Yves here. While this post flags an important central finding, that the more a job is exposed to AI use, the longer its hours become, its authors seem awfully credulous about the supposed benefits. Specifically, they consider that the additional time required is to clean up AI messes due to fad-enamored managers requiring its use when it is not ready for prime time.

For instance, earlier this year, IM Doc reported on the train wreck of AI writing up patient visit notes which seem entirely plausible (as in accurate) Wwhen rife with serious errors. And that is routine. From his e-mail:

The visits are now being recorded and about 10 minutes later – the AI generated visit notes appear in the chart. On almost 2/3 of the charts that are being processed, there are major errors, making stuff up, incorrect statements, etc. Unfortunately – as you can see it is wickedly able to render all this in correct “doctorese” – the code and syntax we all use and can instantly tell it was written by a truly trained MD.

I have noted to my dismay that most of my colleagues do not even look at these – they simply sign off on them. That is a fatal tragedy.

He then recounted a particular case, with enough anonymized backup to support his claims.

The patient had come for a routine visit. No new issues, a recitation of routine aches and pains, and a review of recent bloodwork and other regular tests.

The AI invented that the patient was on dialysis when the patient had never had kidney issues. There there was no discussion of renal issues or tests in the visit, much the less the AI’s claim that a congenital defect caused the (supposed) kidney issues. It also claimed the patient had had a particular operation (falese) and had recently been septic. The AI also depicted the patient as unable to drive due to cataracts resulting from the administration of steroids, another fabrication.

As IM Doc pointed out:

1) Had I signed this and it went in his chart, if he ever applied to anything like life insurance – it would have been denied instantly. And they do not do seconds and excuses. When you are done, you are done. If you are on dialysis and have cataracts and cannot drive – you are getting no life insurance. THE END.

2) This is yet another “time saver” that is actually taking way more time for those of us who are conscientious. I spend all kinds of time digging through these looking for mistakes so as not to goon my patient and their future. However, I can guarantee you that as hard as I try – mistakes have gotten through. Furthermore, AI will very soon be used for insurance medical chart evaluation for actuarial purpose. Just think what will be generated.

3) These systems record the exact amount of time with the patients. I am hearing from various colleagues all over the place that this timing is being used to pressure docs to get them in and get them out even faster. That has not happened to me yet – but I am sure the bell will toll very soon.

4) When I started 35 years ago – my notes were done with me stepping out of the room and recording the visit in a hand held device run by duracells. It was then transcribed by secretary on paper with a Selectric. The actual hard copy tapes were completely magnetically scrubbed at the end of every day by the transcriptionist. Compare that energy usage to what this technology is obviously requiring. Furthermore, I have occasion to revisit old notes from that era all the time – I know instantly what happened on that patient visit in 1987. There is a paragraph or two and that is that. Compare to today – the note generated from the above will be 5-6 back and front pages literally full of gobbledy gook with important data scattered all over the place. Most of the time, I completely give up trying to use these newer documents for anything useful. And again just think about the actual energy used for this.

5) This recording is going somewhere and this has never been really explained to me. Who has access? How long do they have it? Is it being erased? Have the patients truly signed off on this?

6) This is the most concerning. I have no idea at all where the system got this entire story in her chart. Because of the fake “Frank Capra movie” style names in the document [inclusion of towns and pharmacies that do not exist] I have a very unsettled feeling this is from a movie, TV show, or novel. Is it possible that this AI is pulling things “it has heard” from these kinds of sources? I have asked. This is not the first time. The IT people cannot tell me this is not happening.

Admittedly, to the authors’ credit, they do discuss one downside that IM Doc highlighted: that of even more extensive/intensive management surveillance.

By Wei Jiang, Junyoung Park, Rachel Xiao and Shen Zhang. Originally published at VoxEU

Technological progress is typically expected to lighten the burden of work. But as artificial intelligence has been integrated into workplaces, early evidence suggests a paradox: instead of reducing workloads, many AI-equipped employees are busier than ever. This column examines the relationship between AI exposure, the length of the workday, time allocation, and worker satisfaction. Though AI-driven automation and delegation allow workers to complete the same tasks more efficiently, the authors find that employees in AI-exposed occupations are working longer hours and spending less time on socialisation and leisure.

