The just-started fight over how and how much to pay for houses destroyed or damaged in the extensive and still-burning Los Angeles foreshadows yet another ratchet down in living standards for Americans. The notion that it is economically and politically unworkable to insure against climate change is just starting to take hold in the business community. But the immediate focus still seems to be on how to tinker with insurance, as in how to preserve the private insurance industry, as well the related issue of how not to have government budgets at various levels consumed by the costs of socializing these risks. And so the current battles are over who will bear costs, as opposed to trying to deal with systemic issues, such as how housing in many markets was already unaffordable to many due to neoliberal, rentier-friendly policies.

Forgive me for using a new article by Greg Ip at the Wall Street Journal as a barometer of what I call “leading edge conventional wisdom,” here among the finance executives and finance-connected policymakers. Ip for many years was the Fed reporter for the Wall Street Journal and was influential, seen as preferred outlet for the central bank’s thinking. After a stint at the Economist as its US economics editor, he returned to the Journal as its chief economics commentator. I think of him as banking’s answer to the Washington Post’s spook whisperer David Ignatius.

There’s an underlying incoherence to the Ip article, The World Is Getting Riskier. Americans Don’t Want to Pay for It. While he does a good job of setting forth many of the parameters of the problem, of climate change plus high real estate costs translating into loss exposures that are buckling and look likely to break the current insurance, model, he averts his eyes from what is sure to follow next. On the real estate front, high cost and/or thin coverage insurance will translate into much more stringent, as in generally much reduced levels of lending against property. That means lower real estate prices, which is a loss of wealth. This isn’t just at the individual level; think of all of the public pension funds and insurers (!!!) invested in real estate funds and public REITS. Even more telling, dean of quantitative investment analysis Richard Ennis concluded that the reason stock and real estate prices have become more correlated is that public companies have substantial real estate exposure, with the market value of owned real estate representing as much as 40% of the value of US traded equities.

What is disconcerting is that Ip rolls together other areas in which risks have been more and more socialized to argue that they will in the end need to be restricted somehow, specifically banking and health insurance. In the banking arena, the proximate cause goes back to the blatant Obama-Geithner-Bernanke failure to implement tough regulations in the wake of the global financial crisis. To remind readers, the US was in such a panic when Obama took office, and eager for strong leadership, that he could have made FDR-level reforms but instead chose to preserve the status quo ante as much as possible. An example: the extension of guarantees to money market funds on the same basis as banks, which pay deposit insurance for that privilege, should have been rolled back over time to a modest level, like $25,000, and the funds should have been charged FDIC-like fees for the privilege.

Instead, Ip cites the bailout of uninsured depositors in the Silicon Valley and Signature Bank as proof of the over-socialization of risk. Here I agree, but Ip fails to explain what went on. The uninsured depositors in both institutions consistent substantially of very connected individuals (why they had such big balances at banks as opposed to in Treasuries is beyond me, since these customers were typically sophisticated investors and/or had financial advisers), so this was a politically-driven rescue. The press misleadingly made much of companies that have to hold large balances at banks, if nothing else right before they issue payroll checks, when they could have been bailed out separately. Moreover, it is just about never mentioned that the Fed once offered accounts to banks for precisely this purpose, assuring the safety of funds on deposit for payrolls, but lobbyists got the Fed out of that business.

