Yves here. This post recaps in detail the many climate/weather disasters of 2024, including a very high level of unprecedented heat across broad swathes of the world. Oh, and the peak year for big-ticket disasters was 2023.

By Jeff Masters. Originally published at Yale Climate Connections

he planet was besieged by 58 billion-dollar weather disasters in 2024, ranking second-highest behind only 2023, which had 73, said insurance broker Gallagher Re in its annual report issued 17. The total damage wrought by weather disasters in 2024 was $402 billion, 20% higher than the 10-year inflation-adjusted average. (Gallagher Re’s historical database extends back to 1990.) A separate report issued January 18 by insurance broker Aon put the total damage wrought by weather disasters in 2024 at $348 billion, with 53 billion-dollar weather disasters.

Increasing Numbers of Billion-Dollar Disasters Primarily Driven by Increases in Wealth and Population

Gallagher Re said that 2024 had the highest-ever number of insured billion-dollar weather disasters: 21, beating the record of 17 set in 2023 and 2020; over 40% of the insured damage was from severe thunderstorms. There has been a steep rise in the number of billion-dollar weather disasters in recent years, and most of this has been driven by increases in severe thunderstorm losses in the United States.

About 80-90% of the increase in damage resulted from factors other than climate change. This point was echoed by insurance broker Aon in a 2023 report, which found that over 80% of severe thunderstorm loss growth could be explained by factors unrelated to climate change. (Hail damage, in particular, is getting a boost from rapid growth in Texas and other Sun Belt states.) However, Gallagher Re warned that climate change amplification of weather events was leading to “weather whiplash,” with rapid shifts from one peril to another.

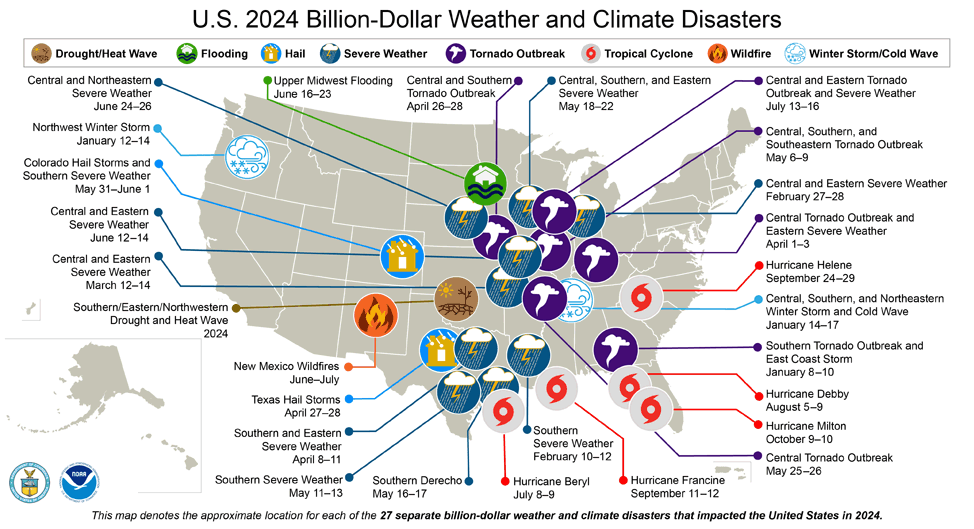

U.S. Sees Its Second-Highest Number of Billion-Dollar Weather Disasters: 27

As discussed in our January 10 post, the inflation-adjusted tally of U.S. billion-dollar weather disasters in 2024 was 27, falling just short of the record of 28 set in 2023. The total cost of 2024’s billion-dollar weather disasters, $182.7 billion, was the fourth-highest on record in the NOAA database. The billion-dollar disasters of 2024 included 17 severe storm events, five hurricanes, one wildfire, one drought, one flood, and two winter storms. The average number of billion-dollar disasters for a full year for the most recent five years (2020–2024) is 23. Using different accounting methods, Gallagher Re tallied 33 U.S. billion-dollar weather disasters for 2024.