For much of modern history, technological progress has been expected to lighten the burden of work. Keynes (1930) predicted that by 2030, rising productivity would allow people to work 15 hours a week. As artificial intelligence is integrated into workplaces, early evidence suggests a paradox: instead of reducing workloads, many AI-equipped employees are busier than ever. While AI-driven automation and delegation allow workers to complete the same tasks more efficiently, employees in AI-exposed occupations might well be working longer hours and spending less time on socialisation and leisure.

The rapid diffusion of AI, exemplified by the introduction of ChatGPT in late 2022, has reignited concerns about its effects on employment. A large body of work examines how AI is replacing some job functions while augmenting others – the extensive margin of employment (e.g. Acemoglu et al. 2022, Albanesi et al. 2023, Bonfiglioli et al. 2024, Felten et al. 2019, Gazzani and Natoli 2024). Less attention has been given to how AI influences time allocation – the intensive margin of employment. If workers retain their jobs, does AI make them work more or less? Our study (Jiang et al. 2025) examines the relationship between AI exposure, the length of the workday, time allocation, and worker satisfaction.

Using nearly two decades of time-use data from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), we link AI-related patents with occupational descriptions to construct a measure of AI exposure across jobs. We then distinguish AI that complements human labour – enhancing worker productivity – from AI that substitutes for it, potentially displacing workers.