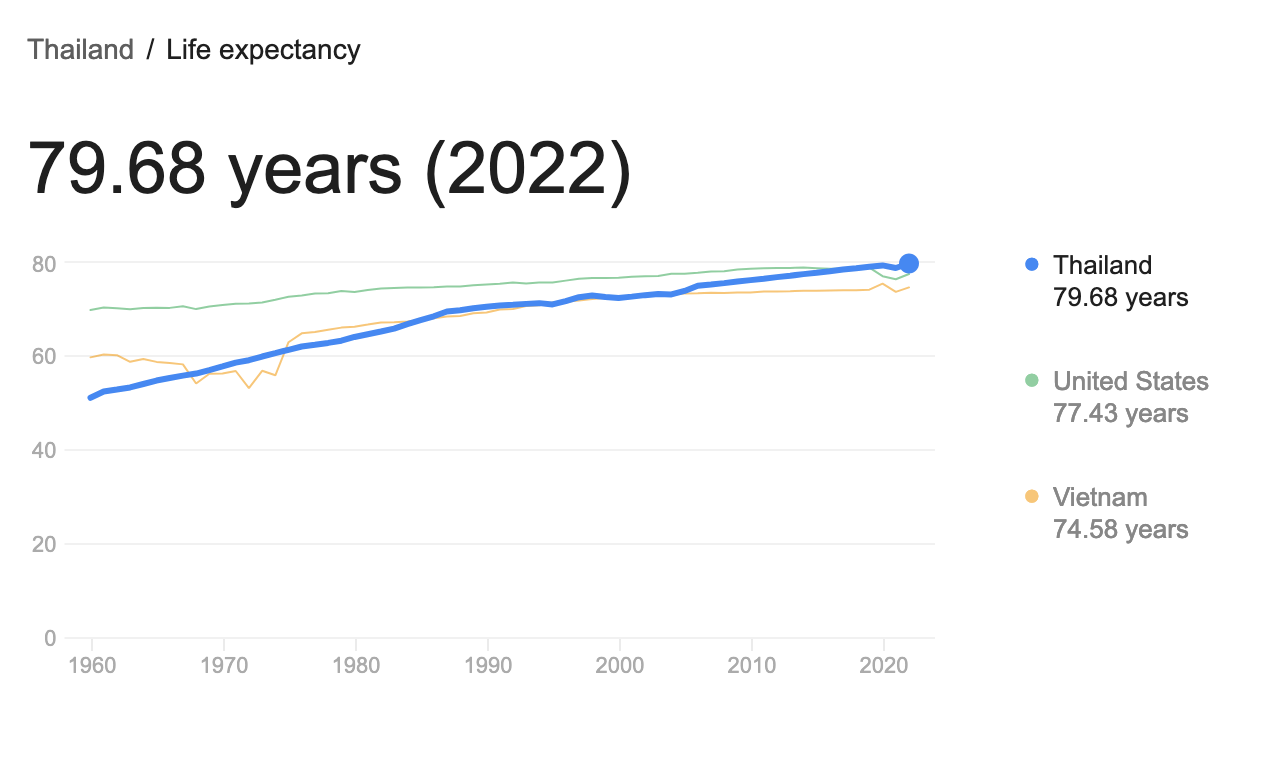

On the health insurance front, Ip is even more misleading. Nowhere does he acknowledge that the US has uniquely expensive healthcare. Here in Thailand, with GDP per capita of only $7,000, a visit to a doctor is 30 baht ($1) in a Thai hospital (nearly all doctors practice out of hospitals). Another indicator: rabies shots are famously expensive in the US. Here they are cheap, and I am told about half the Thais have had them (due to the large number of feral dogs around temples). And health care is considered to be high caliber by global standards due to the monarchy having made it a priority. That is likely a contributor to Thais now having a higher life expectancy than Americans.

So the high cost of insurance here is due to the supersized cost of medical care, which in large measure to neoliberalism and looting, such as allowing drug companies to advertise drugs on TV, which substantially contributes to pharma companies spending more on advertising than they do on R&D.

Yet Ip tries to sell the idea that evil Obamacare is the cause:

In fact, long before that [Luigi Mangione] shooting, the Affordable Care Act had constrained insurers’ ability to base premiums on risk, by prohibiting them from charging more to people with pre-existing conditions or denying coverage altogether.

The ACA also stipulated that insurers spend at least 80% to 85% (depending on the plan) of premiums on benefits. So while denials, deductibles and copays may, at the margin, affect profits, ultimately they serve to control premiums.

Help me. When the ACA was passed, the stock prices of insurers went up. That is because they were allowed LOWER benefit payouts relative to premiums than was prevalent at the time (90% was the norm then). And as most Americans know, Obamacare plans regularly offer thin networks and have such high deductibles so as not to qualify as what most think of as health insurance, but instead high-cost catastrophic coverage plans.

In addition, not only are Obamacare plans attractive for insurers, but they also represent only a comparatively small portion of the insurance market.1

But with this detour to establish where Ip is coming from, let’s turn to the main event, his take on Los Angeles and the looming problem of climate change damaging real estate on a widespread basis. From his story:

The latest example is California. Earlier this month, JPMorgan estimated the fires around Los Angeles had inflicted $50 billion in losses, of which only $20 billion were insured…..

Hundreds of thousands of homeowners shifted to California’s state-run backstop, the Fair Plan, whose exposure has tripled since 2020 to $458 billion. It has only $2.5 billion in reinsurance and $200 million in cash.

Ip does not source his claim about the FAIR plan. Other sources confirm the general picture is dire, but Ip seems to be over-egging the pudding. From the Los Angeles Times over the weekend:

Forking over billions of dollars could wipe out the plan’s $377 million in reserves, as well as $5.78 billion worth of reinsurance the FAIR Plan announced Friday it had. The reinsurance requires the plan to pay the first $900 million in claims and has other limitations.

“Reserves” and “cash” are not the same thing (FAIR can presumably sell assets to monetize more of its reserves” but the Journal under-reporting the reinsurance total is a serious lapse. The LA Times story usefully points out that most of the destroyed Los Angeles homes did not have insurance through FAIR, although its figures are number of homes, and not insured value:

Based on preliminary estimates released Friday, the plan said that it has insured 22% of the structures within the Palisades fire zone as defined by Cal Fire, giving it a potential loss exposure of more than $4 billion. And it has insured 12% of the structures in the Eaton fire zone, giving it a potential exposure there of more than $775 million.

So far, the plan said it has received 3,600 claims but expects that number to grow and has boosted staff to handle the volume. It said it typically receives claims representing 31% of its total exposure, but its actual losses can be different.

But either way, FAIR is set to be hit with more in claims than it can pay out. So what happens then? Again from Ip:

If the Fair Plan runs out of money, it can impose an assessment on private insurers to be partly passed on to all policyholders. In other words, the costs of the disaster will be socialized.

Notice the argument that follows:

A central feature of insurance is risk pooling: The combined contributions of the community cover the losses incurred by members of the community in a given year.

Another feature of private insurance is actuarial rate-making, that is, calibrating premiums to the customer’s risk. That’s to prevent “adverse selection,” in which only the riskiest people buy insurance, and moral hazard—the tendency to encourage risk by undercharging for it.

