Yves here. AirBnB is very much a class warfare issue. In cities with chronically tight rental markets, like New York City and San Francisco, there are investors who have purchased apartments solely for the purpose of leasing them on a short-term basis, and thus reducing the supply available to residents. Some AirBnB landlords contend they need the additional income to be able to hang on to the property as a primary residence. It seems likely that AirBnB has rounded up as many of this type of lessor as possible to put a good face on its end-run of hotel regulations, much the same way large banks round up community banks to lobby for breaks that benefit the big fish too.

Some may contend that home owners should have the right to as they see fit on their properties. But that is a false view. Living in a community and enjoying its services (police and fire department protection, garbage collection, ability to enroll children in public schools, and frankly enjoying its zoning rules, designed to preserve the value of local real estate) also entails obligations, and that includes adhering to community positions on transients. The last community I lived in completely barred rentals of less than 30 days. Other rules included outlawing the removal of trees over a certain size without hiring a professional arborist and extensive business licensing requirements.

As the article notes, one constituency opposing re-liberalization of AirBnB rules in New York City is hotel workers (and clearly owners). In other areas of the US, AirBnB rentals are falling out of favor due to gotcha high cleaning charges. But NYC is such a chronically expensive city for hotels that AirBnB is apparently still competitive.

By Samantha Maldonado, a senior reporter for THE CITY, where she covers climate, resiliency, housing and development. Published Dec. 9, 2024 by THE CITY

