Yves here. This post documents the role that rising levels of immigration played in labor organizing in the US. As you’ll see below, at a local level, it increased the formation of skilled (“craft”) unions but did not appear to result in a rise in unions for unskilled workers. One would have to think this result was not due to a want of effort, but to the workers’ relationship with their employer being too casual for them to have enough bargaining leverage.

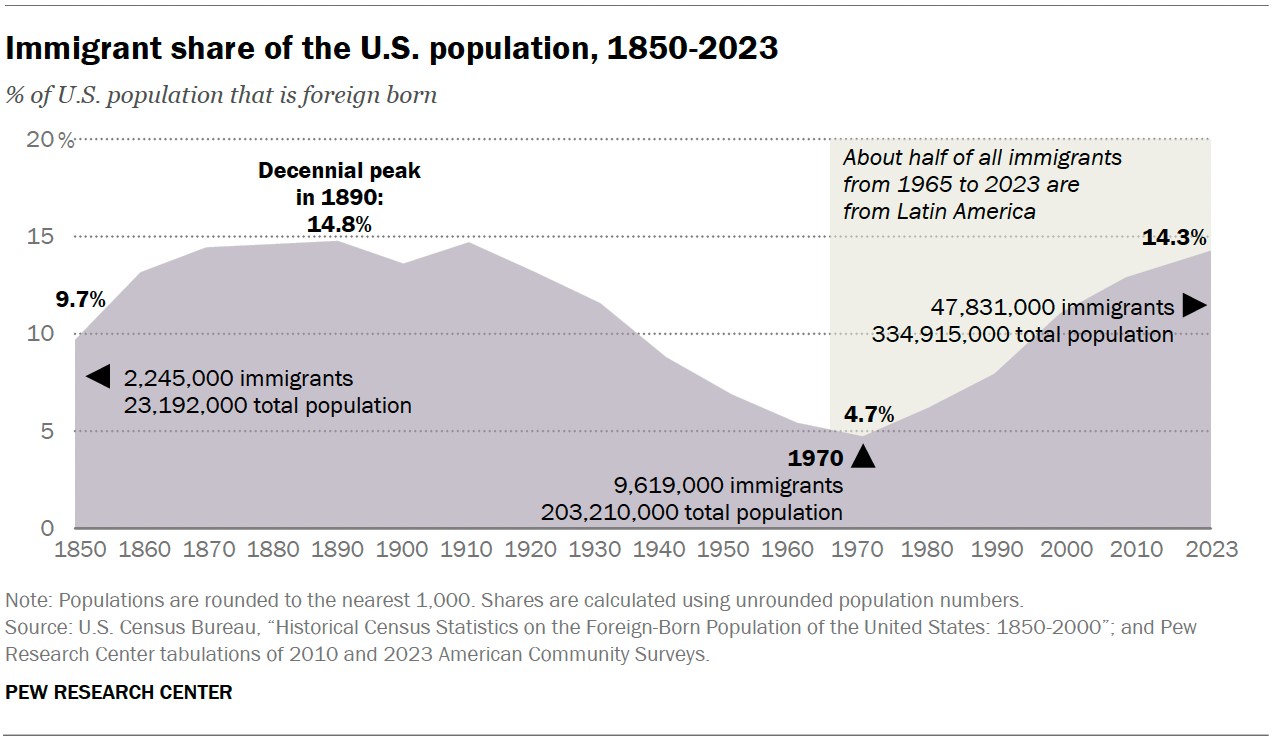

A recent report by Pew Research included some useful historical data:

My dim recollection, and labor history experts are encouraged to correct me, unskilled unions did not get traction until the shift to assembly lines, which resulted in large-scale employment of labor that had not mastered a trade. That was later than the time frame of this study but also did not strongly overlap with an immigrant surge. Then, due to the value that these factories had tied up in plant and inventories, plus the fact that the workers had learned how to operate particular machinery in it, even though that did not rise to the level of skilled labor expertise, did represent a training/time cost for employers, so that a factory-wide strike would make it burdensome and complex for the owners and factory floor managers to bring in enough scabs to get the facility running on a more-or-less normal basis, even assuming enough scabs would cross the picket lines.

One therefore has to wonder if the recent rise in successful unionization efforts is similarly the result, or at least partly the result, of our recent immigrant surge.

By Carlo Medici, Postdoctoral Researcher Brown University; PhD Candidate Northwestern University. Originally published at VoxEU

Despite fluctuations in membership, labour unions remain pivotal in today’s economy. However, evidence regarding the forces behind the unions’ emergence and growth remains limited. This column examines how mass immigration from Europe to the US in the early 20th century shaped the rise of American labour unions. Immigration fostered the emergence of organised labour, especially among skilled workers. Low-skilled workers, however, struggled to sustain unions. Unionisation grew more prominently in counties that received immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe and in counties that displayed stronger anti-immigrant sentiment.

Labour unions have long shaped the economic and political landscape of advanced economies. Throughout the 20th century, they reduced inequality (Farber et al. 2021, Osorio-Buitron and Jaumotte 2015), improved working conditions (Rosenfeld 2019, Bryson et al. 2020), and influenced policies (Ahlquist 2017) and political systems (Acemoglu and Robinson 2013, Ogeda et al. 2024).

