Lambert here: Ah, “Accurate information.”

By Daron Acemoglu, Institute Professor in the Department of Economics at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cevat Giray Aksoy, Associate Director of Research in the Office of the Chief Economist at European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), Associate Professor of Economics at King’s College London, Ceren Baysan, Assistant Professor of Economics at University Of Toronto, Carlos Molina, Research Assistant Professor at University Of South Carolina, and Gamze Zeki. Originally published at VoxEU.

Authoritarian regimes often maintain power via cultivating misperceptions about the quality of state institutions and the value of democracy. This leads citizens to underestimate the deterioration of democratic institutions, affecting their voting behaviour. This column presents findings from a study of voters during the May 2023 Turkish presidential elections. Providing accurate information significantly increased support for opposition parties by swaying voters who initially underestimated the deterioration of institutional quality and were leaning towards the incumbent alliance. Addressing misperceptions may lead to greater public demand for democracy, suggesting that accurate information campaigns could help challenge authoritarian narratives.

The Experiments

We use an online experiment and a large-scale field experiment involving 880,000 voters. In both, we provide accurate (research-based) information on the state and implications of democracy and media freedom for mitigating the impact of natural disasters and corruption levels. This information was based on the evolution of Turkish institutions based on V-DEM data and from relevant research on the relationship between democracy and natural disasters (e.g. Besley and Burgess 2002, Cao 2024, Kahn 2005) and media freedom and corruption (e.g. Brunetti and Weder 2003, Ferraz and Finan 2008, Larreguy et al. 2020). These issues were especially salient for Turkish voters following the devastating February 2023 earthquake, which claimed over 50,000 lives and displaced more than a million people. The disaster was worsened by unsafe building practices enabled by local and national corruption (Acemoglu and Tokgoz 2023).

In the field experiment, we implemented two versions of the informational treatment through randomised door-to-door canvassing at the neighbourhood level. This design allowed us to combine the experimental variation with high-quality administrative and electoral data (as in Baysan 2022). The research-based informational treatment presented purely factual information, explaining that declines in media independence increase corruption. The basic informational treatment conveyed information in simpler terms and included more evocative language on democracy, transparency, and corruption.

1

In the online experiment, we included a placebo treatment, as in Acemoglu et al. (2020), which offered encouragement without delivering any substantive information to control for potential experimenter demand effects. We then examined how the research-based informational treatments on media/corruption and democracy/natural disasters influenced voters’ beliefs about democracy and voting intentions relative to the respective placebo treatments.

Voters’ Baseline Views

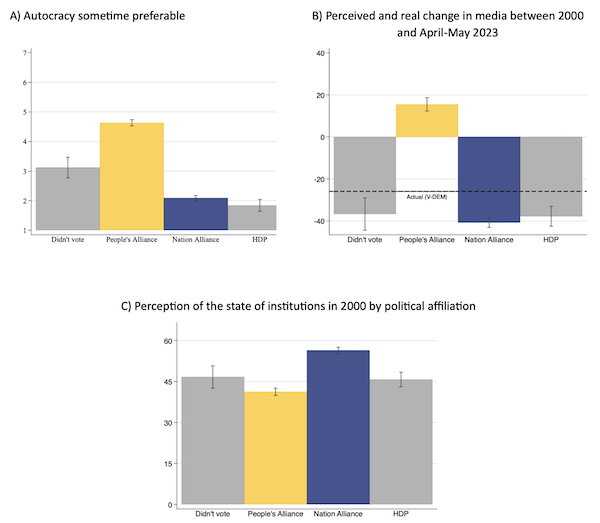

The survey component in our online experiment allows us to measure the baseline views of supporters from different parties regarding their support for democratic institutions, which helps interpret our experimental results. We summarise these findings by focusing on voters from the three main blocs represented in parliament. The incumbent alliance, called the People’s Alliance, included two of the main parties, AKP and MHP, and is shown in yellow in Figure 1. The opposition alliance, the Nation Alliance, includes, most importantly, CHP and İYİ Party, and is shown in dark blue. The People’s Democratic Party (HDP) is shown in grey.

