Western economists and financiers have so regularly predicted a crash or zombification outcome to China’s spectacular run of growth that it’s too easy to dismiss stories about deflation risk as yet more Chicken Littledom. But that would be a mistake. The warning sign this time is coming not from tea-leaf reading prognosticators but the domestic investor dominated, very large and therefore not manipulable Chinese government bond market. Its plunge in yields to deflation-warning levels is a sign of profound concern about growth prospects. And if actual or borderline deflation becomes entrenched, it’s hard to reverse.

Before we turn to the evidence, a wee bit of background. As much as inflation-whacked Americans might find it hard to believe, deflation is far more destructive than inflation. Falling prices across most of an economy signals weak demand. That can easily become self-reinforcing. Businesses and consumers put off spending because they aren’t certain if and when things will pick up. Continued diminished outlays results in less hiring and eventually reductions in hours and layoffs, producing yet more belt-tightening. A trend of declining prices leads directly to even more savings. After all, if you don’t buy something now, it will probably be cheaper later. Since future dollars are worth more than present dollars, prices of risk assets like stocks and housing tend to fall, making those holders feel poorer, once again whacking spending.

And a further accelerant is debt dynamics. As the general price level falls, the real value of debt increases. That in combination with a flagging economy means more business failures, and so with that, less commercial spending, more job losses and a further contraction in economic activity. See Irving Fisher’s classic paper for details.

Chinese economic statistics are often criticized as unreliable. For instance, Michael Pettis has explained long-form how their GDP figures are not comparable to those in the West.1 When I started this site, analysts would regularly say they did not use reported GDP but instead uses electricity consumption. A few years later, for reasons I don’t recall clearly, those figures came to be regarded as fudged.

So one reason for a pessimistic bias among China commentators has not been Orientalism (although that plays a role) but that key Chinese data really does have a bias, much more than Western stats, to exaggerate, so that when any negative figures or factoids appear, they are deemed as “truer” due to looking like admissions against interest.

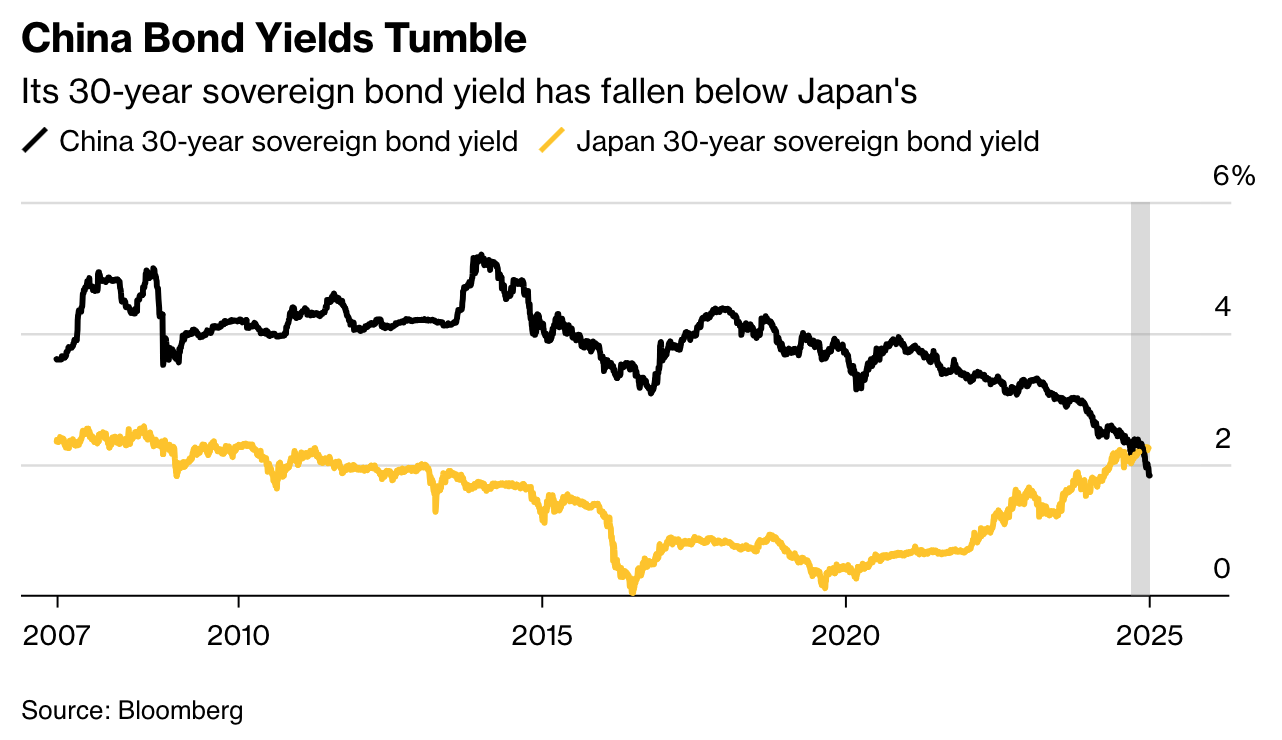

To the bond market warning sign, and then other reasons to think that deflation and zombification risk in China is real. From Bloomberg:

Investors in China’s $11 trillion government bond market have never been so pessimistic about the world’s second-largest economy, with some now piling into bets on a deflationary spiral mirroring Japan’s in the 1990s..

The plunge, which has dragged Chinese yields far below levels reached during the 2008 global financial crisis and the Covid pandemic, underscores growing concern that policymakers will fail to stop China from sliding into an economic malaise that could last decades….

In a sign of how seriously investors are taking the risk of Japanification, China’s 10 largest brokerages have all produced research on the neighboring country’s lost decades….

While an echo of post-bubble Japan is far from certain, the similarities are hard to ignore. Both countries suffered from a real estate crash, weak private investment, tepid consumption, a massive debt overhang and a rapidly aging population. Even investors who point to China’s tighter control over the economy as a reason for optimism worry that officials have been slow to act more forcefully. One clear lesson from Japan: Reviving growth becomes increasingly difficult the longer authorities wait to stamp out pessimism among investors, consumers and businesses.