But some activities or individuals are so risky they could never obtain, or afford, private insurance. That’s when risk gets socialized. The federal government’s expansion since the 1930s has largely been through the provision of insurance: Social Security, unemployment insurance, health insurance for the elderly and poor, deposit, mortgage, and flood insurance and, after Sept. 11, 2001, terrorism insurance.

In other words, the coming climate change crisis, which indeed IS uninsurable, is serving to make an argument against all sorts of government provided guarantees, many of which would be affordable if properly run (start with Social Security, where the easy fix is raising the wage cap on payroll taxes, unemployment insurance, and deposit insurance, which is underpriced, albeit allegedly not severely).

A new article in Dissent by Moira Birss and MacKenzie Marcelin describes how the slow motion collapse of homeowner’s insurance is further along in Florida:

Florida’s political leadership has attempted to address these problems with market deregulation and financial incentives. Several public institutions also help to prop up the private insurance market, including Citizens Property Insurance Corporation, a nonprofit public company created as an insurer of last resort in 2002, and the Florida Insurance Guaranty Association, a state-run fund that pays policyholder claims in the event that an insurer goes bankrupt.

Despite these efforts, Florida is having trouble retaining large, national, diversified insurance companies, which are more financially stable and often more affordable…

Without this ability to spread risk, small insurers are much more dependent on transferring financial risk to other entities, like reinsurers (insurers for insurers), the costs of which they then pass on to consumers. And consumers in Florida are paying the price: homeowners insurance rates in the state are the highest in the nation, averaging over $10,000 per household per year. In some counties, people are paying over 5 percent of their income on policies with Citizens.

Despite these problems, Florida’s politicians have continued to prioritize creating favorable regulatory conditions for private insurers. One way they’ve done this is to impose a “depopulation” mandate on Citizens, meaning it must force some of its current policyholders off its plans and onto private plans, even if those plans are more expensive. Despite this, Citizens is now the largest insurance company in the state….

Policymakers in the state have responded with measures to raise Citizens’ premium rates and further encourage depopulation…

To address this issue, state leaders have permitted Citizens to levy emergency fees on nearly all statewide property insurance policies for as long as is required to repay debt. This means that a serious financial loss for Citizens and other Florida insurers could result in additional fees for residents already dealing with a catastrophe. The Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund (a state-run provider of insurance for insurers) and the Florida Insurance Guaranty Association are backed up by yet more emergency fees on policyholders, meaning they could face multiple stacking fees during a devastating hurricane season.

Unlike most pieces on this coming train wreck, the Dissent authors Birss and Marcelin are so bold as to propose a remedy. It’s impressively comprehensive, and could go a fair distance towards alleviating the severity of the coming train bearing down on large chunks of the built environment. But it does not acknowledge that a lot of communities should be relocated in full sooner rather than later, something societally we are not set up to do.

And as you can see, it suffers from other versions of the classic Maine problem, “You can’t get there from here,” starting with who will pay and how to get buy-in to the massive new government powers that would be necessary. We’ll excerpt a few paragraphs to give readers an idea:

If we want different outcomes, we must reimagine our disaster risk finance system so it reduces risk and provides protection fairly. That’s why we propose a new policy vision for home insurance in the United States: housing resilience agencies (HRAs). Given that insurance markets and much risk reduction and emergency management are regulated and managed at the state level, our policy proposal focuses on state- and territory-level implementation.

State HRAs would have two primary functions: to coordinate and oversee comprehensive disaster risk-reduction activities, and to provide public disaster insurance that offers equitable protection. An HRA in Florida, for example, might implement a roof-strengthening program in the historically Black Miami neighborhood of Liberty City so homes are better protected against hurricanes, and then provide affordable insurance for those same homes.

HRAs would coordinate and oversee comprehensive disaster risk reduction to limit damage before disasters strike. As such, HRAs would play a key role in land use policy by developing, implementing, and enforcing building codes for preventing construction of new housing and other infrastructure in high-risk areas, like easements or setbacks along coastal and other flood-prone areas. Such restrictions are essential to ensure that the rich don’t get to keep building in beautiful but risky areas and then demand disaster relief paid for with public money.

HRAs would also carry out holistic, community-oriented risk reduction and decarbonization for existing housing that would combine structural fortifying measures with energy efficiency updates. And they would institute comprehensive, science-based, equitable, and democratic mechanisms to proactively protect people at the greatest risk of disaster by supporting them in relocating to safer, affordable housing.

Even with all these risk-reduction measures, disaster insurance will still be necessary. And it is public disaster programs that provide the best way to spread the risk of unpreventable disasters and ensure equitable access to post-disaster recovery funds, all without the rent-seeking of private insurers. Coverage would be available for homeowners, renters, mobile-home dwellers, and affordable housing providers. Private insurers would still provide the standard policies that cover things like kitchen fires and burglaries, but the HRA would provide disaster insurance for all—a kind of Medicare-for-All system for home insurance.

Please read the article in full, since it has considerably more informative detail on developments in Florida. Despite the disaster in Los Angeles, Florida is the canary in the coal mine as far as home insurance “adaptations” to climate change are concerned.