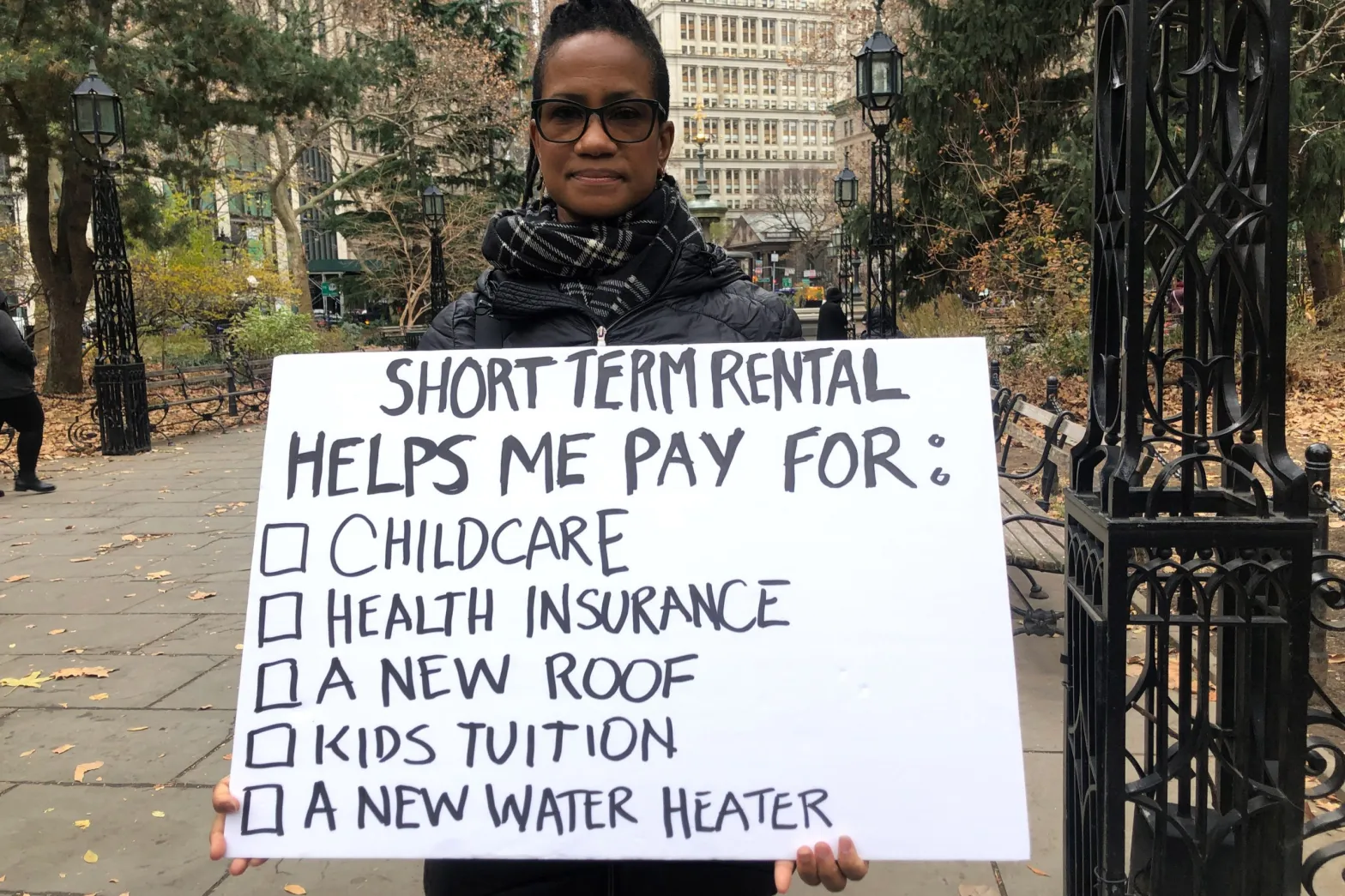

Pro and anti-Airbnb demonstrators clashed in City Hall Park after a bill was introduced in the City Council to make it easier for some homeowners to provide short-term rentals, Dec. 9, 2024. Credit: Samantha Maldonado/THE CITY

Pro and anti-Airbnb demonstrators clashed in City Hall Park after a bill was introduced in the City Council to make it easier for some homeowners to provide short-term rentals, Dec. 9, 2024. Credit: Samantha Maldonado/THE CITY

Rival rallies over proposed relief of restrictions on Airbnb and other short-term rental platforms faced off at City Hall Park Monday, playing out a live debate in front of the home of the City Council that will ultimately have to pick a side.

On one side was the newly launched “Tenants not Tourists” Coalition, made up of groups that included the Crown Heights Tenants Union, Tenants PAC and Make the Road New York, along with the Hotel and Gaming Trades Council. They were there to protest a City Council bill introduced last month that would allow owners of one- and two-family homes to use their properties as short-term rentals.

On the other side, homeowners, many former Airbnb hosts, held signs in support of the bill. They said that short-term rentals allowed them to afford rising expenses for maintaining their properties and gave them power and stability.

Chants that started with the tenant and union demonstrators echoed into call-and-response-style interactions between opposing sides.

Tenant-rights advocates and hotel union members rally at City Hall Park against a bill that would make it easier for some homeowners to have short-term rentals like Airbnb, Dec. 9, 2024. Credit: Samantha Maldonado/THE CITY

Tenant-rights advocates and hotel union members rally at City Hall Park against a bill that would make it easier for some homeowners to have short-term rentals like Airbnb, Dec. 9, 2024. Credit: Samantha Maldonado/THE CITY

“Housing is a human right!” the tenants and hotel group chanted.

“We agree with you!” came shouts from the other side.

“People over profit!” the tenants and union members chanted.

“Are we not people?” came the response from the homeowners’ side.

Members of each side had argumentative standoffs with their counterparts.

“It’s a little intense right now,” said Whitney Hu, director of civic engagement for Churches United for Fair Housing, addressing the crowd after having a heated one-on-one conversation with a homeowner. “We’re all mad, we’re all frustrated. Those in power have not seen our pain. They haven’t seen our grief. They haven’t seen that some of us have made really, really hard decisions.”

“I can agree with that,” said Mo Oliver, a Bedford-Stuyvesant homeowner who had been speaking with Hu. He said he had paid his bills by Airbnbing his home after losing his job during the pandemic.

“At the end of the day, all we want, I think all of us can agree, is a New York City that centers us, a New York City where we can wake up, pay the bills, send our kids to school, pay rent on time, pay our mortgages on time,” Hu said. “The people we are fighting are the ones who have the money.”

