Yves here. This post provides some useful analysis of US programs that encourage or mandate the Federal purchase of domestic goods. It also considers the employment impact. However, it skips over knock-on questions, such as whether increasing purchases of American goods is too unfocused to do much good in terms of competence and competitiveness, as in this policy is not terribly beneficial in the absence of industrial policy.

Needless to say, this piece highlights a problem for Trump’s DOGE program. Logically, a cost-fixated initiative should demand that US agencies buy the lowest cost products. But that conflicts with his imperative of trying to punish strategic competitors, most of all China, by lowering our trade surplus with them.

By Matilde Bombardini, Andres Gonzalez-Lira, Bingjing, and Li Chiara Motta. Originally published at VoxEU

‘Buy national’ provisions serve as non-tariff barriers to trade and are often defended as tools for job creation and industrial policy. This column examines the costs and benefits of current and anticipated future provisions under the Buy American Act of 1933, which discourages federal agencies from purchasing ‘foreign’ goods. Forged during the Great Depression, the Act continues to guide federal procurement in the US, and has been revised under both Democratic and Republican administrations. The findings indicate that while these policies may increase domestic employment, they come with rising welfare costs.

The ongoing policy debate over rising protectionism and stricter trade restrictions has sparked widespread dialogue among economists. Although recent studies have brought attention to the costs associated with tariffs (Fajgelbaum et al. 2020), evidence regarding the impact of non-tariff barriers remains limited (Conconi et al. 2016, Kinzius et al. 2019). One measure is the adoption of ‘buy national’ provisions in public procurement, which mandate that goods acquired by the federal government meet regional sourcing or manufacturing requirements.

These provisions, which serve as barriers to the import of goods, create welfare costs by reducing import shares compared to free trade conditions. When buy national clauses mandate that the government purchase higher-cost domestic goods, the resulting expenses are borne by taxpayers. However, proponents argue that sourcing goods domestically helps promote job creation and retention, prompting the question: what is the ultimate welfare cost of these policies?

In Bombardini et al. (2024), we address these questions by examining one of the longest-standing and most prominent examples of domestic content restrictions in public procurement: the US Buy American Act of 1933 (BAA). The BAA set a precedent by requiring federal agencies to prioritise “domestic end products” and “domestic construction materials” for contracts performed within the US that exceed the micro-purchase threshold, typically set at $3,500. The two key elements of the BAA are the requirements that, unless specific waiver conditions are met: (1) goods purchased by the US federal government must be manufactured in the US, and (2) at least 50% of the cost of components must be spent on US-produced inputs.

Forged during the Great Depression, the BAA has become a renewed source of debate for several reasons. First, the landscape of globalisation has changed significantly since its inception, characterised by substantial growth in trade volume and a shift in composition. Today, two-thirds of global trade comprises intermediate goods (Johnson and Noguera 2012, Antràs and Chor 2022), which influences the BAA’s impact. Additionally, the BAA laid the groundwork for various domestic-content mandates, such as the Federal Highway Administration’s “Buy America” policy and the “Build America, Buy America” provision in the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. Finally, the BAA has been subject to reforms under both the Trump and Biden administrations: the most significant changes in nearly 70 years are set to make the BAA increasingly restrictive by 2029. This change guides one of our counterfactuals.