But as for the remedies Birss and Marcelin propose, if we lived in a world where solutions like that were possible, we would not be in this mess in the first place.

_____

1 From Census.gov. The “direct-purchased insurance” category is overwhelmingly Obamacare but there are some like me who have oddball non-Obamacare direct-purchased policies:

- In 2023, most people, 92.0 percent or 305.2 million, had health insurance, either for some or all of the year.

- In 2023, private health insurance coverage continued to be more prevalent than public coverage, at 65.4 percent and 36.3 percent, respectively.

- Of the subtypes of health insurance coverage, employment-based insurance was the most common, covering 53.7 percent of the population for some or all of the calendar year, followed by Medicaid (18.9 percent), Medicare (18.9 percent), direct-purchase coverage (10.2 percent), TRICARE (2.6 percent), and VA and CHAMPVA coverage (1.0 percent).

A hurricane hits, say, Florida. The politicians rush down and say we will rebuild. As long as this thinking stays in place it will only get worse. We really don’t need to say any more.

A recent estimate placed the total loss from an east coast of Florida hurricane at something like $1.5 Trillion in total losses, including economic. This is a when, not an it. Even if it is a third of that the financial sector cannot absorb it.

And, as reported in the FT, reinsurance for property and related is declining. Someone has to pay.

Oh, and I guarantee you that the rules will absolutely, 100%, get changed to protect the FIRE sector. Citizens be damned.

…news item… $4B allocated to Ukraine.

Please don’t do this. It amounts to misinforming readers and is therefore negative value added.

The $3.8 billion is a Pentagon holdover from the Biden to the Trump administration from pre-existing allocations. The relevant number for the purpose of this discussion would be total Ukraine spending….except no way, no how would much of that evah have been used for social purposes, as opposed to different military pork.

My property insurance bill is due. If it weren’t for the short term risk I wouldn’t bother. Hard to see the industry surviving the year, at least in its present form. This thought led to wondering if, a la Obama Care, we will soon see a penalty, assessed on our annual income taxes, for being un/under insured.

Here is Bert and I (Robert Bryan and Marshall Dodge) telling the Which way to Millinocket joke, from 1958, from which we got the phrase “You can’t get there from here”.

The current model doesn’t look like it’s going to be around long, just from the events since August.

I like the Birss et al. solution, as it’s better than the existing. But Ip’s definition is insightful:

This is the advantage of a single payer system. Its fairly intuitive how a single risk pool would work with medical insurance. Property insurance is a lot more complicated. I’ve been thinking about this for decades, when I had to devote a whole chapter of my Engineering MS thesis to disaster response funding. I’m not a finance person, so someone with more experience that I have should take up what follows in detail:

Take the nationwide average (or median, whichever is higher) house price and have default federal insurance for all risk up to that level. Any coverage above that is the realm of private insurance or out of pocket. Exclude the highest, repeatable, predictable catastrophic risk areas from coverage- I’m talking floods, fires, and landslides. Earthquakes and severe weather are essentially random events that building codes can largely mitigate. By using the nationwide average (or median) house price as a cap, it would allow full replacement cost in non-housing bubble areas and might put some drag on future housing bubbles. It would also make development of areas that are obviously going to get whacked by events (fires, floods, ground movement) a lot less prevalent, and also provide incentive for wholesale relocations. The Stafford Act already has the framework and precedent for relocating whole towns out of high risk areas.

There’s a good start of a discussion. I’d like to see it fleshed out and/or torn down so that the kernel of a better way can be created and propagated.

Insurance made quite a good sense for ships.

However, preemptive actions, like building differently, different types of housing using different materials, with buildings placed in less exposed locations will start to be taken more and more in consideration.

So no building in floodable areas, etc, etc…

I like your idea, though I’d argue that building codes (or really something built upon building codes) could address fire risk as well, if the government funded some research that would let them say with some certainty “because of these building practices this home’s risk of damage in a wildfire is virtually nil”.

Builders right now who want this kind of certification, who want to be able to say to buyers “the insurance companies know this home won’t burn, so you won’t need to sell a kidney for insurance,” have no options.

Also, so long as this whole thing is founded on the idea of insuring buildings that are built in places and ways which largely mitigate the risk of catastrophic loss, rich people can join the pool too (though maybe they wouldn’t be eligible for handouts to, say, make their homes hurricane-proof).

Of course this assumes there are ways to adequately wildfire-proof buildings which could be retrofitted. I would hope this would be the case, but as I said, research would need to be done.

The problem is we need to start telling people “no”, but the administrators and officials who would have that responsibility are not trusted by the people. So we go round and round.

The area in California that can be that easily burned down by a combination of drought and high winds should be abandoned. Or, people only allowed to build there at their own risk. No private insurance allowed or public insurance provided. Same with flood prone areas. Same with earthquake prone areas. Same with regions that are regularly assaulted by hurricanes. We can’t design out all risk. We can’t afford to pay for the current levels of risk. We need to start relocating now.

I know this will never happen.

>>The area in California that can be that easily burned down by a combination of drought and high winds should be abandoned

How much of California would be left?

Probably not a lot compared to current maps. But that’s the wrong question, isn’t it?

