We wrote some years back that there were seriously rotten things afoot in unicorn-land and venture capital generally. That assessment is now borne out by a new Bloomberg story by Kate Root, The Unicorn Boom Is Over, and Startups Are Getting Desperate, touted by Bloomberg’s Matt Levine in The Unicorns Are Zombies. The short version is that not only did nearly all of these once hyped companies fail to make exits (then expected to be via IPO) and seem pretty certain to be unable to do so now at deemed-adequate prices, but many look set to eventually have to shut operations or radically downsize.

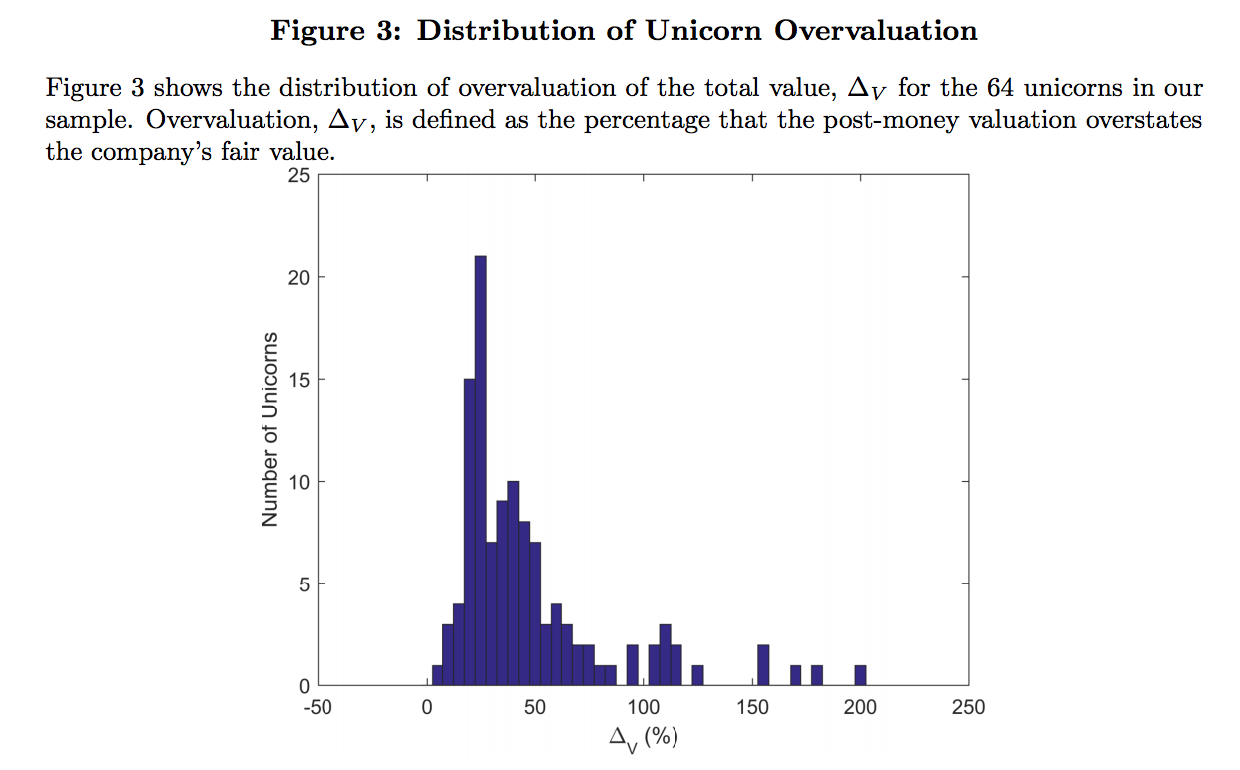

The reason this is no surprise is that investors conned themselves in the unicorn bubble. For instance, from a 2017 post, Fake Unicorns: Study Finds Average 49% Valuation Overstatement; Over Half Lose “Unicorn” Status When Corrected, based on the in-depth work of economists Will Gornall and Ilya Strebulaev, we unpacked the wild overvaluation of unicorns.

