This time, it’s not just Wall Street banks that should be worried about the contagion risks from a full-blown banking crisis in Mexico. So, too, should their European counterparts.

Moody’s has changed the outlook of the Mexican banking system from positive to negative due to the ongoing tariff tensions with the United States and the country’s economic slowdown. The US ratings agency cited a number of reasons for the change in outlook, including Mexico’s slowing economic growth, driven apparently by reduced public spending and market-unfriendly institutional changes. Trump-induced uncertainties surrounding trade relations with the United States are also contributing to macroeconomic pressures and lower business volumes.

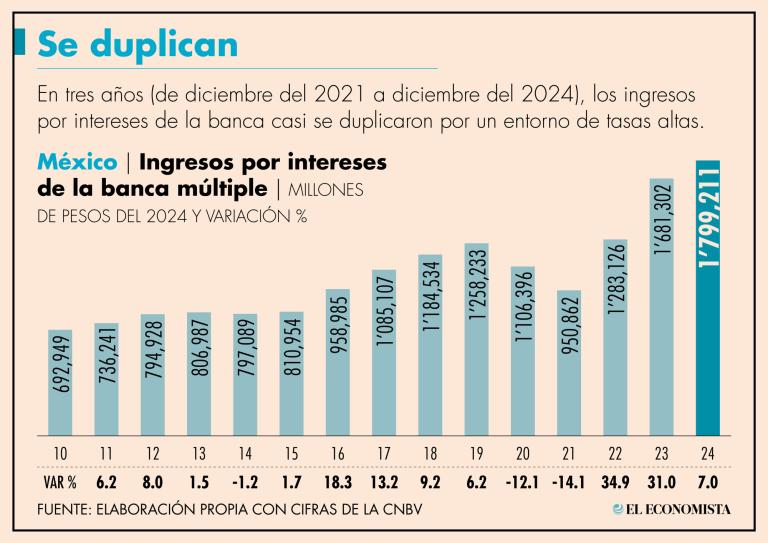

These trends are all likely to heap further pressure on an already slowing banking sector. A three-year surge in banking sector revenues, driven largely by higher benchmark interest rates, already began slowing last year, as the graph below, courtesy of El Economista, shows. Not coincidentally, in March last year the Bank of Mexico began the process of reversing rate rises. A year on, rates are now at 9.5%, 200 basis points below their former 11.5% peak.

[Translation of accompanying text: in three years (from December 2021 to December 2024), the banks’ net interest income almost doubled due to the higher-rate environment].

The Moody’s report also underscores the Mexican government’s waning capacity to provide economic support due to its weaker fiscal position as well as the potential economic impact of recent reforms to the country’s institutional framework. They include the judicial reforms that passed by a whisker last Autumn, almost sparking a constitutional crisis in the process — a topic we covered in some detail here, here and here.

The judicial reform was the foundation stone of former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s reform agenda. It was also a stepping stone, allowing for the reversal of the corporate capture and control of the country’s judiciary. Now, the Sheinbaum government can begin focusing on passing its other proposed reforms in areas such as energy, mining, fracking, GM crops, labour laws, housing, indigenous rights, women’s rights, universal health care and water management.

Suffice to say, many of these reforms are bitterly opposed by the business elite, both foreign and domestic. If fully implemented, they will limit the ability of corporations, particularly in the mining sector, to extract wealth at exorbitant social and environmental cost. For decades corporations have been able to count on the support of a pliant judiciary that has faithfully served and protected the interests of the rich and powerful. That now appears to have changed, but it is already having an impact on how foreign investors and ratings agencies view Mexico.

The Biggest Threat

Moody’s also flagged the rising risk of state oil company Pemex’s contingent liabilities materializing on the government’s balance sheet. Mexico is currently two notches off losing its investment grade rating with Moody’s and S&P and just one away from losing it with Fitch Ratings.

