Yves here. Richard Koo, famed for his creation of “the balance sheet recession” to explain Japan’s lost decades of growth, offers a fresh angle on why US and Japanese voters have gone into “Throw the incumbents out” mode. As many do, he sees Trump’s rise as strongly tied to the loss of manufacturing jobs. But Koo highlights the strong dollar as central to this development. He puts the starting time as 1987, as of the Louvre Accord. It’s actually earlier.

The dollar spiked up after Volcker abandoned his super high interest rate regime, I was in London in summer 1984 when the greenback was at 1.10 to the pound; it later rose to 1.03.

During the 30 months of the dollar surge, Japanese automakers gained market share bigly to the Big Three and never gave it back. Mind you, American automakers were in the midst of the fallout of their refusal/inability to build cheaper, more fuel efficient cars. But the dollar surge both greatly accelerated their decline and made it seem even more futile to try to respond.

The US and the other members of the then G-5 agreed in 1985 to implement the Plaza Accord to drive the yen up. They did, even more so than intended, leading to the corrective Louvre Accord in 1987. What is not well remembered from that era (I was then working with the Japanese) is that even though the big fall in the dollar did dent Japanese imports to the US, it did nothing to boost Japanese imports of American goods. Japanese strongly preferred Japanese products and regarded US wares as inferior.

Pegging the strong dollar era earlier also ties it more strongly to when US average wage growth started diverging from productivity growth (1976).

By Richard Koo, Chief Economist of Nomura Research Institute with responsibilities to provide independent economic and market analysis to Nomura Securities, the leading securities house in Japan, and its clients. He is the author of many books and articles. Adapted from a report published by Nomura, cross posted from the Institute of New Economic Thinking website

Why ruling parties were defeated in US and Japanese elections

Big political changes are afoot in Japan, the US, and Europe. The US and Japan held national elections in the past few weeks, and in both cases the ruling party suffered a major defeat, creating heavy uncertainty over economic policy. In Germany, meanwhile, the withdrawal of the Free Democrats Party (FDP) from the three-party coalition has left the government in a predicament.

What is common to all three regions is growing popular anger over the economy despite high stock prices and low unemployment. In the US, the macro-level data are reasonably strong, but many people are simply not benefiting. In Japan, import inflation has weighed heavily on household finances, and Germany is suffering from a serious economic slowdown.

US asset prices have surged over the last 40-odd years, but wages have hardly budged

Turning first to the US, I think many people expected the incumbent Democrats to be returned to the White House given the relatively low unemployment rate, solid GDP growth, and high stock prices.

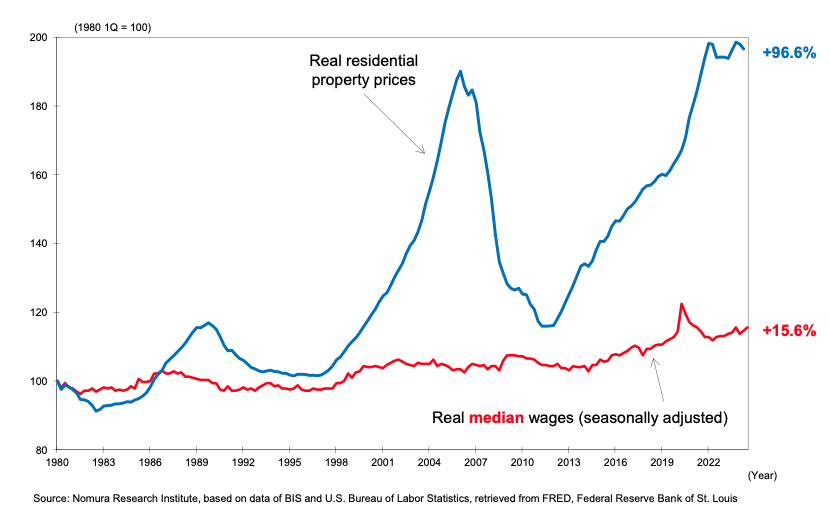

But as noted by David Smick, director of a documentary titled “America’s Burning” that was recently released in the US, the DJIA has risen 5,000% in the 43 years since 1980, but the real (median) wages of ordinary Americans have increased by only 15%. Since this is a median value, it means that fully half of all Americans have seen their real wages rise by less than 15% in the last 43 years.

What is happening in the stock market may not affect the living standards of the people directly, but inflation-adjusted housing prices, which have a direct impact on household finances, have soared 96.6% (Figure 1). The fact that the real wages of the ordinary Americans seeking to buy these houses have risen by only just over 15% makes it clear in many senses that their standard of living has declined. It should not be surprising that they are so unhappy with the current system.

Figure 1: Real housing prices and real wages in the US

Globalization-driven “hollowing-out” of industry is one reason for sluggish wages

We next need to ask why real wages are so depressed. At least one contributing factor has been the movement toward globalization symbolized by the outsourcing of manufacturing. Now that companies in many developed economies are able to utilize inexpensive labor in emerging markets, they have no reason to continue paying high wages in their home countries.

