By Bruno Baránek, who holds a PhD in Economics from Princeton University, and Vitezslav Titl, an Assistant Professor of Law & Economics at Utrecht University School of Economics. Originally published at VoxEU.

No country is safe from the risks posed by connections between politicians and private companies; scandals involving conflicts of interest plague governments around the world. Using a detailed dataset from the Czech Republic, this column demonstrates that ties between political parties and boards of government contractors lead to overpriced contracts without any corresponding gains in quality for citizens and consumers. The authors also explore how and when increased oversight can mitigate the adverse effects of such connections, informing policy on conflicts of interest in public procurement.

Scandals involving conflicts of interest are prevalent in politics across all countries. For example, during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly a third of the suppliers awarded contracts for personal protective equipment (PPE), such as masks and gloves for healthcare workers, had connections to politicians or senior officials in the UK (Conn and Evans 2020). Similar scandals have occurred in many other countries (for additional examples, see Baranek and Titl 2021). These conflicts of interest raise legitimate concerns about inefficiencies and corrupt practices, leading to reduced competition and innovation, with negative effects on economic growth (Baslandze et al. 2018) and welfare (Varghese et al. 2020). To address these issues, most countries have implemented rules to manage conflicts of interest. The EU, for instance, introduced rules in its 2018 Financial Regulation aimed at preventing the adverse effects of conflicts of interest. Similarly, US law – specifically, 18 US Code § 208 and the Code of Federal Regulations – prohibits officials from taking actions involving entities in which they, their spouses, children, or partners have a financial interest.

The public procurement market is a major channel through which political connections can be exploited. The scale of public resources allocated through these markets is enormous, with public institutions globally awarding contracts worth approximately 12% of GDP annually (Bosio et al. 2022), or about one-third of all government expenditures (OECD 2013). In Baránek and Titl 2024, we examine the additional costs incurred in public procurement due to connections between politicians and companies. Specifically, we trace these links through politicians’ memberships on company boards or direct ownership of companies. When government bodies and companies share ties to the same political party, we observe contract overpricing of approximately 6%. We also explore how and when increased oversight can mitigate the adverse effects of such political connections. By doing so, we aim to inform policymakers how to design rules regarding conflicts of interest in public procurement.

To address these questions, we draw on recent research using a detailed dataset from the Czech Republic that tracks firms’ personal connections to political parties through (supervisory) board memberships and ownership by political candidates. In the Czech Republic, a relatively small proportion of public tender suppliers have personal links to political entities, representing approximately 1% of all suppliers. However, these connected suppliers account for 7% of the total value of public tenders, indicating that they win a disproportionately large share of public procurement contracts. While this disparity is not necessarily problematic, it does raise important concerns. On the one hand, personal connections could facilitate cooperation between firms and government agencies, potentially improving efficiency. On the other hand, and this is a common concern, preferential treatment of connected firms may lead to contracts being awarded to less competitive entities, resulting in inefficiencies. It could also foster increased corruption and create additional bureaucratic hurdles for non-connected firms (Shleifer and Vishny 1993).

Analysing public procurement data from 2006 to 2018, we find that contracts awarded to politically connected firms lead to adverse contract-level outcomes. These contracts are overpriced by approximately 6%, with no corresponding improvement in quality. The dataset encompasses public bodies across all levels of governance, including municipalities, regions, central government, and other government-controlled entities such as state-owned companies. To measure the effect of political connections, we compare contract prices when a firm has an active connection to the party controlling the government entity (i.e. the buyer) with the prices of contracts awarded by the same buyer when the firm had no active connection to the party in power. A firm’s connection changes when politicians to whom the company is linked are either voted out of or elected into office. Over the period studied, 11 elections resulted in approximately 370 changes in supplier connection status, providing a rich dataset for causal analysis. The main findings hold even when the analysis is restricted to close elections, making it difficult to predict in advance which political parties will control the relevant public body. In such cases, the allocation of contracts is effectively random, allowing for a cleaner causal interpretation.