“The bond market is already telling the Chinese people: ‘you are in balance sheet recession’,” said [Richard] Koo, chief economist at Nomura Research Institute. The term, popularized by Koo as a way to explain Japan’s long struggle with deflation, occurs when a large number of firms and households reduce debt and increase their savings at the same time, leading to a rapid decline in economic activity…

The problem is that the policy prescriptions so far haven’t been nearly ambitious enough to reverse falling prices, with weak consumer confidence, a property crisis, an uncertain business environment combining to suppress inflation. Data due Thursday will likely show consumer price growth remained near zero in December while producer prices continued to slide. The GDP deflator — the broadest measure of prices across the economy — is in its longest deflationary streak this century.

One issue with the latest Chinese stimulus approach is that China has been trying to shift from growth via debt-fueled investment in real estate to tech industry growth. The problem is that this still amounts to focusing on increasing production as opposed to consumption. Even though many Twitterati and reader pooh-pooh the notion that there is such a thing as overinvestment, have a look at the railroad industry in the mid-late 1800s which was rife with overbuilding and bankruptcies, or now, the office space market in most US cities, which is in considerable overcapacity due to work at home. Too much output in relationship to demand for product and services results in aggressive competition for the existing buyers and so either price cutting or covert discounting via freebies. Enough of that and you get capacity cutbacks via operation closures and/or bankruptcies. The output level (ex continuing government subsidies) eventually contract to a level that can be supported by sales volumes.

But China’s policy-makers seem to have a case of having changed their minds but not their hearts. Even though many agree that the Middle Kingdom needs to shift to a more consumer-driven economic model, China recoils from taking the big step to getting consumers to save less, which is stronger and more extensive social safety nets. Consider:

To promote common prosperity, we cannot engage in ‘welfarism.’ In the past, high welfare in some populist Latin American countries fostered a group of ‘lazy people’ who got something for nothing. As a result, their national finances were overwhelmed, and these countries fell into the ‘middle income trap’ for a long time. Once welfare benefits go up, they cannot come down. It is unsustainable to engage in ‘welfarism’ that exceeds our capabilities. It will inevitably bring about serious economic and political problems.

— Xi Jinping

If anything, China’s meager social safety net has become more threadbare of late. From the Hudson Institute:

Local governments are responsible for more than 90 percent of China’s social services costs but only receive about 50 percent of tax revenues. For decades, they have relied on land sales and related real estate revenues to meet their budgets, but both sources have declined precipitously as the housing boom has reversed course. According to the Rhodium Group, more than half of Chinese cities face difficulties paying down their debt, or even meeting interest payments, severely limiting their resources for social services. China’s total debt levels are estimated to be around 140 percent of GDP, limiting budget flexibility for supporting social services.

While the bond market data is arresting, other statistics point in the same direction. Youth unemployment is high, reported recently at between 16% and 19% until China stop publishing that date series. Prices have fallen for six consecutive quarters. One more would put it at China’s modern record, during the 1990s

Asian crisis.

Bloomberg, in a different story right before year end, noted:

Prices rocketed in the US and other big economies when they reopened after the Covid-19 pandemic, as pent-up demand coincided with shortages in the supply of many goods. Predictions the same would happen in China proved to be wrong. Consumer spending power is weak and a real estate slump has dented confidence, holding people back from buying big-ticket items.

A tightening of regulations on high-paying industries from tech to finance has led to lay-offs and salary cuts, further dampening the appetite for spending. A policy push to develop manufacturing and high-tech goods led to increased production, but demand for the goods has been weak, forcing businesses to mark down prices….

Transport has been the biggest drag on consumer prices lately, driven mostly by falling car and gasoline prices. Carmakers including BYD Co. have asked suppliers to cut prices, signalling an intensified price war in China’s auto-market. For the broader economy, real estate and manufacturing are the sectors that recorded the deepest contraction in prices in the first three quarters of 2024, based on an industry-level gross domestic product deflator calculated by Bloomberg. A persistent property bubble has led to a housing inventory glut, while the government’s support for manufacturing — from cheap loans to favourable tax policies — has increased the supply of goods that consumers are hesitant to purchase.

These and other articles have pointed out that China’s recent stimulus measures are weaker than past ones. They are also directed to consumers only to a limited degree, with some aid to students and the poor, subsidies for auto and appliance purchases, pressure on banks to lend for the purpose of completing stalled developments, and exhortations to local governments to purchase unsold residential units and convert them to public housing (the latest stimulus package does include local government debt relief, so they might have enough budget room to do that to at least a degree). The Bank of China has also been cutting rates over the last two years. But as we have repeatedly pointed out, putting money on sale does not lead businesses to invest more unless their business is leveraged speculation (like financial traders, banks, private equity and often real estate developers). Enterprises will borrow to fund growth if they see opportunity; the cost of money can be a constraint but cheap money isn’t sufficient cause in and of itsself for most managers to commit to an expansion plan. As we saw with ZIRP, the side effects of a long period of too-low interest rates is income inequality and a painful exit, since at very low rates, the financial asset price whackage of rate increases is much greater than at “normal” levels (say 2% or higher policy rates).

So far, China has done an excellent job of escaping the usual fate of economies that move from being export and investment-lead to consumption-lead, that of suffering a serious financial crisis. Has its luck finally run out?

_____

1 The eye-catching start to his January 2019 article:

The Chinese economy is not growing at 6.5 percent. It is probably growing by less than half of that. Not everyone agrees that the rate is that low, of course, but there is nonetheless a running debate about what is really happening in the Chinese economy and whether or not the country’s reported GDP growth is accurate….

….when you speak to Chinese businesses, economists, or analysts, it is hard to find any economic sector enjoying decent growth. Almost everyone is complaining bitterly about terribly difficult conditions, rising bankruptcies, a collapsing stock market, and dashed expectations. In my eighteen years in China, I have never seen this level of financial worry and unhappiness.

Should “inflation” in the first paragraph be “deflation”?

I don’t think so. But in the second paragraph:

Deflation means future dollars are worth more than present dollars.

Ooops, bad drafting, fixing.

So, it looks like the Ivy League will NOT be offsetting the drop in the US college student population with high paying Chinese student tuition? Hmm. What goes around comes around.

I will wait a year or two to see how this turns out.

The low yield may reflect a flight to safety since RE is no longer a reliable investment vehicle. The Chinese government may prefer the lower yields to encourage more money to flow into “productive” areas such as NED, automation, and high tech R&D. Low interest also makes BRI projects much more affordable for the counterparty.

The Chinese invest for the long term, so big tech heavy CapEx expenditures that Xi has been championing won’t produce income for several years. The CapEx is also occurring in secondary and tertiary cities where land and labor costs are far lower but logistics has caught up. People in Shanghai, Beijing, or Shenzhen won’t see this.