Despite fluctuations in membership, unions remain pivotal in today’s economy (OECD 2019). In the US, union approval rates recently reached 70% (Gallup n.d.) – one of the highest levels in 90 years – and the number of workers involved in work stoppages surged by 141% in 2023 (from 224,000 to 539,000) (Ritchie et al. 2023). In other parts of the world, such as Europe, where collective bargaining has a strong tradition, organised labour continues to expand into previously unorganised sectors and influence labour market conditions.

Yet, despite their enduring importance, the empirical evidence on the forces behind unions’ emergence and growth remains limited. In a recent paper (Medici 2024), I examine how mass immigration from Europe to the US during the early 20th century shaped the rise of American labour unions.

How immigration impacts unions is ambiguous. On one hand, increased job competition can motivate workers to unionise to defend wages and employment. On the other hand, a larger labour supply may make it easier for employers to replace uncooperative or striking workers, weakening unions’ bargaining power. Whether immigration fosters or hinders unionisation is ultimately an empirical question.

The early 20th-century US offers a compelling setting to examine this question. The US was already the world’s largest economy (Bolt and Van Zanden 2020), and the labour movement began expanding nationally (Foner 1947). Many unions founded during this period remain influential today. This growth occurred despite significant challenges to organising, as employers could legally dismiss or replace unionising and striking workers without facing penalties (Taft 1964). Immigration played a central role in shaping these dynamics. Between 1850 and 1920, around 30 million European immigrants entered the US, transforming local labour markets and creating both opportunities and challenges for organised labour (Figure 1).

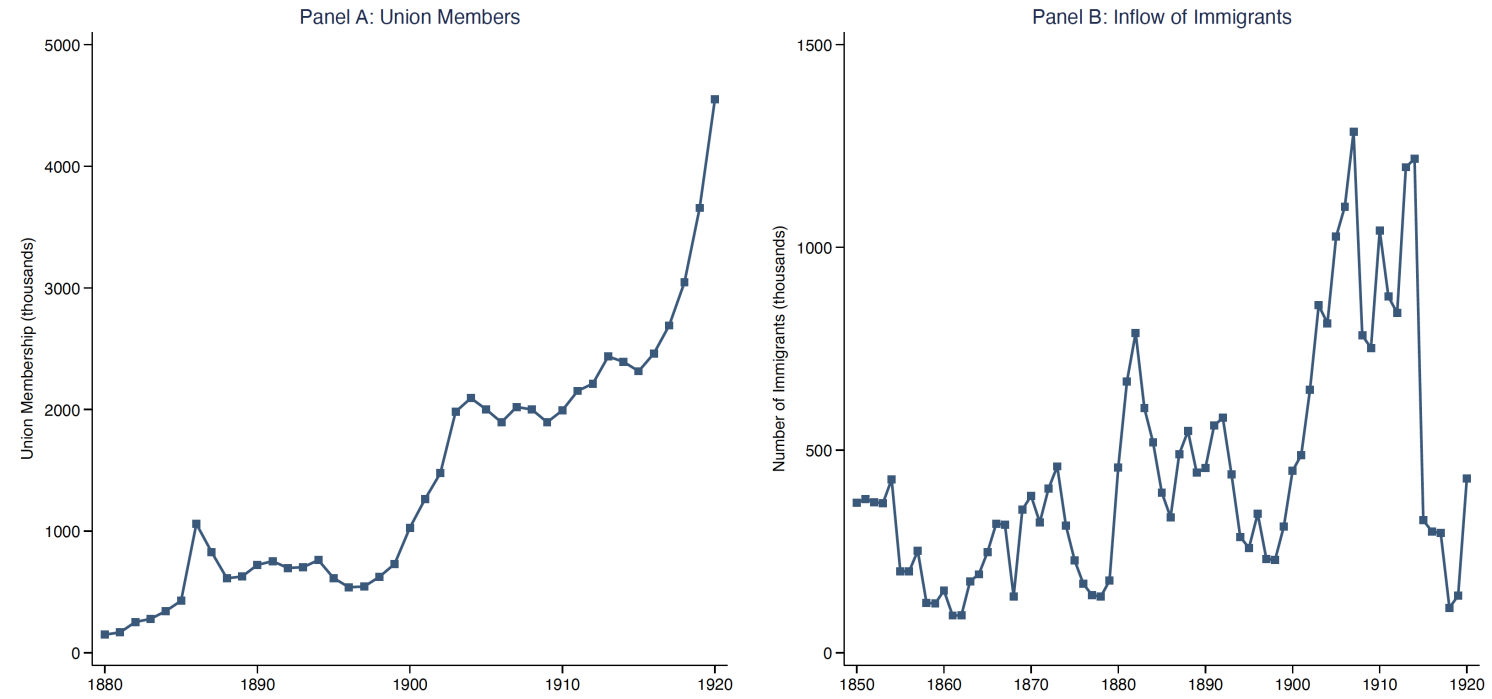

Figure 1 Number of union members and inflow of immigrants to the US, 1880s to 1920

Notes: Panel A shows the total number of union members in the US between 1880 and 1920 (Freeman 1998). Panel B shows the inflow of immigrants to the US between 1850 and 1920 (Immigration Policy Institute).