If we value life and stable communities that are safe from these threats, then the only choice is to move the people away from the danger. If we want to allow people to take risks, and make sure they are aware and prepared for the risks, then we shouldn’t be subsidizing those decisions. The current mix of we want you to be safe but you’re allowed to dance on a knife edge makes no sense. Just like if we care about the people and resources and climate change, we shouldn’t be subsidizing activities like pistachio and almond farming. We shouldn’t allow foreign entities to grow and export water intense crops from California either. We want to do everything and not suffer any consequences. But that can’t work as a plan.

So the question is, what do we want to do? And if the decision comes down to business and farming matter more than people, that’s a decision that means local, state, and federal governments should not be involved in bailing out these communities. If we decide people matter more, then we can’t allow them to rebuild in the dangerous locations.

We need to make decisions. I know we won’t. I know things will get worse and people will claim to be overtaken by events and that there will be no choice but to bail out those entities. Doesn’t make it right.

This would require most of the population of the US to move. For example, most of S. California is at earthquake risk. Not sure which state is volunteering to take in millions of Californians (and shift their politics).

After a century of developer-driven property construction that did not respect disaster zones, most American housing is in inappropriate locations (Coasts, wildfires / drought areas, low-lying lands, etc.). I can’t even imagine the costs or writing all that investment off. It is easier to allow nature to take its (human-driven) climate-apocalyptic course.

Surely not most. As anyone who has driven through it can tell you, most of the West is very thinly populated. The problem is more with cities like Los Angeles or Phoenix where the necessary resources including appropriate land are in short supply. In LA that area around Malibu had burned many times so anyone who lived there should have known the risk just as people who live in flood plains know it. Here in SC beach houses used to be cheap wooden shacks on stilts precisely because of their vulnerable location.

Greed and vanity on the part of the real estate developers and home owners have to be considered. But that would inconvenience some powerful people including our new/old president.

Back in the day when I grew up on the Georgia coast, houses were solid, concrete or brick, and low beneath the canopy of live oaks. Hurricane winds passed right over the houses and the trees mostly stayed upright under their broad and very strong canopies. Pines were the danger. The transitional area of dunes between the ocean and higher ground (6-8 feet in elevation was enough) was the shock absorber and necessarily a no-build area. Water was always a potential problem but wind damage, not so much. Now, stick built McBeachMansions are just behind the mean high tide mark, the dunes are expensive “real estate.” The first Category 4-5 hurricane since the storm of 1820 (IIRC) that penetrates the Georgia Bight will scour the sea islands, leaving sand-covered concrete slabs with a few pipes sticking out. And these areas will become no-build zones once again. Until sea level rise makes them uninhabitable.

It’s overpopulated given the water resources available, not underpopulated. Last thing anyone needs is more Californians.

Imo, “Cadillac Desert” is a must-read regarding California and its water situation.

I also recommend the newer “Oligarch Valley”, http://yashalevine.com/books/oligarch-valley; Levine has been writing about this for years.

Think of all the growth opportunities in the rust belt. The entertainment industry relocated to Toledo, and everyone us happy.

As long as potable water is not required for a healthy entertainment industry. Toledo was without it for a week in 2015, and the algae problems caused by fertilizer runoff haven’t been solved since then. Lake Erie also has a big problem with plastics contamination:

https://www.clevescene.com/news/ripples-of-plastic-documentary-an-examination-of-lake-eries-plastic-pollution-problem-comes-to-the-capitol-45882057

Neoliberalism has pretty much ensured no place is really safe.

The whole Japan is in an earthquake zone, and they don’t seem to be that inclined to moving. They decided to build better. Except when politicians interfere, like for the Fukushima wall, or puting the backup engines in the basement…

Considering the severity of the problem (climate collapse), “telling people no” doesn’t get it. Who do you tell no and where do you say yes? Florida (hurricanes), Vermont (ice storms and hurricanes), Chicago (ice storms – extreme heat), South Carolina (drought, hurricanes, ice storms), Mississippi valley (hurricanes, ice storms, extreme heat), Arizona (no water, hurricanes, extreme heat, fires), Oregon (fires, ice storms) …………… get the idea? You can only go north for a short time, and then you are going south.

Sure, I get it. The problem is getting it doesn’t matter. The weather will do what it does. Fires will happen. The question is what to do about it and who do we support through this process? It is stupid for us to support rebuilding in California as it currently stands. Just like it is dumb for us to build up properties around hurricane and storm surge prone areas. In your list above we can adapt to pretty much any ice storm or extreme heat event provided we have water. The rest of those are things we can’t practically design solutions that eliminate risk.

And yes, who do we tell no is the biggest issue followed closely behind who tells whom no. The “kindest” suggestion I can come up with is a constantly resetting deductible. For example, if federal aid to a citizen following a disaster amounted to 100k$ in one year, the deductible to receive any further assistance in another year is at least 100k$. That would have the effect of forcing people to relocate after disasters. It would also be wildly unpopular.

We’re currently stuck with a situation where we can’t continue to do what we’re doing and we don’t want to change. We’re putting a lot of people’s lives and property at risk because of that approach. You can argue there are different priorities we should take. You can argue there are different solutions we could try. But even then, you’re telling people no. It could be as simple as, no you can’t have wood framed housing anymore. Or, no you can’t irrigate your lawns and gardens any more. My suggestion is, no you can’t live there anymore. But sooner or later you’re telling people no. Which is something we’re very bad at in this country.