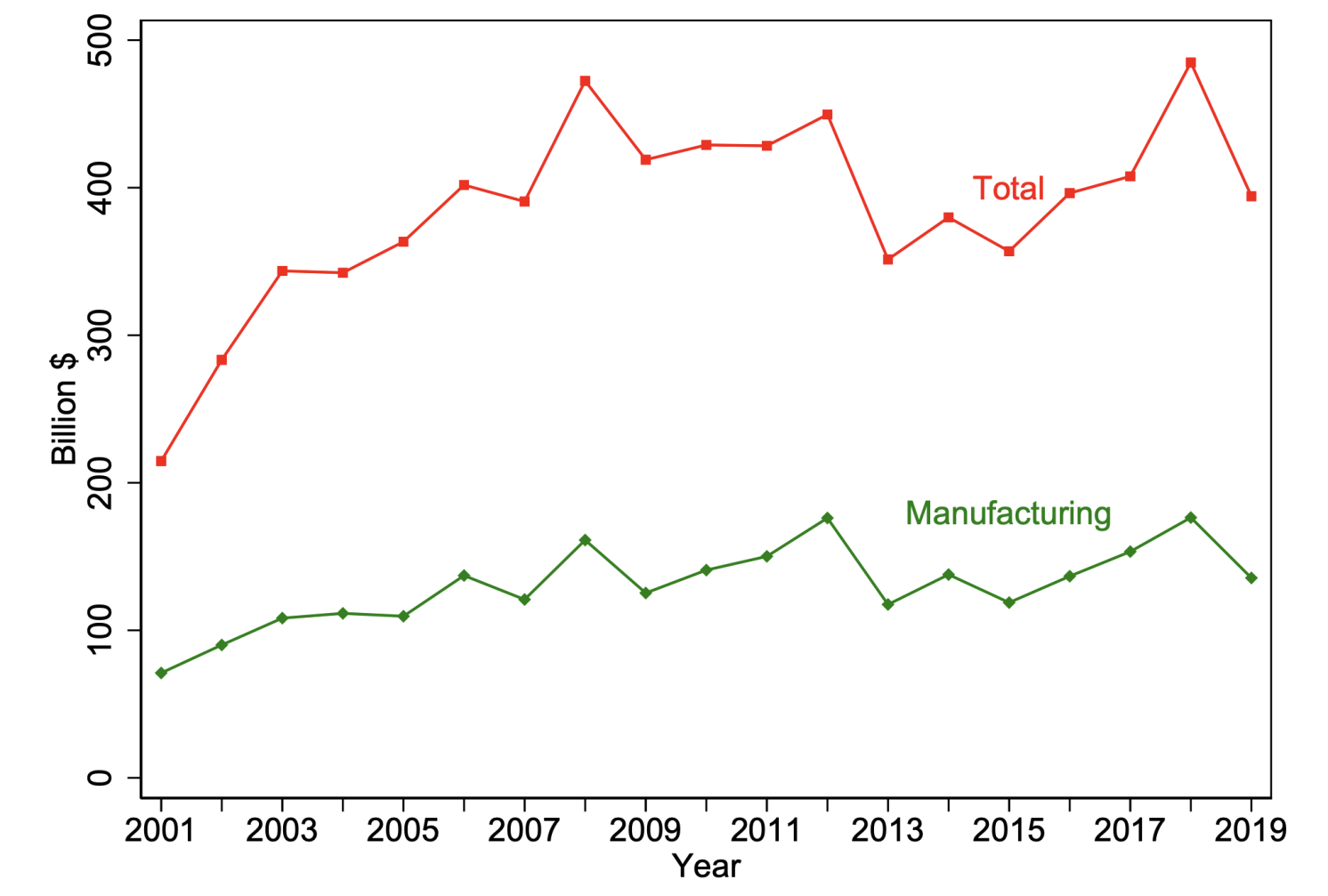

In our analysis, we leverage micro-data from the Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) covering all federal procurement contracts from 2001 to 2019. This comprehensive dataset provides insights into contract values, product/service sector codes, and the geographic locations of both purchasing agencies and producing firms (including their domestic or foreign status). Figure 1 shows trends in annual procurement spending, with the red line representing total spending across all categories and the green line focusing on manufacturing contracts. Between 2001 and 2008, procurement spending doubled and then stabilised at approximately $400 billion annually. Manufacturing industries make up about one-third of this spending and encompass various sectors.

