Yves here. Perhaps this is old hat to readers, but it was news to me that globalization, in particular offshoring, had largely stalled out after the 2008 financial crisis. The authors focus on the role of uncertainty. I would hazard another factor played a role, which was US pressure to get China to increase the value of the renminbi. Geithner repeatedly threatened to designate China a currency manipulator, which would have had significant consequences. In the Obama first term, the case that the renminbi was too cheap was colorable. However, China engineered a slow appreciation but accusations that the renminbi was artificially low persisted after China had very quietly relented. So I wonder how much China being less obviously a bargain played into offshoring decisions.

The article usefully describes that reshoring tends to happen only when automation, as in robotics, is high.

By Marius Faber, Senior Economist Swiss National Bank (SNB), Gleb Kozliakov, Dalia Marin, Senior Research Fellow Bruegel; Professor of International Economics Technical University Of Munich. Originally published at VoxEU

After a long period of rapid globalisation, the openness of the world economy has stagnated since 2008, largely owing to a halt in intermediate goods trade between developed and developing countries. This column argues that increased uncertainty, coupled with ever more capable automation technologies, has likely contributed to this trend break.

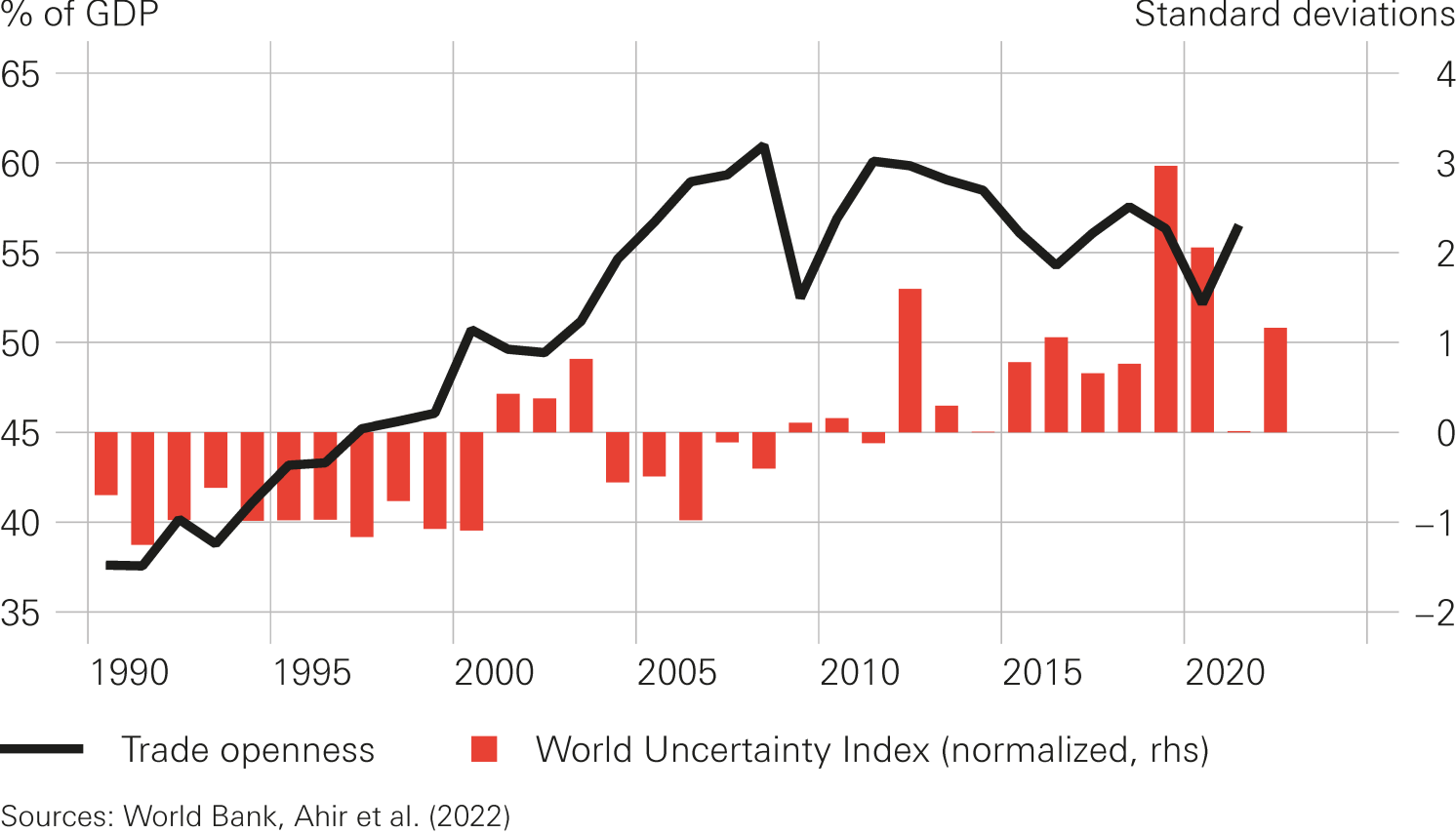

Globalisation has come to a halt since the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008 (Figure 1, black line). Trade as a share of GDP rose by more than one percentage point per year in the period of hyper-globalisation between 1990 and 2008, but has since entered a period of stagnation. This slowdown can, in large part, be attributed to a halt in the growth of intermediate goods trade between the developed and developing world. Between 2000 and 2007, the share of total inputs sourced from developing countries has almost tripled, corresponding to an average annual growth rate of about 15%. But with the GFC, this rapid expansion ended abruptly, followed by a period of decline.

Figure 1 Trade openness and World Uncertainty Index since 1990

Sources: World Bank; Ahir et al. (2022).

Notes: Trade openness is measured as the sum of exports and imports as a share of GDP. The World Uncertainty Index (WUI) is computed by counting the share of words that are either “uncertain” or a variant of it in the Economist Intelligence Unit country reports.

While many factors may have been at play (Baldwin 2022), two major developments have likely contributed to the declining globalisation since the GFC.

First, economic uncertainty shocks have become larger and more frequent, partly owing to stronger international trade linkages. Examples are the European debt crisis from 2011 to 2014, Brexit in 2016, the US-China trade war since 2018, and the Covid-19 crisis starting in 2020 (Figure 1, red bars). After experiencing the risks associated with high exposure to trade, firms may have started to reconsider their relationships.