Cat clinging to a car for its life gets saved by rescue workers during Hurricane Helene flooding. pic.twitter.com/1oH8P4V7d5

— Oli London (@OliLondonTV) October 13, 2024

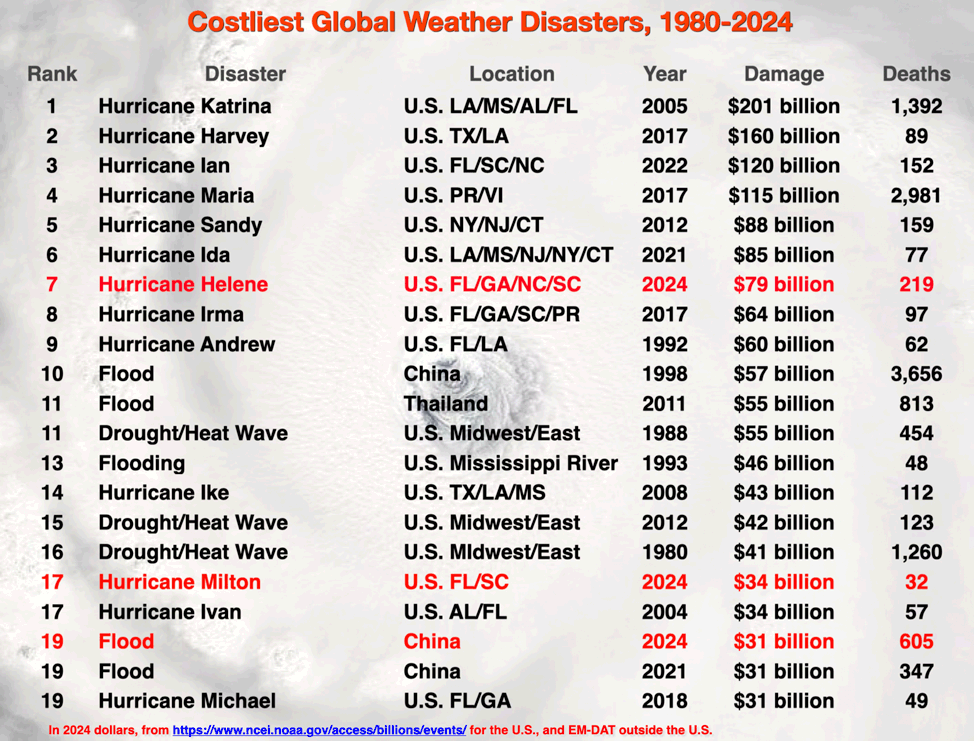

Three Top-20 Costliest Weather Disasters in World History in 2024: Hurricane Helene, Hurricane Milton, and Flooding in China

The year’s most destructive weather event of 2024 was Hurricane Helene, which made landfall in Florida’s Big Bend region September 26 as a Category 4 storm with 140 mph winds. As documented by Michael Lowry, at least 243 people lost their lives in Helene across seven states, making it the deadliest hurricane to hit the mainland U.S. since Hurricane Katrina killed an estimated 1,392 people in 2005. Flood damage from the hurricane was catastrophic in western North Carolina, and the $79 billion price tag makes it the seventh-most expensive weather disaster in world history, adjusted for inflation.

The second costliest weather disaster of 2024 was another U.S. hurricane, Category 3 Milton, which made landfall near Sarasota, Florida, and cost $34 billion. Seventeen of the top 20 most expensive weather disasters in world history are U.S. events, with two of these occurring in 2024.

Researchers at the Imperial College of London separately determined that climate change increased Helene’s wind speeds at landfall by about 13 mph or 11%, and Milton’s by almost 11 mph or 10%. Using a previously published damage function and data on the exposed value of global assets, the researchers determined that 44% of the economic damages caused by Helene and 45% of those caused by Milton could be attributed to climate change. They added that the analysis “likely underestimates the true cost of the hurricanes because it does not capture long-lasting economic impacts such as lost productivity and worsened health outcomes.”