Figure 1 Federal procurement spending, total and manufacturing only, 2021–2019

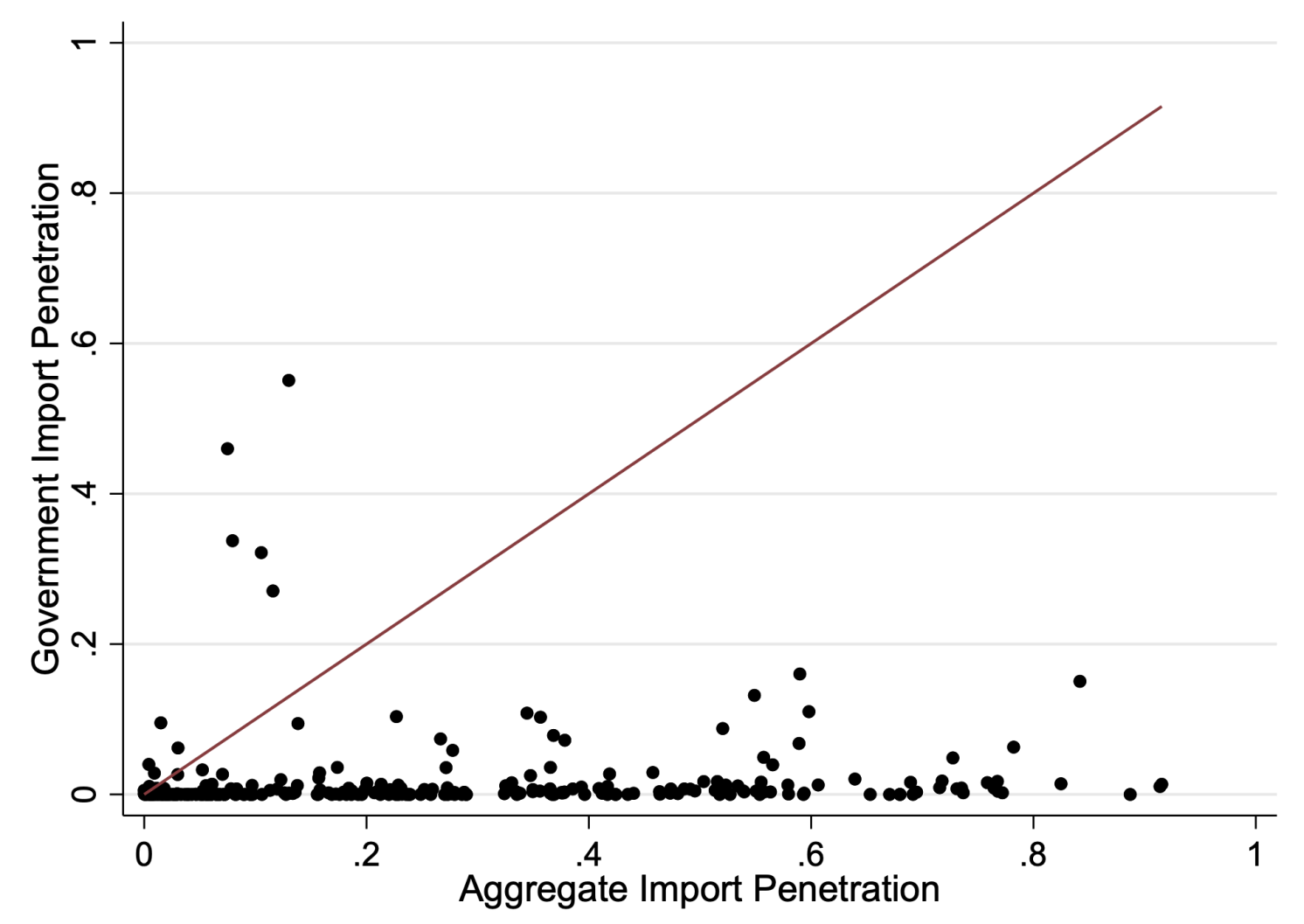

A major advantage of these granular data is their ability to reveal, industry by industry, the share of government consumption supplied by foreign firms, allowing for comparisons with the import penetration of private consumption. This comparison highlights how much more constrained the government is than the private sector in its ability to source goods. In Figure 2, we show how industry-specific (NAICS6) government import penetration ratios are significantly lower than aggregate figures. Most industries fall to the left of benchmark values from Hufbauer and Jung (2020) and Mulabdic and Rotunno (2022), calculated using international input-output tables which cannot distinguish import usage by final consumer (government versus households).

Figure 2 Aggregate and government import penetration ratios at NAICS6 level, only manufacturing