Panel A of Figure 1 shows that participants who voted for the governing coalition in 2018 are significantly more likely to report that autocracy is sometimes preferable to democracy than those who supported the other two coalitions or did not vote in 2018. Panel B presents summary statistics on voters’ perceptions of how media independence has evolved in Türkiye between 2000 and 2022 (the patterns for “democracy” are similar). According to the V-DEM dataset, the actual change is represented by the dashed line. A clear pattern emerges: supporters of the governing coalition have a much more favourable opinion of how media independence has evolved. While these views may partly reflect partisan bias and motivated reasoning, our online experiment is designed to isolate the role of misperceptions. Panel C suggests why there may be different views about the quality of media independence in Türkiye. People’s Alliance supporters were, if anything, more pessimistic about institutional quality compared to the opposition in 2000, before Erdoğan came to power. As Erdoğan’s early reforms expanded religious rights (as well as minority rights, anti-corruption efforts, and EU membership), this could have disproportionately benefited these supporters and shaped their views on institutional evolution over time, potentially driving both their support and misperceptions.

Figure 1 Baseline institutional views by political affiliation

Note: This figure presents the baseline views of participants in the online experiment based on political affiliation (People’s Alliance, Nation Alliance, and HDP supporters). Affiliations are based on self-reported votes in the 2018 election. Panels A and B show the extent to which respondents support authoritarian governments and their perceptions about how media evolved between 2000 and 2023, respectively. The dashed line in Panel B indicates the actual change from the V-DEM data set. Panel C displays voters’ perceptions of democratic institutions in Türkiye in 2000. The bars represent mean scores for each political affiliation. The whiskers show 95 percent confidence intervals.

Main Results from the Online Experiment

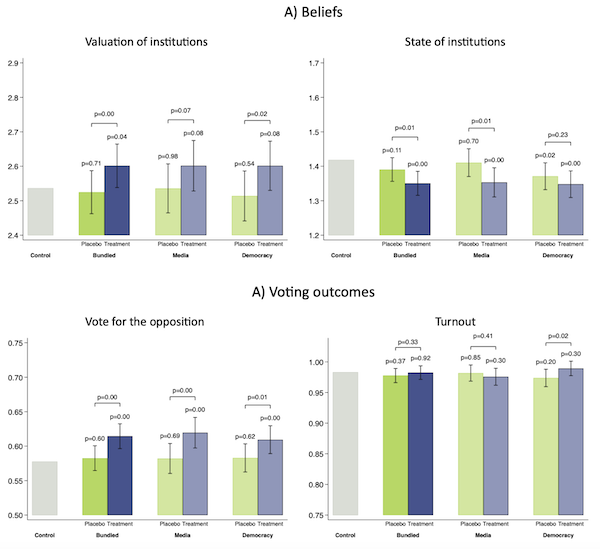

We report the experimental estimates of the informational treatments on voter beliefs. The main results are presented in Panel A of Figure 2. The left panel of Panel A is for the valuation of institutions, which measures the extent to which individuals believe that democratic institutions are important for achieving better outcomes, while the right panel is for the state of institutions which measures perceptions of how democratic institutions have evolved between 2000 and 2023 in Türkiye. Both variables are in standard deviation units.

Figure 2 Treatment effects on beliefs and voting outcomes in the online experiment

Note: This figure summarises the main results from the online experiment. It presents estimates of the informational treatments on voter beliefs in Panel A and self-reported voting intentions in Panel B. Valuation of Institutions measures the extent to which individuals believe that democratic institutions are important for achieving better outcomes, and State of Institutions measures perceptions of how democratic institutions have evolved between 2000 and 2023 in Türkiye. Both variables are in standard deviation units. Vote for the Opposition and Turnout are dummy variables for voter intentions. The difference between the heights of the bars for treatment and control groups gives our baseline estimates of the effect of the informational treatments. The whiskers show 95% confidence intervals, while the p-values on top of the bars are for these differences being statistically different from zero. The p-values at the very top are for the informational treatment being statistically different from the placebo.