China will have more levers than Japan for dealing with deflation. The US cannot force them into Plaza Accord II so currency deflation is always an option, and they’re already far and away the price (and increasingly, quality) leader for most kinds of manufacturing. They’re also not limited ideologically to market solutions, so they could pursue more unorthodox approaches to stimulate the economy if it becomes necessary.

Ugh, meant “currency devaluation”!

Comparing China to Japan directly overlooks what the US did to deliberately make Japanese industry uncompetitive and build up competitors to Japanese cutting edge industries such as chip fabrication. I believe TSMC and Samsung both got their start in chip fab with the US program to build competitors to Toshiba and Sony.

This isn’t to say China won’t have its own challenges, but it will be the sort that faces a country that the US recognizes as an existential enemy, not an occupied satrapy. So far the various US sanctions have backfired spectacularly, but I’m sure DC will keep trying

Excellent point. The term “Japanification” and the historiography of Japan’s stagnation have from the beginning been designed to obscure that it was an engineered and imposed process. The US thought Japan was growing too fast and ordered it to commit economic suicide by allowing the price of its currency to double through the Plaza Accord.

In no way was it a question of Japan running into some kind of natural barrier for its growth. The pretense then continues that the “lost decade” (which turned into lost decades) was somehow an organic phenomenon and that there was a real estate bubble that just happened because the Japanese went crazy.

The US cannot in the same way order the Chinese to commit economic suicide, as in for example doubling the value of its currency to gut its exports. The Chinese will laugh at whoever comes to demand that just as they laughed at Janet Yellen when she came on her little plane to beg them to buy more US Treasury bonds right after talking (the US elites always seem to forget that the rest of the world can read their newspapers and watch their TV channels) about how China needs to be smashed to pieces because it’s a threat to America.

And likewise, Trump can put all the tariffs he wants on China, but since American industry is gone, with all its factories, its skilled labor, its education system, its competitiveness in all respects (such as the cost of living of its labor), its demographics, its infrastructure and so on, the increased import costs just will be passed on to the American consumers.

Just like last time (even when we don’t count the goods that were rerouted through Mexico), China’s trade surplus with the US will bounce back almost immediately to its previous levels and then hit new record highs. And Trump (just like Biden, who continued and doubled down on Trump’s policies) will look like the chump that he is.

Edit: After reading your original reply I realize now I’ve largely just repeated a lot of points you had already made. But anyway.

Lol, thanks for this, you definitely gave me more points for thoughts, especially on how US’s hollowed out industrial base (and increasingly shaky grasp on military hegemony and dollar dominance) really changes its available options for dealing with the China threat.

The other thing I’ve noted in the few months of following this Inside China Business guy https://youtube.com/@inside_china_business?si=lXC5Ke577fq2nks7 (mostly to cheer me up after another day of seeing the Gaza genocide reach new depths in depravity), is China’s willingness to help primary producers move up the value chain. It’s not hoarding lucrative business opportunities for itself.

There’s a lot of Western projection of their historical norms for far flung imperialism and depredations, onto what the Chinese are doing. Will the Chinese turn evil and oppressive when it’s their turn at the top? It’s possible but based on their history, it seems to me highly unlikely. Foreign wars are very costly and saps a country’s strength. Expansionist empires are inherently unstable. The only reason Americans keep at it is because our controlling oligarchy happens to be made up of weapons merchants and others who benefit from exploiting a trotten down RoW.

The only reason normal non-militarist-imperialist (like US, Israel, and what the French did to Libya)countries do it is to fight off existential threats on their borders.

No, this is false but people like Jeffrey Sachs, whose knowledge of Japan I have found to be sorely wanting, propagate this myth.

I was working very closely with Sumitomo Bank, then the second biggest company in the world by market cap, and the Japanese analogy to Citibank, first as a consultant, later as the head of their mergers & acquisitions department, from before when the Plaza Accord was implemented (1983) to 1989. I was regularly in contact with domestic (as in with Japan) branch heads. Because I was hired in the Japanese hierarchy (the first Westerner given such status), I was treated as a real insider.

The culture at Sumitomo (as an Osaka bank, very different from Tokyo based banks) was very profit minded and communications were extremely direct by Japanese standards.

The Plaza Accords were very shortly reversed by the Louvre Accords of 1987. The yen did a big overshoot on the upside and so that was significantly undone by the later deal.

If you look at Japanese GDP figures during this period, growth was barely dented even in 1986 and went back to trend.

I heard no, and I mean absolutely no, complaints about growth issues in the economy either within the bank or from the many clients I met. Indeed, many were very eager to take advantage of the higher yen and invest overseas, which they never would have considered if they were having difficulty.

That is not to say the US didn’t have a hand in the Japanese bust, but most wildly misassign the cause, and I doubt any policy maker in the US anticipated what would happen.

The US forced rapid deregulation upon Japanese banks. Despite Japanese prowess in manufacturing, and good OPERATIONAL control of banks, they were primitive in risk management. I had to help them devise their first remotely adequate asset-liability management systems as a consultant. They were nearly entirely non-users of basic finance concepts like discounted cash flows.

This was like taking a drayage company, telling it that it was really in the transportation business, and giving it fully fueled 747s to fly. A crash was inevitable.

These clueless banks started speculating in derivatives like the newly created Japanese warrant market. They were also lending 100% against the value of Japanese central city land (the value of commercial buildings was all land) when those values were fictive. Land and buildings never traded. No one would ever sell land. It would be like selling your children. It would be done only in the last stage of the liquidation of a business, if then. Oh, and the taxes on any such sales were punitive.

What ‘really happened’ in Japan?

“Michael Oswald’s film “Princes of the Yen: Central Banks and the Transformation of the Economy” 『円の支配者』reveals how Japanese society was transformed to suit the agenda and desire of powerful interest groups, and how citizens were kept entirely in the dark about this. Based on the book of the same title by Professor Richard Werner, a visiting researcher at the Bank of Japan during the 90s crash, during which the stock market dropped by 80% and house prices by up to 84%. The film uncovers the real cause of this extraordinary period in recent Japanese history. ”?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p5Ac7ap_MAY

Werner’s other book, with a more pointed title and published in Japanese was:

Why the Japanese Economy was Killed [なぜ日本経済は殺されたか] (2003)

Having read the longer Princes of the Yen and seen the film, I would be curious to hear what others here think about its argument. As I understand it, one of the main claims is that the asset bubble was in effect a deliberate policy undertaken by the BoJ, as they relaxed a formerly very strict regime of capital allocation (Werner describes this in detail), and allowed poorly managed, high-risk loans (basically, speculation on real estate), i.e., something like Yves describes above. On Werner’s account, the broader aim was a structural transformation of the Japanese economy, which I guess you could say has happened, though it doesn’t look very pretty. Werner speaks Japanese well, and had a research position at the BoJ for part of his years in Japan. Thus, I think we could say Werner had something closer to an inside view of BoJ policy, and this was the basis for his argument.

