Yves here. This post recaps an OECD study of 32 nations on the cost and performance of social programs, as in government funded and even provided measures to support long-term care for the elderly.

This is a very thorny topic that we’ve covered off and on, with the US private long-term care insurance debacle as the focus. The very short version is that in the 1990s, many insurer decided that long-term care was a great new world to conquer. They wrote a bunch of policies with no sound underwriting data. One of their big bad assumptions was on lapse rates, as in how many would pay for policies but drop them later, so that the insurer would get to keep that money and not have to make any payouts. Aside from early deaths, just about everyone who signed up for these long-term care policies paid religously.

A second factor the insurers did not consider was what wound up being adverse selection: those who wound up getting long-term care lived longer on average than assumed by the insurer models, and many experts said this was due in no small measure the fact of them being able to pay for additional care. In other words, the insurers did not allow sufficiently for the policies working as advertised, as in providing for better living conditions and medical minding, would increase longevity and therefor their costs.

Reader ma just send a link to another example of private sector measures in the US not working out according to plan: Americans Risk Losing Life Savings When Retirement Homes Go Bust. Increasingly retirement communities bill themselves as providing full late-in life care, from independent living (usually renting a unit, with communal meals and services like a library, gift shop, ATM, activities, and sometimes outside services on site, like a beauty shop and a clinic) to assisted living (which can be short term after a bad ailment or surgery, or ongoing) to full nursing care. Alzheimers care is not often on the menu due to difficulty and cost.

Most of these facilities require an up front (and sometimes largely refundable to heirs) buy-in. That makes the residents vulnerable to financial loss. From Bloomberg:

Bob Curtis, 87, and his wife Sandy sold their home in Nassau County three years ago and forked over $840,000 to move into The Harborside, a Long Island retirement home that was supposed to provide care for the rest of their lives.

Then the facility went bankrupt and an effort to sell it to new owners was blocked by New York regulators in October. So now, like nearly 200 others who live there, they could see much of their life savings — and their new home – disappear.

Not surprisingly, this article depicts the intensifying long-term care problem as one of longevity, and not also neoliberalism. It used to be that aging adults lived very near their children; their offspring sometime has even moved into the family home when raising their own family. Having the oldster on premises with other adults and sometimes children helping with their care was the preferred route. Now having aged parents move in (save the classic granny apartment over a garage) or an adult child care for a too-often physically removed parent is seen as burden and no longer seems widespread.

By Satoshi Araki, Jacek Barszczewski, Karolin Killmeier and Ana Llena-Nozal. Originally published at VoxEU

Rapid population ageing is increasing the pressure on public finances to provide adequate support for long-term care recipients. This column compares the impact of diverse social protection measures across 32 OECD and EU countries on poverty rates and out-of-pocket expenses among older adults with care needs. The analysis reveals substantial room for improvement and reforms, with existing systems often unaffordable and badly targeted. The promotion of healthy ageing, proactive use of new technologies to elevate care sector productivity, revision of eligibility rules to enable more targeted and inclusive coverage, diversification of funding sources, and optimisation of income-testing are all viable policy options.

Population ageing is accelerating rapidly. Across OECD countries, the share of people aged 65+ has doubled from less than 9% in 1960 to 18% as of 2021 (OECD 2023) and is expected to reach 27% by 2050, increasing demand for long-term care services (Kotschy and Bloom 2022). At the same time, there is growing public pressure to reduce the care burden on families and individuals in favour of government funding and the provision of long-term care (Ilinca and Simmons 2022). Combined with the rising costs of care (OECD 2023), these trends are adding pressure to the fiscal sustainability of public long-term care systems. Ensuring the cross-country comparability of the costs and benefits of public long-term care schemes in 32 OECD and EU countries, 1 a new OECD report compares current long-term care costs across countries and presents evidence on the effectiveness of public expenditures in alleviating the financial burden on care recipients.