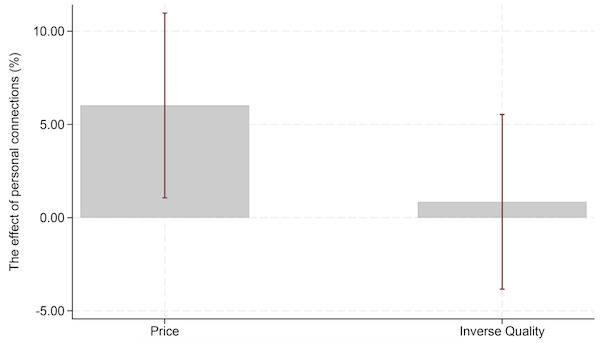

However, even if a contract awarded to a politically connected firm is overpriced, the overall effect on the public sector and general welfare could be positive if the quality of the delivered service is significantly higher. To assess this possibility, we examine whether politically connected firms deliver higher-quality services. Measuring quality is challenging due to the general lack of available data, so we apply a text-analysis-based method proposed by Baránek (2020), which uses contracts’ short descriptions, award dates, and other details to estimate the total lifetime cost of a construction project. This approach allows us to track the number and cost of repairs for the studied construction projects. The findings reveal a small and statistically insignificant negative effect on the quality of projects delivered by connected companies. In the figure below, we illustrate the effects on prices and quality, highlighting the stark contrast between significant price increases and the absence of quality improvements. Note that the quality measure is based on inverse quality, meaning it reflects insignificantly higher lifetime costs.

Figure 1 Impact of a political connection on contract-level price and quality

Note: Price effect measured in relative percentage terms with respect to the baseline engineering estimates; i.e. the figure shows a 6% overpricing above engineering costs. Inverse quality is measured using overall lifetime costs of projects consisting of follow-up repairs of construction projects.

From a policy perspective, it is important to understand how favouritism in public procurement operates. While some procurers may restrict competition or use discretion to favour specific firms (Orlando et al. 2018), the primary channel seems to be the tailoring of project specifications to benefit connected companies. This involves customising technical requirements to make the favoured bidder more competitive. While the misuse of discretion or limiting competition can often be addressed with straightforward policy solutions, the challenge is more complex when favouritism arises from contract tampering. Existing policies target the most obvious issues associated with political ties, such as conflicts of interest, but these regulations only apply when a politician holds a concurrent position in a private firm. They do not cover more subtle connections between political parties and companies. Our research suggests that enhanced monitoring of contract delivery can mitigate the negative impacts of political affiliations, particularly when oversight is conducted by a higher governmental authority over a subordinate one. Given the significance of this finding for policy, and the fact that we cannot definitively establish causality, we recommend that this topic be explored further in future studies.

Here in the US, Jamie Gorelick, comes to mind. She served as deputy attorney general from 1994 to 1997 and is currently a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and Co-Chair of the Homeland Security Advisory Council.

“Jamie G.” also sits on the Board of Directors at Amazon, which has a large presence in government contracting. Her long history with the DOJ certainly can’t hurt if Amazon comes under anti-trust scrutiny for its monopolistic behavior.

And so it goes.

Indeed. After being in the business for a while, you learn to recognize this. The questions will just happen to be written a certain way, and the oddities will just happen to align with the known capabilities of one particular vendor. Often there will be two or three key points where flexibility would unlock a number of competitive options from other bidders, and those ones will be the ones locked in as must-haves with no wiggle room (always with a convincing-sounding business justification, of course). An egregious example would be something like “Must be compatible with [proprietary system that is only supported by vendor X]” but it’s usually more subtle than that.

When you see this, it means the fix is in and you have no chance of success, and you are just being asked to spend a lot of time and effort on an unsuccessful bid in order to give the appearance of a competitive process. Usually the prudent thing to do is decline to bid and move on to something else with a better chance of success.

Tenders regularly attracting only a small number of bidders, or just a single bidder, can be a warning sign that this is going on. If that starts happening a lot, it’s probably time to take a closer look at procurement overall.