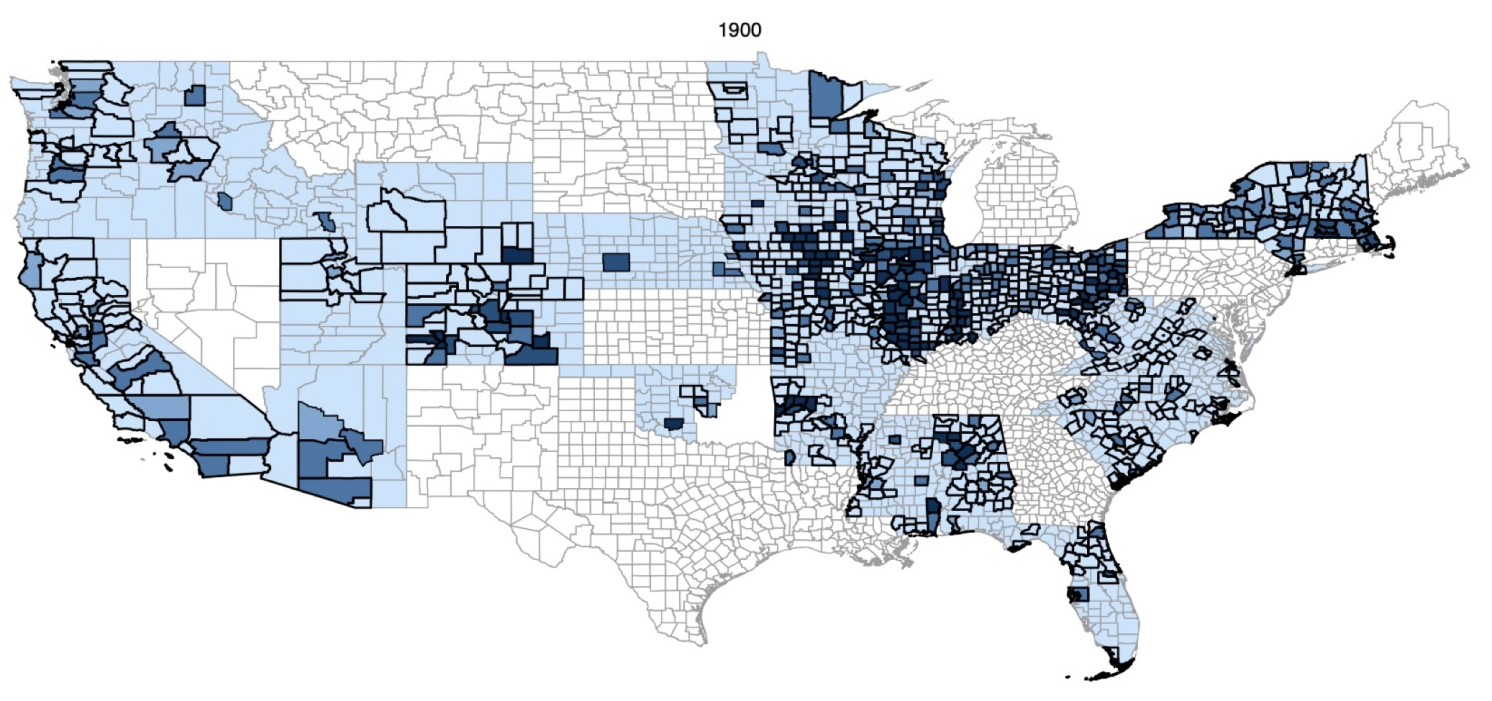

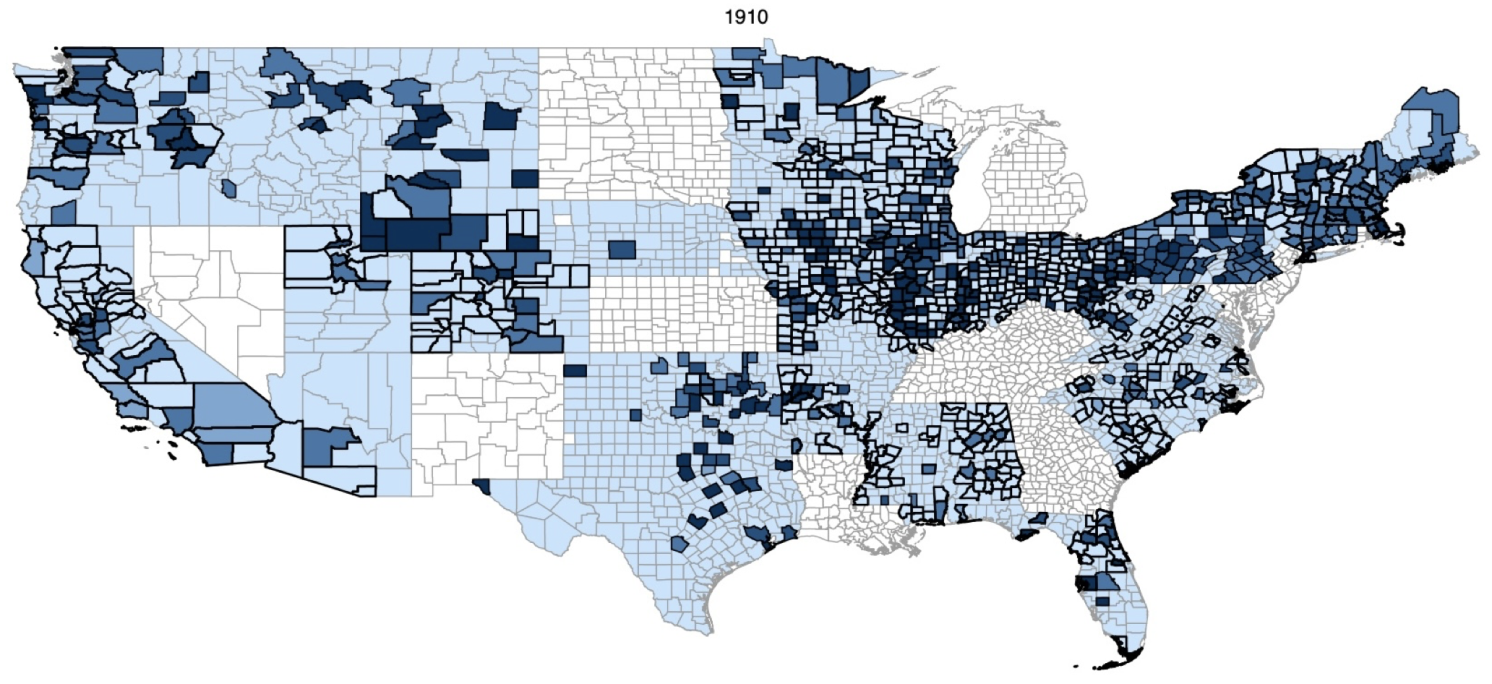

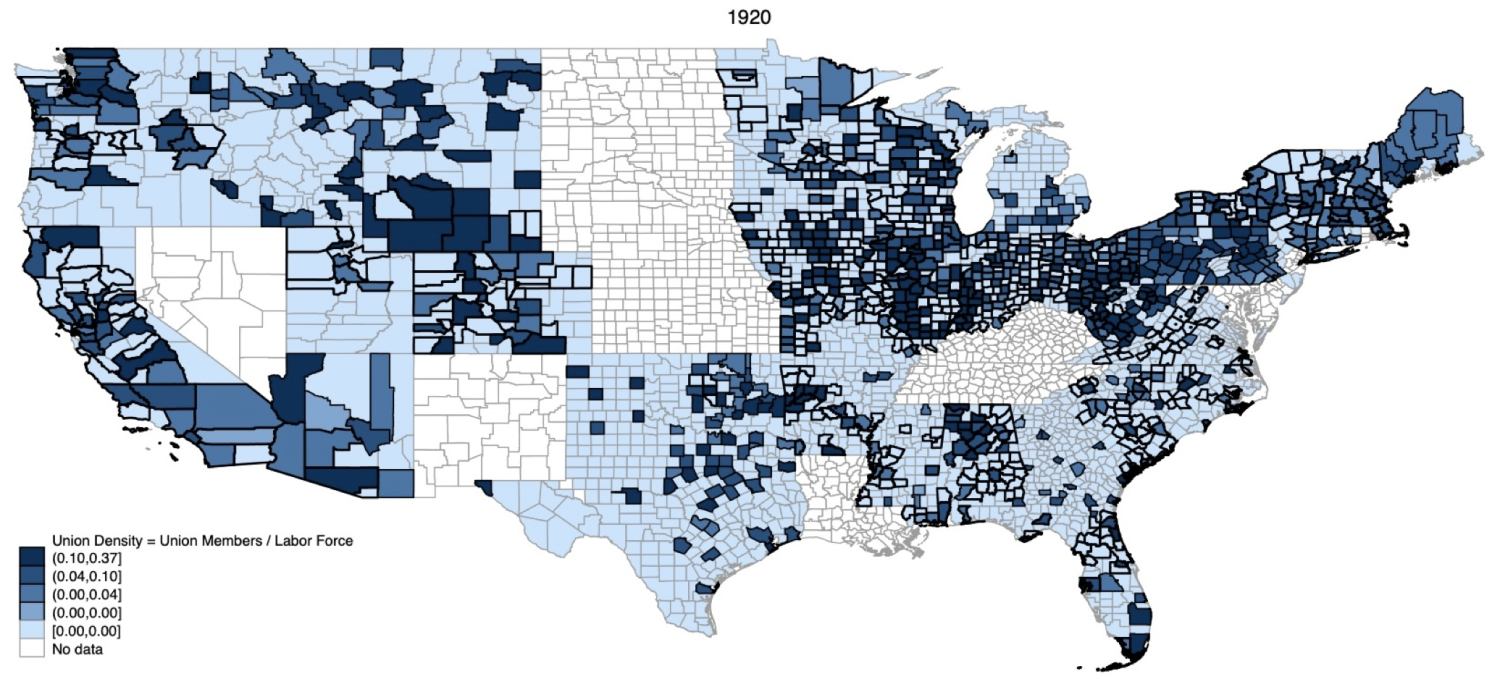

Studying the relationship between immigration and unions presents two key challenges: measuring local unionisation and establishing causal effects. To measure unionisation, I digitised archival documents on unions affiliated with the American Federation of Labour between 1900 and 1920 – a period when American Federation of Labour unions represented over 80% of union members nationwide. These records, drawn from the convention proceedings of state federations of labour, provide detailed information on the number and location of union branches across the country, and allow me to construct novel estimates of union membership. These data provide the first comprehensive, local-level measurements of historical union presence and density in the US (Figure 2).

