By Jonas Jessen, Postdoctoral Researcher at German Institute for Employment Research (IAB), Robin Jessen, head of the research group “Microstructure of Taxes and Transfers” and researcher at the Department of Macroeconomics and Public Finance at RWI – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research in Berlin, Andrew C. Johnston, Associate Professor of Economics at the University of California, Merced and a Faculty Research Fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and Ewa Gałecka-Burdziak, Associate Professor at SGH Warsaw School of Economics. Originally published at VoxEU.

As governments worldwide grapple with labour shortages and systemic budget shortfalls, the question arises of how unemployment insurance policies potentially contribute to this imbalance by increasing and extending nonemployment. This column argues that recent debates around unemployment insurance reform, which often focus on the effect among job seekers, overlook potential unintended consequences among the employed. Taking moral hazard among employed workers into account has substantial effects on the welfare implications of unemployment insurance.

Traditional analyses of unemployment insurance (UI) systems examine how benefit generosity affects job search behaviour and unemployment duration. Recent research by Bell et al. (2024) and Landais (2015), for example, demonstrates that more generous benefits lead to longer unemployment spells. However, these studies capture only part of the story by focusing on the unemployed alone.

Our research (Jessen et al. 2025) reveals a previously underexplored dimension: UI generosity also significantly influences currently employed workers’ behaviour. Using unique policy discontinuities in Poland’s unemployment insurance system, we find that higher UI benefits not only extend unemployment spells but can actually increase transitions into unemployment, particularly when benefits are both generous and long-lasting.

The Natural Experiment: Poland

Poland’s UI system provides an ideal setting to study these effects through two distinct policy features:

- Potential benefit duration: Claimants receive 12 months of benefits instead of six if local unemployment exceeds a certain threshold (Jessen et al. 2023)

- Benefit level: Workers receive 25% higher monthly benefits after reaching five years of covered employment

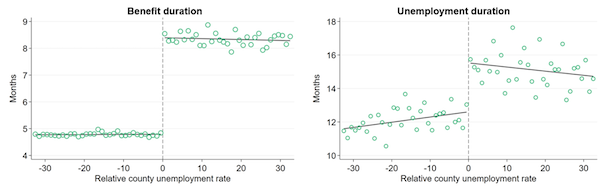

These clear cut-offs create natural comparison groups on either side of each cut-off, allowing us to measure how UI generosity affects outcomes for both employed and unemployed workers. Figure 1 illustrates the potential benefit duration (PBD) variation by plotting average benefit and unemployment duration around the threshold where the potential benefit duration increases by six months.

Figure 1 Benefit and unemployment duration around the PBD threshold

Notes: Figures show months in benefit receipt an in unemployment in bins of percentage point of county’s relative employment rate.

Key Findings

Leveraging the policy variations in the Polish UI system, we find that increasing benefit levels or benefit durations by 10% both lead to a 3% increase in unemployment duration. As extending benefit durations has a larger impact on total benefits paid, this comes with a higher direct cost for taxpayers.

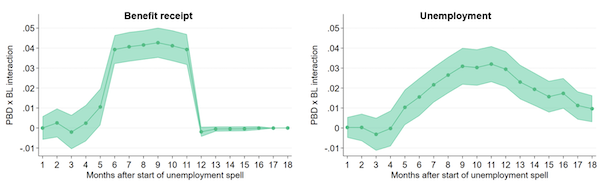

As the variation in benefit levels and benefit duration is independent, the setting allows us to provide novel insights into how the two key parameters of UI generosity interact. In a two-way regression discontinuity design, we find that the effect of benefit level increases is substantially larger when the benefit duration is also extended. In Figure 2, we present monthly estimates of the level-duration interaction, showing that this amplifying effect materialises after benefits expire under the less generous regime (the coverage effect; see Bell et al. 2024). The positive interaction suggests that the moral hazard costs of increasing benefit levels are substantially amplified when workers have access to longer benefit durations.

Figure 2 Monthly estimation of the benefit-duration-level-interaction term of two-way regression discontinuity estimates

Note: Figure shows monthly RD estimates of the interaction term of PBD extensions and benefit level (BL) increases. Shaded areas indicate 85% confidence intervals.

We also study whether a more generous UI can improve workers’ long-term prospects by improving job match quality as documented by Kugler et al. (2021) and Weber and Nekoei (2015). Tracking workers over five years after their initial unemployment spell we find no evidence that workers benefit from more stable job matches as we find no decreased unemployment probability over the five-year horizon.