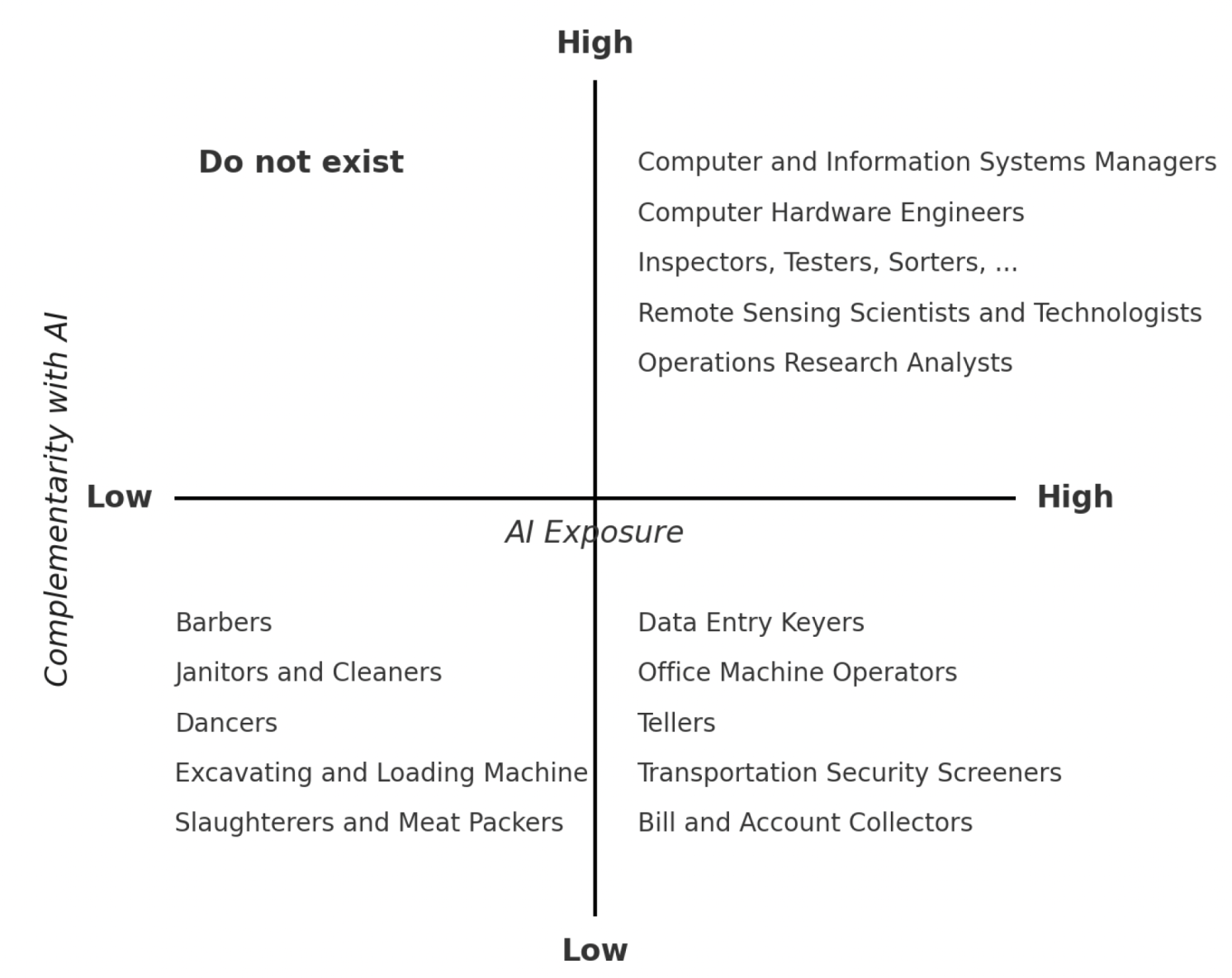

AI complementary/substitutive exposure varies significantly across occupations, as illustrated in Figure 1. At the forefront are computer and information system managers, bioinformatics technicians, and management analysts, fields where AI enhances productivity rather than substituting labour. In contrast, jobs like data entry keyers, tellers, and office machine operators face high AI substitutive exposure but little complementarity, facing the risk of displacement rather than augmentation. Meanwhile, occupations such as dancers and barbers sit at the bottom of the AI spectrum, largely untouched by AI advancements.

Figure 1 Complementarity with AI

A third category of AI exposure – AI-driven monitoring – captures how surveillance technologies track employee effort. This framework allows an examination of whether AI lengthens or shortens the workday and whether these effects vary across labour markets.