To estimate the causal impact of immigration, I employed a shift-share instrumental variable approach (Card 2001). This method leverages chain migration patterns, whereby immigrants tend to settle in areas with established communities from their countries of origin.

Figure 2 County-level union density

Notes: These maps display county-level union density (i.e. the number of union members as a fraction of the labour force) in 1900, 1910, and 1920. The legend represents the deciles of the distribution in 1920.

Source: Author’s calculations from convention proceedings of the state federations of labour (American Federation of Labour unions).

Main Results

The results show that immigration fostered the emergence of organised labour. Counties that received more immigrants as a share of the population experienced increases in union presence, the number of union branches, the share of unionised workers, and the number of union members per branch.

Immigration spurred unionisation both at the intensive and extensive margins – expanding unions in counties with an existing labour movement and establishing new unions elsewhere. For every 100 immigrants entering the average county, union membership increased by nearly 20 workers. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that without immigration, average union density (i.e. the share of unionised workers) would have been approximately 22% lower between 1900 and 1920.

Mechanisms

Why did immigration promote unionisation? The evidence is consistent with existing workers unionising in response to immigration for economic as well as social motivations.

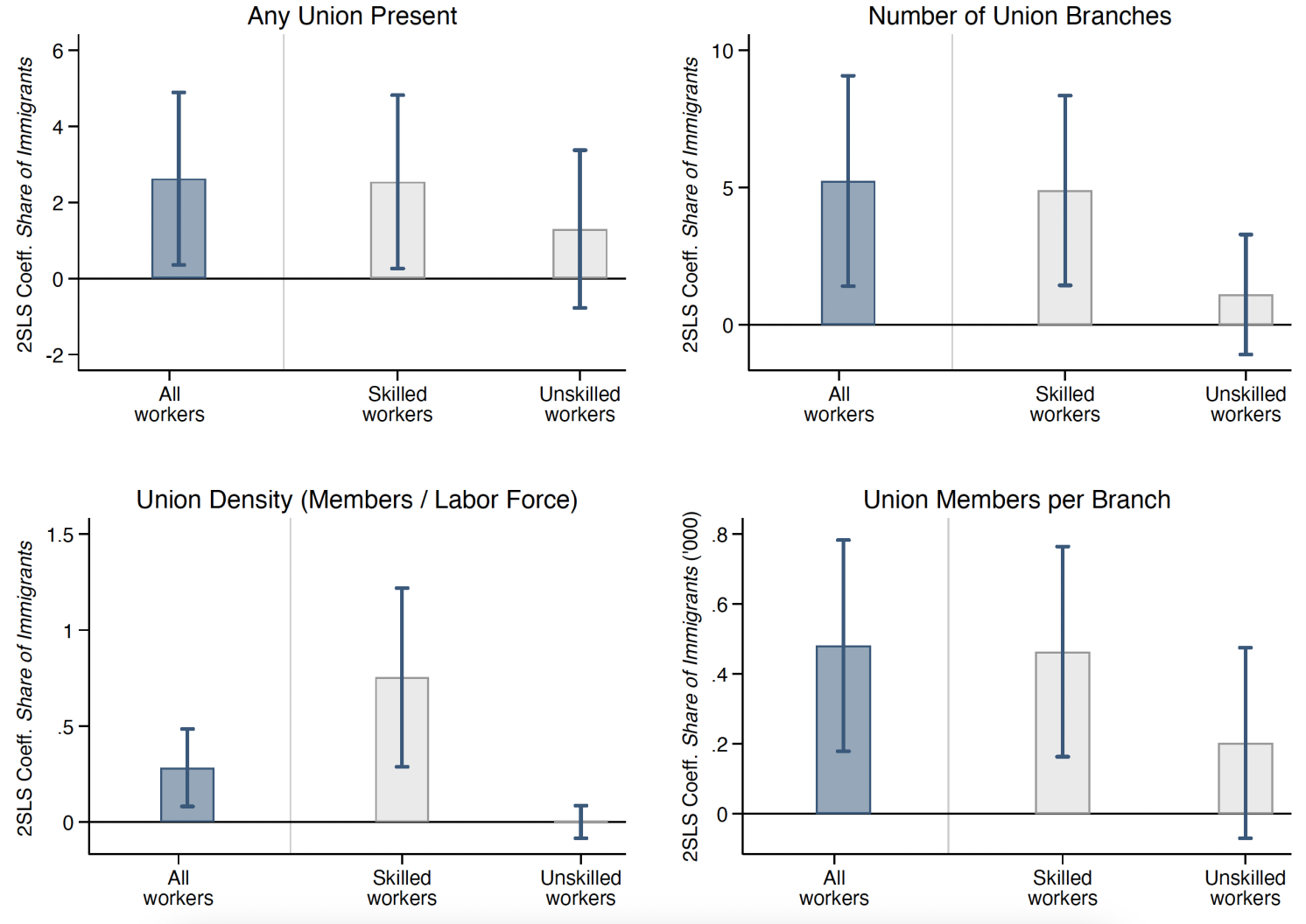

Immigration affected unions in skilled and unskilled occupations differently: it spurred unionisation among skilled workers but had smaller and statistically insignificant effects for unskilled ones (Figure 3). Skilled workers, such as those in craft occupations, organised to protect their jobs and wages. Their specialised skills acted as barriers to entry, making them not immediately replaceable and enabling them to form or join unions. This allowed them to exclude new workers from their occupations and prevent outsiders from acquiring the skills required for these jobs. In contrast, low-skilled workers, such as labourers, struggled to sustain unions. Their jobs could be easily and immediately filled by newcomers, which reduced their bargaining power and made unionisation efforts in response to immigration largely unsuccessful.

Figure 3 Immigration and unionisation among skilled vs unskilled workers

Notes: This figure shows the coefficients and confidence intervals from two-stage least squares regressions examining the effects of immigration on unionisation. The blue bar on the left displays the effect on all workers, while the grey bars on the right show the effects on skilled and unskilled workers separately.