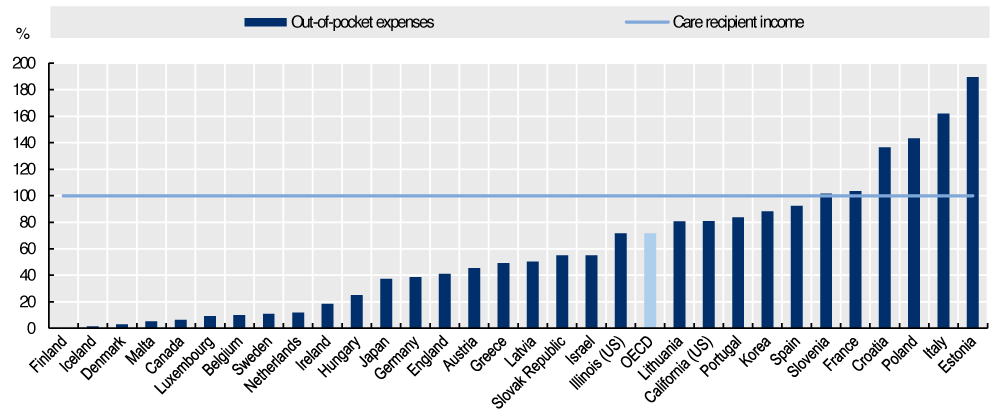

Despite Public Support, Long-Term Care Remains Unaffordable for Many Older People

Without sufficient public support, long-term care services are unaffordable for most older people. The average long-term care cost for individuals with low care needs, already 42% of the median income of older people (without public support), could reach 259% for those with severe care needs. Even though all OECD countries included in the report cover at least part of the cost through benefit schemes, individuals’ out-of-pocket expenses remain substantial, particularly for older people with severe needs (see Figure 1). On average, these costs represent over 70% of the median income of older people across OECD countries, even after accounting for public social protection. However, there is significant variation among the analysed countries. In the Nordic countries such as Finland, Iceland, and Denmark, out-of-pocket costs remain below 5% of median income, while in Italy and Estonia, these costs exceed 150%, effectively pushing older adults into poverty or leaving them with unmet care needs.

Figure 1 Out-of-pocket expenses for long-term care are close to or above the median income in nearly half of countries

Out-of-pocket expenses on long-term care as a share of median income among older people who have severe long-term care needs with median income and no wealth, after receiving public support

Note: Severe needs are defined as requiring 41.25 hours of care per week. Estimates assume older people with long-term care needs would rely on formal home care. Median income refers to the disposable median income of older people (65+) in each country. For readability, data for Czechia, which stands at 482%, are not displayed.

Source: OECD (2024).

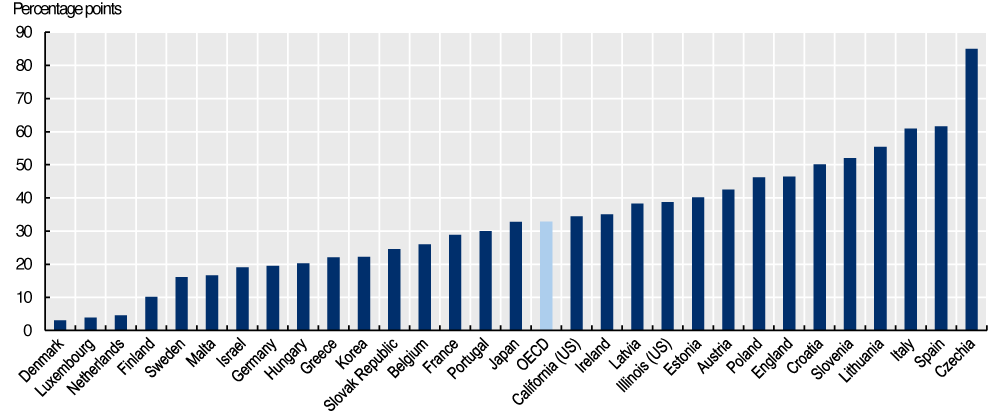

High out-of-pocket expenses for long-term care significantly increase the poverty risk among older people (see Figure 2). On average, poverty rates for older adults with long-term care needs are 31 percentage points higher than for the general older population. The long-term care systems in Scandinavian countries, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands are among the most effective at reducing poverty risks linked to care expenses. In contrast, the poverty risk among long-term care recipients in Italy and Spain is much higher – more than 60 percentage points – in comparison to the total older population (aged 65+).

Figure 2 Older people with long-term care needs face an increased risk of poverty in all countries

Percentage point difference in relative poverty risk between care recipients and all older population (aged 65+), after receiving public social protection

Note: Baseline poverty risk represents the poverty rate among all older people. Estimates are calculated using adjusted survey weights and assume that all older people with long-term care needs would use formal home care. For countries with subnational models, national-level survey data were used to produce the estimates shown. Poverty is defined as having an income 50% below the country’s median income.