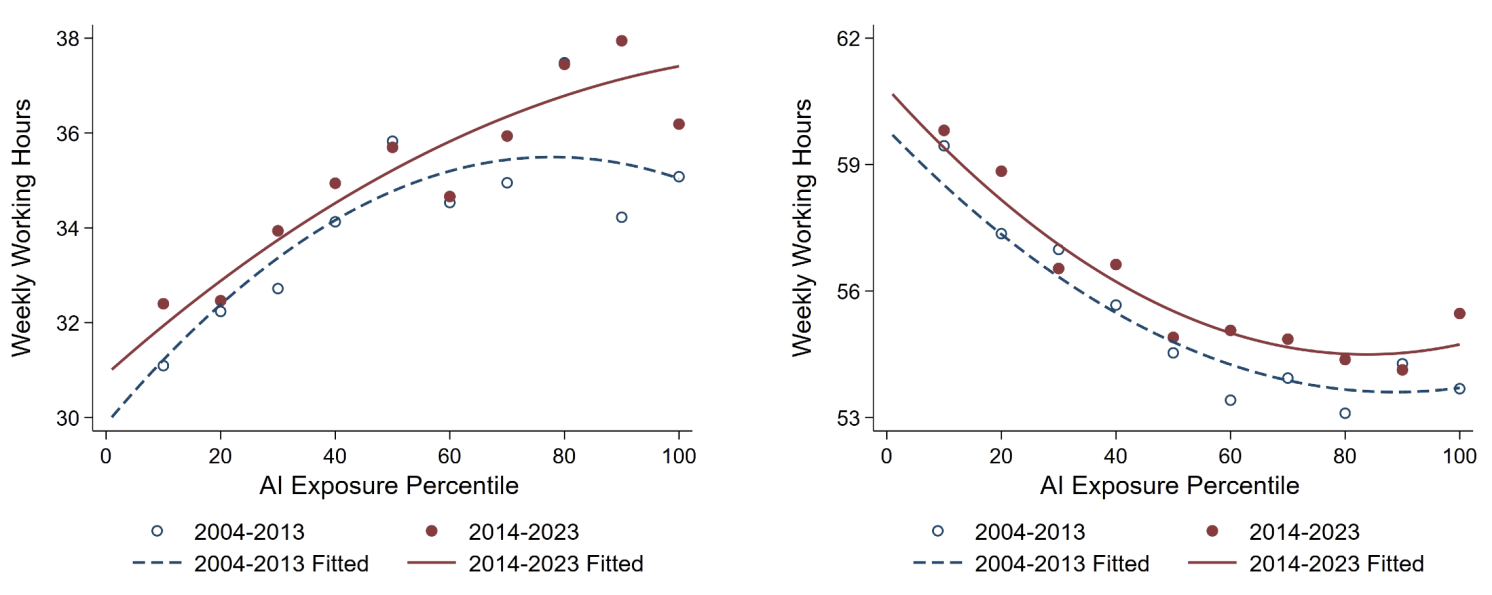

The findings, summarised in Figure 2, reveal a pattern: higher AI exposure is associated with longer work hours and reduced leisure time. Over the 2004–2023 period, workers in AI-intensive occupations increased their weekly work hours relative to those in less exposed jobs. An increase from the 25th to the 75th percentile in AI exposure corresponds to an additional 2.2 hours of work per week. This relationship is strengthened over time, suggesting that as AI becomes embedded in workplaces, its effect on working hours intensifies. This challenges the expectation that automation enables workers to complete tasks more quickly and reclaim leisure time.

Figure 2 Weekly working hours and AI exposure

The introduction of ChatGPT provides an unexpected shock to generative AI adoption and serves as a natural experiment (Hui et al. 2023). Occupations more exposed to generative AI saw a rise in work hours immediately following the release of ChatGPT. Compared to workers less exposed to generative AI (such as tire builders, wellhead pumpers, and surgical assistants) those in high-exposure occupations (including computer systems analysts, credit counsellors, and logisticians) worked roughly 3.15 hours more per week in the post-ChatGPT period. This shift was accompanied by a decline in leisure time, reinforcing the idea that AI complements human work in a way that increases labour supply rather than reducing it. When leisure hours are cut, non-screen-based activities – especially entertainment and socialisation – bear the brunt. Screen-based leisure activities, such as watching television and playing video games, remain relatively stable, suggesting that workers are more likely to sacrifice activities that require active participation rather than passive consumption, signalling a shift towards more isolated and sedentary downtime.

Two key mechanisms help explain this result. First, AI raises worker productivity, creating incentives for longer hours. When AI complements human labour rather than replacing it, the process makes each hour of work more valuable. This effect is strongest in jobs where AI helps employees perform tasks more efficiently, such as finance, research, and technical fields. Employers may expect more output; workers, incentivised by productivity-linked pay, may extend their hours. AI-exposed occupations have indeed seen wage increases, suggesting that firms are sharing some productivity gains. However, higher wages have not translated into more leisure time. Instead, workers appear to be substituting additional earnings for longer hours, a pattern consistent with the economic principle that when work becomes more rewarding, people may choose to do more of it.

The second mechanism is AI-driven performance monitoring. Digital surveillance tools have expanded, particularly in remote and hybrid work environments. AI enables real-time tracking of employee effort, leading to longer working hours. Our study examines the COVID-19 period as a natural experiment, when AI-driven monitoring surged due to remote work. Jobs that were more ‘remote-feasible’ at the onset of COVID-19 experienced dramatic improvement in remote work monitoring during the next two years. Occupations with high exposure to AI surveillance technologies – such as customer service representatives, stockers and order fillers, dispatchers, and truck drivers – experienced longer work hours post COVID even after workers returned to the office. This effect was absent among the self-employed, confirming that it is not simply the nature of AI-exposed jobs but the principal-agent dynamics of employment that drive longer work hours. Monitoring increases employer oversight and tightens performance expectations, often at the cost of work-life balance. Some AI-intensive roles saw the introduction of automated performance scores, leading employees to work harder to avoid falling behind peers in algorithm-driven assessments.

The broader question is: who benefits from AI-driven productivity gains? While AI-exposed workers may see wage increases, these gains do not translate into improved wellbeing. Employee satisfaction data from Glassdoor show that higher AI exposure is associated with lower job satisfaction and work-life balance ratings. While AI may boost output and compensation, it does not necessarily enhance workers’ quality of life. Many of AI’s productivity gains accrue to firms and consumers rather than to workers.