Granted, when it comes to the pronunciations of US credit ratings agencies, a disclaimer is needed. As was shown in the subprime crisis, when rating agencies like Moody’s were giving triple-A ratings to mortgage backed securities that were found later to be nothing but dog **** (to quote from our resident Rev Kev), the sector is riddled with conflicts of interest. It is also hard to shake the feeling that this sort of report is aimed more at putting pressure on Mexico to adopt Wall Street friendly policies than providing a true reflection of Mexico’s economic health.

The irony is that the biggest risk to Mexico’s economic health comes from the Trump Administration’s constant threats of tariffs, mass deportations and military intervention. As Moody’s warns, US tariffs could harm Mexico’s manufacturing, automotive, and technology industries. These disruptions may lead to currency depreciation, increased inflation, and constraints on interest rate cuts, which would in turn dampen loan demand. The resulting volatility in exports, exchange rates, and inflation could also reduce banks’ risk appetite.

Even though most of the tariffs have yet to be implemented for any meaningful length of time, they are already causing acute economic uncertainty between the US and its largest trade partner, Mexico. Last week, Roberto Lyle Fritch, the president of the Business Coordinating Council (CCE), one of Mexico’s largest business lobbies, warned that the persistent threat of tariffs puts manufacturing production in Mexico at risk, potentially leading to massive layoffs, a fall in foreign direct investment (FDI), and stagnating economic growth.

FDI may already be taking a hit. Blue chip Japanese companies have warned more than once that the on-off threats of tariffs is making them think twice about investing any more in Mexico.

The Japan External Trade Organization, or Jetro, a government-related organization that works to promote mutual trade and investment between Japan and the rest of the world, said that four major Japanese investments in Mexico have already been halted due to the reigning uncertainty. Three major Japanese car manufacturers, Nissan, Mazda and Honda, have even threatened to pull out of Mexico altogether.

The Waxing and Waning Whims of Donald J Trump

These cases underscore one of the biggest problems with Trump’s constant use of the threat of tariffs to get what he wants: the prolonged uncertainty it creates. Even if he keeps walking back those threats, Trump is still doing immense, if not fatal, damage to the USMCA trade deal by raising economic uncertainty to levels that many companies simply are not willing to bear. As the WSJ recently noted, Trump’s arbitrary and personalized policymaking is at odds with the predictability that businesses crave.

Trump could tamp down the anxiety by laying out a coherent agenda (as some advisers have attempted) and a process for implementing it, such as asking Congress to write new tariffs into law, as the Constitution stipulates.

But that isn’t his nature. He revels in the power to impose and remove tariffs and other measures without warning, process, checks or balances.

The result has been economic-policy uncertainty at levels seen in past shocks such as the 2001 terrorist attacks, the 2008-09 financial crisis and the onset of the Covid pandemic in 2020. Those were all driven by events beyond U.S. control. This one is man-made, and will wax and wane with that man’s word and actions.

The financial toll from Trump 2.0’s tariffs is already magnitudes higher than the impact from all the tariffs imposed by Trump’s first administration. According to the FT, the first Trump administration imposed levies on imports valued at around $380 billion in 2018 and 2019. The new tariffs already affect $1 trillion worth of imports, estimates the Tax Foundation think-tank, rising to $1.4 trillion assuming exemptions covering some goods from Canada and Mexico expire on April 2, as was initially indicated.

When the reciprocal tariffs kick in on April 2, assuming they actually do, Mexico should, in principle, be less affected than other countries since: a) it has a trade agreement with the US; and b) unlike Canada and the EU, Mexico has opted not to impose retaliatory tariffs on US goods. But Trump’s tariffs are driven not just by economic considerations but also other issues such as the amount of progress Mexico is deemed to be making on containing immigration and executing the US’ whimsical demands vís-a-vís the drug cartels.

Deportation and Remittances

Mexico also faces other risks, including the prospect of the US dumping millions of deported LatAm immigrants at its southern border. If Trump carries through on this threat, it will impose a massive social-welfare overhead on Mexico’s economy. The mass deportation of Mexican immigrants will also deprive Mexican families, and the broader economy, of some of the much-needed money remitted by workers who send what they can afford back to their families. In 2024 alone, Mexico received $64.7 billion in remittances — equivalent to 3.4% of GDP.