I have no problem seeing a wealthy person lose their home and have no recourse through insurance if they knew the risks. I have a lot of problems with our current system that pretends the risks don’t exist and allows the construction of those properties. I have a lot of problems with us lying to poor people about their risks. I have a lot of problems with us forcing everyone else to pay increased premiums and higher state and local taxes because the wealthy want to continue living in the places. I have a big problem with us forcing development into floodplains and the like because it is the only profitable solution. I also can’t stand the refusal to accept a simple proposal that would help many – move east. There are lots of places that have cheap housing and no fire risk, tornado risk, earthquake risk, or hurricane risk. Why do we have to double down on California?

No, you could rebuild with concrete, but that is perceived to have unacceptably high climate costs.

People will have to be told “no,” if not through insurance, then through inability to get mortgages.

And what is your solution if you are saying poor people and middle class people in LA have to move to another state? That is a guarantor of a much lower or maybe even no income due to a lack of a personal network in another state.

Or straw bale. Also, one could dig the houses into the hillsides more so the fire burns over them.

You’re absolutely correct about the income issue. It’s also a trap because for some people moving to a lower cost of living state will insure they can’t move to a higher cost of living place in the future.

You are also correct about the family and friend networks people have to leave if they change regions. Even moving from Southern to Northern California would be a problem if you rely on an aunt of grandmother for babysitting.

I don’t think there is a way to optimize this problem so that all of these concerns are equally balanced. Or even addressed. If you bought a house in fire country, and it burns down, and odds are good it will burn down again in the near future, the value of that house should be zero. If we insist people can live in these places then we’re treating their lives as zero worth objects too. I refuse to do that. They’re people. They’re citizens. We shouldn’t let them put themselves at risk like that.

But then we get back to who gets to who to move. The poor and middle class do not trust government. The wealthy trust government only so far as they can manipulate it. The kindest cut I can think of is to bar people from rebuilding using a market and turn a deaf ear to cries for a bailout or variances. That means watching many communities throughout the United States dry up and blow away.

I hate that those are the options but I don’t see many other choices. We’re going to be having this same conversation in another few months with a different wild fire. Or a hurricane. Or a tornado. Or a flood. So either we value the people and tell them they can’t stay, or we let them accept the risk and they get no support.

Happy to discuss better options if you have them.

Some situations are lose-lose. The rich are already leaving in large numbers. There was already a lot of exodus from LA due to crime rates. So you’ll have an eroding tax base in a state which I imagine will still need a pretty high level of government services, even before getting to the elephant of the room of how to reduce fire risk….which will generally mean costly rebuilding unless you go to minimally-wood-using apartment buildings.

This whole problem also has to be viewed in the context of population increase through immigration in the last 20 years. People need jobs and have to live somewhere. This is one reason why the US meddling with its Southern neighbors is bad. Are we going to have a national discussion about that, beyond the frankly idiotic “build a wall” talk? My bet is the answer is no.

Actually, it has to do with population increase over the past 9000 years. We, as a species, can only produce so much wealth. We currently use, as a species, 9487 times wealth, per annum, than we have created. It doesn’t matter how it is distributed…there ain’t enough. And this is including the 191 trillion dollars that we have created out of thin air.

“you could rebuild with concrete, but that is perceived to have unacceptably high climate costs.”

Over what timeline?

A well built structure, with some maintenance, can last for not tens, but hundreds of years, and be passed down to many generations.

Just about all of the state of California, especially the middle and southern areas, where almost everyone lives is earthquake. Due to the heavy rains we get every decade or so in different parts of the state, flooding and landslides are a given, and wildfires are a danger even to some fair sized towns, nevermind the smaller ones and neighborhoods.

We are talking around thirty million Californians living in areas where insurance of some kind is a necessity. Then there is Washington state, which is vulnerable to massive earthquakes, floods, and a volcano all of which is almost guaranteed to inflict damage worse than what San Francisco enjoyed in 1906. Oregon will also get slammed with an earthquake when Washington does and as far as I know, neither state has the same earthquake resistant buildings as California has due to the multiple quakes reminding California of the need.

Are we ready to tell most of the West Coast to move?

What is frustrating is that much, but not all, of the danger could be mitigated with different construction that matches the dangers of a local area, even if nobody moves when they should For example, rammed earth instead of concrete or fire resistance roofs. It would take changing the local building codes and time, however, money and stupidity (and corruption) puts a stop to it as developers want to (re)build their buildings as cheaply as possible.

Rammed earth is great for fire but fails in high wind and moderate seismic conditions. Reinforcing the RE structures compromises their fire resistance.

Yes, I understand that one outcome of this approach is saying we’re going to abandon the west coast in large part. We had a good run.

When we who are left revert to living in tents, it will be easier to move, as needs dictate.

Most of Japan is at earthquake risk but they build for that.

GM pointed out that Eastern Europe does not have fires that spread through and are intensified by housing stock because they use concrete. Ditto here in Thailand, where no Thai would put up a wooden or meaningfully wooden structure, and Thailand is markedly less dry that California. Wood houses are similarly not traditional housing stock in the Mediterranean.