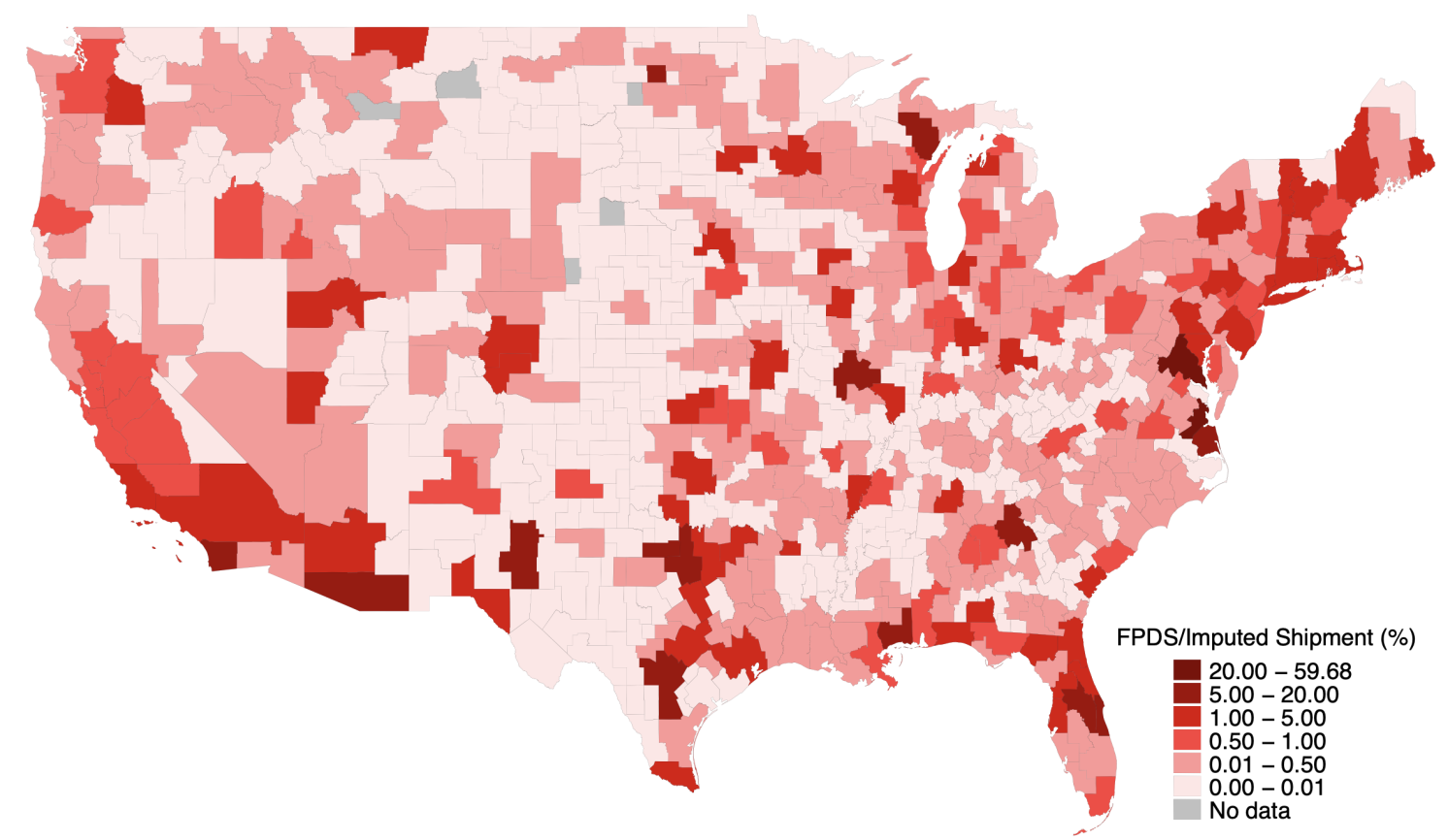

A second advantage of our data is that they allow us to map the geographic distribution of government purchases. Figure 3 reveals significant spatial variation in procurement shocks across US commuting zones. Using a shift-share instrument, we highlight the sizable impact of procurement spending on labour markets: an increase of $2,947 per worker (equivalent to one standard deviation) in government spending on goods produced within a commuting zone over a five-year period boosts manufacturing employment as a share of the working-age population by 0.47 percentage points.

Figure 3 Ratio between federal procurement spending and total shipment at the commuting zone level

To assess the welfare costs and benefits of the BAA (including employment and industrial policy considerations), we extend the quantitative model in Caliendo and Parro (2015) to include features relevant to the BAA. Consumers’ welfare depends on their consumption from both private market goods (as in traditional models) and public goods produced across different US regions (e.g. national defence and national parks), funded by the government through labour taxes. However, due to BAA provisions, firms producing for the government face higher trade barriers and production costs than those in the private market, affecting both final and intermediate goods. We include workers’ labour supply decisions across sectors and with respect to non-employment, and we account for sector-specific external economies of scale, where productivity is influenced by overall sector employment. Within this framework, stricter government policies on sectors with strong economies of scale could improve welfare.