In some Latin American and Caribbean countries, remittances represent an even larger lifeline for the economy. They include Nicaragua, where they represent 27.2% of GDP, Honduras (25.2%), El Salvador (23.5%), Guatemala (19.6%), Haiti (18.7%) and Jamaica (17.9%). Deporting immigrants en masse will remove a substantial source of revenue that has been supporting the exchange rates of these countries’ currencies vis-à-vis the dollar.

This, together constant threat of US tariffs is not just causing (potentially irreparable) harm to the USMCA trade deal; it is also, as Michael Hudson warned a few weeks ago, threatening to “radically unbalance the balance of payments and exchange rates throughout the world, making a financial rupture inevitable.”

So far, the Mexican peso has withstood the vagaries of Trump 2.0’s economic policy surprising well, and is actually slightly stronger than it was when Trump returned to the White House on Jan 20. The currency is up 2.4% against the dollar so far this month and 3.4% over the past three months. Analysts at Barclays attribute this, in part, to the cautious, largely non-confrontational approach that Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum has taken to handling the tariff issue.

There are also other factors that should work in Mexico’s favour. For example, as the Moody’s analysts note, the banking sector retains strong capital reserves and credit loss provisions, which should support its ability to absorb potential losses. That said, bank sector profitability is likely to decline due to rising provisioning needs.

Another potential fillip is the fact that the Bank of Mexico currently holds the highest level of foreign currency reserves on record ($235 billion). This is roughly three times higher than the reserves on hand during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

To put that in perspective, Canada, an economy roughly 10-15% larger than Mexico’s, has total reserves of just $121 billion. The UK’s $3.31 trillion economy is backed by even less (just $94 billion of reserves). However, stacked up against similarly sized emerging economies that have also suffered debt crises in recent decades, Mexico’s reserves look somewhat less impressive. Russia, for example, boasts foreign currency reserves of almost $700 billion while South Korea’s central bank has just over $400 billion at its disposal.

Whether Mexico’s reserves are enough to avert a full-fledged debt or banking crisis, we will hopefully never have to find out. You see, banking or debt crises in Mexico have an annoying habit of spreading to other countries and other banking sectors. When, in August 1982, Mexico’s then-Finance Minister, Jesús Silva-Herzog, declared that Mexico was defaulting on its dollar-denominated tesobono bonds, it sparked the beginning of the Latin American debt crisis.

After years of surging interest rates, declining global trade and falling commodity prices, LatAm economies that had borrowed heavily on the international debt markets suddenly reached a point where their foreign debt exceeded their earning power. The result? A domino chain of defaults. The IMF came swooping in with bailouts and structural adjustment programs, setting off Latin America’s Decada Perdida (Lost Decade) as investment that might have been used for development or to combat poverty was instead used to pay back the IMF.

The real beneficiaries of the bailouts were, of course, global banks, mainly based on Wall Street. They were essentially brought bank from the brink of collapse by the recycled loans the IMF made to Latin American countries, which were then used to pay off the debts to Wall Street, albeit with a haircut or two. As Nicholas Taleb notes in his book Black Swan, the losses that bankers in the US had accumulated on their LatAm bets had been catastrophic, perhaps more than the banking industry’s entire collective profits since the nation’s founding in the late 1700s.

It was a similar story in the Tequila Crisis of 1994, which arguably served as a prelude to the sovereign debt crises later than decade. Once again, hot money poured into Mexico to take advantage of the country’s comparatively higher interest rates and bullish investment returns. This speculative rush created its own momentum. The more investors shifted dollars south, the higher Mexican stocks climbed and the easier it became for Mexican companies and their government to borrow seemingly endless sums of dollars.

But by 1994, a confluence of political forces (most notably, the Zapatista’s short-lived revolution in the southern state of Chiapas and the assassination of the presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio) and financial risks (most notably, market fears of a devaluation of the peso, which eventually materialised in December 2024) triggered a stampede of hot money out of the country, leaving Wall Street banks once again heavily exposed.