We see that informational treatments led to a significant change in the respondents’ beliefs, providing evidence about the importance of misperceptions. Pooling the effect of the democracy and media treatment (the bundled treatment), there is a difference of 6.5% of a standard deviation in the valuation of institutions between the informational treatment and the control groups; this difference is statistically significant at 4%. There is no difference between the control group and the placebo treatment. Moreover, we can comfortably reject that the informational and the placebo treatment effects are equal. When we separate the media and the democracy treatments, the pattern is similar.

The difference between the informational treatment group and the control group regarding institutional valuation is quantitatively sizable, equal to approximately half (58%) of the difference between individuals in our control group who reached tertiary education and those who did not.

On the right, we see a very similar pattern. The informational treatment leads to a decline of 6.8% of one standard deviation in perceived beliefs about how the state of institutions has changed since 2000. The results are also similar when we separate the media and democracy treatments.

Panel B shows the impact of the informational and placebo treatments on the self-reported voting intentions. The bundled treatment increases the probability of voting for the opposition by 3.7 percentage points relative to the control group. The placebo treatment has a minimal and statistically insignificant coefficient, and the gap between the informational and the placebo treatments is substantial, at 3.2 percentage points. The informational treatment effects are statistically significant at less than 1%, and so is the difference between the informational and placebo treatments, as shown in Panel B of Figure 2. We do not find significant effects on self-reported turnout intentions.

Main Results from the Field Experiment

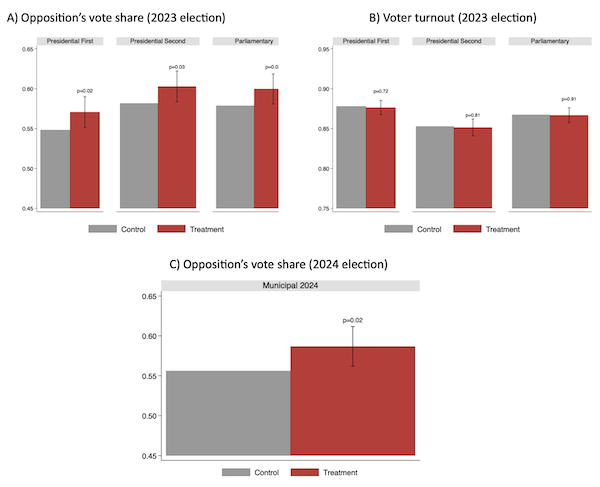

The patterns from our field experiment, shown in Figure 3, are very clear. Analogously with our online experiment results, the informational treatment has a statistically significant and quantitatively substantive effect on opposition vote shares. The bundled treatment increases the opposition’s vote share in the first-round presidential election by 2.4 percentage points (equivalent to a 4.4% increase relative to the control mean). The results, both quantitatively and statistically, are very similar in the second-round presidential election and in the parliamentary election. Panel B shows no impact on voter turnout, which is analogous to the results of voting intention in the online experiment. This implies that the vote share results in Panel A are not driven by mobilising the opposition but by changing incumbent supporters’ minds. Panel C shows a statistically significant positive effect on the opposition’s vote share in the 2024 municipal elections, almost a year after our experiment. This raises the possibility that accurate information may have swayed some voters sufficiently to alter their long-term allegiances and voting patterns.

Figure 3 Treatment effects on voting outcomes in the field experiment

Note: This figure summarises the main results from the field experiment. It presents ballot box-level estimates of the treatment effects on the opposition’s vote share and turnout in the 2023 first and second round presidential, and parliamentary elections in Panels A and B, and the opposition’s vote share in the 2024 municipal election in Panel C. In this figure, we focus on the bundled treatment, a dummy variable for the research-based informational or the basic informational treatment at the neighbourhood level. The difference between the heights of the bars for treatment and control groups gives our baseline estimates of the effect of the informational treatments. We include the number of registered voters at each ballot box in 2023, ballot-box geographic controls (population density, precipitation, temperature, ruggedness, distance to Istanbul, and distance to the coast), neighbourhood-level controls from the 2018 election (opposition’s vote share, turnout, and number of registered voters), as well as dummies for different regions and strata fixed effects. The whiskers show 95% confidence intervals, while the p-values on top of the bars are for these differences being statistically different from zero. Standard errors are clustered at the neighbourhood level.

