Yves here. Admittedly, this post is meant to be read by academic economists, but it’s so understated as to the grim state of German manufacturing as to have a “The war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage” quality to it. The headline depiction of Germany’s manufacturing woes as mere “recent weakness” belies the fact that the severity of much of the damage has a “bleeding out” quality to it. The factors that the article blandly lists, such as the impact of higher energy prices and sorry state of the automobile industry ex China, aren’t adequately translated into effects now underway and what they mean. Factory closures, or even overly-long shuttering of production lines, resulting in lasting and potentially irreversible damage. Skilled workers and managers move on, often to roles that don’t require the expertise they accumulated in a factory setting. This is how a mere downturn slowly morphs into deindustrialization.

By Marco Flaccadoro, Economist Bank of Italy. Originally published at VoxEU

Germany’s manufacturing sector has struggled since 2021 due to rising energy costs, weak global demand, and a declining automotive industry. This column describes how higher gas consumption in energy-intensive industries, trade fragmentation, and competition from China have hit Germany harder than other euro area economies, and shows that shocks in German industry significantly impact neighbouring countries. With energy prices high and demand subdued, challenges for Germany’s manufacturing sector – and its European partners – are set to persist.

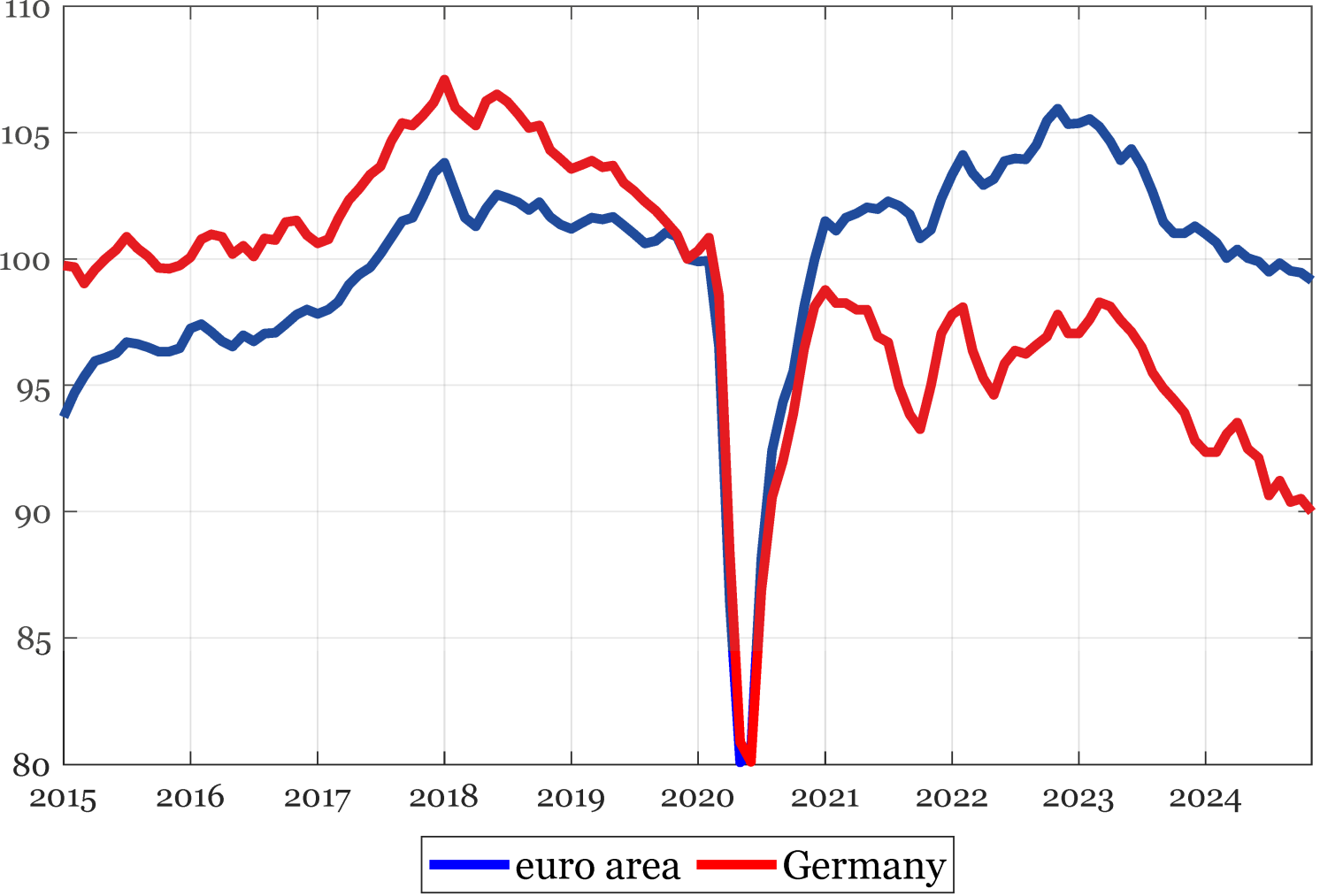

The surge in energy prices, which started at the end of 2021, has severely impacted the euro area manufacturing sector, the output of which has declined below its pre-pandemic level in late 2024 (Figure 1). German industry was strongly affected (Bachmann et al. 2022) and experienced an even steeper contraction, reducing its output by approximately 10 percentage points. The weakness of the industrial sector in Germany is a reason for concern for the whole euro area: given the tight integration of manufacturing activity across euro area economies (Amador et al. 2015), developments in the German industry may generate significant externalities.

Figure 1 Manufacturing production indices (2019Q4=100)

Source: Eurostat and author’s calculations.

Note: all data are seasonally adjusted and in 3-term moving averages. Last observation: November 2024.

In a new paper (Flaccadoro 2024), 1 we shed light on three main factors that contributed to Germany’s relatively weaker performance in the past few years, and analyse the spillover effects to other euro area economies.