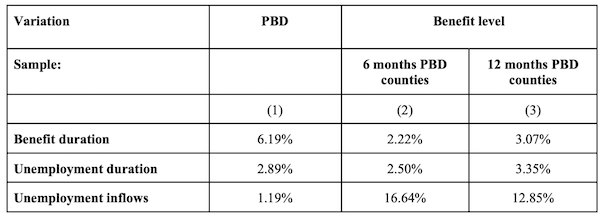

We move on to examine whether unemployment insurance creates moral hazard among employed workers by increasing transitions into unemployment. A 10% increase in potential benefit duration leads to a modest increase of 1.2% in unemployment inflow. Yet, strikingly, a 10% increase in benefit level generates a substantially larger increase in unemployment inflows of 13-17%.

A summary of the effects of increases in benefit levels and durations is presented in Table 1. The large difference in inflow effects suggests that increasing benefit levels generates larger distortions among the employed.

Table 1 Effects of a 10% increase in UI generosity

Policy Implications

Policy Implications

Our findings have profound implications for UI policy design. The traditional focus on balancing consumption smoothing against job search incentives misses a crucial aspect: the effect on employed workers’ behaviour. Our welfare analysis suggests that accounting for this ‘employed worker moral hazard’ dramatically changes the cost-benefit calculation of UI policies.

For instance, in the standard model that only considers unemployed workers’ behaviour, the cost of transferring $1 to the unemployed through higher benefits is about $2.3 in behavioural distortions. However, when we extend the canonical models for welfare analysis to include the effect on employed workers, this cost rises to over $10, primarily due to increased transitions into unemployment. For benefit extensions the behavioural distortions increase from $2.5 to $3.6.

This does not mean UI benefits should be eliminated – they play a crucial role in providing economic security and enabling effective job search. However, policymakers should consider (1) reducing the benefit level while increasing benefit durations, as they create fewer distortions and provide more value to those truly in need; and (2) experimenting with insurance programmes that mitigate moral hazard by either paying claims as a lump sum or using unemployment insurance savings accounts that reward workers when they avoid unemployment (Feldstein and Altman 2007).

Looking Forward

As workforces age and budget liabilities come due, understanding these complex policy interactions becomes increasingly important. Our findings suggest that optimal UI policy requires a more comprehensive approach than previously thought. While providing adequate support for the unemployed remains valuable, policymakers must also consider how benefit structures affect social welfare by their effects on employment and output, which shapes overall welfare.

I don’t get it. What’s the link between employee moral hazard and unemployment? Do Polish workers just choose to get unemployed? In the U.S., people don’t typically choose to quit and then draw unemployment benefits.

Even if there is more agency where workers can facilitate their own unemployment and get benefits, how is this a fair welfare model? Did they consider whether such workers have more bargaining power and hence get higher wages? The text implies that the authors only checked whether workers with higher benefits have higher unemployment odds over 5 years, not whether they have higher wages or better working conditions: “Tracking workers over five years after their initial unemployment spell we find no evidence that workers benefit from more stable job matches as we find no decreased unemployment probability over the five-year horizon.”

Does the actual paper address cohort issues? If benefits are higher in areas with more unemployment, surely that means you’ll see a correlation between benefit level and workers entering unemployment–the economy there is worse?

Thank you. So tired of these articles that make it sound like people enjoy being lazy and shiftless so they can collect freebies. I don’t know how the Polish system works, but as you alluded to, in the US you can’t quit and draw unemployment at all – you have to have been laid off. My laid off friends and I used to call these “benefits” unenjoyment because there was nothing fun about being broke.

When I collected benefits after being laid off years ago, the benefits were not the entirety of your regular wage, and if you worked at all while collecting benefits, you were required to report the part time, non permanent work so they could reduce the already paltry amount they doled out. I’d been working part time under the table at a 2nd job when I was laid off from the first, and my employer knew it. I needed both the UI and the part time wages so I didn’t lose my apartment, so I didn’t report the work. For some reason the state dept. of labor questioned my benefits and I had to have a sitdown with the state rep and my former employer to see if I would need to reimburse them for the benefits that had long been spent. Luckily my former employer lied for me and didn’t tell them I had an under the table job.

If these types are so concerned with “moral hazard” from those collecting UI, maybe instead of giving workers the shaft, they could discourage mass layoffs by employers every few years who mismanage their businesses.

@lyman alpha bob — Re: “moral hazard”: but that would be very different world, wouldn’t it?

Their “moral hazard” ain’t ours, right?

A nice piece of work.

Re ‘moral hazard’, the MMT perspective is that it is preferable for the state to provide a job than to enable soul-destroying exclusion from the workforce. And, of course, funding does not come from the taxpayer it comes from the state.

While almost entirely contrarian, MMT is never more so than in stating the state can provide useful employment – that there is nothing ‘superior’ in private employment vs public. Indeed, it argues a moral hazard in monopoly private employment suppressing wages and degrading working conditions – the gig economy – and that private employment that cannot provide a living wage, including benefits, should be eliminated by a state-run job guarantee.

