Yves here. This post, in analytical value, falls into the “History never repeats itself but it rhymes” category. It looks at a book ban campaign in China to see its impact on publication and self-censorship, and looks at what happened when the ban was lifted. It does offer the hope that things can revert to an old normal. Readers can hopefully look past the dig at Chinese censorship, which seems gratuitous in light of the Twitter files, the current Trump efforts to denigrate DEI even if it falls short of formal censorship, and efforts in the US and EU to stomp out anti-Zionist speech.

By Ying Bai, Ruixue Jia, Associate Professor at the School of Global Policy and Strategy, Co-Director of the China Data Lab University of California, San Diego, and Jiaojiao Yang, PhD candidate in Economics Chinese University Of Hong Kong. Originally published at VoxEU

Censorship, a widespread practice with a centuries-long history, has left a lasting imprint on languages around the world. In China, the “burning of books and burying of scholars” in 200 BCE marked an early instance of suppressing knowledge. In Europe, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, which was in effect from 1560 to 1966, served as a systematic effort to control what could be read and disseminated. Similarly, in the Soviet Union, the phenomenon of samizdat – self-publishing under censorship – became a means of resistance against state-imposed restrictions.

Understanding how censorship shapes knowledge production is critical for examining its broader political and economic implications. A bourgeoning literature on religious censorship in Europe highlights censorship’s detrimental effects – such as the setbacks experienced by banned authors and publishers (Becker et al. 2021, Blasutto and De la Croix 2023, Comino et al. 2024) – but important questions remain to be answered. How does censorship influence knowledge creation in general? What role does self-censorship play? If the power of censors wanes, could there be a permanent loss of knowledge due to decreased interest and availability in censored subjects, or might there be a revival?

In Bai et al. (2024), we explore these questions by studying the largest book-banning campaign in Chinese history, during the Qing dynasty’s compilation of the Siku Quanshu (Complete Library in Four Sections) from 1772 to 1783. Analysing over 161,000 book records spanning three centuries (1660s–1940s), we investigate the short-, medium-, and long-run effects of censorship on knowledge production and content. The significant political shifts over this period, including China’s forced opening to foreign powers in the 1840s, a major civil war from the 1850s–1860s, and the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911 provide a useful lens to investigate how knowledge producers – publishers and authors – adapted to shifting state power and control.

Historical Context and Research Methodology

The Complete Library, the most extensive book collection in Chinese history, catalogued over 13,000 books, including approximately 3,000 banned works. Heavily censored categories included history, imperial decrees and memorials, military strategy and conflicts, and various religions – topics seen as threatening to the Qing regime’s legitimacy. Unlike prior episodic censorship efforts, the Complete Library campaign institutionalised systematic, idea-based censorship, with ambiguous enforcement creating an atmosphere of fear and self-censorship.

This censorship practice shares notable parallels with censorship and policy implementation in contemporary China and other contexts. First, delegation played a key role: local officials – many of them motivated by career incentives – were tasked with confiscating banned books. Second, ambiguity was central to the process: vague guidelines created uncertainty while reporting mechanisms encouraged mistrust and fear. Finally, probabilistic but severe punishments amplified the chilling effects. While most banned books did not result in individual punishments, the cases of punishment enforcement were exceedingly harsh, including the execution of authors, publishers, and their family members. Together, these characteristics suggest significant chilling effects on knowledge production.