This phenomenon is said to have begun when Taiwan created three export processing zones in Kaohsiung and elsewhere between 1966 and 1971 and invited foreign companies to build factories there to tap the local pool of cheap labor. China then launched its reforms and open-door policies in 1978, the Cold War came to an end in 1989, and in 1992 the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was signed. All of these events served to fuel the spread of globalization.

Prior to this era, it was difficult for companies in the developed economies to take advantage of inexpensive labor in emerging markets: China had a communist planned economy, Southeast Asia had been thrown into turmoil by the Vietnam War, Russia and Eastern Europe were on the other side of the Iron Curtain, and Latin America and India were pursuing an import-substitution model of economic growth.

Globalization has brought great benefits to capitalists, companies, and consumers, but it has had serious adverse effects on the workers in domestic manufacturing and agriculture who must compete with inexpensive products produced overseas.

Neglect of strong dollar and trade deficits has created severe divisions in US society

Companies in Japan and Europe have also taken full advantage of globalization, but social divisions in the US have grown much wider than in other developed economies. Why is this the case?

As I have argued previously, I believe the problem can be attributed to the strong dollar and the trade deficits it produced.

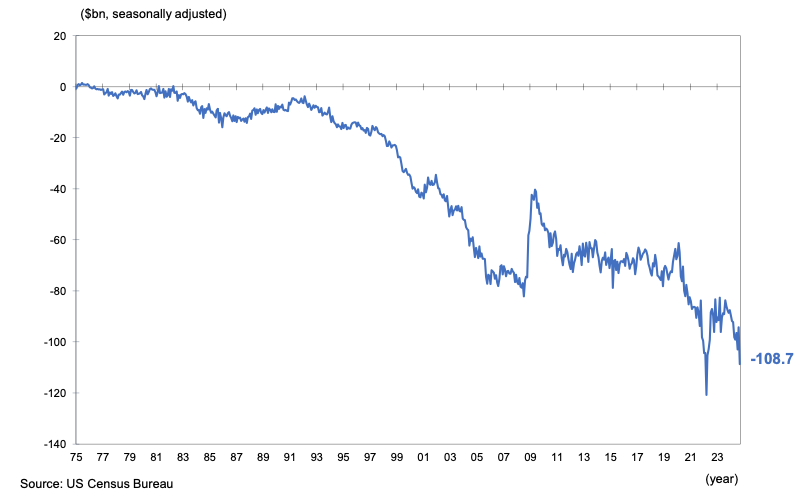

US trade deficits were not a big problem through the late 1970s. However, they increased dramatically starting in the 1980s and have stayed that way for more than 40 years (Figure 2).

Figure 2: US balance of trade, 1975 to present

As a trade deficit directly reduces GDP, the vast majority of countries worry about running larger trade deficits unless the imported goods responsible for those deficits are capital goods essential to future economic development.

40-plus years of US trade deficits amount to 153% of GDP

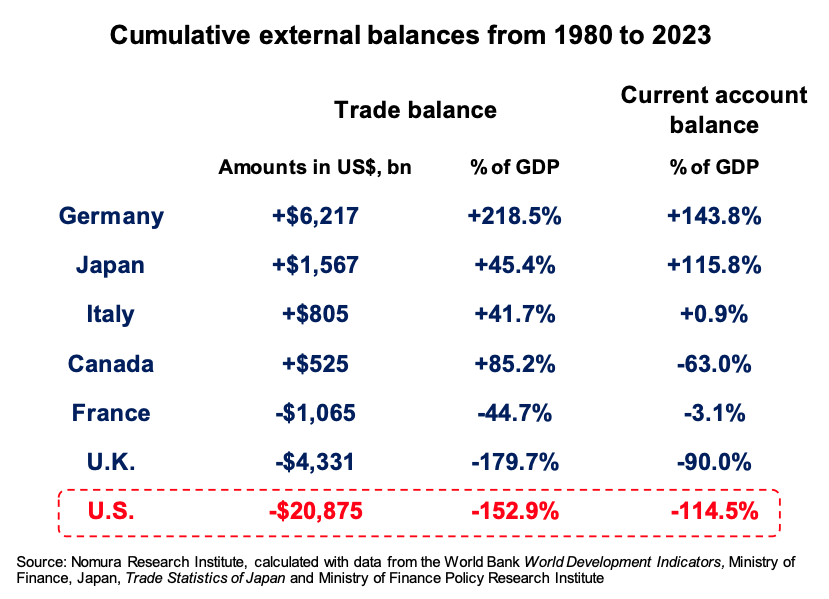

However, the US has turned a blind eye to those trade deficits for more than 40 years. As a result, the nation has lost cumulative income equal to 153% of GDP since 1980 (Figure 3). This 153% equates to $20.8tn if we simply add together the trade deficits at the time, or to $41tn in today’s dollars.

Figure 3: Cumulative external balances from 1980 to 2023

The cumulative US trade deficit as a percentage of GDP is the second largest in the G7 after the UK. However, the UK earns financial services income because London is a global financial center. When we look at the current account, which includes such income, the US ranks last among the G7.