As I wrote in my 2013 article for WOLF STREET, “The Tequila Crisis: The Prelude to Europe’s Economic Storm”, the Clinton Administration, clearly panicked by the potential ramifications of the Tequila Crisis for US banks, quickly assembled a huge package of funds, ostensibly to bail out the Mexican financial system:

After all, it was the least it could do to help its struggling neighbour. The fact that Clinton’s then Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin was also a former co-chairman of Goldman Sachs, the vampire squid of recent lore, which just so happened to have aggressively carved out a niche for itself in emerging markets, especially Mexico, is obviously mere coincidence.

According to a 1995 edition of Multinational Monitor, Mexico was “first and foremost among Goldman Sachs’ emerging market clients since Rubin personally lobbied former Mexican President Carlos Salinas de Gortari to allow Goldman to handle the privatization of Teléfonos de México. Rubin got Goldman the contract to handle this $2.3 billion global public offering in 1990. Goldman then handled what was Mexico’s largest initial public stock offering, that of the massive private television company Grupo Televisa.”

But it wasn’t just the US government that seemed determined to lend a helping hand to Mexico’s banks and, indirectly, their all-important creditors. The IMF also extended a package worth over 17 billion dollars – three and a half times bigger than its largest ever loan to date. The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) – the central bankers’ central bank – also got in on the act, chipping in an additional 10 billion dollars.

With such vast sums flowing in and out of Mexico, one can’t help but wonder where the money went and who ended up having to pay for it. In answer to the first question, Lawrence Kudlow, economics editor of the conservative National Review magazine, asserted in sworn testimony to congress that the beneficiaries were neither the Mexican peso nor the Mexican economy:

“It is a bailout of U.S. banks, brokerage firms, pension funds and insurance companies who own short-term Mexican debt, including roughly $16 billion of dollar-denominated tesobonos and about $2.5 billion of peso-denominated Treasury bills (cetes).”

Fast-forward to today, if, heavens forbid, something similar were to happen, it is safe to assume that any resulting contagion would spread to other countries and banks in the region, quite possibly triggering a generalised debt crisis. As Yves pointed out in her preamble to the Hudson piece mentioned above, banks’ dollar funding costs would spike, leaving them unable to roll over maturing dollar debts, which would result in insolvency.

But there is a major difference between the banking sector in Mexico today and during the Tequila Crisis: today, almost all of the big lenders are owned by foreign banks that essentially bought up almost the entire sector for cents on the dollar after the Tequila Crisis. Of the six largest banks, only one, Banorte, is Mexican, according to El Financiero. The other five are subsidiaries owned by (in descending order of importance): Spain’s two largest banking groups, BBVA (#1) and Santander (#2), Citi (#3), Scotiabank (#5) and HSBC (#6).

This newish state of affairs is a hangover (pun intended) from the Tequila Crisis. One of the conditions of the bailout of Mexico’s banks — which, by the way, Mexican taxpayers are still paying for today — was the sell-off of its largest commercial banks to foreign lenders. As a result, this time round it is not just US banks that would be heavily exposed to the resulting fallout of a full-fledged banking crisis in Mexico; so, too, would European lenders.

And it would be Spain’s BBVA that would be the main vector of contagion. In fact, in 2017 the IMF warned in an assessment of Spain’s financial sector that the significant international presence of the country’s biggest banks, while providing welcome diversification effects after Europe’s sovereign debt and banking crises, may also have significant implications for inward and outward spillovers:

The share of financial assets abroad has grown continuously for the Spanish banking sector, with the largest international exposures by financial assets concentrated in the United Kingdom, the United States, Brazil, Mexico, Turkey and Chile.

Two years later, UBS alerted that Spanish banks’ outsized exposure to Latin American markets could serve as a source of contagion for future crises: according to the the Swiss lender, 80% of the Eurozone’s total banking exposure to the region was channelled through Spain whose banks have around €384 billion of counterparty claims in the region.