Labor and product market competition shapes these dynamics. First, AI’s impact on work hours is amplified in competitive labour markets, where workers have less bargaining power because there are only a few employers who dominate local hiring. In such environments, employees are less able to demand shorter hours or better compensation for increased productivity. Second, in highly competitive product markets (where products in the industry are similar), firms have an incentive to pass productivity gains on to consumers in the form of lower prices or better services, rather than sharing them with workers through reduced workloads. The result is that while AI makes workers more productive, they do not necessarily see corresponding improvements in work-life balance. Instead, they work more hours to maintain their employment.

AI’s role in the future of work is not predetermined. The extent to which it leads to longer or shorter hours depends on how firms deploy the technology and how policymakers respond. Our research provides insight into this debate, showing that AI is not inherently liberating or oppressive. The impact of AI on work hours is shaped by the incentives and constraints of labour, product, and capital markets. If AI is to improve lives, more deliberate and well thought-out approaches will be necessary to distribute its benefits fairly.

See original post for references

There are a lot of people who are unreasonably optimistic about AI and what it can do regardless of context. For example, I’ve sat through a lot of presentations recently where people are excited about the potential of AI to revolutionize scheduling and project management in construction. But the reason why they want to apply AI to find efficiencies is because we don’t have people to do the work. At the end of this it feels like we’ll have someone’s definition of a perfect plan which can’t be executed because there’s no one to do the work. We’re also still struggling against so many different versions of NIMBYism that I’m not sure what you’d do to account for that with an AI tool. Fuzzy logic doesn’t begin to describe it.

The conversations around AI and this article are the most bizarre things I’ve experienced with respect to tech. Futurism is typically positive and optimistic. AI applications stem from being optimistic about it preventing things from getting too bad on one hand while destroying things for someone else on the other. “Yes, we’ll be able to keep productivity up and minimize repairs using AI. Shame about all the people who will starve though.” This thing being shoved down our throats isn’t Star Trek.

With respect to transcription, I have found ways to make it work given limited resources. For example, if you have a recording and you can compare the transcript to the recording so that you catch the phonetics and other errors in the AI transcript then it’s useful to have the service. But, that’s only from the perspective that you didn’t expect to get a transcript or you weren’t going to be able to get a transcript that quickly. I’ve found these kind of things are useful tools for recording talks and presentations from old timers who are retiring. People who I want to be able to talk to about their insights, or to capture their thoughts for the next generation to learn from.

When dealing with anything that needs an accurate record and no voice recording is available, human transcription remains the key. AI can’t handle it for deposition transcripts for instance.

Fellow Chris, from my PoV the problem that the AI enthusiasts refuse to address is risk/liability.

Who bears liability, when:

1. AI kills a patient?

2. AI is used to draw up blueprints for an architectural project, and the building collapses?

3. AI is used to create a defense for a criminal, and ends up committing legal malpractice, resulting in imprisonment of the defendant.

Sam Altman’s answer is – we do! We’re simply going to have to eat it, you, me, IMDoc. It’s all part of the sacrifice for a beautiful future where humans no longer have to think.

It’s up to the gate keepers like the AMA and the ABA along with all of us to stop this. Use of AI in critical fields that involve human life should be banned.

I agree Fellow Chris, those are all important questions. I think that Mr. Altman’s answer is he doesn’t care who is responsible as long as it isn’t him and doesn’t cost him money.

But from that congressional notice we saw a month or so ago, people are moving to make it legal for algorithms and robots to at least be pharmacists without human intervention. I feel like doctor’s and other professions will follow.

>>>Sam Altman’s answer is – we do! We’re simply going to have to eat it, you, me, IMDoc. It’s all part of the sacrifice for a beautiful future where humans no longer have to think.

So, we will become the Eloi as long pork for the Tech Lords or biofuel for our AI Gods?

As far as I remember the George Pal movie, at least the Eloi didn’t have to work.

The concluding paragraph has this bit:

Since policymakers (legislators?) have not in the past 40 years bothered to create policy (legislate) influence where productivity gains goes then it might be assumed that they will continue to do the same – nothing. And if they do nothing then the benefits will go to the ones with the strongest bargaining position & that is the employer. For me the outcome is predetermined as policymakers lets the market decide policy.