It takes us down a path of wondering why working hours are so long, what happened to leisure and what is ‘work’ anyway – a word whose precise meaning is thermodynamic that we borrowed from steam engines.

And, of course, what ‘GDP’ – a measure of extraction and ruthless blindness to so-called ‘externalities’ has to do with anything relating human, social, environmental or planetary health and why we have to monetize everything in the first place.

Just saying, when it comes to moral hazard let’s not stop at the employed worker looking over her shoulder for a ‘free’ lunch.

Hmmm. I know not enough of Poland to speak specifically, but from thirty thousand feet I’m not seeing a discussion of the potential influence from;

Long Covid/ADD, (I can’t focus on detail work anymore)

Multi front existential crisis, ( what me worry?)

Tail effect of transitioning to the digital age, (My skill set is no longer relevant/I don’t “speak the new language” well enough to get a job worth taking)

Immigrants, (surely they have an effect)

“Hustle economy”, (ditto)

It reads as if there are abundant jobs with good pay that leave your dignity attached. I’m having a hard time believing.

>>It reads as if there are abundant jobs with good pay that leave your dignity attached.

Thank you, mrsyk. With respect to dignity, I would add that the unemployment claim process which I am familiar with, unfortunately, here in one of the bluest of blue states, is designed to make one feel like a criminal in every step of the process from the initial filing and continuing through the submission of each weekly claim. One is faced with bold, glaring words warning of dire consequences if one’s claim isn’t “valid.” It’s a soul-destroying process, and leaves one with no dignity whatsoever.

Good morning j, I too have been down that road a couple times with similar takeaways (giveaways?).

Solidarity, mrsyk.

Solidarity j indeed. It will give me a reason to smile as I’m shuffled off my mortal coil.

If they did what some researchers do (Came up with a theory and then went to look for data which would confirm or reject their theory) then maybe it would have been good if they for clarity stated their theory.

As is, I do not see much widespread, if any, moral hazard proven.

Possibly due to my personal experience: I’ve come across very few people who voluntarily left salaried employment to go into unemployment. My experience is that people rather stay in a bad job while looking for something better rather than quitting outright and becoming unemployed.

Some/many/most(?) unemployment insurance do not pay out for some time if the claimant voluntarily left paid employment.

The hidden cost of accepting the wrong employment is huge and they want to make it even bigger. A company who hires the wrong employee does have some costs but the costs for the employee (an actual human being) is higher due to damage done to career.

Some careers can never recover and if the price to pay for rooting out bad employers is adequate UI then a people oriented policy would ensure that the UI is adequate.

To me the report looks like ‘modern research’: Put in lots of data into a data analysis tool, press a button enough times to torture the data to get pleasing graphs and write a report likely to please the ones paying for the research being done….

What next? Show that full employment is possible if and only if we allow wages go to zero?

…increasing benefit levels or benefit durations by 10% both lead to a 3% increase in unemployment duration.

Why would increasing benifit durations by 10% only give a 3% increase in unemployment duration. Intuitively the argument breaks down here.

I wonder what a 3% increase in unemployment duration is? Are we looking at 3 days or 3 months. It would be interesting to see that data set.

Your second point is EXTREMELY important for a study like this.

An increase in benefit duration of 10% will of course depend on the starting duration. If the initial duration was 10 weeks, then a 10% increase would be an extension of paid benefits (UI) to 11 weeks. This is set by the government. An individual on unemployment takes this as a given duration during which they can collect benefits. They most often will not be able to change this. Filing the initial claim is not necessarily a humane process, as mrsk and judy2shoes attest.

This is an informative link for the US: https://www.cbpp.org/research/economy/how-many-weeks-of-unemployment-compensation-are-available

For the US, a 10% increase in the duration in many states would be an increase from 26 weeks to 28.6 weeks or roughly 28 weeks and 4 days. This varies by state.

The unemployment duration is the length of time that a person does not have a job, but is looking for one. A person (in theory) has more control over the unemployment duration. This can end one of three ways: Our unemployed job seeker accepts an offer and starts work, ending the duration of unemployment. Second, our job seeker can get discouraged and drops out of the labor force, thus technically also ending the ‘duration’ of unemployment. Third, our unemployed job seeker still has no job and is looking for one as the time limit expires. In this case, the duration of benefits collects just ends, which affects the measurements – is this person still looking for work and not receiving benefits, and importantly, how do we know?

As previous commenters noted, there are many effects that seem not to be considered here – the strength of the regional economy, the assumed welfare bonus preference of private over government or public employment, the whole construct (GDP, etc.), cohort effects, bargaining power . . .

It would also need to consider whether the government has capped total duration for a lifetime.

I hope this helps.

