Yves here. This post is a more extensive assessment of the topic broached by KLG via e-mail and that I hoisted into a post. KLG described how proposed indirect overhead cuts for NIH and NSF grants would put most large med school research into a loss. Rajiv Sethi goes much further in documenting the damage, that it would put the universities themselves in a loss and have a devastating impact on advanced research across a very broad front. This would rapidly undermine the US’ contested leading position, above all compared to China, when Trump has made containing China a top priority.

Sethi also describes how J.D. Vance earlier and in very blunt terms described universities as the enemy and how they needed to be brought under the control of conservatives. Recall how we have repeatedly described the massive growth in student debt as a PMC growth and enrichment project, particularly with the great increase in the relative size of well-paid, “doing exactly what?” administrators. One of the big project, despite the very large increase in Federal funding via loans, was enlarging fundraising staff. Yet one of the notable results was how much of the new money went into glitzy, not-education-value added initiatives like new buildings and fancy gyms. Those edifices create naming opportunities.

By Rajiv Sethi, Professor of Economics, Barnard College, Columbia University &; External Professor, Santa Fe Institute. Originally published at his site

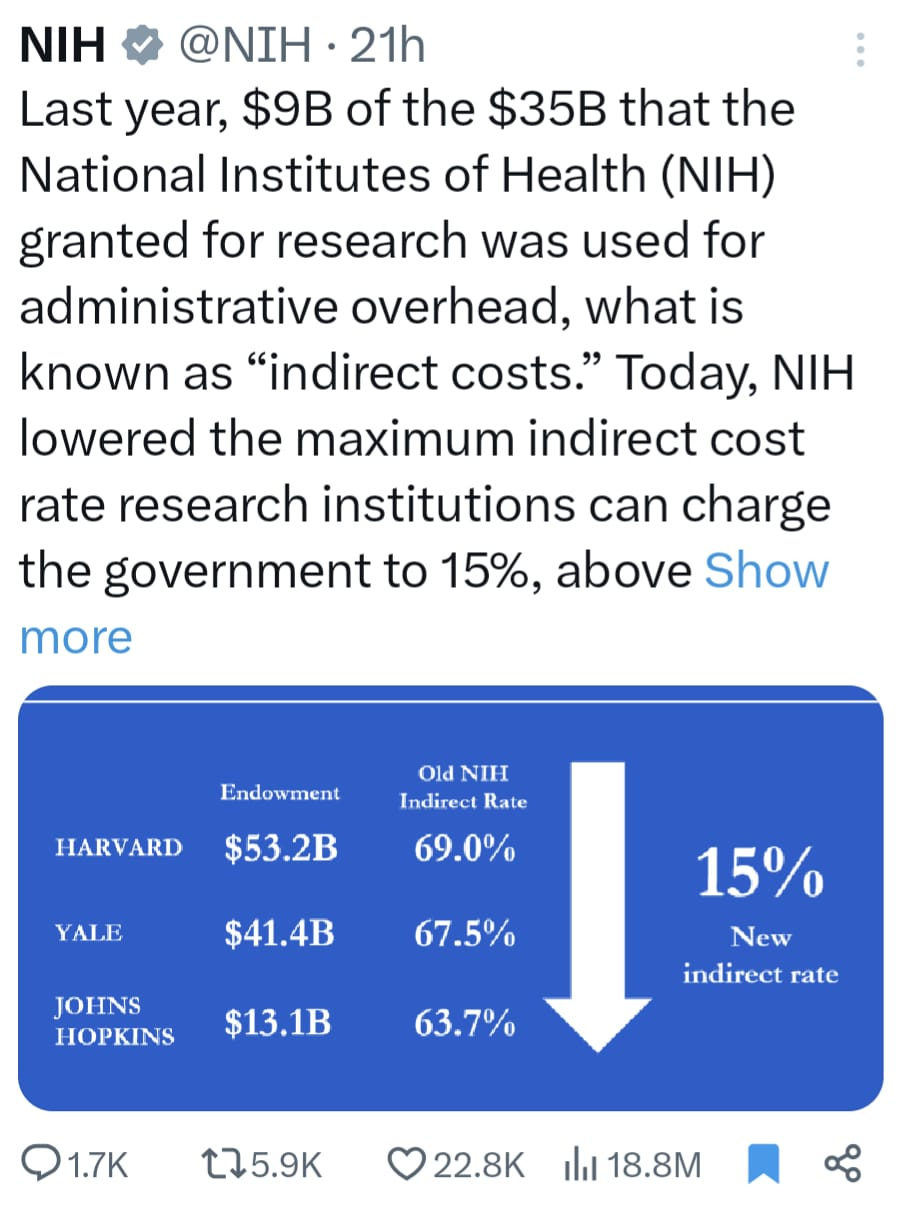

Late last week, the National Institutes of Health announced a major reduction in the maximum allowable rate at which universities and research labs are compensated for facilities and administrative costs associated with federal grants:1