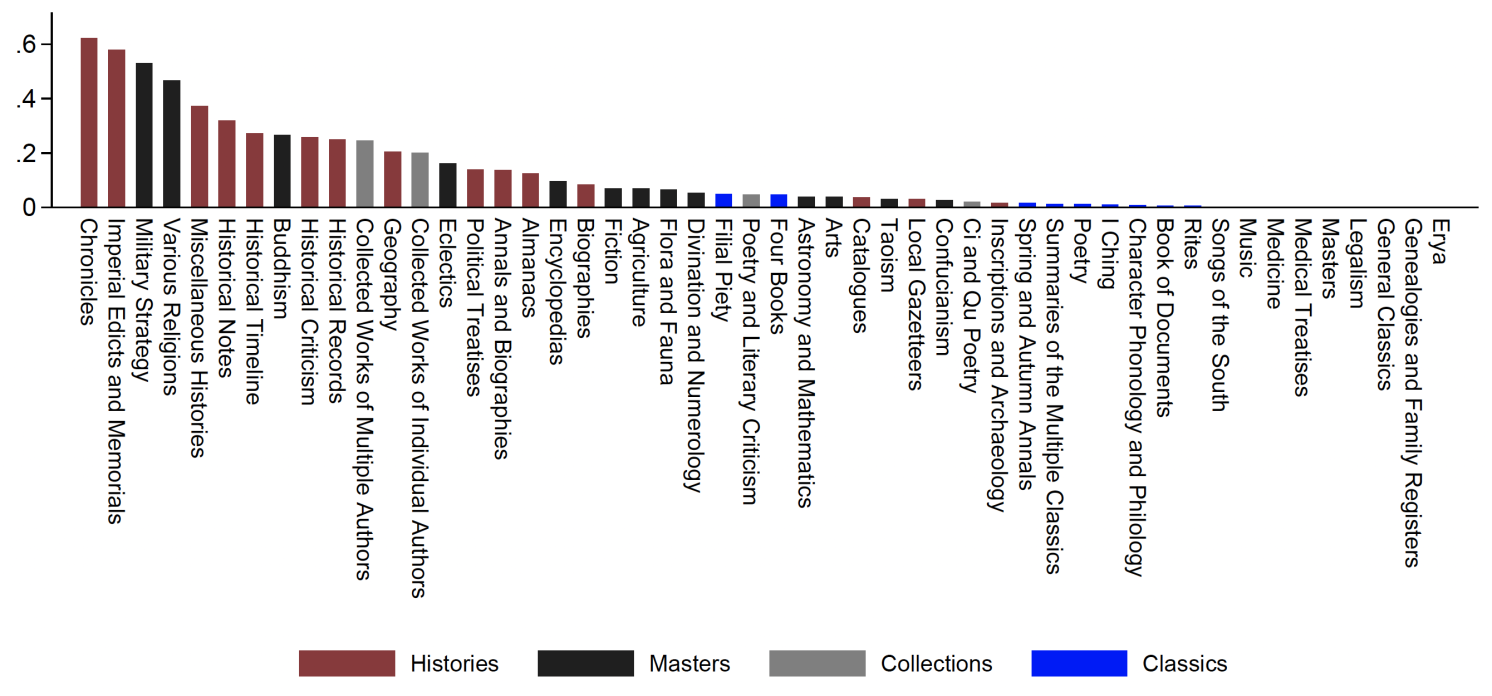

In Bai et al. (2024), we compile a comprehensive dataset of book publications drawn from the General Catalog of Pre-modern Chinese Books, which includes detailed information on publication years, authors, and publishers. We integrate records of banned books from official archives and historians’ research, leveraging the long-standing classification system that divided books into four sections (hence the name Complete Library in Four Sections) and 50 categories. To measure censorship, we calculate the share of banned books within each of the 50 categories relative to the total number of collected books (see category-level censorship in Figure 1). Employing a difference-in-differences approach, we analyse publication patterns and book content before, during, and after the Complete Library campaign, with yearly data between 1662 and 1949.

Figure 1 Censorship degree by categories

Note: Figure plots the level of censorship across 50 categories. For each category, the level is measured by the share of banned books among total collected books.