And by wild overvalution, we did not mean investors being willing to pay more than even an optimistic reading of their prospects suggested. This instead was a remarkable failure of basic competence: of investors using flattering valuation rules of thumb as opposed to analyzing what various of the multiple classes of equity of privately issued equity were worth. From that post:

A recent paper by Will Gornall of the Sauder School of Business and Ilya A. Strebulaev of Stanford Business School, with the understated title Squaring Venture Capital Valuations with Reality, deflates the myth of the widely-touted tech “unicorn”. I’d always thought VCs were subconsciously telling investors these companies weren’t on the up and up via their campaign to brand high-fliers with valuations over $1 billion as “unicorns” when unicorns don’t exist in reality. But that was no deterrent to carnival barkers would often try to pass off horses and goats with carefully appended forehead ornaments as these storybook beasts. The Silicon Valley money men have indeed emulated them with valuation chicanery.

Gornall and Strebulaev obtained the needed valuation and financial structure information on 116 unicorns out of a universe of 200. So this is a sample big enough to make reasonable inferences, particularly given how dramatic the findings are.1 From the abstract:

Using data from legal filings, we show that the average highly-valued venture capital-backed company reports a valuation 49% above its fair value, with common shares overvalued by 59%. In our sample of unicorns – companies with reported valuation above $1 billion – almost one half (53 out of 116) lose their unicorn status when their valuation is recalculated and 13 companies are overvalued by more than 100%.

Another deadly finding is peculiarly relegated to the detailed exposition: “All unicorns are overvalued”:

The average (median) post-money value of the unicorns in the sample is $3.5 billion ($1.6 billion), while the corresponding average (median) fair value implied by the model is only $2.7 billion ($1.1 billion). This results in a 48% (36%) overvaluation for the average (median) unicorn. Common shares even more overvalued, with the average (median) overvaluation of 55% (37%).

How can there be such a yawning chasm between venture capitalist hype and proper valuation?

By virtue of the financiers’ love for complexity, plus the fact that these companies have been private for so long, they don’t have “equity” in the way the business press or lay investors think of it, as in common stock and maybe some preferred stock. They have oodles of classes of equity with all kinds of idiosyncratic rights. From the paper:

VC-backed companies typically create a new class of equity every 12 to 24 months when they raise money. The average unicorn in our sample has eight classes, with different classes owned by the founders, employees, VC funds, mutual funds, sovereign wealth funds, and strategic investors…

Deciphering the financial structure of these companies is difficult for two reasons. First, the shares they issue are profoundly different from the debt, common stock, and preferred equity securities that are commonly traded in financial markets. Instead, investors in these companies are given convertible preferred shares that have both downside protection (via seniority) and upside potential (via an option to convert into common shares). Second, shares issued to investors differ substantially not just between companies but between the different financing rounds of a single company, with different share classes generally having different cash flow and control rights.

Determining cash flow rights in downside scenarios is critical to much of corporate finance, and the different classes of shares issued by VC-backed companies generally have dramatically different payoffs in downside scenarios. Specifically, each class has a different guaranteed return, and those returns are ordered into a seniority ranking, with common shares (typically held by founders and employees, either as shares or stock options) being junior to preferred shares and with preferred shares that were issued early frequently junior to preferred shares issued more recently.

In other words, unlike the hopefully very liquid shares of public companies that many own, all fungible with those of other stockholders, each class of equity in these unicorns is bespoke, with different rights in the case of investment success and shortfall.

We teased out further implications of the Gornall/Strebulaev analysis in a 2018 New York Magazine article, Fake ‘Unicorns’ Are Running Roughshod Over the Venture Capital Industry. From that article:

You might think that a study demonstrating that venture capital-funded “unicorns” are overvalued, and by a stunning 48 percent on average, would shake up the industry. Yet “Squaring Venture Capital Valuations With Reality,” a paper announcing just that finding by Will Gornall and Ilya A. Strebulaev (professors at the Sauder School of Business at the University of British Columbia and the Stanford Graduate School of Business, respectively), received only a perfunctory round of coverage from some important investment and tech publications when it was published.

It’s no surprise that a study casting doubt on the worth of darlings like Lyft and Cloudflare didn’t move investors or change the venture capital industry. Trade press reporters don’t have much of a future if they take to biting the hands that feed them, and the investors with overpriced wares don’t want to admit they’ve been had, or, worse, that they’re part of the problem. But write-ups of this important paper, with its sensational finding, missed that the authors’ analysis is deadly for the venture capital industry as a whole.