A federal judge has temporarily blocked this change from taking effect in 22 states following a challenge by a coalition of attorneys general. Pennsylvania is not among the states that sued, and Penn State has paused both the submission of new applications to the agency and the acceptance of new awards that carry the reduced indirect cost rate. I suspect that many major research universities have made or are contemplating similar pauses, not wanting to commit themselves to the lower rate until the dust has settled.

I don’t know how these legal battles are going to play out, but if the cap on indirect costs is sustained, it will have profound effects on balance sheets. Columbia, for example, is expected to lose over 100 million dollars a year from this one change alone, and twice as much if other federal agencies follow suit. Stanford’s projected losses are in the same ball park. Other major research universities, including flagship state schools, all face roughly the same fate.

The last time there was a fiscal shock of comparable magnitude was during the pandemic, when Columbia faced about 300 million dollars in net losses over two years due to reduced occupancy in housing units, a precipitous drop in the number of international students, lower revenues from medical procedures, and new expenditures on testing, tracing, student evacuation, and upgraded classroom technologies. The university responded with employee furloughs, hiring and salary freezes, temporary reductions in retirement benefits, depletion of cash reserves, and new debt issuance.

The difference this time is that the fiscal shortfall is of indefinite duration, and cannot be addressed by temporary measures. Harvard’s president has argued that the proposed cap “would slash funding and cut research activity at Harvard and nearly every research university in our nation.” He predicts the following consequences:

The discovery of new treatments would slow, opportunities to train the next generation of scientific leaders would shrink, and our nation’s science and engineering prowess would be severely compromised. At a time of rapid strides in quantum computing, artificial intelligence, brain science, biological imaging, and regenerative biology, and when other nations are expanding their investment in science, America should not drop knowingly and willingly from her lead position on the endless frontier.

For reasons discussed below, such arguments are unlikely to sway those responsible for higher education policy in the current administration.

It is possible that the courts will block changes to the terms of awards that have already been issued. Perhaps they will even prevent changes in the rates attached to awards made in the current fiscal year, given that these were negotiated and agreed upon several months ago. But I don’t see what prevents the administration from simply refusing to agree to rates above the proposed cap when negotiations for the next fiscal year commence.

That is, had the administration simply announced that future negotiations would be subject to the reduced cap, I don’t think that grant recipients would have had a case for legal action.

So why not simply do this instead of changing rates midstream?

My guess is that the primary goal was not the anticipated budgetary savings, which (over a long horizon) would have been roughly the same with delayed implementation. The goal—as was the case with public tariff announcements against Colombia and our major trading partners, the abrupt curtailment of foreign aid, the intention to acquireGreenland and the Panama Canal, and the proposal to forcibly resettle the entire population of Gaza—was to project immense power and the willingness to use it.

It’s important to understand that the NIH announcement is just the opening salvo in an all-out assault on universities that has yet to begin in earnest. Other initiatives currently being contemplated include the leveraging of the accreditation process to force major changes to the curriculum, the filing of federal civil rights cases, and the taxation and partial confiscation of endowments. We may also see selective denials of visas for foreign students and the targeted freezing of federal grants and contracts.

The sitting Vice President has described American universities as the enemy. To get a clear sense of what he means by this, consider the following remarks made about an hour into a podcast episode recorded in 2021 (emphasis added):2

Universities I really believe are the gatekeepers. Everything runs through the universities… Everything that is broken about our society—from Fauci’s authority to the things that our kids are being taught in the sixth grade—runs through the university system. There is no way for a conservative to accomplish our vision of society unless we’re willing to strike at the heart of the beast. That’s the universities.

So the idea that we get a little bit more diversity at Harvard or Yale or Ohio State, or we maybe make things a little bit nicer for conservatives, or we found some conservative clubs on campus, no no no no no. Unless we’re willing to de-institutionalize the left in those institutions—or destroy the institutions absent that—we are going to continue to make the most powerful academic actors in our society actively aligned against us. The only way to work is to actually take some of these institutions over.