Suppression and Resilience in Knowledge Production

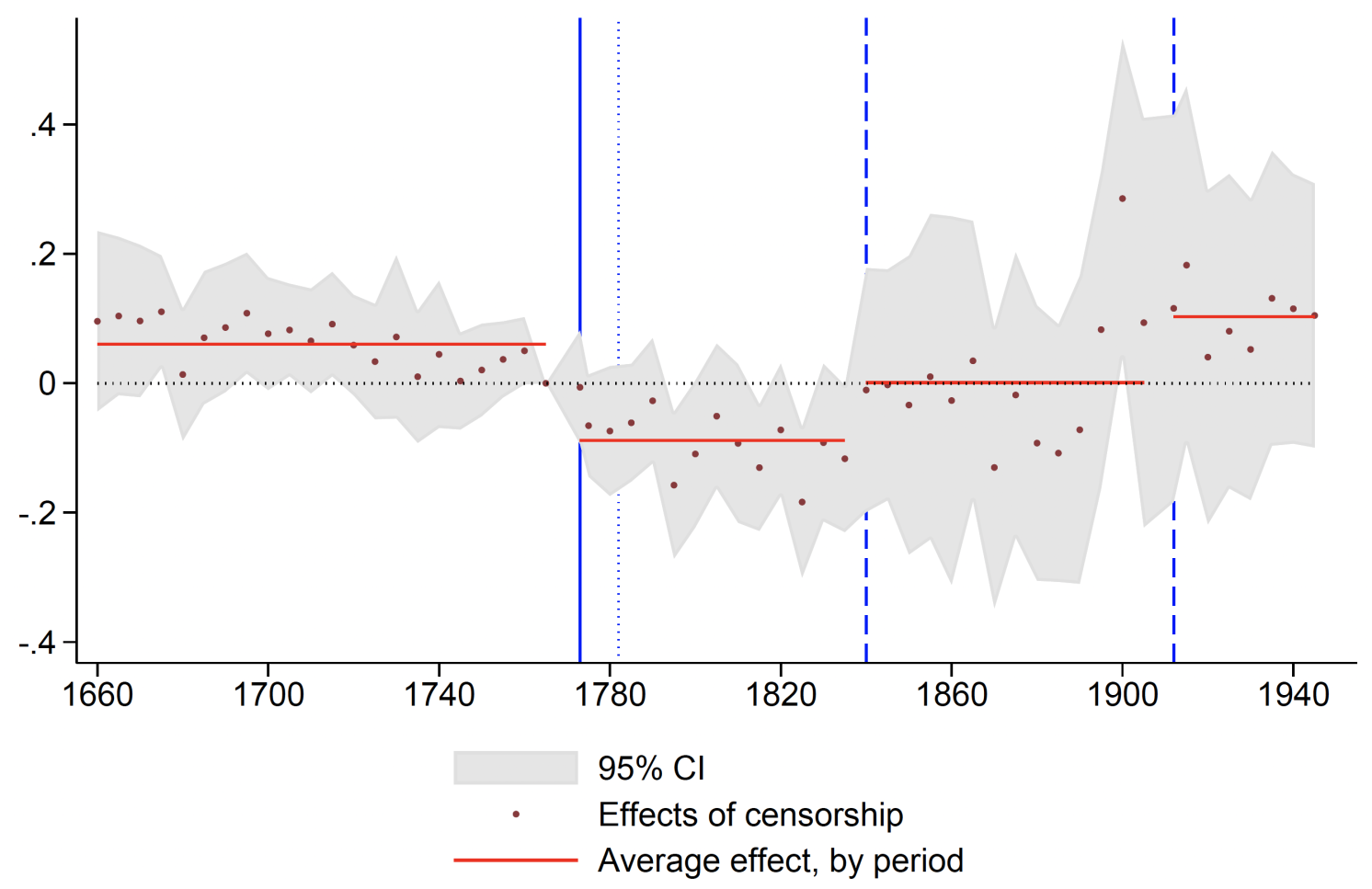

Figure 2 presents the event-study estimates on the impact of censorship, highlighting both suppression and resilience. From the 1770s to the 1830s, categories subjected to higher levels of censorship experienced a significant decline in publications, with a one standard deviation increase in censorship associated with an 18% reduction in book production.