China suffered $31 billion in damages from summer flooding during 2024. This was Earth’s third-costliest weather disaster of 2024 and is tied with the summer 2021 floods as China’s second-costliest weather disaster on record. Their costliest weather disaster occurred in 1998 when river flooding killed 3,556 and caused $57 billion in damage. This disaster ranks as the costliest weather-related disaster in world history to occur outside of the U.S.

The radar in #Haikou is centered in the eye of powerful #TyphoonYagi… and thankfully it’s still up & running (so far)!! 🤞https://t.co/pK3EMVUtlw pic.twitter.com/kcGhE6XgSx

— Brian McNoldy (@BMcNoldy) September 6, 2024

Fourth-Most Expensive Typhoon on Record: Yagi, $16.8 billion in Damages

After peaking as a Category 5 super typhoon with 160 mph winds, Typhoon Yagi made a devastating landfall on China’s Hainan Island as a Category 4 storm with 150 mph winds on September 6, 2024, causing over $11 billion in damage in China. Yagi made a subsequent landfall on September 7 in Vietnam as a Category 4 storm with 130 mph winds, making it that nation’s strongest typhoon since modern records began in 1945. Yagi caused $3.3 billion in damage in Vietnam – the country’s costliest typhoon on record. Overall, Yagi’s $16.8 billion in damage made it the world’s fourth-costliest typhoon on record (using statistics from EM-DAT, inflation-adjusted to 2024 dollars). Here is their top-10 list of most expensive typhoons:

1) $25 billion, Doksuri, 2023 (China)

2) $22 billion, Mireille, 1991 (Japan)

3) $20 billion, Hagibis, 2019 (Japan)

4) $17 billion, Yagi, 2024 (China, Vietnam, Philippines, Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, India)

5) $15 billion, Jebi, 2018 (Japan)

5) $15 billion, Songda, 2004 (Japan)

7) $12 billion, Lekima, 2019 (China)

8) $11 billion, Faxai, 2019 (Japan)

9) $9 billion, Fitow, 2013 (China)

9) $9 billion, Flo, 1990 (Japan)

9) $9 billion, Bart, 1999 (Japan)

This list leaves out what was possibly the most destructive typhoon of all time, Typhoon Nina of 1975. Nina stalled out and dumped prodigious rains for two days in the Ru River drainage basin upstream of the Banqiao Dam, leading to the dam’s collapse and the loss of 171,000 lives, with an area 34 miles long and eight miles wide wiped out. The disaster was not disclosed by China until the mid-1990s. The list above also does not include the $12 billion flood disaster in southern Japan in July 2018, which was caused by the presence of a stationary seasonal frontal boundary enhanced by remnant moisture from Typhoon Prapiroon.

A Record Year for Heat Waves: Three With at least 1,000 Deaths

Earth’s hottest year on record brought three heat waves that killed at least 1,000 people in 2024. The more than 9,000 deaths that occurred during the summer heat wave in Europe ranks as the year’s deadliest weather disaster and is the fifth-deadliest heat wave in world history. In addition, 1,301 heat wave deaths occurred in Saudi Arabia June 14-19 during the Hajj, when temperatures exceeding 50 degrees Celsius (122 °F) occurred. And the last group of more than 1,000 heat wave deaths occurred in the U.S.; most of these were in Maricopa County, Arizona (home of Phoenix), which reported 657 heat wave deaths. Aon lists another 2024 heat wave that occurred in Southeast Asia April 20-May 5, which killed 1,571 people; Gallagher Re lists only 111 deaths for that event.

Before 2024, there were only 18 heat waves in history documented by EM-DAT to have killed at least 1,000 people; 2024 would be the first year to have three entries on this list (assuming that the EM-DAT database, which has not yet updated its heat wave numbers for 2024, agrees with Gallagher Re’s numbers). Note, though, that heat wave deaths are often not fully quantified until several years after the event and are often drastically underreported.