Mechanisms

Our main results appear to be driven by participants and voters who initially underestimated the deterioration of institutional quality and were leaning towards the incumbent alliance. In the online experiment, we find that participants with more misperceived beliefs adjust their perceptions of democratic institutions after receiving accurate information and are more likely to shift their voting intentions toward the opposition. In contrast, the placebo treatment shows no significant effect on these outcomes.

In the field experiment, neighbourhoods with lower opposition vote shares in the 2018 parliamentary election – historically supportive of the governing coalition – show much larger effects from the informational treatment across all three 2023 elections. In contrast, neighbourhoods with higher 2018 opposition vote shares show smaller and statistically insignificant effects.

These results lead to two key points. First, a substantial portion of government supporters view the informational treatments as credible. Second, the treatments have a greater impact on those with more misperceptions about the state of democratic institutions in Türkiye or their effectiveness in delivering desired outcomes.

Conclusion

Authoritarian regimes that remain in power for extended periods can diminish public demand for democracy and media freedom.

Our findings offer a positive interpretation against this concern: at least part of the support for authoritarian regimes is coming from misperceptions about their institutions and policies rather than a lack of actual demand for democracy, and may be more malleable than typically presumed. Unlike in other studies (e.g. Adena et al. 2015, Enikolopov et al. 2023, Peisakhin and Rozenas 2018) where new information about a party’s performance can deepen polarisation, including in a similar context as ours (Baysan 2022), we do not observe this effect in either the online or field experiments. The fact that our treatments were based on factual and research-based information designed to correct misperceptions and were, to the extent possible, presented in a non–partisan manner may have been important in communicating with government supporters and with people with different baseline beliefs. This suggests that such interventions, based on impartial, accurate information, have the potential to break self-fulfilling traps where authoritarian governments convince their voters that democracy is not for them.

I wonder why our National Endowment for Democracy is not already supplying the Turkish people with all the “accurate information” they need?

And the very next thing I see is this, suggesting Americans were willing to trade effectiveness for trustworthiness when they voted for Trump.

https://thehill.com/opinion/campaign/5040497-voters-prioritize-government-effectiveness/

I guess the Turks aren’t the only ones who need a bigger dose of “accurate information.”

So propaganda works?

I await the next breathtaking research conclusion from these presumably no so young Turks. Perhaps these economic brain geniuses will find that money can be used to pay for things, even bogus research.

“Authoritarian regimes that remain in power for extended periods can diminish public demand for democracy and media freedom.”

Very evident in the US and EU…

This guy Acemoglu wrote “Why Nations Fail”, which I read in an undergrad econ class many years ago, and which I remember being amazed by at the time. I thought he and his co-author Robinson had explained history.

I need to re-read that book now that my worldview has changed dramatically, and with the benefit of more than a decade of hindsight.

Side note – Acenoglu and Robinson apparently won the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics.

Him winning that “Nobel” tells me that his work is plute-fellating trash.

https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/xi-jinping-china-economy-rotting-from-the-head-by-daron-acemoglu-2022-10

October 28, 2022

China’s Economy Is Rotting from the Head

By Daron Acemoglu

[ The thrust of the development research was always prejudicial, so that social organization in any other country must imitate that in America, or development of any other country would be undermined. China of course was a problem, but that problem would disappear as China became America. The problem is that China have not become America but is still developing and Daron Acemoglu finds this intolerable.

For me, this is what prejudice is all about. Prejudice that affords an excuse for advanced countries to try to undermine development in countries found to be disagreeable. After all, China has sought to introduce a resolution in the UN to affirm a national right to development but America has prevented this.

I find the work of Acemoglu, as the essay attacking President Xi, shamefully prejudiced. ]

They seem a little hazy as to the precise nature of this “accurate” information with which they “treat” their subjects.

They seem a little hazy as to the precise nature of this “accurate” information with which they “treat” their subjects.