Back in the day it was called “collecting.” It was a loop-hold that was worked by many unskilled, working-class women. My mom was a regular user when New England still had textile mills. She would work for six months and then contrive to get herself laid-off. She would then “collect” for six or so months until her eligibility ran out. Then it was back to work in another mill until her eligibility kicked back in again. Normal behavior in my neighborhood.

Ahh. It seems as if some workers have figured out how to structure their own PTO benefits.

Your mother would have been a good fit for my industry. As long as I’ve been in it (25 years), busy season is July through mid-November, with a small burst of activity right before the New Year for clients to justify their budgets. The challenge was always how to incentivize the skilled “unskilled” workers to stay with the company during the off season, since said workers aren’t going to stick around if they’re only given 15 hours a week come February. The traditional solution was to site facilities way out in the country where land was cheap and the same people would come back every autumn to run the equipment after the harvest. For many different reasons that became a less and less viable solution so now we rely on “technology” to fill the gaps.

Hey Chuck Roast. Here in fly-over country corporations figured out how to exploit the US system long ago. They would hire “seasonal employees” for the busy season, and then lay them off 2 or 3 days before they would qualify for Unemployment.

This was rampant in canning companies, work ’em 80 hours a week, then lay them off before they would qualify for benefits. It also happened a lot in warehousing and retail work.

Hello Old…another demonstration of how the economic stability of working people has diminished over these years. Geez, even the textile barons weren’t that cruel…eventually. The old man drove a truck under a union contract. Real stable for a working guy. It seemed that my mom worked to supply the surplus. They died comfortably and without a care.

Now in fly-over you’re getting the new, way-post Flint predacious financial and monopoly capitalism that rules with it’s usual tender mercies on the locals. They can organize.

OK…. worried about moral hazard ? Let’s eliminate UI benefits entirely …. that’ll set us on the straight and narrow….. Wondering why this piece was profiled, unless of course as an example of Naked Capitailsm….

You claim the article is “an example of Naked Capitalism” which indicates you are familiar with the site. But if you were, you would know we often run articles that we and the readership don’t agree with in order to familiarize ourselves with other points of view and to critique them as the commenters have done. Critical thinking is the goal of the site, apply some here. Also, your comment borders on an attack on the site which is not allowed. Criticize us in a respectful manner but keep the sarcasm to yourself. And yes, that’s a warning.

Understood …. I value the NC site…. SL

I think that semper loquitur took umbridge too quickly. When I read Sig Lasers comment. I took it that was an kind of sharp play on words. As in capitalism laid bare i.e. naked capitalism.

The article overlooks the systemic nature of unemployment. If I throw nine bones out my back door and release ten dogs to retrieve a bone, it doesn’t matter how well-educated or skillful dog #10 is, he won’t get a bone.

Fiddling around the edges with training, job placement, etc. ignores the fundamental design of the system which is to supply too few jobs.

Have a job guarantee, and that goes away. It also supplies workers with automatic “f**k you money” … an alternative to an abusive employer.

But employer abuse–AKA “labor discipline”–is the point of the current system.

The article seems to assume that receiving UI benefits is a smooth process. Here in the US, I became underemployed early last summer. After months of wrangling with the Dept. of Labor I FINALLY received the princely sum of 2000$ about a month ago. If it weren’t for my partner and a high-interest credit card, I would have become homeless. Here, if you quit a job you aren’t eligible for UI anyway so the “moral hazard” is inapplicable.

In construction, 4.8% of the U.S. economy, https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/employment-by-major-industry-sector.htm, the day you walk onto a job you begin working your way out of a job. Contractors use unemployment as a means of keeping the labor pool ready to go. Unions often cover the dehumanizing aspects of the unemployment process which helps, but you sorta get used to being laid off every so often.

Back in the day, in Atlantic Canada, fishermen (obviously seasonal), would receive full unemployment benefits until the next fishing season, despite the fact that they had each earned more than most Canadians during the fishing season (say six months-ish?) and had not been subsequently employed for a certain contiguous period of time (as required in the rest of the country, at least one fulll year) rquired for full benefits. Understandable, somewhat, as a sop to a perceived disadvantaged (justified or cynically a vote buying opportunity) part of the country. This also extended to industries in the same region(s) of the country. Taxpayers of the entire country subsidizing the smaller demographic of those working for less time (and benefit compensation than would otherwise) risked the obscene profits of the local politically contributive concerned corporations.

Disgracefully, and obviously, poitically beneficicial rules for the benefit of certain constituents over others is hardly democratic, regardless of the proffered excuses of the current corporate-owned state media.

Cheers.

C_T

So they thought it was timely to do this study now?

I’d say it depends on the intention of the ones paying for the study and doing the study:

If their intention with this study was to kick on the unemployed then I am convinced they believe it is always a good time to kick the unemployed.

If their intention was something else like improving equality or improving the quality of life for people then I suppose that the timing was especially bad.