Second, automation technologies have made substantial advances and can now perform a range of tasks that were previously offshored. Moreover, in their effort to fight low inflation, central banks have ensured extraordinarily favourable financing conditions after the GFC, effectively lowering the cost of capital relative to labour (Marin and Kilic 2020). This has made it especially attractive for firms to invest in ever more capable, domestically installed automation technologies rather than employing foreign labour as a means of production.

While it seems plausible to assume that uncertainty and automation reduce globalisation, their impacts are, in fact, theoretically ambiguous. Regarding uncertainty, the direction of the effect depends partly on whether firms view the domestic or the foreign economy as more prone to shocks (Grossman et al. 2023). Regarding automation, the direction of the effect depends largely on the relative strength of the (negative) displacement and the (positive) productivity effect (Acemoglu and Restrepo 2020, Artuç et al. 2023).

Empirical Strategy

Because of this theoretical ambiguity, in a recent paper (Faber et al. 2024) we empirically estimate the effect of uncertainty on reshoring – and the role played by automation in facilitating it. We consider 18 developed countries, 17 developing countries, and 19 industries in the period between 2000 and 2014. In our empirical strategy, we exploit the fact that country-industry pairs were differentially exposed to uncertainty shocks in the developing world between 2000 and 2014 because of their pre-existing trade relationships in 2000. 1 We argue that our (shift-share) measure of exposure to developing countries’ uncertainty induces plausibly exogenous variation in uncertainty as (1) uncertainty shocks in developing countries are unlikely to be caused by reshoring decisions in the developed world; and (2) it is based on pre-determined country-industry-level trade patterns, alleviating concerns related to simultaneity. To explore the role played by automation, we ask whether this relationship differs by the degree to which tasks in each industry are replaceable by industrial robots. 2

Main Results

Higher uncertainty leads to more reshoring, but only in highly robotised industries. Our results show that higher uncertainty in developing countries increases the relative use of domestic inputs, but only in highly robotised industries. This suggests that reshoring in response to uncertainty in developing countries seems to become economically feasible if tasks can be performed (at relatively low cost) by a domestically installed robot. Our point estimate implies that an uncertainty shock of one standard deviation in connected developing countries increases the relative use of domestic inputs by about 7%.