You may have read him – Alex Kerr in the book ‘Lost Japan’ has a similar story in the 1970’s and 80’s in Japan about the cluelessness of Japanese finance (in his case, the construction industry) in pricing in risk to any investment. If you’ve gone through an entire generation of uninterrupted growth, its all too easy to ignore what seems obvious to those who have survived booms and busts.

Every economic crash or decline has its unique characteristics, but so often, the underlying processes are very similar, as Minsky described. The Japanese crash was not in this sense in any way unique – almost all fast growing catch up economies have gone through it at some stage, including the US (specifically, before the much ignored ‘Great Depression’ of 1873 to the 1890’s). Sometimes countries get lucky for a variety of reasons (ROK in the 1990’s), but most don’t (Brazil and Argentina in the mid 20th Century, for example).

If there is one thing worse than deflation, its deflation with food price inflation, and at the moment this is a growing problem in China. The overall domestic economy has been stalling (relative to overall GNP growth and export growth) for a decade, arguably more. Youth unemployment right now (so far as can be judged from available statistics) isn’t far off the rates seen in southern European countries over the past decade and a half.

The potential Japanification of China has been discussed in Chinese sources since I first got interested in this, in the 1990’s. From the 1970’s onwards China had intensively studied developing country models, and of course Japans near-death experience in 1990 caught a lot of attention among Chinese economists. But learning lessons and applying them can be two different things. As Minsky and others pointed out, there is an inherent logic to upward swings in economies (and this applies to countries undergoing ‘catch-up’ growth as much as it does to the regular economic cycle) which encourages excessive risk taking during the ‘up’ swing – and China has had what amounts to a 3 decade or more period of more or less uninterrupted growth (even the 2007 Crash had a minimal impact thanks to an enormous fiscal boost by Beijing). Just to give one little factoid about Chinese investment levels – there are now approximately 60 major car brands in China, at least half of which are financed directly or indirectly by local governments at different levels. BYD and Geely may triumph over existing legacy brands, but one can only wonder at the financial carnage that will occur when the other 50 or so companies start fighting over a diminishing number of consumers.

Although it is the case study that most people know about, the ‘lost decade’ for Japan was not unique – it is actually the norm for fast growing economies since 19th Century. While each one had different reasons, a wide variety of export led fast growing countries have hit an apparent ceiling just as they approach ‘catch-up’ with their more developed rivals (the so called ‘middle income trap’). There are plenty of competing theories about this, but a common thread is that the economic policies of a ‘developed’ country have to be very different from a ‘fast catch up’ country. Managing that transition is very difficult and painful. China is discovering this the hard way.

I think a financial crisis is unlikely, simply because Beijing has too many policy instruments available to stop one. But that’s not necessarily a good thing. If you control the banking system, you can play musical chairs with balance sheets pretty much indefinitely (as Japan has been doing, and is still doing), but in the end someone pays the price for huge overinvestment without returns, and its usually whoever has least political leverage (i.e. ordinary people).

Just on a point on using energy as a proxy for economic growth. It usually is a good proxy, but at crucial stages, the links between growth and power use (specifically electricity use) can break down. One is when governments are focusing an enormous amount on energy intensive sectors of the economy (as is happening right now in China, although its hard to quantify the effect). So while growing energy use may indicate a stronger economy than the sceptics think, its not a given. A particular issue with China is that the reluctance to shut down older inefficient government owned industry even when they’ve opened up gleaming new super efficient plant means that investment is adding on, rather than replacing, older factories.

The other problem China faces is that if its growth stalls, its at a lower level of wealth and development than Japan, ROK, Taiwan. All four countries are facing similar problems of demographic decay and export dependent models with weak internal demand (or put another way, they are desperate for the US to keep buying their goods). But China is facing them at a lower level of economic development – which may encourage Beijing to double down on existing models (which is what they’ve been doing for 2 decades now).

Thanks for this thoughtful reply.

Regarding food prices, that’s not what this guy is saying – https://youtu.be/7D6qu-8n7Iw?si=2BUM6eMc4BTcFDlb

I have a friend who just came back from a vacation to Kunming and raved about the low prices for very high quality accommodations and food. I was paying more at mediocre restaurants for similar dishes 20 years ago. He’s from Hong Kong and travel to HK/TW/ML at least once a year and usually more often. Bertrand Arnaud recently took a trip to Sichuan and also noted that food prices were quite low for Michelin level quality. The quick growth of end to end distribution logistics directly between producer and seller and buyer seems to encourage more efficient pricing.

I don’t get the sense that there are still lots of lumbering old SOEs out there. Everything I’ve read so far suggest that Chinese competition is very cut throat and constantly innovating just to stay on the game. Even local government officials who manage investment portfolios have to keep up or risk getting fired for poor performance.

What you said might make sense 20 years ago, but doesn’t match what China is. Still far from perfect but China most definitely isn’t doing the same thing it has been doing for the last 30 years. It’s dramatically moved up the value chain for production, the young people are physically different and far more polite and educated than they were 30 years ago, the infrastructure and air quality are way better. Housing went from being the key economic driver to being something handed over to local government management for the public good. There’s enough quantitative change to accomplish serious qualitative changes – it’s way safer, more orderly, more polite, and more pleasant than it was 15 years.

I was referring to the price ordinary Chinese pay for groceries, not Michelin grade restaurants or places business travellers go. The latter are excellent value outside the main Chinese cities, but that’s as much due to intense competitive pressure as anything else. You’d really have to question why upmarket restaurants like that are getting cheaper when the country is getting richer in GDP terms.

Food prices have been trending slightly above overall inflation for the past six months now, although not so much as to cause popular discontent. But there are fears about even mild price rises due to various flu (pigs and chickens) – even very low food inflation is a big problem when other products are in deflation. The point I was trying to make is that when an economy is in deflation, even very small price rises in necessary consumables like food has an oversized impact on peoples ability to spend money. Deflation is almost always the result of excessive capacity of manufactured products – its rare that the price of food follows it downwards for obvious reasons.