The reason why I am focused on the balance of trade, however, is that trade deficits are directly linked to manufacturing and involve a tremendous number of blue-collar jobs, whereas in the financial sector, a relatively small group of people handle large volumes of money. As such, I think trade deficits are more useful in analyzing social divisions and election results.

In contrast to the US, countries like Japan and Germany are running large trade surpluses, as shown in Figure 3, and the GDPs of those two countries have benefited greatly from trade despite globalization.

The overly strong dollar was neglected because capital flows were liberalized

I attribute this difference to the fact that the US has paid no heed to the strong dollar for the 37 years since the Louvre Accord in February 1987. As discussed in detail below, the massive US trade deficits could not have continued so long without a strong dollar, which naturally proved highly beneficial to US trading partners.

This strength in the dollar began with major changes in the participants of the foreign exchange market resulting from the developed economies’ decision to allow the liberalization of cross-border capital flows starting in 1980. Prior to that, the main participants in this market were importers and exporters. Their transactions automatically served to lower the value of currencies of trade deficit nations and increase the value of currencies of trade surplus nations. This helped prevent excessive growth in trade imbalances.

But from the 1980s onward, portfolio investors and speculators became the main participants in the forex market, and as they stepped up their purchases of high-yield dollar assets, the greenback rose to levels that could never be justified given the size of US trade deficits. Moreover, while the US government sharply lowered the value of the dollar with the Plaza Accord in September 1985, it has never tried to address subsequent dollar strength since the Louvre Accord that signaled the end of the earlier correction.

In short, the US has turned a blind eye to the strong dollar and the resultant 41 trillion dollars worth of outflows of income from its manufacturing and agriculture sectors for more than 40 years, and that is most likely why—despite experiencing the same globalization trend as countries like Japan and Germany—the US has seen social divisions widen to this extent.

Trump forced both US parties to jump from free trade to protectionism

The people who have suffered from these trade deficits for more than 40 years are the core supporters of President Trump. This can be seen from the fact that protectionist measures to defend domestic industry and workers were essentially the only concrete policy proposal he offered in May 2015, when he first announced he was running for president. The fact that this so quickly grew into a massive political phenomenon tells us just how many people have been harmed by trade deficits over the years.

Mr. Trump’s championing of protectionist policies enabled him to immediately win the support of a huge number of blue-collar workers. The Democratic candidate, Hillary Clinton, was shocked to see this and responded by abandoning the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) that she herself had helped negotiate (it was said to be the most advanced free-trade agreement ever) and reversing course in favor of protectionism. But it was already too late, and she was defeated by Mr. Trump in the 2016 presidential election.

President Biden, who took back the White House from Mr. Trump after the latter’s botched response to COVID-19, not only did not rejoin the TPP but left nearly all of President Trump’s tariffs in place and even raised some on his own.

This was evidence that the two major US political parties had finally begun to think about the victims of the massive trade deficits that they had allowed to fester for the preceding 40 years.

Why did Vice President Harris not campaign on trade issues?

The Republican Party was also surprised to see the depth of support for Mr. Trump and did an about-face on its traditional support for free trade. Today it has transformed itself into Trump’s party and is a proponent of protectionist policies.

Then-President Barack Obama, whose party was responsible for creating the TPP, knew there was no way the treaty would be ratified in the US without the support of the Republican Party, which had traditionally been a leader of the free trade movement. However, those same Republicans have now outdone the Democrats—traditionally skeptics of free trade—and become full-fledged supporters of protectionism.

The unanswered question is why the Democrats in 2024 were unable to learn from their mistakes in 2016. Although they knew that trade and industrial revitalization would become key campaign issues if they faced former President Trump, President Biden and Vice President Harris avoided these issues almost entirely.

If we assume that most of Mr. Trump’s supporters were supporting him because of this issue, Vice President Harris should have tried to whittle away at his support among this group by presenting concrete policies to address their concerns. Yet the Democrats did almost nothing in this area.

Biden effectively spurned trade deficit victims with a comment endorsing a strong dollar

In fact, President Biden went so far as to declare that he was not worried about the strong dollar. In response to the dollar’s sharp move higher a few months earlier, he memorably said, “Our currency, their problem.”

He was effectively saying that he would turn a blind eye to the strong dollar because it only caused problems for other countries, not the US. In fact, however, there are many Americans who have been harmed by a strong dollar, and most of them have become supporters of former President Trump. It is therefore hard to understand why Mr. Biden would declare to people suffering from a strong dollar that he planned to do nothing about it.

Democrats lost because they failed to approach victims of strong dollar and trade deficits

A famous economist considered a leading figure in the Democratic Party said that a weak-dollar policy should be avoided because it would lead to higher inflation. While this may be a reasonable argument when inflation is a problem, in practice it raises some fairly serious political issues.

A government that implements a strong-dollar policy to curb inflation is essentially saying that it plans to turn up the pain for people who are already suffering from the rising trade deficits caused by a strong dollar. This will seem extremely unfair to those who work in industries that must compete with imported products.