However, concrete is considered a bad material too, climate-change wise.

Yes, traditional Japanese building accounts for earthquakes. Modern Japanese building accounts for earthquakes differently too. But either still does a lot better than most of the residential construction in the US. Concrete is great, but it’s more expensive and the craftspeople who work with it for residences aren’t as plentiful as carpenters who can handle stick building houses. Concrete is also considered a bad material for climate change because of the entire production cycle. Mass timber is something people are suggesting for future multifamily construction but that is obviously still a problem for fire.

There’s lots of related details about Japan that make it a poor comparison to the US though. For example, a lot of the housing stick is treated almost as if it’s disposable, and not an appreciating asset. Not a lot of flippers in Japan. The average useful life of a house in Japan is about 38 years or less. That’s incredibly wasteful and not climate friendly either.

Which just gets back to telling people no in the US. No, your house shouldn’t be an asset. As you and others have covered on NC for years, we are unlikely to ever challenge that assumption because so many people rely on the value of their home for other purposes than a roof over their heads.

It is not all concreate, but the supporting structures. The walls are built differently, depending on the construction. i.e. autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) which is concrete that has been manufactured to contain closed air pockets. AAC is one-fifth the weight of concrete. AAC is available as panels and blocks. AAC wall panels are typically used for cladding, but can also be loadbearing.

As an American who has lived quite a few years outside the country and came back, it is very, very hard to talk about anything now. Americans’ mental templates are just so messed up, and the older and more affluent, the more messed up.

Americans need to see the 94% of countries where no one is living in wooden houses (except maybe the very poorest, barter-economy indigenous people). Where a fire engine is a rare sight. Where the middle class ideal is an apartment or townhouse.

Then look around them and have a good freakout. Very likey 10-20% of all that wood is going to burn down or blow over in the next 60 years. How do you price insurance with that kind of risk?

FIRE sector going up in flames? Will I finally be able to buy a home, until of course it burns to the ground?

Have been reading about the CA situation and apparently State Farm said it cancelled all those policies because state law doesn’t allow the increase in premiums to keep pace with the soaring value of real estate and, as we now see, the risk in choosing to live in certain locations.

And is that a bad argument? As for Florida one could point out that there was a time when Florida real estate was considered fodder for Marx Brothers humor since the place was notorious for its hurricanes and swampy land. Here’s suggesting, as does the above article, that the problem is much bigger than greedy insurers. Kenneth Clark once clucked at our “heroic materialism” but America’s money and status obsessed culture may not fit with a sustainable future. People have been saying this for decades but nobody wants to hear it and I include my fellow flyovers as well as the rich and all too powerful. On this inauguration day it could be time to make America humble again. And that will have to start, of course, with our politics.

“… you can get any style you like. You can even get stucco. Oh, how you can get stucco!” – Groucho

“State Farm said it cancelled all those policies because state law doesn’t allow the increase in premiums to keep pace with the soaring value of real estate and, as we now see, the risk in choosing to live in certain locations.

And is that a bad argument?”

That’s a good point. It might be possible to insure the cost of rebuilding a house.

OTOH, AIG went broke trying to insure financial players capital gains. State Farm may not need that kind of trouble.

Make America Humble Again!

Make America Humble For The First Time!

And America was humble, uhm, when?

The Quakers in the Midwest were humble back in the day. There are still Amish in Pennsyltucky and Mennonites here in Iowa and elsewhere. We might want to get used to providing all of our own food again, but that is a lot of work, that.

Make America Amish Again?

Thanks for this post.

I wonder how much larger the damage estimates are now than they would have been 5 years ago, before Wall St. started buying up residential housing in bulk, distorting local real estate markets, and driving housing prices to the moon. Even in my flyover town housing prices are almost double what they were 5 years ago. It’s not because people are earning twice as much money or because a huge number of new people coming in looking for housing. It’s outside money coming in driving up prices. Insurance companies trying to raise rates to cover the increased housing values are stymied in CA by state law. And here we are.

Are insurance companies being blamed for what I think is a Wall St. led housing price bubble driving up costs of housing and insurance? Was this an unintended consequence? /idk.

But the cost of rebuilding a house is what the insurance company covers, not the possibly inflated price of the house prior to the fire.

House price = market value of location + lot value + structure.

Only structure is destroyed.

If a house would cost 200K to rebuild 5 years ago and it costs 250k to rebuild now, from the insurance company’s standpoint, that is a +50K exposure increase for the insurance company.

The insurance company would not care about the market value of the house before it burned.

I was always kind of watching Private Equity sucking up houses at the top of the bubble. Maybe we should just let them go nuts in the short them so they can enjoy the ride down.

Peak Housing

Great intro, I haven’t even had a chance to get into the article, but YS’s breakdown is enough for me to chew on this morning.

Lots of other things to think about.

The potential for a 9.0 cascadia earth quake in the total NW from northern california all the way through seattle is possible. That won’t just damage homes, but devastate all the infrastructure.

It wasn’t all that long ago that MT St helens erupted and only because the wind direction was away from Portland did it survive.

Tornados are the most destructive force out there, and only a concrete home would survive that.