For example, in 2022, Maricopa County, Arizona, which contains Phoenix, reported 425 heat-associated deaths. Yet EM-DAT lists only 136 heat wave deaths for the entire U.S. for that year, and NOAA lists just 383. Officials in Maricopa County and some other areas are now making more concerted efforts to account for all heat-related deaths; this will lead to more accurate totals going forward but will add to the challenge of apples-and-apples comparisons between recent and long-ago heat waves.

>Earth’s Fifth-Deadliest Wildfire on Record: 137 Killed in Chile

Earth’s hottest year on record intensified multiple destructive and deadly wildfires in 2024. The deadliest was a horrific wildfire, fueled by near-record drought, extreme heat, and El Niño, which swept through the coastal city of coastal city of Viña del Mar, Chile, on February 2-3. The death toll of 137 makes this Earth’s fifth-deadliest wildfire since 1900, and the $1 billion price tag makes it Chile’s second billion-dollar weather disaster on record. (The other was a 2015 flood that cost $1.9 billion, adjusted for inflation.)

The World Weather Attribution group could not identify a climate change influence on the 2024 Chile wildfires. But according to a 2024 study, six out of seven of Chile’s most destructive fire seasons on record occurred since 2014, and the study authors stated, “the concurrence of El Niño and climate-fueled droughts and heat waves boost the local fire risk and have decisively contributed to the intense fire activity recently seen in central Chile.”

🔴#ViñaDelMar| Recorrido aéreo de @AFPespanol evidencia la devastación en la zona por incendios forestales. pic.twitter.com/H2ymbUozK8

— Fernando Ulloa Galaz (@UlloaG_Fernando) February 4, 2024

An Increase in “Hot Droughts” Worldwide

Many parts of the world are experiencing a shift toward “hot droughts”: droughts associated with less precipitation than average combined with significantly above-average temperatures — a double whammy that greatly increases the risk of ecosystem impacts and destructive wildfires. This is the kind of drought that affected Chile during its catastrophic wildfires in both 2023 and 2024 and has increasingly been affecting California. A 2024 study published in the Journal of Arid Environments concluded, “Our findings support the idea that anthropogenic warming results in a changing drought climatology for arid and semiarid regions of southern California and that hot droughts will likely become the dominant drought type.”

Fortunately, global losses from drought were below average in 2024, according to Aon, which listed $18 billion in losses. This is well below the 2000-2023 average of $40 billion per year.

A Concerning Increase in Deadly Wildfires Globally

Five of the top 10 deadliest wildfires globally since 1900 have occurred since 2018, according to statistics from EM-DAT. This worrisome trend results not only from climate change but also from an increase in the number of people moving into fire-vulnerable areas — the wildland-urban interface, often called the WUI. In addition, poor land management practices have contributed to extreme wildfire activity; for example, in Chile and Portugal, recent catastrophic fires burned through plantation forests densely packed with fire-vulnerable trees. In some regions, fire-prone invasive plants have been a problem, such as in the wildfire that consumed Lahaina, Hawai’i in 2023, killing 102 people. Finally, human-caused ignition sources have increased as more people and more infrastructure push into forested areas.

The flood situation in Nigeria is off the scale. Just Horrific 😭pic.twitter.com/rGi3QcI0j8