If there were only a few victims of the strong dollar and the trade deficits it causes, the election impact might indeed be minor. But given that a majority of the other party’s supporters had in fact suffered from currency and trade policy, I think this message was clearly counterproductive—particularly since it came at a time when support for the two candidates was so evenly matched.

In contrast to the way the Democrats largely ignored the strong dollar and trade deficits, former President Trump responded to the dollar’s surge above 160 yen by warning in no uncertain terms that this was a huge mistake for the US.

Vice President Harris was initially well-received by all quarters when she announced her candidacy, but she was unable to attract wider support because she did not even try to whittle away popular support for former President Trump. That forced her to contest the election with only the Democratic Party’s traditional supporters, and she ultimately lost to Mr. Trump in all of the key battleground states.

Democratic Party supporters tend to be insulated from the impact of a strong dollar

In recent years, supporters of the Democratic Party have tended to be highly educated urban dwellers who work in service sectors like finance, media, or academia. In this election as well, the Democrats dominated in nearly all major cities like New York and Los Angeles.

But these people are almost entirely insulated from the downside of a strong dollar. Of the 16 Nobel-laureate economists who joined a campaign encouraging people not to vote for former President Trump, I suspect few had ever felt the pain of watching one’s industry be hollowed out by a strong dollar.

If any of them had gone through such an experience, I suspect they would have quickly mentioned this to Vice President Harris and urged the Democratic Party to come up with an alternative policy to the protectionism of Mr. Trump.

Similarly, I think few if any of the investors and speculators who made money betting on the strong dollar in what was called the Trump trade gave any thought to the negative impact a strong dollar would have on US industry and the people it employs.

Distrust of the establishment returned Trump to the White House

Until Mr. Trump first declared his candidacy in 2015, it was these high-income, highly educated “elites” who formed the mainstream of both the Republican and Democratic parties. And it was the victims of the trade deficits and industrial hollowing-out caused by those same elites’ neglect of the strong dollar for nearly 40 years who came out to support the former President.

From the perspective of Mr. Trump and his backers, there is no reason why they should pay any attention to the logic or common sense of an establishment that had caused them and their families such great harm.

This situation is reminiscent of what Einstein said about the futility of trying to solve problems with the same thinking used to create them. While we might find public statements and policies of Trump appalling, they would simply argue that it is impossible to fix the economy using the same ideas that broke it in the first place.

And by “broke,” I am referring to the fact that real wages have increased only 15% over the last 40 years.

Trump is good at challenging existing norms but may have difficulty building new structures

To be sure, breaking away from the past does not necessarily lead to bad consequences. In his first term, for example, Mr. Trump defied one of the unspoken rules of US diplomacy in the preceding decades—that no president should meet with the leader of North Korea given its human rights problems—and met with Mr. Kim in Singapore in June 2018, quickly easing the tensions that had built up between the two nations.

I think this meeting was a great success in as much as it narrowed the rift between the US and North Korea, and it would have been unthinkable under any other president.

Unfortunately, the two leaders’ next meeting, in Hanoi, broke off because President Trump had done no homework for the meeting, and consequently tensions heightened again and have stayed that way ever since. This suggests that while as an outsider Mr. Trump may be able to push past traditional constraints, he may have difficulty building new frameworks to replace the old ones.

The mistaken belief that everyone benefits from free trade caused Democrats to let down their guard

The next question is, exactly what did the elites—including the 16 Nobel laureate economists noted above—get wrong, and how? One thing is the way the idea of free trade is taught in schools.

Conventional economics holds that free trade creates winners and losers within a national economy but is a net positive for the broader economy because the benefits accruing to the winners are greater than the losses sustained by the losers. This suggests there are always more winners from free trade than there are losers.

But arriving at this conclusion requires making a huge assumption that no one seems to have noticed—namely, that the nation’s trade account must be balanced or in surplus. If the country is running a massive trade deficit and those deficits persist over many years, the number of losers from free trade will continue to grow. Eventually, it will produce a situation in which, as in the US presidential elections of 2016 and 2024, the losers have enough votes to send a protectionist like Mr. Trump to the White House.

Democrats tend to have closer ties to so-called mainstream economists than Republicans, but it would appear that none of those economists had considered the possibility that free trade could produce more losers than winners.

In contrast, the Republican Party recognized this possibility after witnessing the Trump phenomenon in 2016 and quickly changed its stance on free trade, as noted above.

Elected politicians cannot implement policies based on I/S balance theory

In addition, many mainstream economists argue that US trade deficits reflect an excess of US investment (I) over savings (S), and that unless this problem is addressed any attempts to weaken the dollar will only end in failure. In effect, they are saying that the US runs trade deficits because it relies on overseas manufacturers to provide the things it cannot supply for itself.

This is identical to the so-called Komiya theory that was formerly popular in Japan, but it utterly fails to explain what has actually happened in the US. If the theory were correct, US companies competing with imports should have been posting large profits since domestic demand was so much greater than domestic supply. In reality, however, the vast majority of them were unable to compete with inexpensive imports given the persistent strength of the dollar, and were ultimately forced into bankruptcy. In short, trade deficits and the hollowing-out of US industry can be explained by a strong dollar but not by the I/S balance theory.