However, the 1840s marked a turning point. Political upheavals, including the Opium Wars and the subsequent Taiping Rebellion, significantly weakened state control. We observe a resurgence in book production within previously censored categories followed, likely reflecting the diminished state control over society. We also find that the revival began earlier in treaty ports (which were forced to open) and their neighbouring regions compared to inland China.

Figure 2 Impact of censorship on books logged

Note: Figure plots the estimates of the effect of censorship on book publication every five years, using 1765–1772 as the reference period.

Book Contents and Chilling Effects

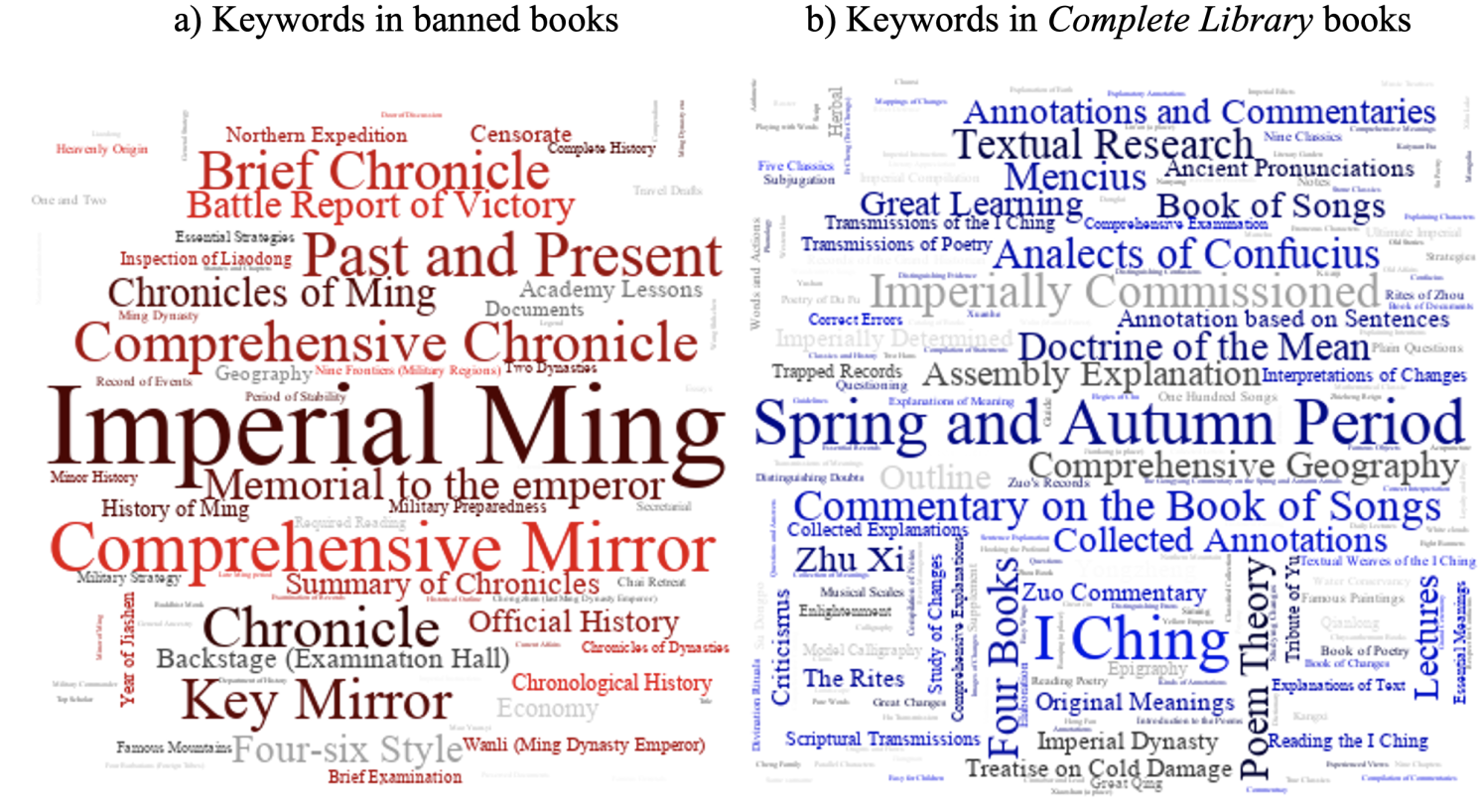

To explore how censorship influences book content, we analyse keywords in book titles. Figure 3 displays keywords from banned books alongside those from the Complete Library collection. The analysis reveals that the number of unique keywords within a category followed a pattern similar to the decline and revival observed in the number of book titles, indicating that these dynamics affected not only publication volumes but also the diversity of ideas.

By measuring a book title’s similarity to the two sets of keywords, we construct a proxy for the sensitivity of a book’s topic. Our findings indicate that both sensitive and less-sensitive books within restrictive categories experienced a decline and subsequent revival. However, since less-sensitive books constituted the majority of publications, chilling effects played a critical role in shaping the overall dynamics. Furthermore, the suppression and revival patterns extended to new keywords, highlighting the chilling effects on the generation of new ideas during the suppression period.

Figure 3 Keywords in banned books and Complete Library full-text books

Note: Left panel displays keywords found in banned books; right panel displays keywords from the Complete Library full-text books. Font size indicates word frequency. Red colours indicate words used in the section ‘histories’; blue colours indicate words used in the section ‘classics’.

Responses from Publishers and Authors in the Decline and Revival

By examining publishers and authors active across different periods, our research reveals that both groups adapted to censorship. Specifically, authors who died before 1772 (and could not respond to censorship), with books in more censored categories were less likely to be published during 1773–1839, reflecting publishers’ adjustments to censorship. Similarly, for publishers active after the 1840s (i.e. after the suppression effect dissipated), authors alive during the period 1773–1839 were less likely to have work in more restrictive categories, indicating authors’ adaptive responses.