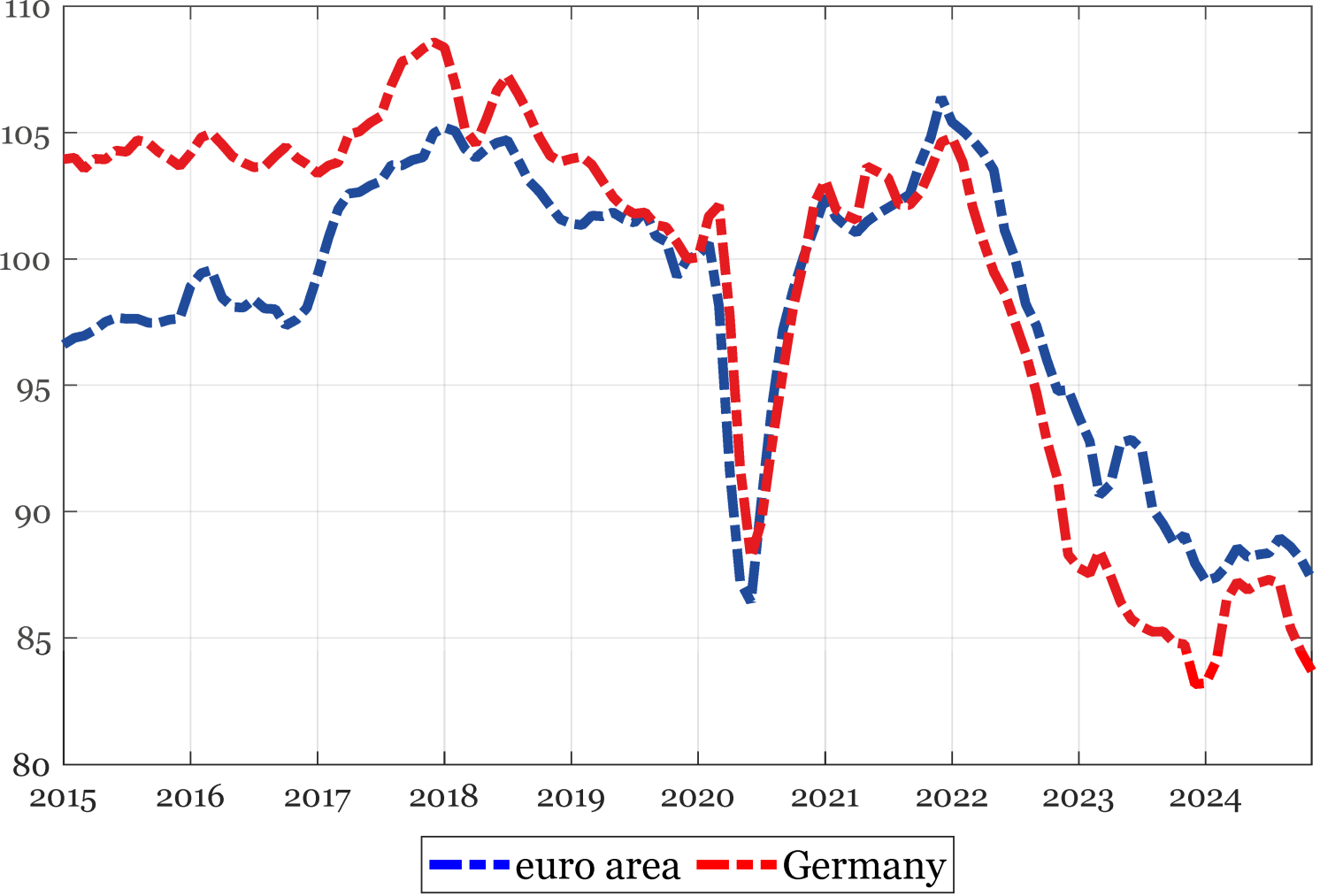

The Energy Crisis

First, the rise in energy costs in Europe affected manufacturers more severely in Germany than it did in other euro area countries. Energy-intensive industries – i.e. those displaying a relatively high natural gas content in their production process 2 – account for a similar share of manufacturing in Germany and in the euro area overall. Likewise, there were no significant differences in gas prices between Germany and the euro area when looking at non-household heavy energy users over the past few years. Thus, it is plausibly the higher intensity of gas consumption in Germany’s gas-intensive industries that disrupted production there more than in other euro area countries, particularly in the chemical sector. Indeed, the chemical sector in Germany is more reliant on natural gas as an intermediate input than in other euro area countries because of its technological characteristics. Due to the chemical industry’s significant connections with other sectors, its weakness passed through to other energy-intensive industries, causing a more pronounced decline in production within German energy-intensive sectors compared to the euro area as a whole (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Production in energy-intensive sectors (2019Q4=100)

Source: Eurostat and author’s calculations.

Note: the industrial production index relating to the energy-intensive industries is computed using the following sectors (NACE 2-digit classification): C17, manufacture of paper and paper products; C20, manufacture of chemical and chemical products; C23, manufacture of other non-metallic mineral products; and C24, manufacture of basic metals. All data are seasonally adjusted and in 3-term moving averages. Last observation: November 2024.