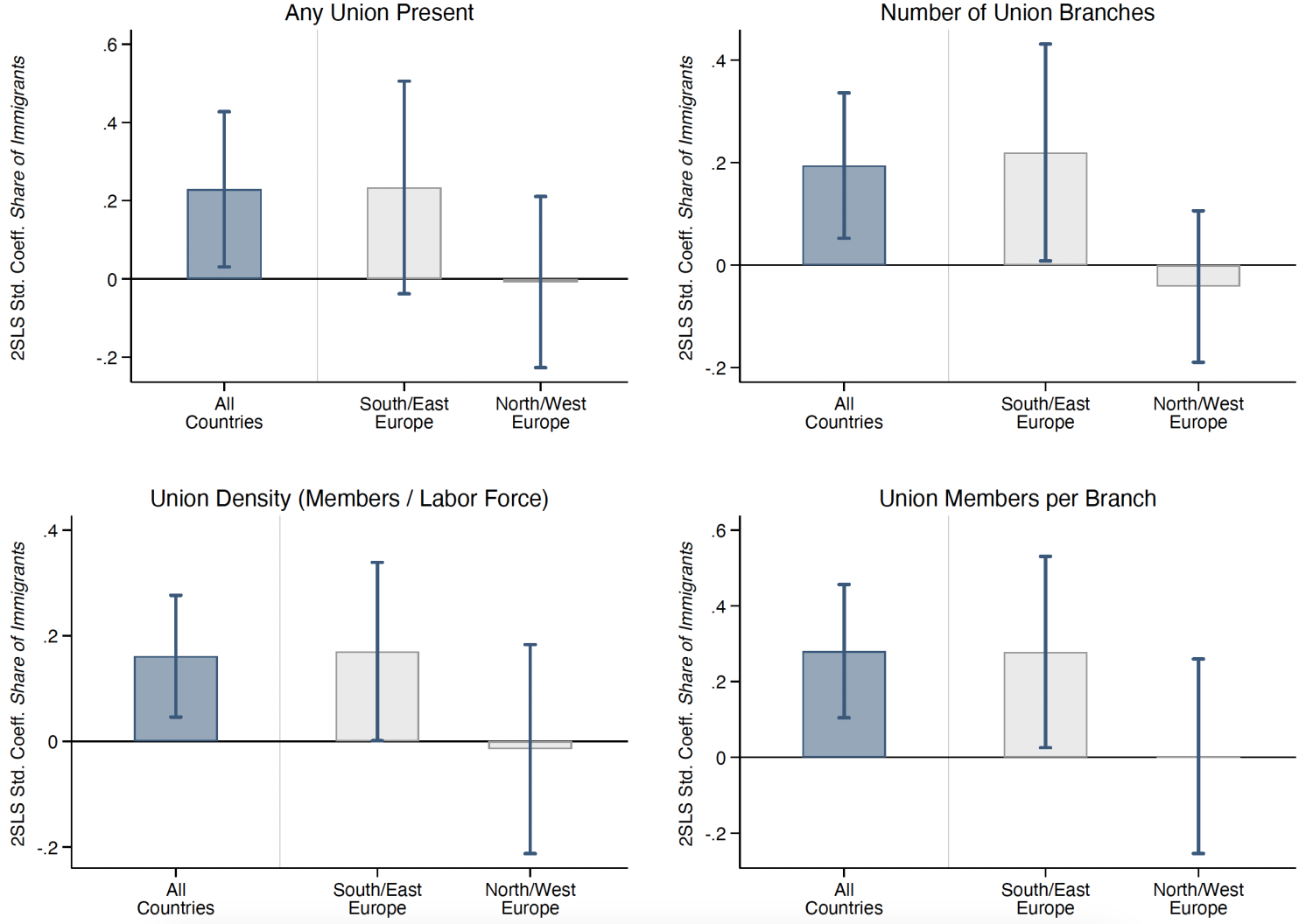

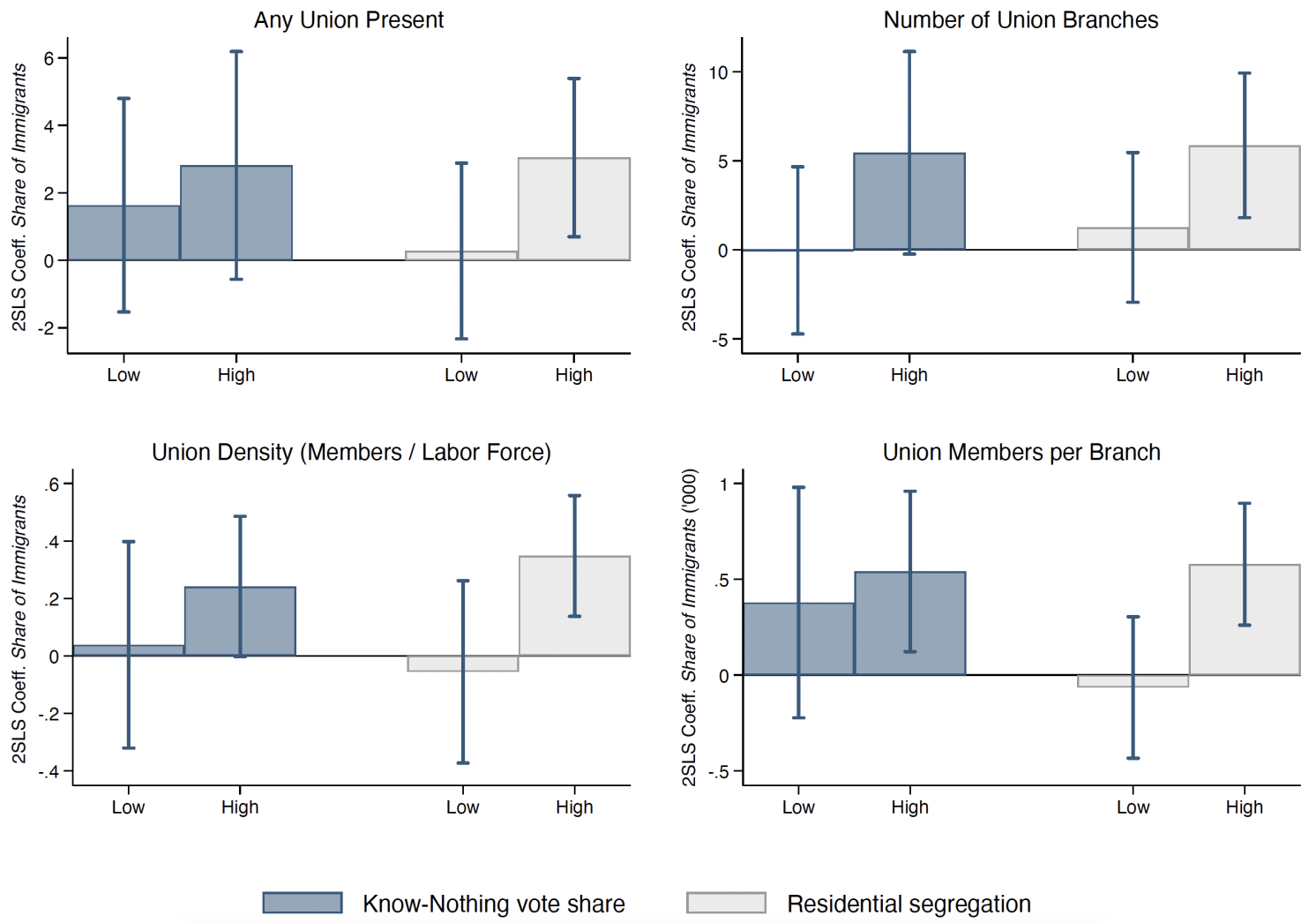

Alongside economic motivations, the results also support the role of social factors in the expansion of labour unions. American Federation of Labour unions often adopted nativist rhetoric, portraying immigrants – particularly those from Southern and Eastern Europe – as culturally distant and less likely to assimilate or unionise effectively. These attitudes were reflected in unionisation patterns. Unionisation grew more prominently in counties that received immigrants from culturally distant regions (Figure 4). It also expanded more in areas that likely displayed stronger anti-immigrant sentiment, such as those with strong historical support for nativist movements like the Know Nothing party or higher levels of residential segregation between immigrants and US-born residents (Figure 5).

Figure 4 Source regions of European immigrants and unionisation

Notes: This figure shows the coefficients and confidence intervals from two-stage least squares regressions examining the effects of immigration on unionisation. The blue bar on the left displays the effect of immigrants from any European country, while the grey bars on the right show the effects of immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe or Northern and Western Europe separately.