[ This is an intriguing comment, to begin with. Please explain further when possible. ]

All I see see is that they move people’s opinions by providing a menu of unspecified information that they claim (but don’t demonstrate) is supposedly accurate. Absent any ability to verify the accuracy of such information, since they can’t be troubled to directly tell us what it even is, all I’m able to see here is that if you present people with a basket of acts supposedly leading to a given conclusion, you can at least temporarily affect how they evaluate things.

Which I would think everybody already knew.

This is really helpful to me in organizing thoughts:

“All I see see is that they move people’s opinions by providing a menu of unspecified information that they claim (but don’t demonstrate) is supposedly accurate…”

Models that are suppositions, but never verified or set aside when there is no verification. Brad DeLong offered just this complaint about development models (about the Washington Consensus in particular * ), then DeLong turned away from development economics.

* https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Washington_Consensus

The problem with expts like this is that the treatments are usually too canned (and I’m still not sure what exactly the treatment was in this case.)

In the most dangerous cases, the Huey Long rule applies: fascism often comes in guise of anti-fascism or, worse, “democracy.” You don’t want to ask respondents if they prefer “democracy” or “autocracy.” You want to ask people if they support suspending basic rights for people who they don’t like, cancelling elections if their opponents win, and so forth. Especially in a society sufficiently socialized to “western norms,” very few people are openly in favor of “autocracy,” and worse, they don’t believe that they are. Instead, they are in favor of a “democracy” that behaves autocratically, all the better to “defend democracy.”

Someone should really run an expt like this (alas, not in academia now…)

“democracy” is a flag-word loaded with a symbolic charge. A word and the concept or reality that the word carries in its definition are different things. European populations have been soaked for a century in a surrounding speech maintaining a belief (that’s the key concept) of parliamentary multi-parties regimes being of the category “good”. This belief is key for the regimes in order to keep ruled populations quiet. In other words, the term “democracy” has a religious-like function for social consent.

The belief is currently degrading somewhat inside the framework of European Union, because in order to keep going EU superstructure and particular countries regimes are now acting in very authoritarian ways (like the recent short-cutting of elections results in France, pure cancellation in Romania, and long before this since 2005, referendums results being ignored) and aggressive war-mongering ways in foreign policies (regime change wars inflicted left and right), deals with clear tyrannies and even sectarian terrorist groups like current Syrian rulers. EU is behaving like British Empire in the 19th c. And this is very visible because internet.

the case of USA is much more obvious because the way the country began. When I was teenager in the 70’s in Europe,in History classes, there were the lessons about the way colonial monarchies evolved: Nouvelle-France, New England, Nueva España. The case of New England becoming USA was a joke. We would tell the teacher: so they made a democracy, they say, that did apply only to white anglo-germanic calvinist-lutheran people??? and their funny so-called “founding fathers” for who they have some kind of religious cult, were themselves practicing slavery. ROTFL. The fact their constitution had to be corrected over time tells it was non-consistent in the first place, otherwise it would not have required corrections. The contrary of a concept.

USA is just a Roman-like patrician republic, ie. an oligarchic clans regime.

It means it is an authoritarian regime since day one to now.

There were many “ironic” episodes in the evolution of post-monarchic regimes in the Americas.

For instance when Mexico was founded, the concept of citizenship was real ie. it was not racialist. It was the case in monarchy time already: on paper all Mexicans were subjects of the crown of Spain.

When Mexico became independent the transition to concept of democracy was then easy and full.

In Northern Mexico, because very low demographics, it was proposed to Americans to settle as farmers in exchange for free land. Of course the settlers had to follow Mexican law. They didn’t. Among other things, as they were mostly from farming USA South, they kept their slaves, which did break the law because slavery was illegal in Mexico. Well they also refused to pay tax and refused to trade with the rest of the Mexican economy but established a black trade with Louisiana and rest of USA. Finally they just seized the whole state of Texas. Democracy at work….

Most Americans seem to have a warped understanding of democracy. They have been conditioned by the corporate/oligarch owned media to believe that having corporate/oligarchs choose the candidates, we are allowed to vote for, long before there has been one vote cast, somehow qualifies as a ‘government elected by the people.’