Yves here. This post of the collateral damage, as in unnecessary deaths and other damage done to patients when hospitals are overloaded by climate extreme episodes has more general application. This piece shows that excess mortality, resulting from the rationing of hospital care, can be parsed out from the heat effects and are significant.

This outcome was evident in New York City during “wild type” Covid in 2020. Then, patients that wound up hospitalized often were on a 2-3 week path to death as their lungs turned into bloody goo. That is a far longer time of hospital bed occupancy than is normal, hence planned for. And thanks to neoliberalism, cutting the number of hospital beds had become a priority. That means that even if enough doctors and nurses could have been marshaled to handle the horrible surge, the physical plant would constrain how many sick and injured could be handled. In NYC, during Peak Covid, there were many reports of 36+ hour waits merely to be attended to in an emergency room, and these delays were pervasive. This sort of wait for a stroke or heat attack or accident victim is dangerous to deadly.

The author point to the obvious need to increase hospital capacity to cope with a higher and set-to-rise level of extreme events. But despite the cost of inaction, what will it take to get this done?

By Sandra Aguilar-Gomez, Joshua Graff Zivin, and Matthew Neidell. Originally published at VoxEU

As extreme heat events become more frequent and severe, rising temperatures will increase the incidence of heatstroke, kidney damage, and cardiovascular stress. This column considers extreme heat as not only a direct health threat, but also a systems-level shock that will expose and exacerbate existing vulnerabilities in healthcare delivery. To prepare for a future of acute heatwaves, policymakers and healthcare leaders must ensure that hospitals operate effectively during these crises. Addressing the indirect effects of climate change is an essential component of broader climate adaptation efforts.

As climate change accelerates, extreme heat events are becoming more frequent and severe, posing substantial health risks. Policymakers and public health experts are well aware that rising temperatures increase the incidence of heatstroke, kidney damage, and cardiovascular stress. Yet, a critical dimension remains underappreciated: how extreme heat strains healthcare systems and compromises patient outcomes. While previous studies have documented the direct effects of heat on morbidity and mortality (Basu 2009, Deschenes 2014, Geruso and Spears 2018), our research highlights a crucial but thus far overlooked spillover effect: the way heat-driven hospital congestion exacerbates health risks, even for patients whose conditions are unrelated to temperature exposure (Aguilar-Gomez et al. 2024).

The Overlooked Consequences of Extreme Heat on Healthcare Systems

When a heatwave strikes, hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) often experience a sharp rise in patient inflows. A growing body of research has shown that hospital overcrowding can have serious consequences for patient care. For example, studies of flu outbreaks (Gutierrez and Rubli 2021) and pollution-driven surges in paediatric hospitalisations (Guidetti et al. 2024) reveal a troubling pattern: when demand exceeds capacity, delays in treatment, premature discharges, and higher mortality rates follow.

Building on this literature, our research (Aguilar-Gomez et al. 2025) examines how extreme heat affects hospital congestion and patient outcomes in Mexico, a country that provides a particularly relevant setting for this study as healthcare resources are often constrained and the frequency of extreme heat events is projected to rise disproportionately compared to higher-latitude nations (Desmet and Rossi-Hansberg 2024, Murray-Tortarolo 2021, Pörtner et al. 2022, Robert-Nicoud and Peri 2021). Our findings suggest that hospital overcrowding during heatwaves is not just an operational challenge – it is a major driver of excess mortality, including among patients whose conditions are unrelated to heat exposure.

How Heat Waves Disrupt Hospital Systems

We leverage an extensive dataset over an eight-year period (2012–2019), including records of all emergency department and hospital visits at Ministry of Health (MoH) facilities, which serve two-thirds of Mexico’s population. By linking health data with weather records, we examine how spikes in temperature influence hospital admissions, patient transitions within the healthcare system, and health outcomes.