— Volcaholic 🌋 (@volcaholic1) September 17, 2024

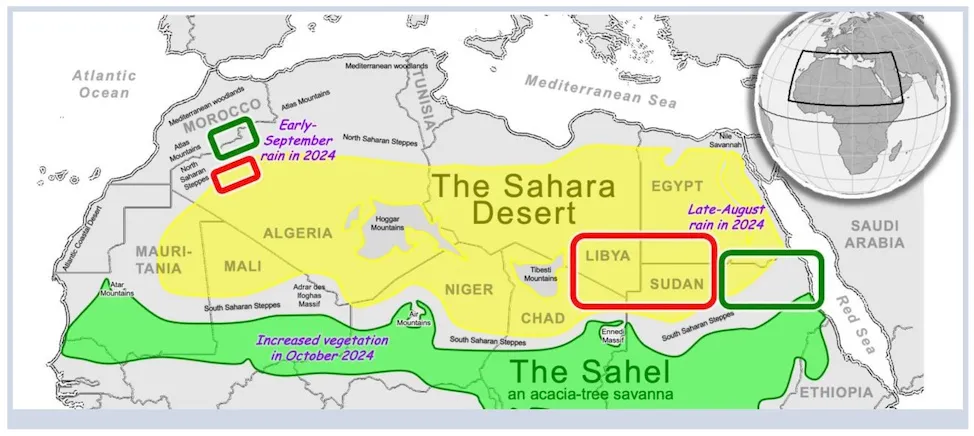

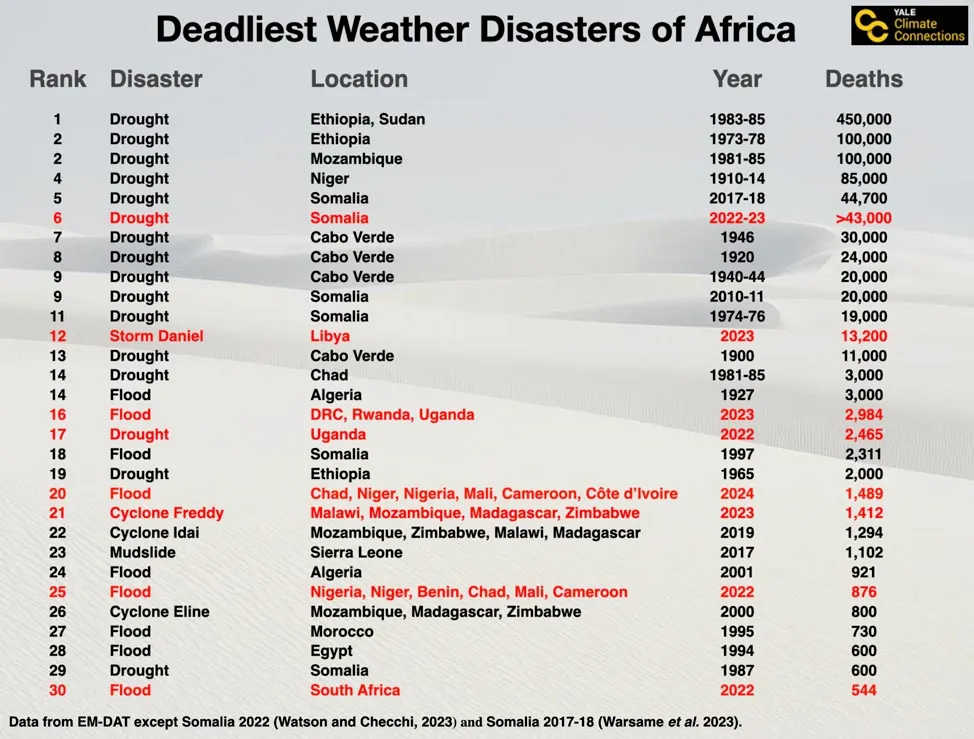

A New Addition to the Unprecedented Number of Very Deadly African Weather Disasters Since 2022

Torrential rains during July, August, and September 2024 unleashed catastrophic floods in West and Central Africa, affecting over 4 million people in 14 countries: Benin, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and Togo. According to the U.N. World Food Program, the floods exacerbated a regional hunger crisis that was already affecting 55 million people – four times more people than five years ago. EM-DAT lists 1,489 flood deaths for 2024 in those nations, primarily in Chad, Nigeria, and Niger. These floods affected the same area that experienced catastrophic flooding in 2022 that killed 876 people. However, this year there was also significant rain and flooding even further north, extending from the semiarid Sahel region into the Sahara Desert itself, as observed by NASA satellites. Some parts of Libya and Sudan received up to 5 times their normal annual rainfall.

Figure 5. Areas of North Africa that received notable rainfall in August and September 2024. (Image credit: NASA Global Precipitation Measurement)

According to an analysis by the World Weather Attribution group, human-caused climate change made the 2024 floods about twice as likely to occur and 10% more intense. For the 2022 floods, the group said human-caused climate change made the event about twice as likely to occur and 5% more intense.