Source: OECD (2024).

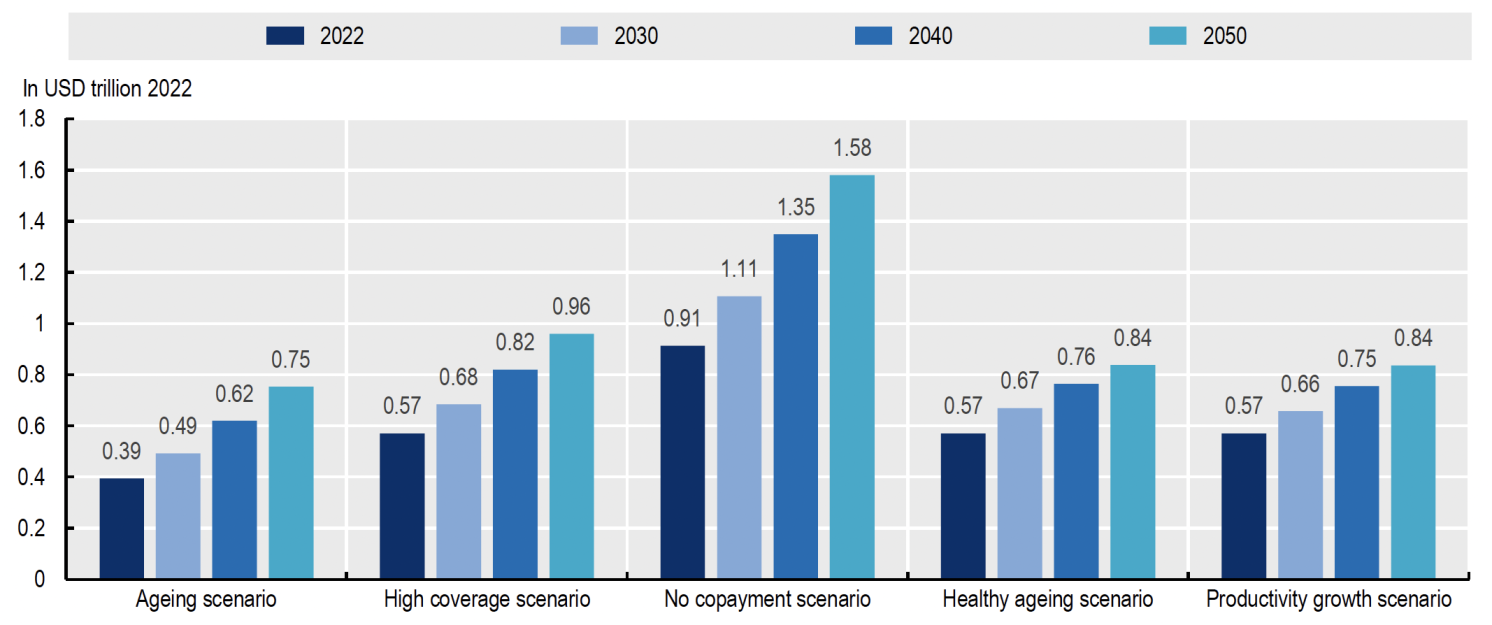

Policy Options to Tackle Growing Demand for Long-Term Care Services

Rising costs, growing demand, and low productivity gains are placing substantial financial pressure on public long-term care systems. The OECD report analyses how this financial pressure could impact future long-term care spending under different scenarios (see Figure 3). In the first scenario (the ‘ageing scenario’) – whereby countries maintain the current level of support and the existing share of older adults with needs receiving long-term care – expenditures are projected to rise by an average of 91% by 2050. In the second scenario (the ‘high coverage scenario’), which assumes an increase to 60% of the share of older adults with care needs, expenditures would increase by 144%. Finally, in the ‘no copayment scenario’, out-of-pocket expenses are fully eliminated and long-term care expenditures grow by more than 300%.

Figure 3 Projections of government spending on long-term care under different scenarios

Sum of all financial protection for long-term care for older people who receive public social protection in trillions of 2022 USD

Note: Bars show the sum of the simulated long-term care spending across 26 OECD and 2 EU non-OECD countries. For countries with subnational models, these are applied to national-level survey data to produce the estimates shown.

Source: OECD (2024).