By combining our model with a comprehensive trade matrix that includes both government and private consumption, as well as final and intermediate goods, we provide the first quantification of the effective trade barriers imposed by the BAA. Our findings indicate that BAA restrictions on final imports are significant, leading to a 96% reduction in government imports for the average manufacturing industry. Although the current wedges on intermediate inputs are not yet restrictive, upcoming changes are expected to extend their impact to several additional sectors.

Driven by these results, we use our model to conduct a series of counterfactual exercises by applying the exact hat algebra method (Dekle et al. 2007) and examining the potential effects of announced and possible future changes to the BAA. We first simulate the impact of lifting BAA-related import restrictions, effectively creating a scenario of free trade for the government sector. This change would result in an estimated loss of approximately 100,000 manufacturing jobs, at a cost of $132,100 to $137,700 per job in terms of equivalent variation. However, we recognise that completely removing these provisions is unrealistic for industries connected to national security. To address this dilemma, we use a specific clause in the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) to identify sectors with national security concerns. Incorporating this consideration only slightly reduces the magnitude of our estimates.

Second, restrictions on foreign intermediate inputs are set to become considerably tighter under policies introduced by both President Trump and President Biden, raising the minimum required share of US components from 50% to 75% by 2029. Our model predicts that this tightening will increase domestic employment by 41,300 manufacturing jobs. However, this comes at a substantial welfare cost, estimated between $154,000 and $237,800 per job. The “increasing cost of Buying American” thus arises from two primary factors: first, newly protected sectors that compete with foreign intermediate inputs generally have a lower labour share compared to those shielded by final goods restrictions. Second, regions most impacted by the increase in input costs are those with significant government procurement activity, resulting in higher public goods procurement costs.

Regarding external economies of scale, we uncover two significant findings. First, when running counterfactuals with and without external economies of scale, we observe that most of our prior results remain largely unchanged. This indicates that the current stringency of the BAA does not align with the strength of external economies of scale. In other words, BAA provisions are not targeted effectively at sectors where industrial policy could yield the greatest benefits. Inspired by this insight, we conducted an exercise whereby BAA wedges were redistributed across sectors to align perfectly with the strength of economies of scale. This adjustment resulted in a modest welfare gain of $3.69 per capita, accompanied by an employment reduction of 13,700 jobs.

Taken together, our findings suggest that while these policies can enhance domestic employment, they also come with increasing welfare costs, raising questions about the economic implications of strengthening domestic content requirements in government procurement.

See original post for references

I can’t comment much except to say that American TV is sh%t. And often relies on Americanisng UK TV series.

Beat UK Shameless.

Wouldn’t the worse effect of “buying American” that you actually get American stuff? Boeing, anybody? Is there anything of quality that is not a punishment to use or own (or trying to own) coming from the US?

At the time when the Germans had not lost their minds yet they told Trump some truth: build better cars.

https://www.marketwatch.com/story/german-minister-to-trump-after-tax-threat-the-us-needs-to-build-better-cars-2017-01-16

The bigger problem is that the US is no longer the “best” at many things.

You could argue about the US auto industry, the airplane industry, the computer chip industry, etc, but the point remains that the US has increasingly lost leadership in technology, quality, and price.

The Chinese tend to dominate in price, but increasingly, they are becoming the leader in technology as well.

My impression is that the US elite and American people as a whole really have not internalized this reality as a whole. American companies tend to prioritize share buybacks, short term profits, executive compensation, or outright looting by private equity. That’s just not going to work against the Chinese or other industries.

Buying American will not only cost more, but also lead at times to inferior quality products. It would take decades to get the US manufacturing base back up. Then there’s no assurance that the US would be able to catch up to the Chinese.

Somebody wrote recently: the American oligarchy don’t know how to do anything. Inbred trust-fund kids with no skills whatsoever but they really want their money. Their wealth is financialized and whence “share buybacks, short term profits, executive compensation, or outright looting by private equity”.,

Unfortunately this is an accurate take. The US has low social mobility and high inequality.

https://equitablegrowth.org/the-american-dream-is-less-of-a-reality-today-in-the-united-states-compared-to-other-peer-nations/

So really that means that the US does indeed have an elite that have inherited their wealth, and based on their actions, are hyper-greedy, but they are lacking in competence.

They haven’t done anything recently, that I could consider to be a win. I suppose by their twisted metric, looting to make themselves richer is a win. Their wars ultimately end up backfiring and their looting is starting to show major political backlash.

Going back to the problem, buying American requires there to be a vibrant American manufacturing sector and construction sector for there to be American products to actually buy. That’s a lot harder to do now that the US is deindustrializated in many fields and it takes decades to build a new industry up.