Fire? Fire science for homes is 50 years old, they know how to build standard wood homes to the correct standards to stop most damage, there are many examples in the So Cal fires. Concrete siding, no eves, cleaning gutters or no gutters, metal roofs, tempered glass windows, no plants next to the house, for example. And retro fitting most at risk homes wouldn’t be all that hard.

Sure can do full concrete or any number of other types of non combustable construction.

No lack of answers.

But plenty of lack of political will. As usual.

The subtext that I’m getting from the Ip excerpts (I’ll possibly read his piece later; the Dissent piece is more appealing) is that the WSJ continues to push the “privatization” meme — that individuals “can’t afford” to own their own homes, to have adequate healthcare, or a secure old age. The unspoken part is that these “uninsurable”properties must be foreclosed upon and their owners forced into homelessness until they die from exposure and neglect.

It’s the same old tired Private Equity buyout model in which the individual doesn’t “own” their necessary assets, but simply is indentured as a revenue-stream to a rentier elite.

Rule No. 1: Because markets.

Rule No. 2: Go die. (hat-tip Lambert)

Maybe before embarking on a “holistic”, “community based”, “equitable” and “democratic” program (speaking solely for myself that vocabulary does not inspire much confidence) we should try allowing existing market based corrective mechanisms to function. Commercial insurers have considerable expertise in the pricing of risk. The growing unfunded exposure of the FAIR plan and Citizens is mostly attributable to political suppression of private insurer rate increases which if allowed might have mitigated the immediate crisis by discouraging new construction, reducing value at risk, shifting self insured risks to deeper pockets and maybe even encouraging improvements in resilience along the lines recommended by the Dissent article.

Exactly.

In California the insurance commissioner has created tremendous market distortions by making appropriate premium increases illegal. That’s why insurers have left the California market.

Even now, the “solution” being sought by California legislators is to permit the FAIR plan to issue bonds, which will do nothing but encourage even more distortions by kicking the can down the road.

California would not be in this position of facing an insurance crisis had it not for years arbitrarily capped the rates charged by private insurers regardless of actual risks.

The people in PP Pac Palisades are in another planet. I sympathize with loss of life but why does anyone worry about million dollar crap shacks? I would guess that half the population is in the top .5 percent. There is a high density of lawyers and agents. I have to pay a few and average is 900 per hour. They funded and backed the mayor. Mike Davis wrote a great book about it 30 years ago. Mexico does not have this problem because they let the hills burn and they burn frequently. The PP problem is that the rich want to live in a high risk area and they want the Muppets to pay for it. The government should block redevelopment and instead make Malibu and PP a public park. By suspending building and safety and coastal commission rules that would block most development they are serving their true blue donors. The vast majority of Angel is have never seen the ocean or Malibu beach. Let the real estate capital lists move to the flats where the Muppets are.

It’s not just Pacific Palisades. Altadena is a historically black neighborhood and significantly middle class.

Thank you for posting this. It is welcome discussion, finally we are getting serious. Many of these ideas have been around for a few decades now – proper land use planning and building codes, etc. The new thing that is unfolding is the complexity of resilience. One aspect that nobody emphasizes is deconstruction-recycling. I’d guess that whole neighborhoods need to be reclaimed in California. The idea being that all those existing houses require lots of updates and they might still burn to the ground. And Salvage isn’t a very exciting industry. But salvaging something really is the very spirit of insurance. And insurance itself is survival and blablablah.

We are in a slow, long process through which humanity accepts that it will have to give up significant geographical areas such as Florida, river flood planes, areas that should really be scrub and desert (Phoenix, LA) etc. as being uneconomic to inhabit. During that process there will be an ongoing “pass the parcel” of costs process that will be tilted against the little guy but still cause significant financial crises.

As was predicted at least a decade ago by some, the property insurance industry will be bankrupted by intensifying natural disasters probably sometime in the 2030s, it simply does not have the reserves to cover the increasing trend into the future. Instead of intelligent central government planning we will get ongoing removals of coverage over vast areas and periodic financial crises as the latest set of disasters drain the insurance company reserves; each time moving to a new, lower, normal.

Yellowstone National Park is a supervolcano, which will wreck much of North America if it erupts. Luckily, that is quite unlikely any time soon. The New Madrid Fault last shook in 1811-12. As I recall, that one rang church bells in Boston and made part of the Mississippi River run backwards. The link mentions damage in Washington DC. My point is that no where in America is really safe from natural catastrophe. So we do need some type of national response to disasters. However, as is discussed above, we need a keen awareness of the need for intelligent risk management, and the courage to follow through with effective policies. A bunch of rich sociopaths with a plan to evacuate to Mars may inspire a good Meryl Streep movie, but is not good policy even for the rich, let alone for the poor.

One other possibility, Jem Bendell was right in Breaking Together, and sometime before 2016 was the beginning of the end for Western Civilization. My candidate for a symbol of that is Trump’s 2015 descent down his golden escalator. The current status report for the collapse is Trump getting a second inauguration on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. We have come a long way down the escalator! (But still a long way to go.)

I’m reminded of the story of Bank of America. After the 1906 SF earthquake, the founder set up a makeshift bank on a North Beach wharf and made loans to local residents with a handshake.

Yeah, that’s not happening these days. Especially the bank swallowed up by Charlotte.