Back in 1918, the British politician Eric Geddes argued that on the matter of war reparations, Germany should be “squeezed as a lemon is squeezed—until the pips squeak. My only doubt is not whether we can squeeze hard enough, but whether there is enough juice.”3 University endowments in the aggregate currently hold more than 800 billion dollars in total wealth. There are about thirty institutions (including virtually all Ivy Plus schools and a number of flagship state universities) with more than five billion each, and another hundred or so with more than one billion. That’s a lot of juice, and the temptation to “take it over” is accordingly immense.

The endgame here seems to be the installation of loyalists on boards of trustees and in senior administrative positions. Universities will resist this loss of autonomy, and may prevail in the end, but they will pay a very steep price along the way.

The country, too, will pay a price.

You can’t bludgeon an institution (or nation) without strategic adjustments being set in motion. In response to the tariff threats—even those that were withdrawn in the face of concessions—I have argued that there will be long term changes in global trade flows and geopolitical alignments. What might be the long term effects of the squeezing of American universities?

I can imagine two kinds of adjustments—the movement of people across institutions, and the movement of institutions across borders.

Nils Gilman predicted back in July of last year that actions such as those currently being taken would “spell the end of the post-WWII global hegemony of American academia.”4 Consider, for instance, the winners of Nobel prizes in Physics, Chemistry, and Medicine over the past five years. Of the 37 total recipients, 22 were affiliated with American institutions at the time of the award. Eight of these these were born elsewhere—in Britain, France, Germany, Hungary, Japan, Lebanon, Russia, and Tunisia.

Nobel prizes typically recognize research done decades in the past. The international presence in American higher education is even more pronounced today than it was then, and encompasses a broader range of source countries. These people have crossed oceans to study and work in American labs. They do so because that is what others like them are also doing—they jointly create the environment within which they feel they can thrive. It’s a positive feedback loop that has entrenched America’s position at the cutting edge of multiple research frontiers.

But it is in the nature of positive feedback loops that they can also operate in reverse. Too tight a squeeze of higher education runs the risk of turning a virtuous cycle into a vicious one. Other countries may see an opportunity to attract the scientists who are currently drawn to American universities. For example, the University of Toronto, Monash, Seoul National, and the Max Planck Institutes are already major centers for research, and with the support of their respective governments, could anchor the growth of new scientific ecosystems.

But there’s another possibility worth considering. The leading American universities are globally recognizable brands. They can leverage their reputations by setting up satellite campuses in far-flung locations, as New York University has already done. Potential hosts would compete to offer inducements in the form of research infrastructure and intellectual autonomy. Squeezed at home but embraced abroad, these institutions would be in a stronger position to weather the storm. But some of the local economic spillovers they generate for domestic companies and communities would be lost.

American universities are certainly not beyond reproach. I have argued repeatedly that they are in serious need of reform. Confidence in them has declined sharply over the past few years, especially but not exclusively among Republicans. They need to acknowledge that there are legitimate reasons for this, and work to regain the public trust. This requires embracing institutional neutrality, protecting free expression even when allegedly harmful, and building a climate in which self-censorship is not incentivized. It also requires adopting admissions practices that are transparent and defensible in plain language, and systematically tracking the lifelong achievements of graduates so that they can test and improve their selection procedures in ways that are mission-aligned. These are all changes that are desirable in their own right, regardless of political pressures or threats faced.

But whatever their flaws, American universities are also powerful magnets for global talent and major export engines on which our economy depends. Squeezing them hard may provide their fiercest critics with some short-run satisfaction, but like the cottager in Aesop’s fable, we may end up losing a steady stream of golden eggs.

Anyone who was surprised by NIH announcement really hasn’t been paying attention. Just three weeks after the election last year, Vivek Ramaswamy declared an intention to do exactly this, arguing that it would be “a great early win” for Jay Bhattacharya at the head of the agency and that the Department of Government Efficiency would “gladly help him deliver it.” Ramaswamy has since parted ways with DOGE but he was just a mouthpiece for the policy, not it’s originator.

In transcribing JD Vance’s spoken words I have dropped fillers such as like and you know. The recording was made a few months before he ran in a contested Senate primary in Ohio, a race he managed to win thanks in large part to an endorsement by Donald Trump. It’s safe to say that his transition from “skeptic to superfan” was already close to complete by the time of the podcast interview.

The memorable phrase coined by Geddes was repurposed by Denis Healey in 1974, when (as Chancellor of the Exchequer) he pledged to “squeeze property speculators until the pips squeak.” A decade later Healey ran for the Labour Party leadership and lost to Michael Foot; the history of Britain would have been quite different if he had prevailed.

Gilman seems to have deleted his account on X, and with it his remarkably prescient thread.