Firms appear to move production in-house, rather than rely more on domestic suppliers. Next, we want to know whether our measure of reshoring (domestic inputs/imported inputs from developing countries) increases as a result of more domestic inputs, fewer imported inputs, or both. Results show that the reshoring response to an uncertainty shock comes entirely from fewer imported inputs from the developing world and not from more domestic inputs. This suggests that firms reorganise and move input production in-house, instead of relying on other domestic input suppliers when faced with higher uncertainty. One possible reason for this reshoring response is that firms want more control in uncertain times. Another is that it is costly to find new suppliers if firms need to invest in a supplier relationship, and moving production in-house may be the less costly alternative (Antràs and Helpman 2008).

The reshoring response triples after the GFC. To examine whether reshoring occurred in particular after the GFC, we rerun our preferred specification but split the sample into two subperiods: the pre-GFC and post-GFC periods. Results show that the reshoring response to uncertainty more than triples after the GFC. Possible reasons are higher risk aversion following the traumatic experience after the GFC, advances in automation making robots more efficient, and the low interest rate environment making investment in robots more attractive relative to hiring workers.

Reshoring response is not driven by single countries or industries. Next, we want to examine whether our results are dominated by a single hub of global values chains (GVCs) like the US or Germany. Our results do not change when we individually exclude each high-income country or each industry. Moreover, the results do not appear to be solely driven by the automobile sector as has been often argued (Freund 2022).

Higher uncertainty does not lead to more diversification. In theory, it may be optimal for firms to respond to higher uncertainty also by diversification, i.e. to import inputs from a larger set of locations, to ensure that supplies are still available even if one location is shocked. To test for this possibility, we construct a Hirsch-Herfindahl measure of foreign supplier concentration. Results show, however, no significant impact of developing countries’ uncertainty on diversification, suggesting again that the cost of finding new suppliers may be quite high.

Major Threats to Identification

Our results are robust to several threats to identification, including reverse causality and the most important ones arising from shift-share instruments. We address concerns about reverse causality first. Reshoring by developed countries may affect uncertainty in developing countries rather than the other way around. We use two alternative identification strategies to tackle this concern. First, in a ‘narrative approach’, we use only locally generated spikes in uncertainty, for which the narrative for why the spikes happened suggests that the event was plausibly exogenous to reshoring decisions in developed countries. We then use only uncertainty changes for which we have identified a plausibly exogenous spike in uncertainty and set all other changes to zero when constructing the exposure to uncertainty in developing countries variable. Our estimates remain virtually unchanged, suggesting that our results are not biased by reverse causality.

Second, in a ‘small open economy approach’, we exclude the five largest developed country destinations for developing countries’ inputs (the US, Germany, South Korea, France, Italy). These account for almost 70% of all imported inputs from developing countries. The idea is that small developed countries have a lower potential to cause substantial uncertainty in developing countries than large ones. We then rerun our preferred specification with data excluding these large developed countries. Reassuringly, results remain unchanged. Overall, this reinforces our view that our results are unlikely to be driven by reverse causality.

Finally, we test for threats to identification in shift-share designs. Following Borusyak and Hull (2023) and Adão et al. (2019), we show that our uncertainty shocks are as good as randomly assigned and not driven by noise.

Conclusion

Our research shows that the slowdown in globalisation has been intensified by uncertainty shocks, on the one hand, and the option to automate production on the other. Cost savings from offshoring to low-wage countries have become smaller as various uncertainty shocks have increased the risk of default of input delivery. Sectors able to substitute the tasks of developing countries by domestic robots reshore production to their home countries. Reshoring in-house rather than to domestic input suppliers in other industries appears to dominate among the different reshoring strategies. Having control appears to becomes more valuable when firms realise that the world has become an ever-riskier place. An important implication of our results is that major forces weighing on globalisation had already started well before the re-election of Donald Trump, suggesting that the slowdown of globalisation is not simply due to recent geopolitical events.

Authors’ note: The views, opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this column are strictly those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Swiss National Bank (SNB). The SNB takes no responsibility for any errors or omissions in, or for the correctness of, the information contained in this column.

See original post for references