It goes back to the basics: “Meritocracy motherfucker; do you speak it?”

If you drop meritocracy, make progression dependant on money or connections or nepotism, then you inevitably end up with puddings, fail-sons and the unqualified clogging up the ranks of your entire system. You don’t even have to drop it, or everywhere, just reduce its impact in your “elite” institutions and hey presto, 20 or 30 years later you’re running out of ammunition in a major war you started for twitter kudos.

The colder reality is that as your institutions erode the criminal element seeps in to fill the civic void.

like my nemesis, the jones act. crushing our merchant marine potential because buy america: more expensive, worse quality.

This is a good piece for data, but the results don’t strike me as too surprising. Like all forms of protectionism, you keep some employment (and more obsolete physical capital), but it comes at a premium.

It’s maybe off topic since the authors don’t venture into policy advice, but I still stand by one point. Anyone in the US that promises balancing trade without at least saying the words “capital controls” is blowing hot air

We’ve had readers here speak up and say how crapified American tools have become for example while superior quality tools are to be found from overseas companies or – irony of ironies – sourcing American tools made a generation or two ago. Those products like tools have been crapified by the financial whiz kids who take money from production and quality assurance and spend it on advertising instead. Buy American sounds like a great idea but it goes back to that Buy American Act of 1933 at a time when America produced quality goods at a cheap price. A lot has changed since then. Too much.

American made tools or American brands? I find American made goods to generally be pretty good. American branded good on the other hand is no better and sometimes wise than generic stuff from Asia.

The devaluation of the Japanese yen is showing up in Amazon drop shipping options. The prices on high quality Japanese knives and gardening tools are very good right now.

you seem to miss out on is that china, and now russia, are protectionist. china only buys what it must, but sells all they can. open markets or free trade, simply does not work. america became a rich super power under protectionism.

the U.S. looks more like the ottoman empire every day, a country ruined by free trade, could no longer arm themselves, financialization, religious extremism, and sectors of society elevated over everyone else for policing, and immune from their crimes, then one day those elites almost took over.

china, now russia and iran make everything they can locally, and are producing massive robust supply chains. that is the real efficiency. beware of economist who preach efficiency.

you cannot do targgeted industrial policy in a nation as large and diverse as america.

i am sure china does a lot of stuff they lose money on. but the robust supply chains under socialism more than make up for the losses.

america is at the point now, where it can ill afford to lose anymore production, no matter how trivial it is.

Huh? Russia was absolutely full of Western consumer brand vendors. It had to take a lot over like KFC and McDonalds because they were in limbo-land after the sanctions and Russia wanted to preserve jobs. Responses to sanctions do not = protectionism. Putin is very much a neoliberal but the West hating him has gotten in the way.

yes russia took them over, and that’s my point. try that in america or the u.k. a form of forced protectionism was the results of the sanctions

i have no illusions about the russian leadership. they are a by-product of the idiot gorbachev, and the gangster yeltsin.

if russia is to survive, that neo-liberal thought must be extinguished, other wise they will find out that they will not be part of the WEF club, and not viewed at all as equals, but as prey.

china knows how to do it, at least so far, if the free traders get in their way, or try to over lord it over them, or get to uppity as some of their oligarchs have found out.

china will lose vast sums of money to out compete them, replace them, make them a state vassal, or in the case of some, they simply disappear.

The Russians are not protectionist. They invited Indian companies in after the sanctions to set up major retail stores.

Putin is a neo-liberal. See this: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1041&context=emancipations. A lot of other academic work like that. His central bank head since the early 2000s Elvira Nabiullina is most assuredly neoliberal.

You need to stop fabricating.

My hobby horse: Take the responsibility of providing medical care away from businesses and that will their costs across the board and make them competitive. Their international competitors don’t have to pay this cost.

I still remember Iacocca saying that Chrysler’s health care related outlay was way more than the outlay for all the steel that went into their cars and trucks.

I too remember when it looked like many large American corporations were very close to asking the government to step in and take over providing health care. At some point all talk of this seemed to disappear just like all talk of Medicare for All after Sanders was pushed out of the Presidential race.

This would seem like a fairly common sense thing to do if the country is serious about resurrecting American industry.

These provisions, which serve as barriers to the import of goods, create welfare costs by reducing import shares compared to free trade conditions. Hmm, “free trade” you say.