The median venture capital fund loses money. Only the top 5 percent of funds earn enough to justify the risks of investing in venture capital. The nature of venture capital is that the performance of those few successful funds in turn rests on the spectacular results of a small fraction of the investments in a particular fund. Gornall and Strebulaev’s finding that the performance of the winners — and even the also-rans — is overstated further undermines the already strained case for investing in venture capital. If you are Joe Retail and think this isn’t your problem, think twice. If you invested in high-growth mutual funds, your holdings probably include shares in large venture-capital-backed private companies.

And now the caliber of the downside protection in these supposedly well-negotiated classes of private stock are about to be tested. Key sections from the Kate Root Bloomberg account:

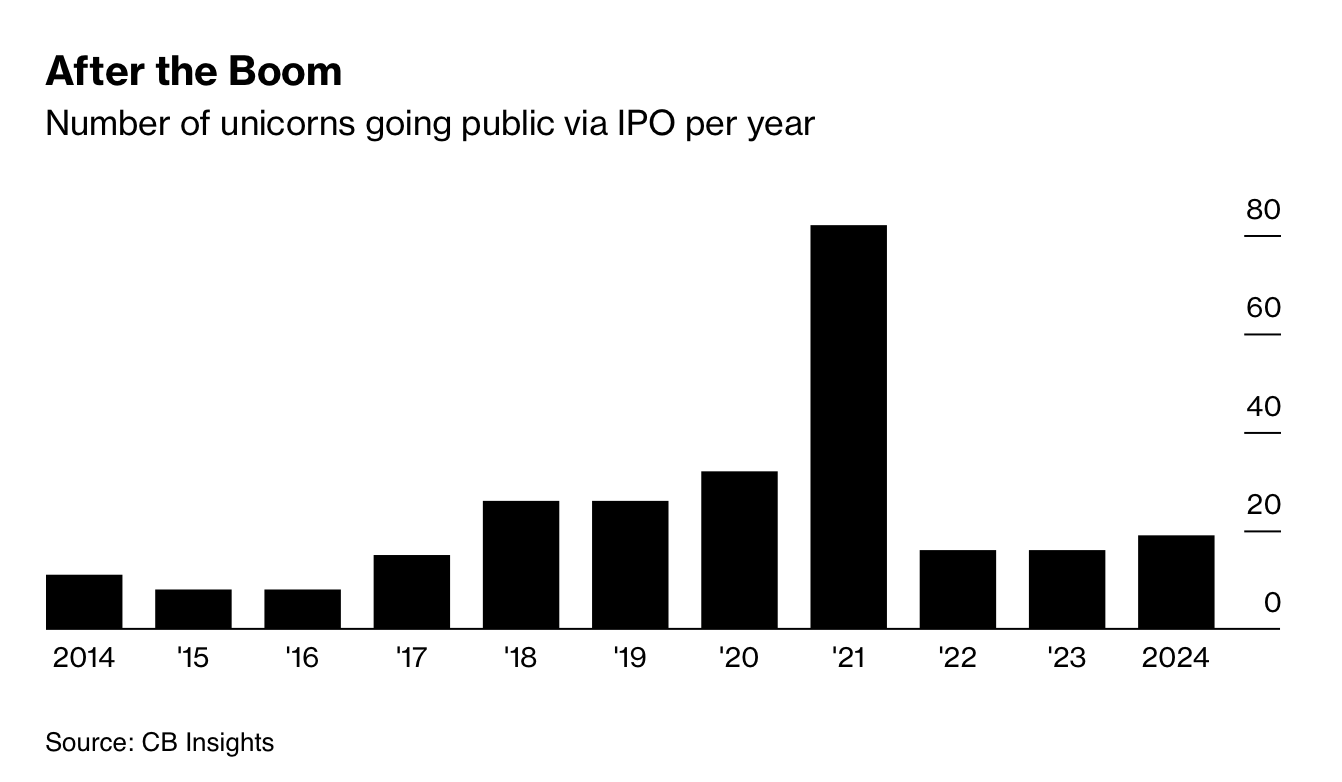

By the time the Covid-era tech boom crested in 2021, well over 1,000 venture capital-backed startups had reached valuations above $1 billion, including fake meat purveyor Impossible Foods Inc., home maintenance marketplace Thumbtack and online-class platform MasterClass. Then came a squeeze sparked by rising interest rates, a slowing initial public offering market and the feeling that any startup not focused on AI was yesterday’s news….