Moreover, the I/S balance theory which holds sway among many academic economists argues that, in order to reduce trade deficits, policies are needed to depress domestic demand. But such policies that would lead to recession were off-limits to elected politicians. And that is one reason why trade deficits have been neglected up to the present day.

The Plaza Accord has been largely forgotten by scholars and market participants

Furthermore, many economists and foreign exchange market participants argue that even if the governments desired a weaker dollar, the central banks of the world simply do not have enough funds to intervene on the greenback’s behalf, making it impossible for them to alter exchange rates.

Here it would be well to remember the Plaza Accord, which was implemented starting in September 1985 by President Reagan with the help of the other G5 (subsequently G7) nations. The agreement was signed at a time like today when the strong dollar had produced powerful protectionist pressures within the US and was extremely successful in relieving those pressures by halving the dollar’s value against the yen.

Space constraints force me to leave a detailed discussion of why this approach was successful to my book (Chapter 9 of Pursued Economy: Understanding and Overcoming the Challenging New Realities for Advanced Economies). Unfortunately, 39 years later, there is almost no one in US political, financial, or academic circles today who remembers why the Plaza Accord was signed and what it produced.

Because of all these incorrect notions, the Democrats were unable to offer a counterproposal to the protectionist policies of former President Trump. Indeed, if those incorrect notions were actually correct, then protectionism is the only logical remedy for those who are suffering from the strong dollar. I think that at least some of the responsibility for that loss lies with the economists who were making bad economic arguments.

Free trade emerged from the failures of protectionism

The next question is whether the protectionist policies espoused by Mr. Trump can save the people who are asking for his help. Unfortunately, the trade wars of the 1930s suggest the answer is probably “No.”

In the 1930s, the global economy was thrown into turmoil by the sharp increases in US import duties implemented in 1930 under the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act and the retaliatory tariffs by other nations that followed. The value of global trade plunged 66% from the peak, and economies around the world suffered heavily.

The resulting economic turmoil eventually led to World War II. The US, which got through the greatest tragedy in human history by mobilizing its military capabilities, decided the world must never repeat this mistake. To that end, it introduced the system of free trade symbolized by the 1947 GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade).

This US-led free trade system produced unprecedented prosperity for humanity, but cracks began to appear when the nature of the currency market changed after the developed nations began liberalizing capital flows in 1980.

Today, just as in the 1930s, free trade is facing a potential crisis in the form of a sharp increase in US tariffs. If the authorities seriously wish to avoid this outcome, I think the nations of the world must come together and carry out an exchange rate adjustment similar to the Plaza Accord.

Main trading partners of the US could allow their currencies to rise together

In the case of the Plaza Accord, it was President Reagan—a strong believer in free trade—who adopted a weak-dollar policy to defend free trade from protectionism. This time the situation is reversed, and the incoming US president is a strong believer in protectionism.

In that sense, it may be too late to walk back a problem that has been festering and growing for 37 years. But even if the US does nothing, it would theoretically be possible for other nations to forge an agreement like the Plaza Accord.

I think Japan, the UK, and the countries of Europe should cooperate with China and other trade partners to come up with a policy that will allow their currencies to appreciate by, say 20% against the dollar, in exchange for which they ask the US to forgo further tariff hikes.

A scenario in which other nations implemented such a policy without US leadership may seem highly unrealistic, and in any case, there is no guarantee that President-elect Trump would accept such a deal. But whereas Germany, France, and Italy each had their own currency when the Plaza Accord was signed, this time they are all using the euro, which only leaves Japan, the UK, Canada, and China. If these countries and the eurozone had a sufficient sense of urgency, the impossible might become possible.

It has also been reported that President-elect Trump once had great respect for the same President Reagan who ultimately saved free trade with the Plaza Accord.

While this may all seem like a pipe dream, I think it will be difficult to solve a problem that has been festering for 37 years without a plan of this magnitude.

Japan’s ruling party also lost because it failed to address the economy and inflation

Turning to Japan’s recent general election, there have been many reports saying the major defeat suffered by the ruling LDP was due to its slush-fund scandal. However, I think the party was actually done in by economic problems.

The LDP saw its proportional representation votes decline by 26.8% over the last election in 2021, but it was not alone in receiving fewer votes. Many parties found themselves in the same boat—in fact, the only two opposition parties receiving significantly more votes this time were the Democratic Party for the People (DPP), whose vote count surged by 138.0% over the last election, and Reiwa Shinsengumi (“Reiwa”), which saw a 71.7% increase.

Meanwhile, the Constitutional Democratic Party (CDP), which ran a campaign criticizing the LDP over the slush-fund scandal, received only 0.6% more votes. The Japanese Communist Party (JCP), which played a major role in bringing the funding scandal to light, garnered 19.3% fewer votes, and the Japan Innovation Party (“Ishin”) suffered a bigger defeat than the LDP itself, bringing in 36.6% fewer votes.