So you would admit that Chinese food inflation is minimal thus far, then why talk about it for China when the US and Europe are dealing with far more dramatic food price inflation?

I referenced the restaurant pricing because I got more detailed looks of the dishes and prices, and both happened in the last few months. I do personally know a number of people living on mainland China and follow others in Twitter. I’m not aware of anyone complaining about food prices and comments for the last two years are more about how everything is on sale now (but that Shanghai bank manager just got his salary cut by half…) and tourist spots are quiet and deeply on sale outside of major holidays. So I see some pain on the higher end and in coastal cities, but these people have typically done very well in the last 20 years and can afford to take the hit.

I can’t think of anyone in China who would be unable to manage a temporary spike in food prices unless it was very extreme indeed. A primarily rice based diet means that if the other foods get more expensive, you end up just eating more rice. I remember when at the height of foot and mouth disease, pork was going for around $10 US/Jin, at a time when people had a lower income. They just had fewer pork dishes, like vast majority of the population did before 1990.

Food prices are precisely where Chinese planners want them to be, which is 1% higher in November 2024 than in November 2023. Chinese regulates food prices, just as was begun by Franklin Roosevelt with the New Deal, to insure enough gain for farmers to continually increase production. China also keeps energy prices for farmers low during planting and harvesting times.

Farm family incomes have for years been increasing faster than urban family incomes, though rural income level are still lower than urban.

For years, rural economics are “first” planned.

Thanks, PK. This is veering slightly, but since we’re on the topic of Japanification and the lost decades, and since you point out the difficulty of transition out of high growth, how do you see the roles of the Plaza Accords and changes in BoJ policy on lending (what Werner calls “window guidance”) in the 1980s?

Interesting that “middle income trap.” I’d like to hear more about the dynamics. When I was at Uni we were presented with Rostow’s ‘Stages of Economic Growth’. Of course the primary presumption was the ‘take-off stage’ wherein the LDC (actually, UDC in those superior days) met the industrial and other sector requirement to enter the stages of high consumption and economic security. The first tip-off for me about this liberal nonsense was when neither Brazil nor Argentina ever took-off.

“China has done an excellent job of escaping the usual fate of economies that move from being export and investment-led to consumption-led, that of suffering a serious financial crisis.”

Forgive me, but after carefully reading the essay twice, I think China is developing splendidly. China has had to confront many years of American-Western efforts aimed at undermining Chinese development. Chinese economic policy has been continually criticized by prominent American-Western economists since “1980” but look to the result:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1pMR0

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for China, United States, India, Japan and Germany, 1977-2023

(Indexed to 1977)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1pMQV

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for China, United States, India, Japan and Germany, 1977-2023

(Percent change)

But isn’t the Japanification of all economies inevitable if eternal growth is impossible?

Ah, an excellent point. I will have to ponder further but think you are right, at least when an economy gets large relative to the global economy.

Or, maybe years of over-investment (and under-consumption) eventually create a debt-overhang that sucks up economic resources and energy. The interesting thing that you wrote about above…land and buildings in Japan that never sold…implies heavy speculation and the eventual debt over-hang precipitating an Evergrande or a Creditinstalt. The Japanese never wrote off these monster debts leading to decades of debt deflation. Interesting to see what the PRC (or the CCP) do about the demise of their own debt monster that has put the screws to millions of ordinary Chinese, and who are facing a wipe-out of their investments. Can they get the Jubilee started…but, at the same time can they bail-out Mr. & Mrs. Jo Schmoe

It sounds as if you might be somewhat misconstruing what I said.

Most of Japan is extremely densely built due to how much of the country is mountainous. The EXISTING properties were valued at land value. Corporations could borrow against that at banks like Sumitomo for 100% of the land value. This was not speculation in the normal sense.

Having said that, Japan also allowed very high margin borrowing against stocks.

“The potential Japanification of China…”

For the Chinese, Japan as a country means invasion in 1931, beginning World War and resulting in the deaths of some 20 million Chinese. While many Japanese have individually atoned, the Japanese government distressingly has never done so.

Economically, China in GDP is more than 5.7 times the size of Japan and growing far faster and more stably. China could never become Japan:

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/weo-report?c=223,924,132,134,532,534,536,158,546,922,112,111,&s=PPPGDP,PPPSH,&sy=2000&ey=2024&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1

2024

China ( 37,732)

Japan ( 6,572)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1t5Ok

August 4, 2014

Real per capita Gross Domestic Product for China and Japan, 1977-2023

(Indexed to 1977)

@CA I think you are mistaking a cold look at reality with an attack on China. Personally I believe that there’s of course a limit to Chinese growth. When Mahatma Ghandi was asked when India would be as wealthy as GB he answered: Hopefully never. If 50 Million Brits devour the world like locusts what if 500 Million Indians try the same? So yes, of course China cannot expand forever and it seems she has reached some treshold. Not surprising that this crisis resembles the Japanese crisis. It is after all a very similar culture.

I believe though that China has a big advantage going forward. It still has the knowledge of traditional agriculture. The mistake of the West has been the application of the industrial mindset to the soil. We are putting so much fossil input into our production of food (fertilizer, pestizides, tractor fuel a.s.o.) that we use more energy than we harvest. The numbers are staggering.

In 1985 I studied in China and I learned something really astonishing: China had the least farmland per person but the highest harvests per acre. Being then still pretty much cut off from world markets they managed that largely without the use of artificial fertilizer et al. Agri experts from the West sniffed their noses at the Chinese as their “productivity” was very low. “Productivity” of course meaning output per agri worker. This kind of mindset still rules in the West and we are already getting the bill regarding health, soil degradation a.s.o. We will be forced to return to a different mindset. Especially as the rest of the world industrializes and fossile inputs will become more and more expensive in terms of trade. China is still following the Western playbook in agriculture but she will turn around out of necessity. And she will be able to as the knowledge is still there. We are to far into the cul de sac and will have a much harder time to do the same. On top we are losing our industry to China and it is therefore not hard to foretell that China will have both an industrial sector when the environmental shit hits the fan and a sustainable agricultural base if she so chooses. China is the future.