In 2021 more than 354 companies received billion-dollar valuations, thus achieving unicorn status. Only six of them have since held IPOs, says Ilya Strebulaev, a professor at Stanford Graduate School of Business. Four others have gone public through SPACs, and another 10 have been acquired, several for less than $1 billion. Others, such as the indoor farming company Bowery Farming and AI health-care startup Forward Health, have gone under. Convoy, the freight business valued at $3.8 billion in 2022, collapsed the following year; the supply chain startup Flexport bought its assets for scraps….

Welcome to the era of the zombie unicorn. There are a record 1,200 venture-backed unicorns that have yet to go public or get acquired, according to CB Insights, a researcher that tracks the venture capital industry. Startups that raised large sums of money are beginning to take desperate measures. Startups in later stages are in a particularly difficult position, because they generally need more money to operate—and the investors who’d write checks at billion-dollar-plus valuations have gotten more selective. For some, accepting unfavorable fundraising terms or selling at a steep discount are the only ways to avoid collapsing completely, leaving behind nothing but a unicorpse.

“Unicorpse”! Continuing:

Many startups, though, were built to chase growth with little concern for near-term profitability in their early years, assuming they could continue fundraising at increasing valuations. In many cases, that formula no longer works. Fewer than 30% of the unicorns from 2021 have raised financing in the past three years, according to data provided by Carta Inc., a financial technology company working with startups. Of those, almost half have done so-called down rounds, where investors value their companies at lower levels than they’d received in the past.

One of the big risks of the enthusiasm for venture capital was the assumption that the market for IPOs which provide valuation benchmarks for other exits, would remain accessible. Protracted super low interest rates resulted in investors reaching for return, and thus risk, which was not a sound investment proposition if you didn’t get out before the window of permissiveness closed. When I was a kid at Goldman, the rule of thumb was that the IPO market was accessible to young technology companies only about two years out of five, so that venture-backed plays needed to have enough cash or access to funds so as to catch those opportunities.

And please do not attempt to defend venture capital firms. Fewer than 1% of startups get venture funding, according to the careful work of Amar Bhide. And they weren’t essential to the performance of the highest-growth companies. One of my past lawyers, who represented a lot of inventors, strongly advised them to get money anywhere other than venture capital: friends, family, vendors, customers. She’d seen too many of the original managements teams have their companies taken from them by the moneybags. In keeping with her view, only 25% of the Inc. 500 was venture capital funded. And that total includes quite a few cases where the high-growth private company had grown big enough to do an IPO, but investment bankers recommended a late venture capital funding round. Being able to tout top names like Kleiner Perkins or Sequoia as backers would produce a higher valuation, enough to offset the dilution of a share sale.

And let’s not forget that venture capital is not a good deal for limited partners either. From a 2023 post, “Venture Capital Funds Are Mostly Just Wasting Their Time and Your Money”:

This deliciously-titled Financial Times story recaps a new study by Morgan Stanley equity strategists Edward Stanley and Matias Øvrum which provides a devastating takedown of the venture capital industry’s claim to making money for investors, as opposed to just themselves. The overarching finding is that venture capital funds typically don’t outperform stocks, and that’s before getting to the fact that it is pretty much impossible to pick venture capital winners (more on that shortly). Oh, and because venture capital is riskier than investing in equities, investors oughts to get better returns than if they just bought some index funds.

Mind you, this is hardly a new idea. The Economist pointed out some years ago, based on a different large-scale study, that venture capital funds only meet equity returns with a lot more fees and risks. Harvard professor Josh Lerner said as much in a 2015 presentation to CalPERS’ board, except he pointed out that to the extent the industry could claim to outperform, it was in the top 10% of the funds. Lerner insinuated that there might be a secret sauce for that; a one-time newbie on the HBS faculty had Lerner tell him how to get lucrative consulting gigs advising public pension funds on this Mission Impossible. As we wrote in 2014:

When you boil it down, this graph illustrates the ugly truth of investing in private equity: it’s not attractive unless you can outrun most of your peers investing in the asset class.