Both of the parties that garnered significantly more support in this election emphasized economic issues in their campaigns. In other words, only the two parties that put the economy front and center managed to win more votes, while the rest saw support stagnate or decline.

Japanese also angry with inflation, including a decline in real wages

This demonstrates that the issue of greatest concern to most voters is the economy, and in particular inflation—something I have noted in previous publications. The inflation Japan currently faces is raising the price of items consumers must buy every day, like energy and food, which is probably why people were so upset.

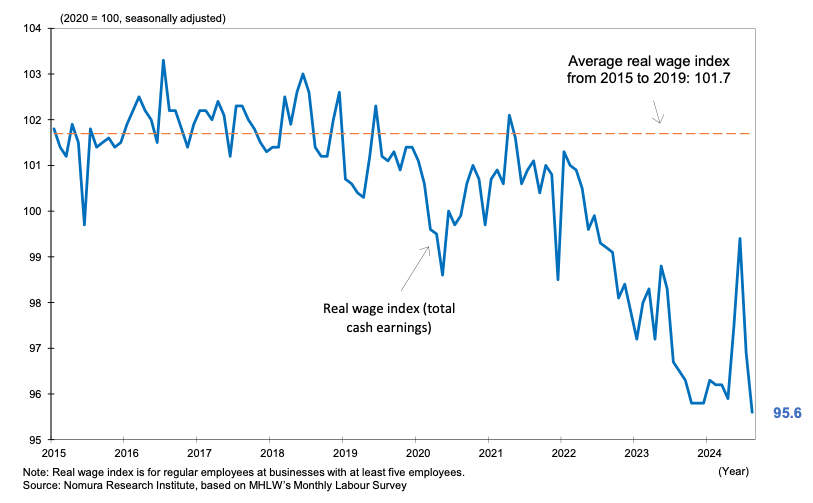

Real wages, which are directly tied to living standards, have fallen substantially as a result of inflation (Figure 4) and remain depressed in 2024 apart from a brief uptick driven by a big increase in summer bonuses.

Figure 4: Real wages in Japan

Notes: (2020 = 100, seasonally adjusted); Real wage index (total cash earnings); Average real wage index from 2015 to 2019; Real wage index is for regular employees at businesses with at least five employees. Source: Nomura Research Institute, based on MHLW’s Monthly Labor Survey

But the LDP—and particularly those who were close to former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe—continued to emphasize the benefits of and need for inflation in this election, just as Mr. Abe once did.

Unlike then, however, Japan is now experiencing inflation that is having a huge negative impact on living standards. The LDP was effectively standing up in front of people suffering from inflation and telling them how much the LDP contributed to higher inflation rates. It is hardly surprising that the party received fewer votes.

Inflation was never responsible for the strong Japanese economy

When there was no inflation, the arguments made by former Prime Minister Abe and former BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda—that the first priority was to end deflation and that the economy would improve once inflation took hold—were simply an expression of their hopes and had little adverse impact on election results.

At the time, moreover, those who remembered the horror of skyrocketing prices of the 1970s were already becoming a minority. Many held a nostalgic view of the distant past (until about 35 years ago), remembering only that Japan’s period of strong economic growth was accompanied by inflation. That may have led some of them to assume that a pick-up in inflation might jump-start the economy.

The actual causal relationship was quite different, however. The economy was strong not because prices were rising; prices were rising because supply could not keep pace with demand. At the time, moreover, relatively few factories had been moved overseas, so wages rose in both nominal and real terms as domestic labor market conditions tightened.

LDP was blamed for inflation because of its focus on Abenomics

When the asset bubble burst in 1990 and the balance sheet recession began, arresting growth in domestic demand, Japanese companies began to suffer from excessive employment. It was also around this time that moving factories to China or Southeast Asia became a realistic option for Japanese companies.

However, economists ignored deflationary factors such as globalization and balance sheet problems and instead blamed deflation solely on the policy errors of the Bank of Japan. There were many such economists in academia—including former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke prior to 2008—and they argued that the BOJ should try to stoke inflation, even if that required unconventional monetary accommodation.

The Bank of Japan responded to this pressure by taking interest rates into negative territory and carrying out astronomical amounts of quantitative easing. However, these measures prompted few to resume borrowing, and inflation failed to take root in Japan until the pandemic and the war in Ukraine triggered supply chain problems.

The LDP should have recognized at this point that the BOJ was not responsible for the lack of inflation and that something else was causing the economy to stagnate. But it did not, and instead continued to push for easy monetary policy that sought to amplify inflation. When the impact of inflation finally hit the pocketbooks of ordinary Japanese consumers, the LDP received all the blame for it, and that is why the election turned out as it did.

Most of the current inflation in Japan is import inflation resulting from overseas supply issues and is not actually attributable to the LDP. But because the party continued to insist on easy monetary policy, the yen weakened against nearly all other currencies, and what would normally have been a mild bout of import inflation grew into something much more serious.