“I believe though that China has a big advantage going forward. It still has the knowledge of traditional agriculture. The mistake of the West has been the application of the industrial mindset to the soil…”

A brilliant comment that should be extended over time.

China is expanding arable land through the country, re-developing traditional seed that grows well in and actually revitalizes less fertile soil and is adaptable to newer climate conditions. Agricultural productivity is increasing steadily in organic ways. Also, China has been investing about $150 billion yearly! in water conservancy.

Crop storage has been modernized and expanded, so that food surplus of 2 years is standard.

Then too, China in working on agriculture in the global south.

This is very encouraging news. I had no idea.

https://english.news.cn/20250107/336db0a6432943d9b21ede73bfd67092/c.html

January 7, 2025

Chinese scientists unlock key advances in sugarcane genomics

NANNING — A Chinese research team from Guangxi University has successfully decoded the genome of the modern cultivated sugarcane variety Xintaitang No. 22 (XTT22), shedding light on the highly complex allopolyploid genome of sugarcane and its evolutionary mechanisms.

Sugarcane plays a vital role in the production of sugar, alcohol, and bioenergy, offering substantial economic and agricultural value. XTT22 was once the leading sugarcane variety in terms of planting area in China for 15 consecutive years. More than 90 percent of the country’s fourth and fifth-generation sugarcane varieties were developed using it as a parent…

The research * was recently published in the journal Nature Genetics.

* https://www.nature.com/articles/s41588-024-02033-w

I have something completely different in mind. What you are presenting here is the same we have in Western agribusiness. I am talking about the agricultural revolution during the Quing dynasty. It is very little studied and much less understood how China managed to triple her population without resorting to any of the “modern” western methods. To give you a very simple example of what I mean. In wet rice planting you insert fish into the rice pond and surround the pond with Mullberry trees. In the Mullberry trees you have silkworms, that release their shit into the water, which is eaten by the fish which fertilize with their digestions the rice. In the end you have fish, silk, mullberries and rice. What sounds so simple is in fact really difficult to put into practise and demands a lot of labour. You can´t do that with machinery but you get yields higher then anything achieved in the US or in Italy in the delta of the Po river.

And there ‘s much more. China has turned away from these ancient practises and the current goverment has gone all in on western style “productivity”. We in the West had similar – although not as elaborate – traditions which we foresook in the name of “efficiency” and “prodcutivity”. The hands on knowledge of these things is mostly lost except in a few pockets of Eastern Europe such as Poland. In China though the transition is very recent and not yet complete and they can still return and of course improve on it. The end result will probably a large part of the population working the land and a restricted urban population engaged in industry.

[ What you are presenting here is the same we have in Western agribusiness. I am talking about the agricultural revolution during the Quing dynasty. It is very little studied and much less understood how China managed to triple her population without resorting to any of the “modern” western methods. To give you a very simple example of what I mean. In wet rice planting you insert fish into the rice pond and surround the pond with Mulberry trees… ]

What the Chinese have been doing is examining plantings over centuries to understand just the crops that were planted, how crops were planted, and the success of the harvests over time. Basic grains have been traced over centuries, not just in China but by Chinese scientists through Africa. The Chinese understand how African millet crops become wheat and how wheat has changed since Egyptian plantings.

Potato crops have been traced for centuries, from South America to Europe and North America, and Chinese scientists have brad potatoes that produce seeds rather than only tubers for reproduction.

Good grief, look to how rice in Madagascar has become a revolutionary crop with Chinese development…

OK, no sweat. Sure Chinese scientists have some great developments along the lines of western plant science. What you don´t seem to understand is that the problem of industrial agricultural is holistic and has nothing to do with developing new and better crops. New and better crops without thinking through the whole system of pest control of feedback with different plants, of nutrition depleting of the soil a.s.o. is what got is into this mess in the first place. By the way: Chinese agricultural practices in Tibet and Inner Mongolia are catastrophic. I am confident though that China will revers course. And she can whereas for us it is much harder.

BY the way, before I forget: the catastrophic impact of Chinese agricultural practises on the Tibetan plateau and in Inner Mongolia is well known among Chinese soil scientists. They just hide their findings in obscure journals as it is not politcically opportune at the moment. Their time will come though.

Potato plants have for a long time produced seedbearing fruits, generally called “seed balls”. ( I tried image-searching for potato seed balls but most of the images that come up are for a different sort of seed balls known as Fukuoka seed balls).

Here is a little article about potato seed balls with a picture.

https://gardeningwithallie.com/why-do-my-potato-plants-have-balls/

Potato and tomato breeder tom Wagner has been crossbreeding various varieties of fruit-bearing potato plants for decades to achieve some of the varieties he has achieved. He used to have a catalog but now I think he releases new varieties through more established companies. Here is his blog.

https://tater-mater.blogspot.com/

Potato true-seeds have long been known about.

>>> Its plunge in yields to deflation-warning levels is a sign of profound concern about growth prospects.

The flip side is that there is ample demand for PRC government debt with the funds used for more transformational investments.

The US/EU used the funding from zero, near-zero 30-year bond rates to plug short-term spending needs. Can China do better?

PRC sells 500 billion USD-equivalent of debt, buys $500 billion of friends and influence at home and around the world with potentially generationally transformative projects.

First, China is a sovereign currency issuer. It does not need to issue bonds to spend.

Second, any Chinese bonds or Chinese currency net spending can only be spent in China. To spend abroad, it must sell its currency and buy the foreign currency.

The nations that have used the post-WW2 fast catch through exports model have found it extremely difficult to shift to an economy centered around domestic consumption. In Japan, certainly special interests built up around exports and have been difficult to dislodge. But I think deeper cultural factors also are at work. Decades of so strongly emphasizing production over consumption changes the culture.

I thought that the power and comparative unity of the Communist Party of China might allow it to knock heads among those special interests, but they have failed to do so at least since the 2008 global financial crisis. Part of that is that the heads that need knocking are key parts of the Communist Party itself, but I suspect that part of it is that China looks at consumption-centered countries like the US and the EU and is repulsed.

It is true that China is not as developed internally as Japan and South Korea and Taiwan were when they hit the wall, but it has a much larger share of world production, so there is much less room to twist aside a bit and hit the wall with a glancing blow.

Heaven help us all.