Despite recent improved weather forecasting technology and increased disaster awareness and preparation efforts, the African continent has suffered an unprecedented number of deadly weather-related disasters over the past three years. The 2024 floods are the eighth weather-related disaster to kill at least 500 Africans since 2022, and an astonishing 27% of the continent’s 30 deadliest weather-related disasters since 1900 have occurred since 2022 (Fig. 6).

This ominous figure could well be a harbinger of the future, as higher vulnerability, a growing population, and more extreme weather events from climate change cause an increase in deadly disasters. For more detail, see our September 13, 2023, post on Storm Daniel, “The Libya floods: a climate and infrastructure catastrophe.”

The scale of the flooding in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil is unfathomable!!!! pic.twitter.com/pmLpJpTz9C

— Volcaholic 🌋 (@volcaholic1) May 8, 2024

Special Weather Whiplash of 2024 Awards: Brazil and Spain

Brazil: Not only did Brazil suffer its costliest weather disaster on record in 2024 — the $14.5 billion in damage from the Rio Grande do Sul floods — the nation also suffered $6 billion in losses from drought and had massive fires that burned an area the size of Italy — the largest area on record — in the Amazon.

Spain: In late October, torrential rains hit eastern Spain, triggering catastrophic flooding that killed 231 people and did $12 billion in damage, primarily in Valencia. The flood ranks Spain’s costliest weather disaster on record and is Europe’s 10th-costliest weather disaster in history. The 231 deaths also made it the 10th-deadliest flood in European history (and third-deadliest in Spanish history). Spain also suffered $3.2 billion in drought losses in 2024 and was one of the four nations most affected by Europe’s summer heat wave, which killed over 9,000 people.

One other nation suffered its costliest inflation-adjusted weather disaster in history during 2024: the United Arab Emirates, with $7 billion in damage from the Persian Gulf flash floods of April 2024. In addition, the French territory of Mayotte had its most expensive disaster on record in 2024, from catastrophic category 4 Cyclone Chido, which caused insured losses of $675 million, and total losses that could rival the nation’s GDP of $3 billion, according to Aon.

For comparison, seven nations had their most expensive weather-related natural disaster in history in 2023. Note that these tallies will be considerably different using Aon or Gallagher Re disaster figures, which can differ from EM-DAT’s by a factor of two. Gallagher Re’s database is generally superior to EM-DAT’s but is not publicly available.

With everywhere flooded in Dubai, they still have constant electricity. 🙏🏽🙏🏽 https://t.co/RbFdPZUDL7

— Name cannot be blank (@hackSultan) April 18, 2024

Bob Henson contributed to this post.

My county just received another 5 million dollars to pay for final sweep wood pickup. For us, at least, Helene has been an unprecedented disaster. And a few years back a tornado swept through the town (and barely missed my house) which was also a first.

But the last book I read was about the Galveston hurricane of 1900 which destroyed the city and is still, apparently, considered the strongest hurricane ever to hit the US. Nature is capricious and that’s not a new thing.

Deadliest, not stongest. It was a Cat 4.

And a lot of the deaths were snakebites – which is not as much of a problem in modern storms because people aren’t climbing into trees to escape flood water.

Similarly many recent APAC disasters were probably less costly because of new infrastructure (especially for earthquakes which are not – absent fracking – usually considered climate change.)

I believe the book said it’s unclear how powerful the winds really were since measurement instruments were destroyed by the storm.

But perhaps one can at least say that the frequency of these weather disasters is increasing if not necessarily their power. And snakes may be less of a problem but a larger population being in harms way is no doubt more.

I don’t envy any of the actuaries at any property insurance companies these days. The problem being relative to climate change is that “weather events” need to be predictable, at least statistically. For example, some people, including climate change deniers, like to point out that the disaster effects of Hurricane Helene are not new and have been experienced before. While that may be true, if I’m an actuary at an insurance company there is a big difference between a weather event like Helene happening every 100 years and then this thing called climate change makes it every 75, 50 or even every 25 years. AND even if we agreed a weather event like Helene will happen more frequently, we have little to no real data to work from for predicting what the eventually probabilities of it happening again are and then adjusting investments and policy rates accordingly.