Weak Demand Conditions

Second, the slowdown in global demand for goods, rising trade fragmentation, and intensified competition from Chinese producers have impacted German manufacturing firms more than those in other major euro-area countries, due to Germany’s greater trade openness. In fact, in 2023 goods exports accounted for 34% of GDP in Germany, against 27% in Italy and 23% in France. Furthermore, Germany’s goods exports were more tilted towards China (6.1% of total goods exports, compared to 4.2% in France and 3.1% in Italy). 3 In addition, price competitiveness indicators computed by the Bank of Italy (Felettigh and Giordano 2018) show a deterioration for German manufacturers since mid-2022 with respect to other euro area countries, associated with the increase in energy costs and, later, the faster wage dynamics. This dynamic stood in contrast to the significant competitiveness gains achieved by German firms in the early 2000s following the Hartz labour market reforms (Fadinger et al. 2023).

Consistently, German exports of goods have lost momentum: after increasing in the aftermath of the pandemic crisis, they declined below pre-pandemic values in the summer months of 2024 (Figure 3). In contrast, euro area exports increased by approximately 5% above their pre-crisis levels in the same period.

Figure 3 Exports of goods (2019Q4=100)

Source: Eurostat, and author’s calculations.

Note: chain-linked values; last observations: 2024Q3.