Anyway, from what I have seen of IT-projects with the intent of improving productivity (AI and automation) then they often fail due to IT people lacking understanding of underlying processes and the ones who do have the understanding either don’t provide it as it might make them redundant or they do provide it but the IT people ignores the people who are closest and are actually using the underlying processes.

Failed IT-implementations aren’t failures for consultants as they continue to get billable hours and aren’t failures for the people who would have been made redundant if the IT-implementation had been a success….

So therefore I expect many failures and a few successes. Over time then maybe in the long term the successes will have out-competed the failures.

From IM Doc’s quote;

This is not a criticism of IM Doc’s observation, but “IT people” is a label that doesn’t explain enough about the people, and their way too many separate skill sets, and their complicated relationships, all related to the systems being discussed.

The “IT people cannot tell me this is not happening.” are most likely local network support, or maybe in-house first level software support, or maybe first level software support from the system vendor, all delivered remotely by people who cannot be expected to know what’s going on because they had and have nothing to do with the team that programmed it in the first place, or maintain it now.

The people who answer the phones when you call support don’t have much contact with the programmers, it takes a while, but the problems you report find their way to somebody’s job schedule eventually, big, profit threatening problems/solutions move faster of course. What I’m saying is that there is, at every level, an incentive to deny* or minimize the problems, all the while working feverishly to fix them.

The problems IM Doc describes are so horrendous they are hard to imagine.

And that brings up, arguably the most important group, the people who paid for, and profit from the system’s operation.

These are the guys who send the programmers home before the product is proven ready for prime time, and the guys who lied to you when they sold it to you, and these are the guys who tried for months to convince you it was your fault, and now these are the guys who think hooking the already evil digital health record system they sold you, up to a tech fad/fraud like AI will end up being a great idea.

These guys might own the hospital IM Doc works for, and the software vendor he’s being forced to use, and the whole works might be owned by a health insurance company.

This is hard to imagine.

*nobody ever admits being hacked.

IM Doc provided an image of the transcription and the patient records with identifying info scrubbed. My summary is less graphically bad than the transcription was.

IM Doc, I’m only guessing here but I suspect your outputted notes are the result of 2 layers of AI which in the end only enhances the garbage in garbage out.

The first layer of AI is the voice to text. I love to read the transcribed voice mails of my mother because Apple just doesn’t understand what she’s saying. Often her transcribed messages are X rated even though she never actually said anything X rated, it just got butchered in translation.

In your case, this “butchered translations” (your recorded notes) is likely being feed into another AI process to populate the final notes.

We all have to remember AI is not sentient intelligence (it’s NOT intelligent, that’s a lie). The AI process taking in your F’d-up transcriptions of your voice recording isn’t like me laughing at how awful the transcription was. It’s taking it in like it’s fact. And hence your patients are deemed so ill as to need 5-6 pages of notes for diseases you never actually said they had.

In short… Voice in.. AI transcription garbage out… Garbage in for AI notes… final AI notes.. garbage out.

5 – 6 pages of gobbledygook? Some corporate big wigs KPI (and resulting bonus) just went thru the roof. Corporate America is going to implement this AI every place it possibly can. And there are so many places because workers in many corporate settings are required to keep extensive records and then never given the time or means to actually do it.

GIGO may have to be modified to indicate AI in, fantasy out wherever appropriate.

Is there a missing “don’t” in the 2nd sentence of the intro? – …”…they [don’t] consider that the additional time…”

Because I agree – after presenting the data, the author of the article then interprets increased work hours as being due to AI working so well. My own experience is similar to IM Doc’s – now that I’m required to use “AI” for certain tasks, they now take longer because I need to correct all the mistakes rather than just doing it right myself the first time.

No doubt an additional layer of hidden labor this nonsense technology will add to is “self-sourced.” I spend enough time on the phone speaking to costumer service representatives (or trying to get them on the phone) about billing mistakes and the number humans replaced by bots is already infuriating.

Yesterday we had our upcoming product release planning meeting where the program director readily admitted that Ai implementation in our software has resulted in more confusion for the user experience as studies from our beta program showed. Search, especially, was singled out as results from a query will essentially spit out almost all operations available and most having no relation to what the user was asking for. The old days of manually filling out meta tags with keywords was much more effective and has proven to be less time-consuming.