Rather than question the logic of investing in private equity at all, everyone in the industry has convinced themselves that it is reasonable to believe that they can be the Warren Buffett of private equity. The investment consultants go through the shooting-fish-in-a-barrel exercise of convincing their institutional clients that each of them is prettier, smarter, and more charming than average, and therefore capable of achieving sparking results. Needless to say, flattery is an easy sell…

Fundamentally, this is an intellectually dishonest exercise, and diametrically opposed to the way many public pension funds construct other parts of their investment portfolios. With public equity in particular, it’s almost certain that a significant majority of U.S. pension fund assets are invested in index funds. That’s because pension funds have recognized that, collectively, they cannot do better than average, and that after paying active management fees, actively managed public equity portfolios typically perform worse than the market average.

So it’s not as if these investors are so clueless that they can’t grasp the point that all of them cannot achieve above average results, let alone significantly above average results. Instead, with private equity, there is a desperate desire to be in the asset class for reasons that probably reflect a combination of intellectual capture by the PE managers, political corruption in legislatures that control public fund board appointees, and the need to have a strategy that could conceivably solve the pension underfunding problem over time.

Mind you, the “see if you can out-invest your competitors” problem is more acute in venture because outperformance is concentrated in so few funds.

Why are we belaboring this history before getting to a juicy paper? Because the bad facts about venture capital are, or should be, well known. But it’s just so much fun to talk to those venture capital mavens about all the great sexy things they invest in, even if the vulture, um, venture capitalists spend too much money finding and baby-sitting their charges, and most come a cropper anyhow.

Investors really do fall sucker to private equity and venture capital patter about their big game hunting of companies (and the remarkable investor permissiveness in allowing them to assign their own valuations of investee companies). Notice how hedge funds have to some degree fallen out of favor due to what ought to be recognized as the same basic problem, too much fee and expense extraction relative to any ability to outperform (“generate alpha”)? That’s because private equity and venture capital partners and sales staff are charismatic and manipulative, while really good hedges are often geeks. And even when not, it’s hard to make an explanation of your quant-y investment method sound sexy. Instead, hedgies tend to induce MEGO (“My Eyes Glaze Over”), which is hardly an inducement for writing big checks.

So even though investors have had decades to figure this scam out, it remains an exercise in hope over experience.

No surprise that Unicorns require a steady diet of ZIRP brand alfalfa. Also no surprise that, upon leaving the era of zero interest rate policy, the investment advisor class turns out to be less talented than advertised.

Thanks for “unicorpse”. I guess we know what marketing is having for lunch.

Oh well, they surely moved fast and so it goes, that in a like manner they can also close fast. I have a sibling whose start up IT tech firm has basically never gained or generated compound growth in revenue, or if the firm somehow caught the right moment that moment was perhaps fleeting. As in, mid year 2007 it seemed quite healthy and decent trending growth…but alas what came next was most certainly not an optimal economy in 2008 to 2010. Keeping the lights on and doors opened for this firm’s small business customer base takes commitment and effort these past 25 years.

There is no market for the Juicero! For shame! \sarc

Ah yes Juicero the poster child of VC Hubris. Build a hilariously over engineered $2000 machine to squeze a juice pak. Said paks sold as a subscription at eye wateringly high prices.

I first became aware of Juicero watching a teardown video of a machine.

It seems like there is a decent amount of comedy and entertainment value, and perhaps educational value as well, in the stories of failed unicorns. Has anyone tried to systematically compile a set of these tales that would make for easier reading?

(We already have the Mayday documentary that chronicles airplane crashes, so it seems like there is a good precedent…)

To say this is damning and obvious is an understatement. As has been frequently raised here, how can endowments, institutional investors, etc. possibly explain providing VCs money?

Having only seen a VC/PE return numbers as an insider a few times, I had to point out to my powers-that-be that the returns were all predicated on a few anomalous factors. First and foremost is that 1, or 2, outsized successes out of a large portfolio is randomness, not skill, and certainly not repeatable. Second, in PE a lot depends in buying at a low-ebb in valuation, and then having valuation multiples rebound, which again is luck not skill. To a firm that has to state in all its literature that past results are not a predictor of future results, when they got the gleam in their eyes to rub shoulders with brand name VC/PE titans they couldn’t wait to pour our investors money in. I resigned. It didn’t work out for the investors.

I would not be surprised if there is some form of “payola” between VCs, companies, and media….beyond the standard “access to interviews and scoops payola”.

Financial journalism has crashed into the gutter over the last 10 years. Makes the CNBC staff from 1999 all look like Walter Cronkite.