In that sense, the fact that the ruling party fell for a specious economic theory at a time when the economy was a key concern for voters played a major role in the recent election results in both Japan and the US.

Raising the tax-free income threshold for part-time workers would ease labor shortages and greatly benefit Japan’s economy

The LDP-Komeito minority coalition will now have to work together with opposition parties—including the DPP, which won many more votes by focusing on economic issues—to pursue its policy agenda. I do think this is good in the sense that the economy will now become a priority for the Ishiba administration.

In particular, I believe a substantial increase in the ¥1.03mn annual tax-free income threshold for part-time workers sought by the DPP is a critical issue for a country facing severe labor shortages.

Some within the government estimate that raising the basic income tax deduction by ¥750,000, bringing the combined deduction to ¥1.78mn, would cost central and local governments a total of ¥7.6tn in forgone tax revenues. However, I suspect the assumptions underpinning this estimate would be very different for a scenario in which companies were suffering from excess personnel (as used to be the case) and one in which labor shortages have left many businesses unable to meet the demand for their products (as is now the case).

When labor shortages are a major bottleneck for economic activity, as is true today, the government should do whatever it can to ease the shortages by removing or altering the various barriers creating an artificial bottleneck. If such actions produced a rapid expansion of the economy, the resulting increase in tax revenues could be substantial. In that sense, I think we are fortunate that the election results have led to efforts to raise the annual income threshold (“wall”) for part-time workers.

I think now is also the time for the Ishiba administration to reestablish itself as an inflation fighter in view of the election results. But the stock market, where foreign investors have a great deal of influence, tends to prefer a weak yen. There is also the mystery of the Rengo trade union federation eagerly seeking inflation despite the already substantial decline in real wages.

It will probably be difficult for the minority coalition to build a policy consensus under such confused conditions, and it may take some time for it to arrive at a clear direction for inflation-related policy.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=gxkQ

January 15, 2018

Real Broad Effective Exchange Rate for China, Germany, India, Japan and United States, 1994-2024

(Indexed to 1994)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lF7e

January 30, 2018

Real Effective Exchange Rates based on Manufacturing Consumer Price Indexes for China, Germany, India, Japan and United States, 1994-2024

(Indexed to 1994)

Trump criticizes the weak yen, but he should understand that both the Japanese and the BOJ crave a strong yen, if possible, because Japan depends on imports for everything.

I would be interested in learning how things might have changed since then, but Japanese economist Makato Itoh wrote in 2005 that the appreciation of the yen against the dollar was a major concern for the Japanese government due to the impact on its export sectors. He identified this concern as one of the motivations for Japan’s purchases of US dollars, partly to slow the yen’s appreciation.

https://monthlyreview.org/2005/04/01/the-japanese-economy-in-structural-difficulties/

“In a December 2003 interview, Hiroshi Watanabe, Director General of the International Bureau at Japan’s Ministry of Finance, said even Toyota might struggle with less than 100 yen to the dollar, and for medium-sized enterprises and the service sector any further appreciation in the yen would be painful. He confessed he was “somewhat puzzled” by the European Central Bank’s apparent willingness to tolerate the steady appreciation of the euro against the dollar. Like Japan, he said, the core European economies need lower interest rates and a depreciating currency.”

Japan’s low export dependency means that only a few large export-oriented companies such as Toyota will benefit from a weaker yen, but the impact of those companies on the Japanese economy through their stock prices and employment is so large that it cannot be ignored.

HUH?

US exports to GDP is about 11% of GDP. Japan’s is nearly twice that, even after being pressured massively over decades to have more local manufacturing content.

thank you Yves for this post. I recall Mr Koo’s Balance Sheet Recession charts and his insightful commentary some years ago. His wise words enlightening as ever.

This article makes a lot of sense but few will be willing to eat the cat food this time. China has very different priorities now than Japan had then.

Think of it like 1936, everyone is re-arming at once and the capital controls that come with WW3 will turn a lot of this into a moot point.

My simple explanation is that corps are making record profits, that workers are getting a very small share of the pie. It may be that this is temporary, that strikes are getting more frequent and that labor, and labor unions, are stirring. But just now the oligarchs continue to get richer.

It does seem strange that we oimport more and more, run 800 bases overseas, and the dollar just gets stronger. There seem an insatiable appetite for green paper.

Gotta love his takedown of the 16 self-important, pompous economists, although the really short letter suggests they could not agree on much!

Thank you very much for posting this. Figure 1 is most interesting (at least to me). There seems to have been an incipient divergence between house prices and wages soon after the passage of the Garn-St Germain Depository Institutions Act 1982, which significantly liberalised residential mortgage credit, and led to the advent of the adjustable rate mortgage. However, the real divergence between house prices and wages appears to occur after the Taxpayer Relief Act 1997, which exempted the first $250k of capital gains from CGT (or $500k for a couple). The growth curve in house prices thereafter seems almost parabolic. The decade between 1997 and the GFC was also characterised by a massive construction boom, but the great increase in the supply of new houses seems to have made little difference to the growth in house prices.