Murmurs throughout the crowd revealed differences in who attendees thought the moneyed interests were: companies like Airbnb or the hotel lobby.

Revisiting Restrictions

Starting in 2023, New York City Local Law 18 has barred property owners from renting out a whole house or apartment to guests for fewer than 30 days. After registering with the Mayor’s Office of Special Enforcement, they may only rent to up to two guests sharing their space, such as in an extra bedroom.

The new law got rid of thousands of short-term rentals across the boroughs — a 92% drop, according to a studycommissioned by Airbnb.

Sunset Park homeowner Gia Sharp rallied in City Hall Park in favor of allowing short-term rentals like Airbnb, Dec. 9, 2024. Credit: Samantha Maldonado/THE CITY

Sunset Park homeowner Gia Sharp rallied in City Hall Park in favor of allowing short-term rentals like Airbnb, Dec. 9, 2024. Credit: Samantha Maldonado/THE CITY

Councilmember Farah Louis’ bill, Intro. 1107, would allow for rentals of less than 30 days in one- and two-family houses, increasing the number of guests allowed to stay from two to four adults, plus their children. Under the bill, the primary occupants would not need to be present during the guests’ stay, so they could rent space while on vacation, but would still need to register with the city. The hosts may also install locks internally to restrict guests from certain rooms, closets or drawers.

For many, short-term rental income has become a vital resource to help cover these escalating mortgage costs,” Louis (D-Brooklyn) said at a November Council meeting. “These homeowners pursuing the American dream are being held back by a policy that treats them as if they are commercial enterprises.”

Airbnb, which has spent over a million dollars this year on local lobbying, said the 2023 law didn’t do much to alleviate the housing crisis or expense of renting in New York City, while helping fuel a spike in hotel prices.

“This bill aims to fix an overly restrictive short-term rental law that, in the last year, has failed to decrease rents in NYC and only increased hotel rates exorbitantly for travelers,” said Nathan Rothman, Airbnb’s director of policy, in a statement. “It’s time to fix a broken law that hasn’t helped housing but has padded hotel industry pockets at everyone else’s expense.”

In an email, Vijay Dandapani, president and CEO of the Hotel Association of New York City, called the claim that the short-term rental restriction law resulted in higher hotel rates is “a fiction peddled actively by Airbnb.” He added that hotel rates, adjusted for inflation, did not recover to 2019 levels until September, and government action to enable more youth hostels could give tourists more affordable options.

The tenants and hotel unions said Airbnb restrictions put more housing stock on the rental market for long-term New York tenants — essential given the city’s housing shortage. The restrictions on short-term rentals were thought to be a boon for hotels, which competed with them.

Many homeowners, on the other hand, said they longed for the flexibility and income of renting an extra apartment in their rowhomes. They were able to host family members as well as visitors, but with the ban, their income streams petered out.

Of course, some property owners still advertise stays for less than 30 days on websites like Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace.

And to be sure, some former Airbnb hosts turned their former short-term rentals into long-term housing for locals. Streeteasy listed many apartments with descriptions specifying they used to be Airbnbs, or the owners had planned them to be.

Gia Sharp, a consultant and co-founder of the group Restore Homeowner Autonomy and Rights, or RHOAR, switched to hosting long-term guests — those who stay for over 30 days — in her two-family Sunset Park home after the law restricting short-terms went into effect.

She liked short-term stays so she could rent out her extra unit when she didn’t have family staying with her from out of town, and the extra income helped with maintenance expenses.

Sharp said she was open to conversations about amending the bill so that it would specify properties must be owner-occupied in order to have short-term guests — discouraging companies from buying up housing to rent it out to travelers.

“Local Law 18 is good for the majority, but it went too far,” Sharp said. “I think that tenants’ rights are completely valid, and we’re on the same side. We want housing affordability, but we’ve been pitted against each other, and it’s a divide and conquer narrative that we’re not here for. But we want to make sure that everyone understands what this bill really does: it’s really helping homeowners, helping New Yorkers.”

But Darius Khalil Gordon, executive director of the tenant group Met Council on Housing, said he was opposed to any legislation that might create an opening for predatory practices.