Yeah my eyebrows are raised too. The former CEO of Hillary’s Blinds (the main company round here) bought the lion’s share of his house blinds etc (*cough*mansion?*cough*) from my Dad’s company, not the company he’d led and “nurtured” for years and which is now VC owned (I have a comment in moderation about the background to this industry).

Why? I dunno and make no insinuations but it certainly appears odd and begs questions.

I won’t comment on PE, it is financial engineering that assumes the existence of a business as its foundation, but I can comment on venture capital because it is what I do for a living (especially as the all grass and no cattle farm is going on the market).

The article is entirely correct about the VC unicorns being stranded. It is also correct about the public misrepresentation of their value, which at the simplest was to apply the price per share of the latest most favoured share class to all of the shares in issue, despite these having inferior rights, and claiming the resulting inflated number as the valuation.

What is not clear from the excerpts (the article is paywalled) is whether this misrepresentation of the companies’ value was ever used to induce an investor to invest. It was certainly used as public marketing of a company’s “success”/” hotness” but even funds that seem prey to strategic idiocy (mentioning no names, Softbank!) are full of tactically smart people who know how to read an equity waterfall and calculate the real value of the latest class of shares. And no venture fund would be allowed to get away with valuing common stock or lower ranking preference classes at the pps of the highest class when it valued its holding. IFRS9 etc is very clear about valuation methodology. If any fund has done this, there will be consequences….

Where funds have likely marked their own homework favourably is in valuing the unicorn as a whole. This is ultimately a matter of judgment. If the fund is not audited, there will be no challenge to the general partners, to take a provision for market conditions (recent comparables, public market multiples) or portfolio company performance against business plan or budget. An inflated valuation cascades down the waterfall of different stock classes – a rising tide lifts all boats – and thus maintains or inflates the fund’s fair value if its holdings. So I imagine that mechanically the Series A, B, C is correctly valued but the top-level input from which the value is calculated is fantastical.

As for the unicorn epithet, it has been a common phrase of mine for twenty years (and immediately understood by other UK VC’s because we share an idiolect, like any niche industry) to describe those funds with venture capital positioning but private equity investment instincts (i.e. funds who want a business with cheap entry price and high upside potential but low risks and modest cash investment requirement) as not looking for zebras (a rare equid) but for unicorns (a non-existent one). It was my extension of the medical saying that when you hear hoofbeats, think horses not zebras (assume the most likely occurrence).

It has been very strange to live through ten years in which its public meaning was inverted as a badge of success for portfolio companies rather than a mark of shame for funds! Most of these unicorns will end up as dog food and glue because they can not raise money without investors taking huge write downs.

Finally, there IS some good in venture capital but not at the top end of the market. The late stage investors with £100m+ ticket sizes are looking for relatively modest returns (2x, say) but in a short timeframe (pre-IPO). These are the people funding the unicorns or investing in funds which do: the “private for longer” movement because ZIRP meant public market returns were too low and they diversified into private markets, just when insiders were looking to cash out. But “private for longer” meant VC valuations no longer had to converge on public market multiples.

These people are not the ones funding pre-revenue start ups or pre-profit growth companies. Even the unicorns had £mm revenues (and bigger loses). Without early stage VC, how would you form.and apply capital to disruptive new businesses? Even software companies have high start-up costs, despite cheaper development costs these days, and life science companies require ten or more years of ever increasing capital before you even know the product works!

Early-stage funds are usually small, $100m (VC management time doesn’t scale and early stage business can only absorb so much capital) and thus the fees won’t make anybody rich. Whereas the billion dollar multi-stage and late stage funds represent a ticket to wealth for the general partners even if the fund’s performance is poor, so the incentives are all blunted and it becomes asset gathering.

Quite how we keep the early-stage VC baby while we throw out the bathwater is a hard problem….

The article is not paywalled. I provided a link to an archived version of both Bloomberg stories.

And I have the entire paper underlying paper embedded in my post. Your claim about it is false. They showed for each and every unicorn for which they got the data that the valuations were NOT done from the value of the various classes of stock but a rule of thumb applied to the latest round. They have the goods and you are out of line to smear them. The paper is embedded at the link to my 2017 post. For your convenience: https://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2017/08/fake-unicorns-study-finds-average-49-valuation-overstatement-over-half-lose-unicorn-status-when-corrected.html

As I said, <1% of new businesses has VC funding. 3/4 of the Inc 500 did not and even the 1/4 that did included a pretty decent portion that were very last stage for valuation burnishing and not necessary to get to the IPO stage. You need to stop Making Shit Up. VC is not anywhere near as essential as you pretend.