The lesson for me is that house prices are less a matter of supply and demand dynamics, as of credit flowing naturally to where it is least taxed. The usurpation of the banks’ loan books by mortgage credit *arguably* crowds out investment in innovation, flattens productivity growth and, therefore, wages – and so makes owner occupiers that much more dependent upon house price appreciation for their future security: a malign self-reinforcing effect. The wealth effect derived from house price growth underwrites higher levels of consumption on imported goods, and so exacerbates the current account problem: again a baleful self-reinforcing mechanism. It is much the same with the UK where it is, at least proportionately, an even deeper and more intractable problem: in the UK the fiscal preference to owner occupation was established in 1963-65, and mortgage credit was liberalised, at least unwittingly and temporarily in 1971-73, and more especially from 1980, resulting in endless regressive housing booms.

Thanks for this comment. I especially liked “credit flowing naturally to where it is least taxed”. Usury wherever it is permitted. Gramm-Leach-Bliley gets all the bad press in current commentary, but it clearly was the Taxpayer Relief Act that opened the barn door.

“In fact, President Biden went so far as to declare that he was not worried about the strong dollar. In response to the dollar’s sharp move higher a few months earlier, he memorably said, “Our currency, their problem.””

Wasn’t this a case of Biden trying to channel the ‘manly’ spirit and swagger of John Connally? Kissinger famously called Connally ‘Nixon’s Walter Mitty image of himself’. Connally produced this quip – then thought to be outrageously offensive – in the Rome negotiations in late 1971 prior to the Smithsonian Agreement (which *perhaps* foreshadowed the Plaza and Louvre accords, insofar as it aimed at having surplus countries appreciate their currencies against the dollar in order to put the US back into current account equilibrium).

Yes, you have the origin correct.

Having recently read Adam Smith in Beijing, I am interested in the contrast between Arrighi (by way of Robert Brenner) and Koo in their respective assessments of the Plaza Accord. From Arrighi’s book I was left with the impression that the plaza accord was ultimately unsustainable, as the US’s growing dependence on inbound capital flows made a weak dollar unsustainable. He pointed to the 1995 appreciation of the dollar, which he called “the monetarist counterrevolution”, as resolving this tension for a time by pairing a strong dollar with credit expansion in order to maintain growth while taming inflation.

Obviously both him and Koo rightly see financialization as ultimately a non-solution solution, but I’m inclined to share Arrighi’s skepticism about the viability of the Plaza Accord when considered against the wider role the US came to play in stabilizing the capitalist system.

On its face the idea of other countries enacting a similar policy today seems ludicrous. tariffs can definitely inflict significant pain, and the US has demonstrated a remarkable ability to push self-destructive policies on its allies, but with the massive deficits it has run contributing to many of these countries holding enormous volumes of USD-denominated assets, how much pain (and for how long) would it take before countries deem it preferable to effectively set alight 20% of these assets?

For Canada alone, losses on just the USD portion of the forex reserves held in its exchange fund account would total $11.5 billion, and that’s without getting into losses inflicted on the CPP investment board, where at least half of its assets are US equities or otherwise USD-denominated securities, or the assets held by households, pension funds and the wider private sector. Conceding that perhaps an orderly and coordinated approach could mitigate some of the more extreme impacts, I still struggle to see what has changed between 1985 and now that would suddenly make a Plaza Accord 2.0 sustainable or even desirable for these countries in the long term. Barring some wider controlled demolition of US financial hegemony and reconstruction of the global economy, such an effort in the name of preserving free trade feels a lot like shutting the door after the horse has already fled the stable.

This is a tangent from the main thrust of the article, but I thought it worth commenting on.

> the big fall in the dollar did dent Japanese imports to the US, it did nothing to boost Japanese imports of American goods. Japanese strongly preferred Japanese products and regarded US wares as inferior.

This remains true up till now with the notable exception of the iPhone. It took a while but by about generation 4 of the iPhone, a lot of Japanese consumers enthusiastically started using it. I think Japan has probably one of the highest Apple:Android ratios in the world today. Just goes to show it wasn’t xenophobic snobbery keeping them from buying American but that until then for the most part American products truly were not up to snuff, or at least were not suited to the Japanese market. For example, I remember asking a gamer friend of mine here in Tokyo why the Xbox wasn’t popular and he said that it was just too bulky for the amount of limited living space the average gamer here has.

For the first few generations at least a lot of the parts in the iPhone were Japanese and if Sony or someone like them had had the vision they could have built it, but it took Steve Jobs who truly was a visionary, to build it. Of course, it’s well known that he was strongly influenced by Japanese design sensibilities

What you describe is textbook. Since Japan prices exports in USD it is clear a weak dollar reduces Yen profitability which leads to production cutbacks and wage suppression.

What is surprising is that the demographic downshift in Japan and Italy and Germany is biting but real wages are not increasing. Labour shortages are not reflected in wage inflation. It is true high taxation at low incomes makes it hard to obtain real net increases so many opt into the Black Economy or go for reduced hours/increased leisure which may be the same thing