“Airbnbs and corporations like Airbnb will actually use this as a guise for one-and two-family houses,” he said, “but they know they’re gonna come in, buy all these apartments, jack up the rent, jack up whatever it is, and just make profit.”

“Airbnb is very much a class warfare issue.” — Airbnb (there are plenty of similar sites like Booking and VRBO) is popular worldwide, but for reasons of economics and convenience. Class warfare has nothing to do with it.

I’m reluctant to wade into these discussions about Airbnb et al, because real estate (like politics) is usually a local affair. What makes sense in NYC or SFO doesn’t necessarily make sense elsewhere. A very informative site (insideairbnb.com) has detailed statistics on Airbnb’s local presence around the world. Skip its narratives (which are foaming-at-the-mouth anti-Airbnb) and go directly to the underlying data, and you can see that many Airbnb units really are owned individually; hence, the argument that lots of Airbnb owners are just renting out their premises for pin money is true. E.g., even in NYC, 49.8% of Airbnb properties are single listings:

https://insideairbnb.com/

This particular article on NYC skims over the fact that NYC hotels are way too expensive. Airbnb’s popularity took off because hotels cost too much; if hotels had simply lowered their prices and provided what many visitors actually want (a bed+bath that is clean, safe, convenient, and reasonably priced) as opposed to what hotels think they want (i.e., all the other bells and whistles: 24-hour room service, conference center, fitness center, restaurant, bar, concierge, security, parking, valet, daily maid service, minibar, evening turndown service with a silly bonbon on your bedsheets, etc.), they could have long ago wiped the floor with the likes of Airbnb. The founders of Airbnb certainly did not set out to make it hard for NYC residents to find a place to live; this problem should be addressed, but it’s a side effect of Airbnb’s remarkable success…..which itself is largely a result of the hotel’s industry’s greed.

Going local: here in Italy, there’s a lively ongoing debate about putting restrictions on short-term rentals (as usual, Airbnb attracts the most wrath). Florence (the biggest city in Tuscany) has recently placed restrictions on short-term rentals, supposedly to alleviate a shortage of long-term rental units. But the debate has been fierce (and continues), because the local government itself understands that Florence simply does not have enough hotels to cope with the flood of visiting tourists (and too many of these hotels offer Fawlty Towers service at a ridiculous price). The Florence government (and the tourism lobby) would like to encourage overnighting tourists while discouraging day tourists (the former spend way more money than the latter), but banning the likes of Airbnb will have exactly the opposite effect. As for the shortage of affordable long-term rentals in Florence, this has many causes: restrictive building codes, high construction costs, the city’s popularity with wealthy foreigners (who buy apartments in the city center as a pied-a-terre for their occasional visits, leaving them unoccupied for most of the year), etc. The Airbnb effect is real and needs to be addressed, but so do these other factors. I doubt that a ban on short-term rentals will lead to the snazzy apartments in central Florence listed on Airbnb being made available (i.e., affordable) to working-class Florentines or students or immigrants. A competent local government (magari!) might use tourism revenue to build subsidized housing and student dormitories, but that would require hard work and active governance; performance art and speechifying is much easier (and something at which Italian politicians excel), hence they announce a few restrictions on Airbnb (et al) and it’s kudos and glasses of prosecco all around. Meanwhile, Florence continues to have a housing shortage, hordes of tourists, and bad hotels. Nothing changes.

There is also the taxation angle: Airbnb is a non-cash operation and is quite fussy about its tax reporting, hence it is near-impossible to rent out one’s Italian property on Airbnb and avoid the taxman. Banning Airbnb will likely drive many of these short-term property rentals to other sites that allow owners to take payment in cash, thereby costing the government tax revenue while doing nothing to solve the problems at hand. I have no idea what the tax situation is in NYC, but human nature being what it is, I would imagine that restricting short-term rentals will simply drive many properties back into the un-taxed cash economy.

Local governments everywhere are going to have to come to terms with the rise of online non-hotel booking services (Airbnb and the many others), because they are here to stay. I don’t have a one-size-fits-all answer to this situation (probably none exists), but I don’t see that putting arbitrary restrictions on legal commerce is a viable solution.