Notably, the decline and revival in book publications can be attributed largely to the exit and entry of publishers. During the 1770s–1830s, publishers were more likely to exit from highly restricted categories. However, after the 1840s, new publishers began entering the market, revitalising previously suppressed fields. Using a Bartik-style instrument – which predicts the number of publishers in a category based on aggregate changes and the initial distribution of publishers across categories – our study confirms that these publisher dynamics can explain the observed decline and revival in book production.

Implications

Despite seven decades of suppression following a systematic censorship of ideas, this study reveals a remarkable revival in knowledge production following the loosening of state control. This finding both complements and diverges from the existing literature, which highlights the long-term detrimental effects of censorship through channels such as social and human capital (Xue 2021, Drelichman et al. 2021, Dewitte et al. 2024). While these channels may have been active during the suppression decades, our study suggests that publishers, authors, and readers adapt their behaviours in response to significant shifts in the political climate. This aligns with the broader notion that environmental changes play a critical role in shaping the balance between persistence and change (Giuliano and Nunn 2021).

While this resurgence is notable, it does not diminish the significant negative effects of censorship. From the 1770s to the 1830s – a period often characterised as one of intellectual stagnation – China experienced significant population growth but saw limited innovation and cultural development. This intellectual stagnation contrasts sharply with the contemporaneous flourishing of progressive ideas and technological advancements in Europe during the Industrial Revolution (Mokyr 2016, Almelhem et al. 2023). The suppression of knowledge in China during this critical period may have had important political and economic consequences, hindering the country’s ability to adapt to and engage with the transformative global changes of the era.

Furthermore, the importance of publishers in driving these patterns is noteworthy. It suggests the influence of intermediaries – such as publishers – in implementing and responding to censorship. This insight is still relevant in the digital age, when platforms and intermediaries continue to shape the flow of information and knowledge production.

Censorship has left a lasting imprint on languages and publishing practices around the world. This column analyses the impact of state censorship on knowledge production during the largest book-banning campaign in Chinese history, from 1772 to 1783. Categories subjected to stricter censorship – including history, conflicts, and religious studies – saw significant declines in publication following the bans, but political upheavals and the erosion of state control after 1840 triggered a resurgence. Publishers played a crucial role in both the suppression and subsequent revival of knowledge production.