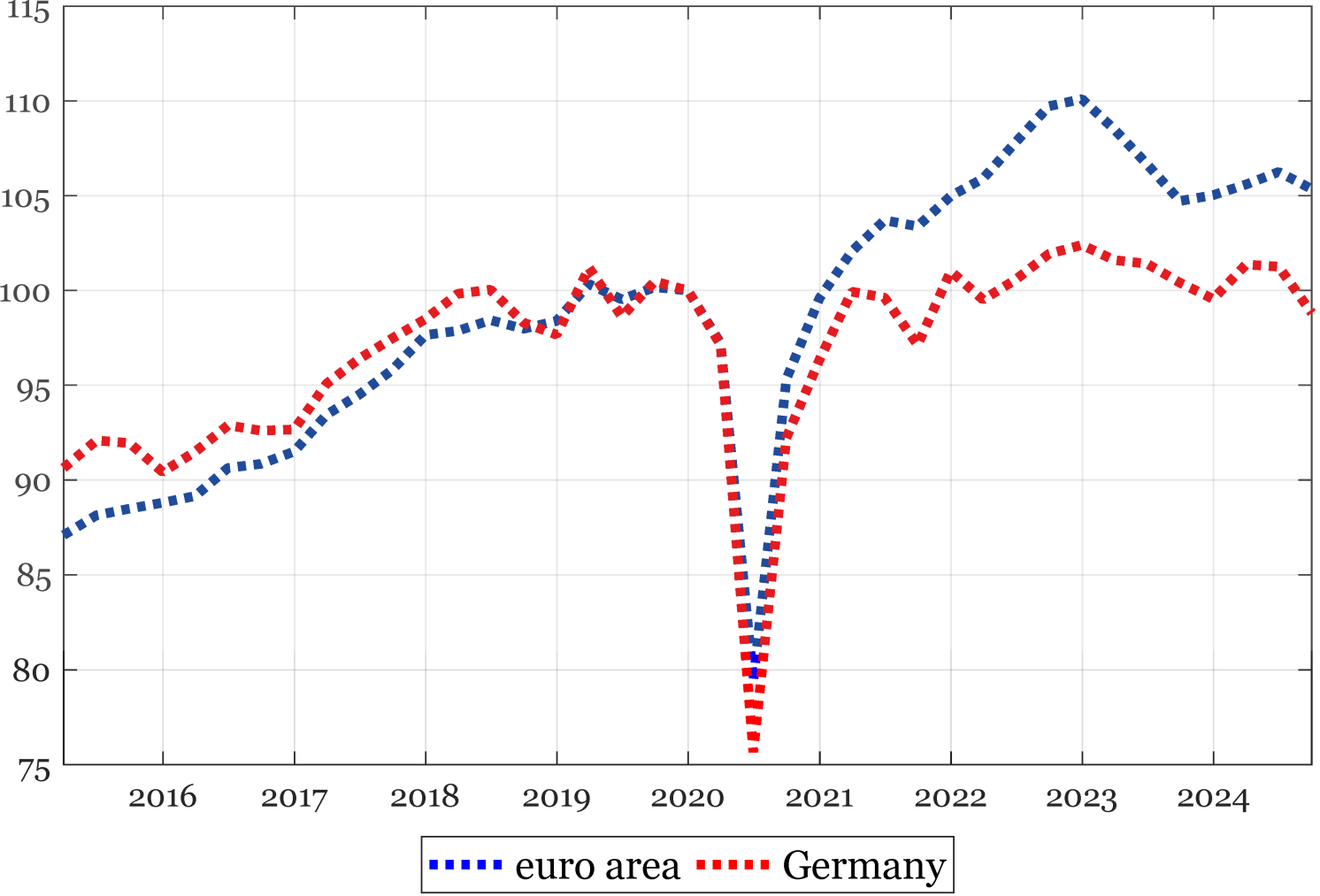

Decline in the Automotive Industry

The third factor is the downturn in the automotive industry, the weight of which is twice as relevant in Germany than in the euro area as a whole. This sector is affected by low demand and increasing competition from Chinese carmakers. Accordingly, quantitative demand-side indicators for the motor vehicle sector are consistent with lacklustre domestic demand for cars, as shown by the downward trend in car registrations in the euro area as a whole (Figure 4). Al-Haschimi et al. (2024) show that between 2019 and 2023, the euro area car industry faced adverse developments in its relative producer prices and a reduction in market shares with respect to Chinese manufacturers. 4 In particular, China is a fierce competitor for European car manufactures, as its low-cost electric vehicles (EVs) are exported to Europe in large numbers. Given that the EU represents the most important market for the exports of German EVs (85% of exports, almost $20 billion), China represents a critical source of competitions for German carmakers.