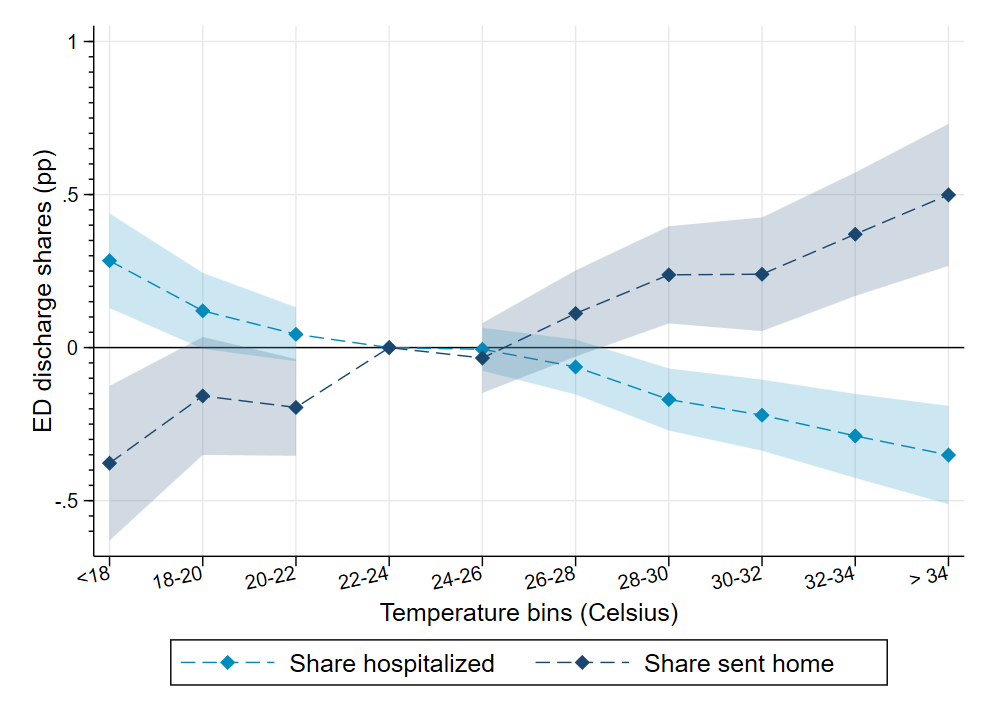

The effects are striking. When daily maximum temperatures exceed 34°C, ED visits increase by 7.5% (approximately three additional visits per day), and hospitalisations rise by 4%. Faced with this surge, hospitals appear to ration care. Figure 1 shows that as temperatures rise, the likelihood that an ED patient is admitted to the hospital decreases while the share of patients sent home increases, suggesting that hospitals are reaching capacity.

Figure 1 Changes in triage of ED patients

Further, extreme heat accelerates patient discharges, likely as a response to overcrowding. Our findings indicate that hospitals reduce the average length of stay on extreme heat days, discharging more patients early to free-up beds. More worryingly, patients sent home on these days tend to be less healthy than those discharged on cooler days, raising concerns about their post-discharge health outcomes.