Originally published at VoxEU

I’m old enough to remember the last days of book censorship in Ireland – my older siblings had their little stashes of banned books which I eagerly sought out (usually to be very disappointed). If anything, it usually proved good publicity for writers like John McGahern or Edna O’Brien. Although in the case of the former, he lost his teaching job after his first book was banned – in reality, its the ‘other’ forms of pressure which hit banned authors more than a simple book ban.

The issue for China is that historically bans are more effective as there were few opportunities for alternative sources unless the curious reader wants to travel. Most Chinese communities around the world now have some very interesting bookshops (the first one I encountered was in a tiny room upstairs from a restaurant and internet cafe in a side street in Dublin) which take advantage of the relative freedoms, although many Chinese will tell you that they are often run by government agents – they are a handy way to keep track of dissidents. But the inventiveness of Chinese netizens in getting around censorship can lead to a lot of fun and interesting memes and a whole new form of creativity (Winnie the Pooh being the most famous).

The key problem of course with censorship is that it slows down the spread of ideas. Regional economists and geographers have various measures that are used to compare the spread of ideas and innovations, and China tends to rate quite low in these (although in truth I’m very dubious about whether these indices really mean a lot). But there is little doubt but that in Imperial days in China the heavy censorship did seriously constrain the economy.

“Poem Theory”. No kidding. Not going to find that in the American version of that word salad. We get “Extra Ranch”.

Rather than ancient Chinese censorship, it would be more interesting to seeing how it is done these days. Like silent agreements not to allow books by certain authors like Thomas Frank to be published at home. Or to allow books to only have one run at being published with no supporting pr campaign and then letting it sink into obscurity. Or going through libraries to remove controversial books like those by Mark Twain who everybody knows was a damn commie. And those are only physical books but it is far worse for digital books where they can be more easily rewritten to modern audience’s tastes, their wholesale deletion, etc. With the internet I thought that it would be possible to have every book ever written be available online. Instead the opposite is happening.

Yes, that perplexes me as well. In addition to separation of church and state, separation of corporation and state, separation of profit and truth/academia/science, it seems we also need a separation of state and profit from the internet.

the polar opposite of censorship and prohibition — promotion, publicity, and prescription — must also have profound effects that may fade quickly from one era to another. Mark Twain was part of the American secondary school canon, but is he now? Think of the Bible, Shakespeare, or the Song of Hiawatha.

As the U.S. economy has evolved the media conglomerate, the ability of centralized bureaucracy to control and coordinate the production and distribution of books, movies, television has escalated. The critic or reviewer is an employee of the same conglomerate as the distributor or the producer. Amazon makes movies, publishes reviews, distributes the “content” etc.

What is being promoted as orthodox dogma is a critical context for censorship effects alongside the institutional and technical means for promotion. Control is promotion and prohibition, propaganda and censorship. And centralization of both is a factor in cultural flowering or stagnation, I would think.

For further reading, A Universal History of the Destruction of Books is quite good and among other episodes, it does discuss the massive destruction from around 200 BCE mentioned above. It’s available for free here at the archive with an account. Or order at your local bookstore!

“Most Chinese communities around the world now have some very interesting bookshops…which take advantage of the relative freedoms, although many Chinese will tell you that they are often run by government agents – they are a handy way to keep track of dissidents…”

Chinese government agents (Chinese Communist agents) are busily recording my movements about the libraries and bookstores they run, especially about the licentious children’s sections meant to entice me to Hans Christian Andersen.

https://english.news.cn/20240423/4b925af4e0174184befb6ee86ba0f4b6/c.html

April 23, 2024

Rural library opens new vistas for villagers in southwest China canyon

By Lu Yifan and Xiong Xuan’ang

KUNMING — Gan Wenyong’s first-ever exposure to extracurricular reading occurred at the age of nine, when he encountered the book “The Little Prince” by French author Antoine de Saint-Exupery.