I’d speculate that the next decade is going to produce some major retrenching in property insurance offerings as the payouts from climate change impacted events exceed the current preparedness of these companies.

Independent report on bad economic conditions in Europe

Survival Lilly, an Austrian, living in a forest in Germany and broadcasting from her car

She holds up her cell with photos of articles which she discusses

I was shocked to hear about conditions for the poor in Austria.

She has 1.5 M subscribers and “Situation in Europe, Part I” , 2 weeks ago, 96 K views, 2 K comments

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3uuzAjw6Mzk

In Situation in Europe Part II she begins with the cost of a family of 4 for a lift ticked for a day is 200 Euros. Does not include food. She then goes into the cost of vegetables. For me, this shows the collapse of the economy of Europe hastened by the Ukraine war.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LYXyeVf_G3Q

Imo 58b is far too low.

The Ca fires are guessed at 50b alone. Our rainy season usually starts in Nov, ending the fire season that usually begins in September. Heavy rains last year helped protect from fires through last fall, but by years end everything was dry as tinder, imo likely much drier than it gets in normal years. If we’d had normal rainfall this season the fires wouldn’t have been anything like they were. Is this gw?

Just an anecdote, but my first year here in 75 a married guy invited the recently transplanted bachelors over for thanksgiving. It rained cats and dogs that day, hard as an eastern storm.

While the Palisades and Altadena fire destruction began in the peripheral dry wildlands, the progression through the suburban core was perpetuated by high-winds igniting combustible homes that were mostly no more than 10′ apart. Those homes ignited and became engulfed in less than 10 minutes for each structure. Remove the wind and municipal fire departments can handle a few homes on fire simultaneously–not the firestorm that occurred. The actual 70MPH winds were the reason for the minimum $50B in losses.

While there is great concern about Climate Change, our Fuhrer has assured us that its all fake, and we can rest easy. But as an old sceptic, I’m not feeling quite so much at ease. These next 4 years, with our withdrawal from climate accords, and the like, might prove to be the final straw. We don’t have endless amounts of time to try to keep the planet from boiling over, but we appear to be content to keep kicking the can down the road. Its hard to tell what will wake us up before its too late.

I think Trump will cause all sorts of problems.

Solar will continue in the US because it’s cheaper. Just like fracked gas lower cost is what killed coal.

The rest of the world is buying inexpensive Chinese solar equipment.

We thanks to Biden have the most expensive solar panels due to tariffs. And I’m sure Trump will follow.

My point is the rest of the world lead by China is moving forward.

Thank you for this! Climate change is a multiplier and it is upon us. The thoroughness of Jeff Master’s (and Bob Henson’s), in their depth, presents an economic overview, they prudently do not forecast what lays ahead. It will be worse than their present observations. I dwell upon future conditions for life on this earth, and for the prospects for humanity.

Is there some kind of Weather Disaster Swap (WDS) that I can buy, preferably with zero upfront payment and generous margin financing terms? Since no one’s going to do s***, might as well profit from the phenomenon, no?

In related rates, values rise faster than inflation, so these $billion disasters will be persistently becoming more frequent. In my kids’ lifetimes they will be ordinary. We need a different measure.

There are about 9,000,000 households inFlorida. Using the 45-year period since 1980, I guesstimate about $280 billion in losses for Florida over that period, about 6.22 billion average annually. That wouldn’t be more than $1000 per household.

Looking at last year, I’d guess about 50 billion, assigning all the cost of Milton to Florida and about 15 billion for Debby and Helene. That comes to an average of $5555 per household. Obviously bigger houses caused more of the claims.

The real killer was Ian which drove a wall of water into the Gulf Coast in 2022, causing 3x the damage of Milton. If a year is only as bad as 2024 on average, the cost of homeowner’s insurance will break the housing market there.