As for your claim re early stage VC, that's terribly convenient since you can produce no data to show that it outperforms public stocks when adjusted for risk. I can ask Richard Ennis if he has seen anything that supports your view.

Exit liquidity:

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/private-equity-wants-a-piece-of-your-401k–and-hopes-trump-can-make-it-happen-090059639.html/

Private equity wants a piece of your 401(k) — and hopes Trump can make it happen

PE may need your 401K for life support. As of January M&A activity was at a many year low, and there aren’t a lot of debt-bomb exits being unloaded by PE firms these days…witness fund-of-fund shenanigans and continuations to keep their various ships afloat. Here we have a story stating that “Loans by banks to “non-depository financial firms” have soared from just over $50B in 2010…to nearly $1.2T in 2024”

https://www.ft.com/content/4a79657f-ad79-4cad-b044-db639ec8bdb4

It only takes one Creditanstalt.

The froth has moved from being liberally spread across the tech investment landscape to being concentrated in the AI tech investment corner of said landscape. OpenAI is in talks to raise $25bn at a $340bn valuation (while incurring $5bn in losses on $3.7bn revenue), Deepseek was meant to puncture the AI Capex investment thesis by showing an alternative path based on efficiency but alas the tech bros have successfully wrestled the narrative back to “we need to pour unGodly amounts of money at this technology otherwise our adversaries/China…” Unicorns crashing and burning will quickly be memory holed and hype will once again funnel capital into a hot sector, a bubble will form and subsequently pop, rinse and repeat. All this because VCs have managed to convince Americans that US competitiveness on the global stage depends on their unique capital allocation skills and as such they (and their industry) must be treated with reverence and given a free hand to speculate wildly on “the next big thing”.

VC and other “global investment firms” such as 3g Capital are always on the radar of my family. That group, in addition to a bunch of household brands you’d recognise, also bought out Hunter Douglas, the forrmer king of window blinds and shutters, who’d previously bought out the king of made-to-measure blinds in the UK and company my dad started out at, Hillary’s Blinds.

When my dad’s company was a viable competitor to Hillary’s in the 1980s/90s my school holiday job was taking telephone calls, arranging the scheduling of the guys who made sales and fitting calls across the East Midlands. It was a very taxing job. Thankfully my Dad reads similar stuff to me and saw the writing on the wall. Time to find a new market before VCs destroyed it. He now produces 99% Shoji blinds and room dividers – high mark-up low volume products – and gets perhaps one domestic call for a roller/venetian/vertical blind per week.

There are plenty of “franchisees” of Hunter Douglas/their new parent around but they never survive for long. As per the tech rather than manufacturing firms owned/controlled by these big companies the long-term markets are non-existent. Vimes’s rule of boots holds true with roller blinds sold at places like IKEA that enable you to cut down the (cardboard!) roller yourself.

Dad does 95% of his business in and around London to top end clients – one of them almost accidentally gave him the mobile number of the European head of a three-letter agency once (!) He was clever enough to see the writing on the wall in the 1990s and his workforce had to be reduced from 30+ to around 4. He now does work that VCs can’t copy cause it’s all skill/experience based and those are the contents of his head. Meanwhile we see the collapse of all the small manufacturers round here and only Keir Starmer wonders why the newly elected Labour MP is surprised that practically everybody hates him already. He was setting up a stall the other day in Sainsbury’s. I laughed internally and thought “you really need to get the shoppers at ASDA on your side but you’re probably afraid they’ll deck you”.

In the late 1990s, when I was an undergraduate engineer at a Silicon Valley feeder university, I learned VC were called vulture capitalists by the companies they were investing in. Turns out that VC were feeding more on their own investors.

As for the unicorns, most seem to be either Lovecraftian (successful) or undead (unsuccessful).

These startup founders could have “pivoted” and added the hottest buzzword of the day to their company name like say the Long Island Blockchain. 370% pop in a single day guaranteed. Do it every 6 months, and maybe, just maybe, instead of zombies, they could become Draculas!!