A “shock” in emerging and developing markets could also drag down the Eurozone economy, UBS warned. In 2019, Spanish banks’ exposure to Latin America was equivalent to around 30% of Spain’s GDP, leaving both the country and the Eurozone susceptible to contagion effects from a crisis emerging in any of the major contingent economies, the authors of the report, Themis Themistocleous and Ricardo García, warned.

In the case of BBVA’s exposure to and dependence on Mexico, it has done nothing but grow since then. The Spanish bank recently displaced Citi to become the largest lender to corporations both in Mexico and across Latin America. In the first three quarters of 2024, BBVA’s Mexican operations accounted for a whopping 55% of the group’s global net profits. It is also trying to expand its operations in Chile and Brazil, two markets in the region where it has much smaller market share.

Across Latin America, from Argentina and Chile to Peru and Colombia, Spanish banks are far and away the most invested. In fact, it’s no overstatement to say that as goes Latin America so goeth Spain’s banking system, and with it the EU’s.

Meanwhile, Mexico’s President Claudia Sheinbaum insists that Mexico’s economy is “doing very well” from a fiscal perspective while also (somewhat ominously) recalling that the country has a $50 billion credit line with the IMF, if ever, ahem, needed. She also criticised the structural conditions imposed by the IMF and World Bank in bailouts past, in particular their demands for sharp cuts to public spending on health and education and the privatization of state-owned industries. That will not happen under her government, she insisted.

If we were to need a loan from the Fund, we would never be accepting those conditions, because it would be renouncing what we are.

On the other hand…NPR – Moodys – Russia’s credit rating is cut to junk, and the dollar hits a new high vs. the ruble March 3, 2022 Well, perhaps things are no longer as we in The Western finance bubble say so, because we say so, any longer.

I’m afraid that this sort of article gets my back fur up simply because I cannot help wonder if this was Moodys giving an honest financial opinion or whether they are doing this to put pressure on Mexico to adopt Wall Street friendly policies. And I have read articles in the past how the US government uses the big credit rating agencies to downgrade the ratings of countries for countries that they do not like. Like the US dollar, they have long ago been weaponized so those predictions must be taken with a shaker of salt. Even if none of this is true, it has not escaped my notice how all those credit rating agencies like Moodys were giving triple-A ratings to mortgage backed securities which were found later to be nothing but dog ****. Excuse the rant but you may have noticed that the credit rating agencies are not on my Christmas card list.

The more WallStreet and finance Unfriendly policies Mexico embraces, the better it’s economy will become for its people. There I said it. I spoke the truth. Will DOGE and/or The Blob be coming for me now? (of course not I’m insignificant)

You make a good point, Rev Kev. The article does need a disclaimer, for which purpose I decided to use a wee excerpt from your rant. Hat-tip included. Gracias.

Thank you, Nick.

Great article Nick!

This was really when the landslide against the Peso took place ending up @ 3,300 Pesos to the $ in 1992.

When I was a teenager the exchange rate was a rock solid 12.5 Pesos to the $.

Imagine your savings having 1/264th the buying power against the almighty buck and most every other currency after the lost decade?

It coincides perfectly with the upswell in Mexican immigrants to the USA, why work in the Estados Unidos for nothing when you can support your family working in the United States?

I think the economy is doing well enough down here to weather the US threat (the Peso is certainly continuing to crush the Canadian dollar!), and my Mexican friends and neighbours are mad as hell as opposed to intimidated — they have after all been through this before and never in this position of strength. They seem determined to forge stronger relationships with Canada, the rest of Latin America, Europe, China, Russia; there is a lot of talk about BRICS, and much enthusiastic speculation about Claudia Sheinbaum’s upcoming meeting with Lula; I just learned that my neighbour has decided to add certification in Portuguese to her current English and Spanish teaching credentials.

Anecdotally, my business-class seat mate on a recent flight, a very successful Mexican professional whose STEM professional daughters and their families live in Vancouver, described the US as “just a place you have to fly over”.