Figure 4 Car registrations (2019Q4 = 100)

Source: Eurostat and author’s elaborations.

Note: All data are seasonally adjusted and in 3-term moving averages. Last observation: December 2024.

Finally, recent developments in the regulatory framework have sparked further uncertainty for car producers, both in Germany and in the EU. First, duties on the imports of electric vehicles from China, imposed by the European Commission in October 2024, could possibly induce some retaliation, dampening European car exports. Second, the potential re-opening of the 2035 zero emissions target for new cars and vans, which was adopted by the European Commission in March 2023 within the ‘Fit for 55’ deal, may induce EU households to postpone spending.

Spillover Analysis

We now present the results of a spillover analysis that allows us to quantify the interdependence of manufacturing activity across the main euro area economies. In particular, we follow the approach of Diebold and Yilmaz (2009) and measure spillovers via the variance decomposition associated with a vector autoregressive (VAR) model. According to this approach, we estimate the spillovers from country i to country j as the fraction of the forecast error variance decomposition at a six-month horizon in country j due to shocks originated in country i. Our baseline estimates focus on the period January 2010 to December 2019, to avoid our results being affected by the global financial crisis and the pandemic-related disruption to economic activity, and use data referring to the manufacturing production index of nine economies (Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Finland, and Portugal). Our findings are robust to extending the period of analysis up to July 2024, or backward to January 2000, and to controlling for industrial developments in the US and China. The spillovers from the German industry to the manufacturing sector of other euro area economies are large. In fact, the shocks originated in the German industrial sector explain almost 31% of the forecast error variance of the Italian manufacturing activity six months later; while, shocks originated in the Italian manufacturing sector explain roughly 11% of the variability in German industrial activity. Spillover effects from Germany are also sizable for France and Spain; while the innovations originating in these two countries determine more attenuated spillovers in the German manufacturing sector.

Looking Ahead

The challenges presented above are not likely to dissipate soon. First, EU gas prices are set to remain above pre-energy crisis levels in the years to come. Second, the outlook for demand remains subdued and geopolitical factors pose a downward risk for economic activity. Third, demand is particularly weak for firms in the automotive sector, whereby the competition from Chinese manufacturers is set to intensify in coming years, especially in the green energy technology segment.

Author’s note: The opinions expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Bank of Italy.

See original post for references

Wanna know the most amazing thing about this article? It talks about Germany’s energy problems and all the rest of it but not once did he mention the root cause of Germany’s energy problems – the blowing up of the NS2 gas pipelines and the series of sanctions that Germany has levied against their major energy provider. If some of Germany’s industries relied a lot on gas that was OK as Germany had access to cheap, reliable gas coming direct from a country to the east whose name we will not mention. So going by this article, three years after the war began, it is still not permitted to mention any of this in what is supposed to be a scientific study. That dog is still not barking.

I am a bit puzzled by that article where energy issues are discussed while ignoring the role that infrastructure plays in them. Energy production and distribution requires an extensive infrastructure which, in the course of decades, gets built and optimized for specific configurations of customers, applications, and geography.

When Germany decided to do without the gas from Russia, it immediately faced a deficit that had to be compensated. Since supplies from the North Sea could not be increased rapidly, the government expedited the installation of FSRUs (Floating Storage and Regasification Units) — specialized ships, docked on a long jetty, that can pump LNG from LNG carriers, turn it into gas, and inject it into a pipeline leading from the jetty to the onshore network. In 2024, there were about 8 of such FSRU active in 5 German harbours.

The problem with FSRU: this is indeed the fastest way to set up a LNG terminal, but it is the most expensive one to operate — 40% more than a land-based terminal; and LNG is already more expensive than pipeline gas. This is acceptable as a short-term, emergency fix, but not as a long-term solution.