The experience served as a motivation for Gan to step out of the mountains and explore a different world. Also inspired by the book, he returned to his hometown in southwest China’s Yunnan Province over a decade later and built a rural library to nurture the dreams of the local children.

“Books lighted my way forward, and I think children in the mountains need the same passion to explore the world,” he said.

Gan, 29, is the founder of the library called “Banshan Huayu” (half hill flower talks) and a legal aid services provider. He was born and raised in Qiunatong, a village nestled at the northernmost tip of the Nujiang River canyon in the province’s Gongshan Dulong and Nu Autonomous County.

Qiunatong was once entrenched in absolute poverty. Due to the financial difficulties of his family, Gan missed out on educational opportunities in his early years. Instead, he spent his childhood collecting herbs, fetching water from mountains, and tending to livestock.

“I didn’t have shoes until I was six years old,” he recalled, adding that back then, there was no electricity in the village, and candles were used to illuminate his home after sunset…

On the film front, the Chinese govt only permits the public exhibition of the latest American blockbusters. Older American films (Citizen Kane, Treasure of Sierra Madre, etc.) and US independent movies cannot be screened.

I don’t know enough about Chinese book printing at the time–when they certainly had moveable metal type–but the story makes an interesting contrast with Europe, where the book trade benefited enormously from the multiplicity of different cities and principalities, each with their own laws. And whilst the Church could wield the Index as a weapon against its believers, it required the local authorities to pass laws enforcing it, which not all did. As a result, books that were banned in one area, for political or religious reasons, were quickly republished elsewhere, and there was a brisk trade in books printed in Germany or the Netherlands, with fake title pages, and smuggled into Catholic countries. It seems likely that anyone sufficiently determined could probably get hold of books that were on the Index more or less anywhere. (And ironically, the Index itself became something of a best-seller because it amounted to a very profitable list of books for Protestant printers to publish, with the equivalent of “Banned by the Catholic Church” on the front page.)

So I doubt if the same problems really affected Europe, although there were certain countries (Spain is an example) where the sheer difficulty of access made getting hold of banned books problematic, and where intellectual life suffered as a result. Later, of course, books were censored on moral grounds–notoriously you could buy Joyce’s Ulysses in Paris, and many visitors did–and there were still books in my childhood that had to be smuggled in from abroad.

But these days we have copyright protection, and this means that the old habit of printing banned books elsewhere is much more difficult. On the other hand, I wonder whether unexpurgated versions of Enid Blyton books will someday be smuggled across the border from the US into Canada?

Jared Diamondmade the same points about China many years ago as a side to either Collapse or Guns, Germs, and Steel, don’t remember exactly.

https://www.litcharts.com/lit/guns-germs-and-steel/chapter-16-how-china-became-chinese

1997

Guns, Germs, and Steel

By Jared Diamond

Summary

China is often considered one of the most politically, culturally, and linguistically monolithic countries in the world. Since 221 B.C., China has been united under one government. Also, the vast majority of Chinese people speak Mandarin, and most of those who do not speak one of a relatively small number of other languages (6 or 7) that are closely related to Mandarin. But how, exactly, did China become “Chinese”—or rather, how did China stay Chinese for so many centuries?

Analysis

In this chapter, Diamond will apply the theory of geographic determinism to Chinese history in an attempt to explain one of the biggest anomalies in history—how China has remained so linguistically, culturally, and politically similar over the course of the last 2,000 years (while so many other countries have gone through revolutions and paradigm shifts in the same amount of time).

“I don’t know enough about Chinese book printing at the time…”

Interesting thoughts on intellectual diversity in Europe.

There was a time in Tasmania, long, long, ago, when “My Autobiography” by A. Trollope was banned…

Famously, the South African apartheid government banned “Black Beauty”, as well as “The Joy of Sex”.

Nowadays there is no need for such bans, as hardly anybody can read for coherence and if they can, they can’t afford to buy books.