Please notice that China’s trade surplus is quite moderate, resulting from Chinese investment and productivity gains and in no way meant to exploit. Also, remember that Western countries have for years sought to stop China from buying a range of products:

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/weo-report?c=223,924,132,134,534,536,158,922,112,111,&s=BCA_NGDPD,&sy=2000&ey=2024&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1

October 15, 2024

Current Account Balance as percent of Gross Domestic Product for Brazil, China, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Japan, Russia, United Kingdom and United States, 2000-2024

2024

Brazil ( – 1.7)

China ( 1.4)

France ( 0.1)

Germany ( 6.6)

India ( – 1.1)

Indonesia ( – 1.0)

Japan ( 3.8)

Russia ( 2.7)

United Kingdom ( – 2.8)

United States ( – 3.3)

“To promote common prosperity, we cannot engage in ‘welfarism.’…”

Anyone speak Mandarin? It looks like the Xi quote was machine-translated from the primary source here >>>> http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2022-05/15/c_1128649331.htm

I wonder how a human interpreter would phrase Xi’s Chinese remarks into American English as contemporary American English has (collectively) imbibed a negative connotation to “welfare”

促进共同富裕,不能搞“福利主义”那一套。I am not well versed in political terms, but the two big phrases there are 共同富裕 and 福利主义. The former refers to the so called common prosperity, one of the political slogans of the Communist Party with the goal of bolstering social and economic equity. This term has existed since the era of Chairman Mao, and in practice seems to be the equivalent of the New American Dream i.e. you’d better be asleep to believe in it. With the opening of the economy, China’s Gini coefficient naturally climbed, and peaked sometime in 2009, it has come down since then but still around the same level of that of the United States …. for a socialist country.

The word 主义 in 福利主义 can be translated as -ism, for example capitalism in Mandarin is 资本主义 ( 资本 is capital ). The word 福利 means benefit, welfare, etc. English is not my native language either, but if I have to translate that sentence that you pointed out, then perhaps it’s going to be something like this: full blown social security will not be a pillar of common prosperity or maybe ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for common prosperity.

福利主义 does translate to welfare-ism. They don’t want to give direct handouts to people, even those perceived as being in need, because they’re afraid of breeding dependency and other negatives that westerners associate with welfare.

共同富裕 speaks to creating the conditions for everyone to have the ability to earn a good living. So building infrastructure to previously inaccessible areas, sending volunteer teachers from cities to remote village schools, and pushing for a coastal conglomerate to build factories in Xinjiang, would all fall under this approach.

Nah, “不能搞“福利主义”那一套” is mean to “多劳多得,少劳少得,不劳不得”

The more you work, the more you get; the less you work, the less you get; no work, no gain. This is a fundamental principle of China’s socialist system of distribution according to work(按劳分配).

Basically, the meaning of that sentence is that if you want to participate in common prosperity, you must make a contribution.

And it coexists with the social security system.

The distribution system in which distribution according to work is the mainstay and a variety of distribution methods coexist was established at the Third Plenary Session of the 14th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in November 1993. At this session, the Decision on Several Issues Concerning the Establishment of a Socialist Market Economy System was made. The decision detailed the personal income distribution system that is compatible with the socialist market economy system and put forward the basic principle of “adhering to the system in which distribution according to work is the mainstay and a variety of distribution methods coexist in personal income distribution”, thereby establishing the coexistence of various distribution methods with the distribution according to work as a long – term system.

reference: https://zh.wikisource.org/wiki/%E4%B8%AD%E5%85%B1%E4%B8%AD%E5%A4%AE%E5%85%B3%E4%BA%8E%E5%BB%BA%E7%AB%8B%E7%A4%BE%E4%BC%9A%E4%B8%BB%E4%B9%89%E5%B8%82%E5%9C%BA%E7%BB%8F%E6%B5%8E%E4%BD%93%E5%88%B6%E8%8B%A5%E5%B9%B2%E9%97%AE%E9%A2%98%E7%9A%84%E5%86%B3%E5%AE%9A#%E4%BA%94%E3%80%81%E5%BB%BA%E7%AB%8B%E5%90%88%E7%90%86%E7%9A%84%E4%B8%AA%E4%BA%BA%E6%94%B6%E5%85%A5%E5%88%86%E9%85%8D%E5%92%8C%E7%A4%BE%E4%BC%9A%E4%BF%9D%E9%9A%9C%E5%88%B6%E5%BA%A6

I hope this is OK to ask this question of anyone at NC or the Readership. I have wanted to read trustworthy information about China’s real estate crisis for years. Whenever I do a search, I get papers that seem to be gleefully reporting that the sky is about to fall on the Chinese economy, and appear to be narrative/propaganda. As this article explains, there are definitely legitimate issues that I would like to understand further. I have noted the links shared here but I would like a primer – if one has been written – article or book – that fairly explains what is going on, particularly in the real estate market (in layman’s terms).

Thank you in advance to anyone who responds.

” I have wanted to read trustworthy information about China’s real estate crisis for years…”

I suggest looking to Xinhua ( https://english.news.cn/ ) or CGTN. Here is my clumsily written summary:

What happened was that Chinese real estate came to be viewed not as simply offering places to live but as speculative investments. Private savings increasingly was being aimed at housing for the sake of capturing price increases. Chinese planners grew worried and President Xi announced a change. Real estate was to be for living in rather than speculating on.

The change in real estate purpose was announced, suddenly there was new built real estate that was not needed for living in, at least not for a while, and speculation stopped. That policy change left real estate companies with more apartments than could be sold. How to pay the debt for building was the problem.

Well, there have been debt defaults, there are vacant housing complexes and builders that met debt began to build only what could be readily sold for living in not speculating on.

Chinese policy makers are not about to change, but what is being done is to make sure real estate is affordable for living in. Change is coming, but slowly.

Meanwhile, China is a wildly rich country now and debt can be met. Planners stopped the bubble growth as necessary. The economy has become increasingly productive with productive investment beyond speculative real estate.

Thank you!

“Chinese planners grew worried and President Xi announced a change. Real estate was to be for living in rather than speculating on.”

This may sound naive, but I find it really impressive that President Xi is making decisions based on what is best for ordinary citizens rather than the high flyers. What a refreshing perspective!

BTW: Your “clumsily written summary” was very clear and helpful. Thank You

You can not find an serious and reliable article or book to ‘fairly explains what is going on’, because it is going on, maybe there’ll be some 5-10 years later, give some retros for this

As a Chinese, I can tell real estate crisis is never a crisis for China, but only a crisis for real estate market, ** so far **.

Many real estate investors suffered losses, a small number of homebuyers suffered losses, and it hurt the consumer and investment markets to some extent – when your assets are depreciating, you may reduce your consumption.