While population ageing is unavoidable, countries can help older populations adopt healthier lifestyles and introduce preventive measures to reduce dependency and health issues for as long as possible. Programmes like home visits in Scandinavian countries have proven to be cost-effective by increasing the number of active, healthy years (Kronborg et al. 2006). Such policies could reduce future long-term care spending by 13% compared to the baseline high coverage scenario (see healthy ageing scenario, Figure 3).

Although labour productivity growth in the long-term care sector remains low or even negative (OECD 2023), emerging technologies could be put to better use to help reduce overall care costs. OECD simulations suggest that if productivity growth in long-term care reached even half the average productivity growth of the overall economy, long-term care spending by 2050 could be 13% lower than in the baseline high coverage scenario (see productivity growth scenario, Figure 3). New user-centred support tools, such as environmental and wearable sensors, can assist long-term care providers in monitoring, positioning, and recognising physical movements (Bibbò et al. 2022). Virtual carers also play an increasingly important role, supporting both care recipients and providers in managing conditions like diabetes, depression, and heart failure (Bin Sawad et al. 2022).

While taxes are the most common source of long-term care funding, some countries have introduced public long-term care insurance to achieve better risk-sharing and address transparency challenges. For example, Slovenia introduced a long-term care insurance scheme in 2023, aiming to create a more comprehensive system, improve funding transparency, and avoid increasing public-sector debt.

With limited public resources, countries may prioritise supporting individuals most in need: those with low incomes and those with severe long-term care needs. An example of such a policy would be capping out-of-pocket expenses at 60%, 40%, and 20% of care costs for older adults with low, moderate, and severe needs, respectively. Our simulation reveals that such a needs-testing approach could be an attractive option for countries like Latvia, Malta, and Hungary. In these cases, the simulation indicates that this strategy could reduce overall public long-term care spending without significantly increasing the poverty risk among recipients (OECD 2024).

Furthermore, more progressive cost-sharing across the income distribution can help manage long-term care budgets and limit poverty among care recipients. Almost 90% of OECD and EU countries analysed in the report apply some form of income-testing to define levels of support, but individuals with low incomes still face a significantly higher risk of poverty. Optimising income-testing to focus on vulnerable populations can further improve outcomes. In about one-third of the analysed OECD countries, this approach leads to lower long-term care spending and reduces poverty among care recipients, or at least contains spending without increasing poverty rates (OECD 2024).

Conclusion

Achieving fair access to long-term care and the fiscal sustainability of public systems amid population ageing is a challenge for policymakers. The OECD analysis reveals that existing systems are often unaffordable and badly targeted: there is substantial room for improvement and reforms. The promotion of healthy ageing, proactive use of new technologies to elevate the care sector’s productivity, revision of eligibility rules to enable more targeted and inclusive coverage, diversification of funding sources, and optimisation of income-testing are all viable policy options. Each is worth exploring in the search for resilient long-term care systems that can withstand demographic shifts and evolving societal needs.

Editors’ note: This column is a summary of the publication/builds on the publication OECD (2024), “Is Care Affordable for Older People?”.This work, as well as any data and map included herein, should not be reported as representing the views of the OECD, including both its Member countries and its Secretariat. The opinions expressed and arguments employed are those of the authors.

See original post for references

I would like to see the demographics behind all this. If we consider the baby boom as people born between 1945 and 1965 and an average life expectancy of 80 years, then peak demand will be in 2035 and demand will then fall. At this point it would make sense to invest in short-term, ‘peak’, long-term-care capacity.

We are stuck in a ‘cost’ paradigm. Actually, long-term care provides business and job opportunities – an economic benefit as much as a problem.

Who pays? As always there is total myopia about what is money (a state IOU) and how it masks real constraints, ie, resources in the economy – small real-estate footprints, care-givers, food, heat and medications. It costs literally nothing to create public money to support this. Creating private money and extracting the requisite interest overhead is another matter, of course. The issue then comes down to economic tribalism – ‘capitalism’ vs ‘socialism’ and good luck with that.

In summary, it is just another example – if we need any more after housing, education and inequality in general – of the monetization of everything creating the problems we are forced to deal with. Actually, they are not ‘problems’ at all, they are the system working as designed to maximize profit extraction.

Demand might peak sooner if the “smile and do your own risk assessment” public health eugenicists continue to have their way and life expectancies continue to decline.

Or it might backfire if the average age at which people become unable to work goes down even faster.

Your other points are certainly well taken.

The incredible atomization of western societies in full display.

In our household we are three generations under the same roof, taking care of eachother…