them, and the locals are booming.

industrial policy ignores the fact that a great manufacturing economy makes all sorts of things, big things which seems to be what the white tower types are after, but they ignore all of the little things that need to be made that are independent of the big things.

the supply chains that feed the big ticket items, also supply the little guys. so who gets subsidizes and protected to ensure supply chain stability.

and of course, supply chains have supply chains all relying on producers of little things to ensure stability.

when ever i hear a white tower type say efficiency, i say efficient for whom?

Now that Trump’s in maybe it’ll give US Greens time to re-think their pitch, and get into matters deeper.

It seems like there’s layers of stupidity. Real stupid is to try to shut China out of this and that right this minute. Next most stupid is to say hands down China’s ahead and doing the smartest thing possible. But IMO one very smart thing would be for govs not to allow leveraged buyouts. Why? Why is because you get a run of’em, and then whaddya get?? You get what we’ve got.

How long that’s viable should one consider sustainable? Well, the asset strippers might think they’ve got the best game around, but, however China manages to become top producer of whatever, it seems they’ve picked the only course that’ll last any considerable time…time that’s left (unless a Green zeitgeist happened along the way, and companies realized per capita GDP had to be considered). Tremendous exploits just to squeeze out the last capital that’s available, but there it is. I look at things from a casandra’s viewpoint I guess, but also from the viewpoint of keeping sustainable per capita GDP as decent as possible for as long as possible. In time, and in a situation of ultimate progress the extant industries would belch less.

Funny article. The article claims that Chinese did what Japanese and Koreans did before them (paragraph starting with “Second, “). So what is the problem? Japanese and RoK are occupied countries, members of the West and China is independent run by ChiCom? Look at what Biden’s America is doing when it wants to get new industry to start manufacturing in USA. LFP and batteries for cars are good example. There is a company called ICL with production plant in St.Louis, Missoury, which intends to produce LFP and precursors. Total factory investment budget is $450 million and the US government pays 50% of that outright. What is that? Gift? Subsidy? How does Europe behave when Intel or TSMC want to set up a new plant there? “Italy targeting new Intel fab with $4.6 billion incentive bill” published on Supplyframe.com is what comes on top of the page in Google.

Whatever industrial subsidies spent by China are rookie numbers versus the astronomical grift that happens in the American MIC.