Like Yves’ opening paragraph, Ai is being driven by the corporate mgmt with very little developer input as to the need for embedding this tech in our products. Looks like we’re stuck with this turd for the duration…

TL;DR for what follows- The problem, as usual, is not the technology but the people developing and deploying it. We’re talking the same rentier capitalists who routinely exploit every new technological development to further extract wealth and assert control. All the issues described by the doctor are not intrinsic to AI but intrinsic to AI irresponsibly and unethically deployed.

Longer Version:

I guess I’m one of those folks who occupy the upper right quadrant in the Complementarity / Exposure matrix – I’m a technical program manager who has been working on fairly complicated software and technical infrastructure projects for the past 30 years. I also happen to be much more upbeat / optimistic about the value of AI systems when used responsibly and ethically.

And therein lies the catch: In the current U.S. regulatory climate it is highly unlikely that AI will be designed or deployed responsibly or ethically, even more so in the “walled garden” scenarios where the technology remains a black box to everyone except the corporations which own them – i.e., the Mag 7.

By contrast, I would strongly encourage readers of this article to take a look at the EU AI Act, currently under review and scheduled for implementation in 2026. Like the GDPR before it, the EU AI Act addresses precisely the types of concerns raised in the article, particularly with regard to “high risk” utilization categories. It is also far more demanding on corporations than on open source developers and deployers of AI technologies, having clearly taken some lessons from corporations repeatedly violating GDPR.

Where the Act falls short is in its silence on the impact of AI systems on labour, though it may be the case that these concerns are covered in other EU regulations I’m currently unfamiliar with. Either way, the fact that tech bro fan boys are railing against the EU AI Act is a clear indication that it will have a positive impact reining in the wild west, everything goes Mag7 / Silicon Valley tendencies.

I also want to add that China finds itself occupying the ethical high ground on AI development, as evidenced by the pronouncement at the 2024 Shanghai World AI Conference: “We underline the need to promote the development and application of AI technologies while ensuring safety, reliability, controllability and fairness in the process, and encourage leveraging AI technologies to empower the development of human society. We believe that only through global cooperation and a collective effort can we realize the full potential of AI for the greater well-being of humanity.” Coupled with the recent release of DeepSeek open source AI technology, a grenade thrown into the Mag7 walled gardens, China’s push for affordable and sustainable open source AI technology will go some way towards creating a more responsible and ethical environment for developing and deploying AI solutions that are not opaque and toxic.

While I agree mostly with your views, I don’t see the answer as regulatory because the cunning will always find a way round. Nor by asking for less opacity in the technology as AI is inherently opaque in that the initial training phase generates a model (a numeric dataset) which is then utilised by the application, matching the input data to this model in some way. There is no code to follow, no algorithms – just numbers. It is no wonder IM Doc’s IT staff could not tell what the source of the model was – only the model trainers would know.

One answer therefore would be to set standards that an AI (or other program) must achieve before receiving some kind of certification. It would be up to the developer to state what the software would do, and to what level of accuracy, and to provide suitable test data to demonstrate compliance. There would need to be official verification.

And of course, no EU government (or publicly-funded organisation) could use non-certified (AI) software.

It is usual when AI makes an inference (such as “this patient has cataracts”) that it also makes a prediction of how accurate this inference is – a confidence score.

Unfortunately if the output is textual (Word document or similar) then the meta-information, including confidence scores, is missing. You need some sort of marked-up output such as XML to get all the information, and this is not very human-friendly. However, it could drive a “Patient Notes Editor” or whatever to highlight suspect passages (low confidence score) before the human expert signs off on the notes.

The problem here is that the AI system can do a good job of transcription with high confidence, a good job with low confidence, a poor job with low confidence and – worst of all – a poor job with high confidence that it is right. The first case is fine – working as expected. The second is just a time-waster, having to check good work. The third is also OK as mistakes are picked up. The last case is terrible – it means you cannot actually trust the software at all.

There is an answer to this accuracy problem and that is to use multiple AI systems in parallel, all using different methodologies, and compare the results (ensemble programming). Of course using say, six different systems means more than six times the cost which might be a downside.

As a final thought on cost and who bears it – read any software licence from 1980 on to see how accountable programmers are (or don’t bother. The answer is not.)