The resulting gas prices were sufficiently dissuasive that some terminals are under-utilized, and that DET (the Deutsche Energy Terminals GmbH) that charters many of those FSRU, has been accused by other private operators of underpricing its services — leading a private operator to exit the German market for FSRU services.

The alternative would be to direct the LNG carriers to (cheaper) land-based terminals in neighbouring countries, have the LNG regasified there, and then transported via the European network of onshore pipelines to Germany. Spain and France are the European countries with the most land-based LNG terminals and the greatest capacity to handle such flows.

There are two main usages for natural gas. Household consumption as in heating buildings and cooking. Industrial usages as raw material in chemical processes. For safety reasons, the odourless natural gas intended for households must be “odorized”. But the substances used to that effect are definitely unwanted in the gas intended for industrial applications.

The problem: in Germany, industries and cities gew close together and are spread in the interior of the country, especially in the Ruhr. The injection of odorants takes place as late as possible, at the local level when the retail network branches towards industrial and residential areas via low-pressure pipework. The high-pressure “backbone” network carries unadulterated gas. In France, this is exactly the reverse: injection of odorants takes place as early as possible — because industries relying upon gas are generally located on the coast, close to the LNG terminals and the end of offshore pipelines from Algeria. Thus, the French high-pressure network carries “odorized” gas towards the interior of the country.

It is of course technically possible to “deodorize” the gas coming via the French network; it is just that the resulting gas becomes, again, significantly more expensive.

The article states:

“Thus, it is plausibly the higher intensity of gas consumption in Germany’s gas-intensive industries that disrupted production there more than in other euro area countries, particularly in the chemical sector.”

However, even if German firms reduced their reliance on natural gas to the same intensity as in the processes followed by their European competitors, they would still remain uncompetitive: the peculiarities of the current German energy infrastructure render the usage of LNG inherently more expensive than in other countries.

The term “current infrastructure” should not overstate the feasibility of alternative gas delivery schemes. The obvious approach is to establish land-based LNG terminals, and discard FSRUs. Such onshore terminals take typically 4 years to build, imply a commitment to LNG during decades (50 years or so), and require an initial capital outlay that is an order of magnitude larger than for FSRUs. One such project in Stade is supposed to be completed in 2027, another one in Wilhelmshaven is supposed to start in 2026. It is doubtful whether the German industry can sustain several years of uncompetitive gas prices before those terminals are in place. This could leave Germany with further stranded assets in the form of brand-new onshore LNG terminals.

The other approach is to procure gas from other sources via pipelines.

Germany already procures as much as it can from the North Sea. Norway, the Netherlands, and Belgium are the largest suppliers of gas to Germany — LNG comes only fourth. The problem: Dutch gas fields are getting depleted or closed because of geological problems, and there is hefty competition for the output of the Norwegian ones (e.g. Poland put in service the Baltic Pipe bringing in gas from Norway).

What is left is returning to the pre-2022 situation: acquiring large quantities of cheap gas from Russia.

If the gas is to come via pipelines crossing Ukraine, then this requires an end to the war and the establishment of a stable, trustworthy Ukrainian government. Unlikely in the short term.

If the gas is to come via NordStream, then this requires the new German government to break with the currently rabid russophobic atlanticism, to re-establish sane relations with Russia, and to repair or put in operation the exploded pipelines as quickly as possible. It does not look as if German politicians would dare going this way, as they would face the furious opposition of Baltic, Scandinavian, and Anglo-Saxon countries, as well as of Poland and Ukraine (implying possibly more unexplained bombings of energy infrastructure); and it looks as if a mysterious Stephen P. Lynch from the USA is trying to get the ownership of the assets from the bankrupt Nord Stream 2 AG anyway.

Whichever expression one chooses — cutting off the branch you’re sitting on, committing seppuku — it looks as if whole swathes of the German industry were dealt a death blow purely for ideological reasons.

This article came to my attention via The Honest Sorcerer, which mentioned it in the latest piece there. I’m not very fond of the orthodox methodology by the authors, but the spillover concern clearly is important and should be taken into account. It’s hard to imagine a functioning EU without the industrial might of Germany, after all.