Figure 5 Local anti-immigrant sentiment and unionisation

Notes: This figure shows the coefficients and confidence intervals from two-stage least squares regressions examining the effects of immigration on unionisation. The blue bars on the left display the effects for counties with low and high historical vote shares of the Know Nothing party. The grey bars on the right show the effects for counties with low and high baseline levels of residential segregation between US-born individuals and European immigrants.

It is important to note that these results are also consistent with economic explanations. Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe likely had lower wage expectations than those from Northern and Western Europe, making them more likely to be perceived as a threat to existing workers’ conditions. Moreover, fears of economic competition from immigrants may have amplified negative stereotypes and reinforced pre-existing resentment. Overall, the results support the role of both economic and social factors in driving the observed growth of organised labour.

Alternative explanations, such as immigrants disproportionately joining unions or bringing radical ideologies from their home countries, are not supported by the data. The results are also not driven by other major events during this period, such as the political and economic transformations caused by World War I and the First Red Scare, or by differential economic growth experienced by counties receiving larger shares of immigrants.

Long-Term Implications

The effects of early 20th-century immigration on unionisation extend well beyond the historical period studied. Places that received more immigrants between 1890 and 1920 continue to exhibit higher union density today, suggesting that early unionisation created durable institutional advantages for organised labour.

Immigration also reshaped occupational choices. US-born workers increasingly took unionised jobs, likely using organised labour as protection against immigrant competition.

Conclusion

This research identifies immigration as a key driver of unionisation during the formative years of the American labour movement. By examining how immigration shaped organised labour, the study highlights the economic and social forces that influence labour market institutions.

These findings also broaden our understanding of the consequences of immigration, showing that responses to large immigrant inflows are not limited to increased support for conservative parties or anti-immigration policies. Instead, immigration can foster the growth of organisations, such as unions, with broad economic and political impacts.

While the historical context is unique, the results point to broader mechanisms that remain relevant today. Renewed interest in unions may reflect workers’ responses to modern labour market pressures – such as immigration, globalisation, and technological change. These dynamics are not confined to the US. They also resonate with advanced economies facing similar challenges and with industrialising nations undergoing economic transformations comparable to early 20th-century America.

Further research is needed to examine how organised labour responds to economic shocks in different contexts. The dataset assembled for this study provides new opportunities to investigate many additional questions, such as the long-term impact of early unionisation on immigrant integration and its broader impact on the US economy and political landscape.

See original post for references

I’m a little sceptical that immigrants are behind a push to unionize. I can’t find the link right now, but I recall reading an article on old hiring instructions for 19th century steel mills in the US that carefully listed out all the nationalities that could be hired, and the appropriate job for each. At the end were listed ‘Irish’ and ‘Jews’, who were considered unsuitable for any job because of their tendency to labor organising. It should also be pointed out that many early Unions were extremely hostile to immigration. The old mining museum in Butte, Montana has a lot of old union posters on display, many of which were openly racist in singling out Asians (at that time, mostly Chinese and Japanese) and identifying them as scabs, even if they were just local shop owners.

There does seem to be a particular cultural issue with unionisation – David Hacker Fischers book Albion’s Seed noted that some early incomers to the US, such as Scots Irish borderers, seem to be prone to an individualism that made them reluctant to organise. Other groups are perhaps less so.

I’m inclined to think that the connection is less causal – the connection between unionisation and immigration is more likely connected to the type of industry thriving at any particular time. Industrial, construction and infrastructural jobs are simply easier to unionise for a whole range of reasons. When those sectors thrive, unions tend to grow.

I think you misunderstand the piece. Even the “closing ranks” headline highlights the idea that the unions WERE hostile to immigrants.

I believe if you look at where the Scots Irish wound up, they were often became farmers and thus not in the trades.

Alex Carey’s great book Taking the Risk Out of Democracy extensively covers how the National Association of Manufacturers, particularly in 1900 to 1915, engaged in very active pro-immigrant campaigns to blunt union organizing.

Admittedly the author stops at 1920. But his concluding statement suggests that he’s inclined to think that, to put it simply, unionization as a conserving reaction to immigration will continue to be a predominant mechanism in succeeding periods.

If we free ourselves from the quantitative straitjacket his impressive research has set up, other factors loom large in an obvious way. During the 20s and 30s a crisis of capitalism developed that was steadily criticized, in theory and practice, by a growing union movement that was increasingly beyond the control of harmony preachers like the AFL’s Gompers. Roosevelt’s New Deal led to a significantly greater state tolerance of unions as “enlightened” state managers sought to accommodate worker demands and prevent, to quote a poster from the period, factory bathrooms from breeding Bolsheviks. And so on.

I’m sketching a phase-oriented analysis here that loads on post-1920 history. But we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that key “variables” in that history emerge out of the destruction wrought against non-nativist labor efforts prior to that. The crushing of the Knights of Labor and the IWW worked to make the author’s analytic responsibilities for the period in question more manageable.

There was the era of union struggles and then the era of union success when auto workers could have a middle class lifestyle and the class struggle aspect faded into the background. I’ve been a member of a union and all my fellow members were Republicans.

I suspect big capital’s current strategy is to answer unionization with AI scabs and technology rather than Pinkertons and billy clubs. This will hardly of course be a formula for social harmony so the security guard business will soar. Maybe they can get unions.