Here in WA the State Ferries are in a REAL mess with 50-odd-year-old vessels breaking down, and needing more maintenance. The state can’t buy foreign-built vessels, even though there are cheaper and better ones out there, due to an early-20th-century statute.

As a result, the system is unlikely EVER to recover its full service, including the now-closed route to BC, and I can’t realistically see it improving much before 2028-9 at the earliest.

The Seattle yard that built the ferries, Vigor, is not interested in building more because they were bought by PE and are now focusing on getting rick from pork-heavy federal defense contracts.

I know we have a regular commenter here, David from Friday Harbor – being on San Juan, which has only ferry and local air access to the mainland, I know he will be feeling the pain too…

For us, the pain is lessened because we are now retired and so can choose to travel to our Whidbey house at times whe we know the ferries are not full. Not many people have that luxury.

There are other factors in the mess the state ferries are in. First the Enslie admin neglected maintenance on existing diesel ferries in favor of building electric ferries- which are over budget, not performing properly, and late. Further, Enslie fired any ferry workers who refused the COVID jabs. This led to widespread crew shortages and canceled sailings.

It’s more about these failures by the Enslie administration than the quality of US manufacturing. Note these are primarily ideological decisions, in which competence, service, and the citizenry were secondary.

No arguing with HOW they got in this state – Inslee (sic), and before him, Gregoire neglected WSF (vessels and staff). BUT, the the must-buy-USA-ferries rule means that the hole is MUCH harder to climb out of. Hence this post in this thread on the cost of buying American.

Washington State manufacturing is solid – it’s not a rust belt situation. Consider all the parasitic weakening of Boeing – it’s still a powerhouse, despite decades of financial parasitism. Shipbuilding is a skillset which still exists in WA as well. It’s not like it requires Chinese rare earths and the like – it’s industrial manufacturing. IMHO the article, and the zeitgeist in general, is far too oh woe is me about US manufacturing prowess. Just get the incompetent ideologues out of the way with their elevation of other factors than competence. Inslee just lost an election and it’s highly unlikely he’ll ever get elected to anything again. Good riddance.

If we don’t start pursuing reindustrialization now, or soon, then when? Ever? Never? Give up and die off?

This post examines ‘buy national’ promotions and ‘buy national’ provisions in public procurement through the lens of economic models, welfare costs and benefits, and majorly advantageous “granular data” to obtain conclusions of little illumination. I believe the main problem is that all these fine tools of economic analysis make a lot of implicit assumptions about the u.s. economy and really assumptions about Political-Economy that best fit imagination and author desires rather than the real world and some of its difficult departures from the economists imagined worlds. — Too many important factors were ‘exogenous’ to the economic models and theories.

Consider the ‘buy national’ provisions in public procurement. When I worked in the Defense Industry I recall all sorts of waivers and ‘adjustments’ made in how ‘buy national’ was applied. I remember when there were campaigns to ‘Buy American’ and all kinds of labels showed up to declare “Proudly Made by American Labor”. But look into the details of these claims and especially the clever definitions of what Made by American Labor actually meant and what American Labor went into goods “Proudly Made by American Labor”. My conclusion was that ‘buy national’ was a campaign designed to encourage consumers to pay more for fancy labels.

I doubt the post’s economic models take into account the magnificent consolidation of u.s. Corporations. As I recall, the last time u.s. Corporations had an excuse to raise prices, they did, magnificently, and they had the Market power to reap fat profits as a consequence. Somehow classic demand-supply theory, models of competition, and other paraphernalia of economic theory offered fine rationalizations for what happened and a few false theories. And u.s. consumers ended up paying more for the same and lesser goods while enduring a ‘cure’ involving hikes in the interest rates on credit card debt and home loans.

My observations from a water well construction perspective:

Buy American specifications do make projects slightly to moderately more expensive. The real cost is time. I’ve had well and pump projects delayed by years because the US-made steel casing, steel pump column, pump/motor/drive components have enormous backlogs. This was true pre-2008 but really accelerated (more like decelerated) since then. Manufacturers offshored production, consolidated what domestic production remained, often into a single giant (non-union) factory, and raised prices. They now have no means to increase domestic production and no incentive to expand. I’ve found this especially true with paint, of all things. There’s a delay for the steel and another delay to paint it.

When you’re a small business trying to balance workload, a 1-2 year delay can be a huge problem. You might not have time/people available to do the work when it finally starts and delaying the project also delays the revenue.