As for whether the crisis will spread and worsen, I think it mainly depends on the condition of major banks.

Currently, by my observation, it has reached its final stage. Some real estate developers are in a desperate situation and just about to go bankrupt, and the government has not provided them with relief (instead focusing on ensuring the delivery of pre-ordered houses), even though these developers appear to be “too big to fail.”

Modern China is such a young economy that I find your confidence based on the all of one real estate bubble in progress to be misplaced. I can see the effects here in Thailand. This year’s high season is very soft as is the real estate market, which has Chinese buyers as the most important foreign investor group. And it is the local governments, via local government financing vehicles, and their investors that are exposed. The central government kept tight controls on banks but then (this is a crude summary) let and even pressed the local governments to step up. So there’s a very large and not at all well understood shadow banking sector.

Japan, which had a simply ginormous commercial and residential real estate bubble, and a bit of a stock market bubble too, did not have an overt crisis when things started going into reverse in 1990. But after a few years of zombification, the authorities declared victory prematurely in 1997, which led to a series of bank failure. So the immediate test is not something like a bank run, but a failure of banks to clean up their balance sheets to lead to them keeping dud project and companies on life support and accordingly limit new lending.

https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/12/01/people-should-be-reading-adam-posen/

December 1, 2008

People Should be Reading Adam Posen

By Paul Krugman

Everyone’s looking back to the 1930s for policy guidance — and that’s a good thing. But we don’t have to go back that far to see how fiscal policy works in a liquidity trap; Japan was there only a little while ago. And Adam Posen’s book, * especially on, “Fiscal Policy Works When It Is Tried,” is must reading right now.

* http://www.petersoninstitute.org/publications/chapters_preview/35/2iie2628.pdf

September, 1998

Restoring Japan’s Economic Growth

By Adam S. Posen

https://www.piie.com/publications/chapters_preview/35/2iie2628.pdf

September, 1998

Restoring Japan’s Economic Growth

By Adam S. Posen

Fiscal Policy Works When It Is Tried

If the current Japanese stagnation is indeed the result of insufficient aggregate demand, what should be the policy response? Fiscal stimulus would appear to be called for, especially in a period following extended over-investment that has rendered monetary policy extremely weak. Yet the statement is often made that fiscal policy has already been tried and failed in Japan. Claims are made of variously 65 to 75 trillion yen spent in total stimulus efforts since 1991, even before the currently announced package. Both the Japanese experience of the late 1970s of public spending as a ”locomotive” to little-lasting domestic benefit, and the worldwide praise for government austerity in the 1990s, have predisposed many observers to dismissing deficit spending as ineffective, if not wasteful. Could there really have been this much stimulus effort having so little effect?

The reality of Japanese fiscal policy in the 1990s is less mysterious and, ultimately, more disappointing…

https://www.piie.com/publications/chapters_preview/35/2iie2628.pdf

Sorry, sorry, here is the correct reference link to Posen. The link was changed and I did not notice.

Interesting piece–illustrating the immense complexity that a more dirigiste approach entails for government managers.

The welfare-state skepticism by Chinese government was unexpected. Since the safety net is a form of insurance, the government might consider offering more generous safety-net terms precisely when the risk of needing it rises, in general, and in relation to certain activities (e.g., home & car purchases, domestic vacations) in particular.

While I’m always skeptical of spin that the “Chinese economy is screwed” in the Western press, it’s very possible that deflation really is setting in. What I find more interesting is the possibility that even if it’s 100% accurate, that may not mean the same thing in China that it means in many (most?) other countries.

Herbert Hoover is famous for his “purge the rot from the system” line when faced with the deflationary spiral that caused the Great Depression. Just a thought experiment though, what if there are a small set of situations where he would have been right? If despite the initial pain, the society and state was capable of actually using austerity as a decisive reset, instead of continually starving itself? All I would say is, if you’re willing to consider such a thing is possible, China would almost definitely be the one country to pull it off.

I won’t sound like a broken record on the whole “outwardly Confucian / Marxist, inwardly Legalist” theme, but China makes a lot more sense once you see it. China is a different culture too. AFAIK an ideological commitment to ease suffering or comfort the unfortunate or downtrodden (similar to Abrahamic religious mercy) has just never really been a thing there, and consequently neither are social welfare programs.

Whatever its sincerity about other aspects of Marxism, I do completely believe the Chinese government is smart enough to be very serious about internal contradictions. Beyond export-led development, I expect the government recognizes that industrial development of any flavor can’t keep going forever. If Yves’ thesis is true and this is a real deflationary spiral setting in, I could actually believe that China has decided the people can “swallow their bitterness” and is maybe the first government to unofficially commit to some form of controlled de-growth.

Is deflation really that bad? Everyone focuses exclusively on the demand side of things and develop their theory on that but it also involves a supply side, that being an increase in productivity.

Huh? That is nonsensical. The resulting slow or fast depression produces lower capacity utilization across most productive assets. Wages are the stickiest price, so they tend to fall last and slowest, meaning labor productivity does not improve or gets worse.

I know that we don’t trust Chinese GDP numbers because of the creative ways that they are calculated. But how about the US? In 2023 the US economy had real GDP growth of 2.9%. During the same year, the government deficit was $2.65 trillion (https://fiscaldata.treasury.gov/datasets/debt-to-the-penny/debt-to-the-penny ). That is almost a 9% deficit with 2.9% growth, or a net increase of liabilities of 6%. What would be the rate of growth without that huge government injection into the economy?

I want to touch on a topic not mentioned above, but which is quite impactful on the theme: reduction of the working hours per week (without reducing salaries).

From what I could find online, and frankly I’m not a specialist in China’s labour legislation (informed comments on the subject are welcomed), China generally follows a 40h work week, however, there are ways to go beyond it in the form of overtime or alternative arrangements.

So let’s assume that China changed it’s legislation to a 30h work week, without reducing salaries, and with minimal loopholes for overtime.

This immediately would force businesses to contract more people, reducing unemployment rates, which are particularly high among China’s youth as pointed above by others.

With higher employment, demand would rise, as some people previously unemployed would now have a job, and those in precarious working conditions (for example, in the so called gig economy, uber and so on) could move to jobs that have more robust worker rights.

Finally, there would be a big political impact aswell, since with a tighter labour market, workers would be in a better position to bargain for pay rises and better working conditions.