Manhattan is not that expensive to stay in. I can find rooms a month ahead of time right now for under 200 a night easily. You just need to plan ahead.

And cities put arbitrary restrictions on availability of housing all the time. It’s called zoning.

Re: “Gia Sharp..” and “…her two-family Sunset Park home…“, who “…liked short-term stays so she could rent out her extra unit when she didn’t have family staying with her from out of town“.

It would be mildly interesting to know how much of the use is AirBnB and how much is family staying there. In any event, she’s got a rentable unit that is off the market for long-term rental tenants, thus she is a contributor to NYC’s housing shortage.

And yes, NY hotels are expensive (just like Florence, London, Paris, and the other major cities that people want to visit). For New York, this is partly due to the taxes: NYC sales tax (8.875%) + Occupancy Tax (5.875%) + Unit Occupancy Tax ($2/night) + Javits Occupancy Tax ($1.50/night). And there’s a shortage of rooms, as some of the more historically affordable hotels (e.g., those on Lexington Ave in the 40s and low 50s) remain closed ‘post-pandemic’, or have been converted to other uses.

I don’t understand what the pro-Airbnb people are protesting here. They claim to need the extra rental income to pay for upkeep on their properties and to pay their bills, but the law as it currently stands sounds like it allows exactly that – people who live in their own homes and have extra rooms can rent them out for less than 30 days. So what is the problem?

According the the article, NYC bans whole houses and apartments from being rented short term, and they should – that’s what causes problems. We had one woman buy up a whole row of residential houses in our town and rent them out short term. According to her, it was one house to put each of her kids through college. At the expense of everybody else who might want to live in the neighborhood affordably. Unfortunately for her, she was rather extravagant with her rentals – they had firepits on the roof deck(!), allowed loud parties, and did other things to attract neighbors’ attention, which eventually led to them being the poster children for why whole house short term rentals needed to be banned, and they were.

Sounds to me like the pro-short term protestors in NYC are wannabe squillionaires who are useful idiots for Airbnb and are not arguing in good faith.

Since Airbnb got big in the first place by ignoring local laws, not only should short term Airbnb rentals be banned, but in a just and fair society, the company’s charter would be revoked and executives would face consequences to pay for flouting the laws. Airbnb needs to be killed with fire, like the rest of the destabilizing bad ideas coming out of Silicon valley from our would-be tech overlords.

We need a federal override of zoning decisions in the twenty (or so) most important metros. NYC, Los Angeles, SF, etc., all should have multiples of the available housing stock and the ability of local home owners to stop development is completely unacceptable.

I think this is a terrible and very dangerous idea. If we’re going to have private ownership of property by anyone but the billionaires, there has to be a balance between local interests and the broader public interest. Too often, developers serve neither — only themselves. And they do it with OPM (other people’s money, often public dollars).

I do not propose a libertarian wild west. The Renovation of Paris was not driven by local real estate speculators but through the vision of central government. Most large American cities require a renovation. Local real estate Lords, or SFH owners, should not be able to control the supply of housing, and access to shorter commutes and good jobs, for the entire country. I prefer that class, as a class, be smashed by the state.

I don’t see any sign that we have a central government that would or could do this. And if we did, I’d go for single-payer health insurance first. As it stands, we won’t get either in my lifetime nor my daughter’s. Maybe in your grandchildren’s? (That the world will be here for anyone’s grandchildren seems a wide-open question at this point.)

The Supply Side YIMBY argument is based on a false premise. There is plenty of housing stock available, it is just overpriced or held off the market by landlords who will not lower their expectations of revenue. A public good requires a public solution – intervention in the market to rectify unequal positions between tenants and landlords (including maintenance and security requirements) and massive construction of reasonably priced public housing.

With the current monoparty brain geniuses running the joint, I think the only way any of that will happen is by tenants organizing themselves and using the leverage they have over the landlords.

No, there is not plenty of housing stock available. Nor is the vast majority of the available existing housing stock appropriate for families. Local interests and the existing Federal regime have screwed up housing everywhere and the table needs to be flipped.