The Hidden Toll: Excess Mortality Due to Heat-Driven Overcrowding

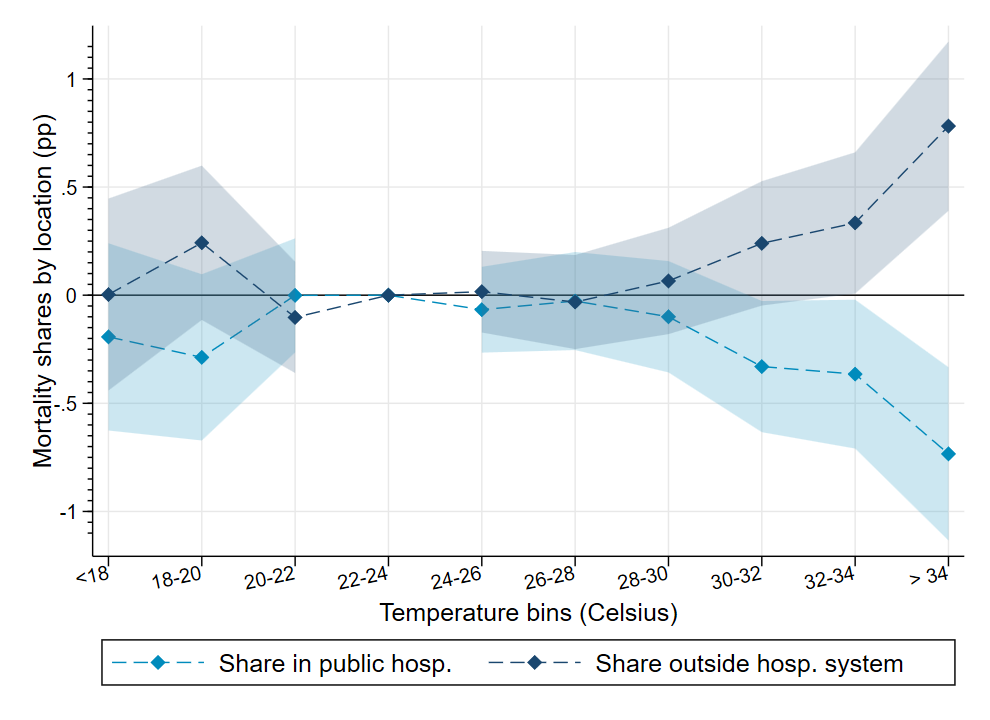

While some observers might assume that those discharged early or turned away from the ED can seek care elsewhere, our findings suggest otherwise. Using vital statistics data, we find that mortality rates rise both inside and outside hospitals during extreme heat events. Figure 2 shows that deaths outside the hospital increase at a greater rate than those within it, consistent with a scenario in which critically ill patients are discharged prematurely or denied admission due to overcrowding.

Figure 2 Share of deaths by location

To isolate the role of hospital congestion from direct heat-related effects, we examine excess mortality among patients already hospitalised before a heatwave begins. Even among this group, an additional day with temperatures exceeding 34°C increases mortality by 5%, suggesting that hospital crowding, rather than heat exposure itself, is the key driver of these deaths. Additional analyses focused on cancer patients (who should not be physiologically vulnerable to temperature fluctuations) yield similar results, reinforcing the congestion hypothesis.

Policy Implications: Adapting Healthcare Systems to a Warmer Future

Residential air conditioning has been a key focus of climate adaptation discussions, along with other tools such as changing urban structure or climate-proofing transport systems (Barreca et al. 2016, Costa et al. 2024). Our findings highlight an overlooked avenue for climate adaptation: strengthening healthcare system resilience. Ensuring that hospitals can handle climate-induced surges in demand is equally critical. This may involve expanding hospital capacity, increasing staffing during heatwaves, and improving surge management protocols. The stakes are particularly high for developing countries, where access to air conditioning is limited (Escobar et al. 2025), the mortality impacts from extreme heat are highest (Geruso and Spears 2018), and healthcare systems are already overburdened.

Investing in hospital infrastructure and workforce expansion could mitigate not only the direct health effects of climate change but also the spillover consequences of hospital congestion. Moreover, improving patient triage and care coordination could help alleviate pressure on hospitals during extreme heat events, reducing the risk of premature discharges and preventable deaths.

Conclusion

Extreme heat is not only a direct health threat, it is also a systems-level shock that exposes and exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in healthcare delivery. Our research underscores the importance of recognising and addressing these indirect effects as part of broader climate adaptation efforts. As policymakers and healthcare leaders prepare for a future with more frequent and severe heatwaves, ensuring that hospitals remain functional and effective during these crises will be paramount. Investing in healthcare resilience today could save lives tomorrow.

For more details, readers can refer to our full study (Aguilar-Gomez et al. 2025), which provides a deeper dive into the methodologies and data underlying these findings.

See original post for references

Yeah this resonates. I got “wild type” COVID at the very start of the pandemic in Feb 2020. I was in extreme respiratory distress overnight but did all the things I knew to try to regulate my breathing etc and avoiding calling 999 for an ambulance because our local hospital was the LAST place I wanted to be.

Climate “weirdness” has definitely occurred at times of the year when the hospital has been “code black” (meaning it is officially overloaded and ambulances must divert). We got heavy snow in December….. in my 50+ years I can’t remember more than one similar phenomenon: if it snows it is almost always Feb or March. Now we are getting daytime spring temperatures of 19 Celsius here in middle of England. Totally freaky.

With mass cases of extreme heat casualties, I wonder if it would be worthwhile to set up tents outside the hospital building itself which would have mist sprayers set up in the top of the tent spraying down. It would not be rocket science designing such a system. for mass deployment. It might serve to cool down a lot of people and let any doctors or nurses doing triage spot those that are really in distress and need to go into the hospital itself. It would be something like this but on a much larger scale-

https://bigfogg.com/mid-pressure-misting-tent-standard/

Agreed but they’d lose all that income from exorbitant car parking fees. /snark

Depends on the wet bulb temperature. It won’t work in high heat and humidity.

In the US, I can imagine a scenario where multiple events line up and the power grid can’t provide the electricity for cooling. Like major storms or massive tornado outbreak, followed by a record hot and humid week. Or major wildfire in the West affecting power generation and/or transmission, followed by a massive heat wave.

Then there are the areas without widespread A/C, like India, Pakistan, around the Persian Gulf, etc.

Yeah the wet bulb temperature thing is the thing I’ve always thought of as the elephant in the room. This will kill millions if not billions if we carry on as normal.

In the neoliberaism universe, hospitals are at 102-105 capacity ALL the time…