Yves here. Oddly, this useful post entirely omitted the words “monopoly” and “oligopoly”. Is there some weird code of omerta in Europe about their use? We’ve been able to see the evidence of excessive corporate pricing power for some time. One proof is in the US profit share of GDP. This has been running in the 11%-12% vicinity for some time, which is twice the level Warren Buffett deemed to be unsustainable in the early 2000s (6%). Another proof is so-called “greedflation” of recent years, of companies raising prices under the cover of price increases in other sector, as opposed to as the result of increases in the costs of their inputs.

An issue with anti-trust enforcement is that it can be hard to define the proper boundaries of a market (this is fiercely fought in litigation). Private equity is skilled at identifying niches where they can acquire a competitively advantaged position and push prices around. Consider dialysis centers. An anti-trust enforcer is not going to bother going after monopolization where it occurs, in many local markets (done by different owner/investors), even though it is not hard to grasp that a patient who needs dialysis in Los Angeles is not going to drive to La Jolla to get a better deal.

Some readers may regard this piece as dog bites man. IMHO, it’s useful to stress the bad effects of monopoly and pricing abuses beyond where the discussion too often halts: higher prices to customers.

By Giammario Impullitti, Professor of Economics University Of Nottingham and Pontus Rendahl, Professor Copenhagen Business School; Professor University Of Cambridge. Originally published at VoxEU

From the inception of economics as a discipline, questions of competition, growth, and the distribution of their benefits have been central concerns. Pioneers like Adam Smith and Karl Marx grappled with these issues, shaping our understanding of markets, wealth creation, and its distribution. These concerns remain at the forefront of modern advanced economies. In recent years, the rise of ‘superstar firms’ and the growing concentration of market power have become hot-button issues in economic policy debates.

From Washington to Brussels, policymakers are grappling with questions about why a handful of companies dominate entire industries (Autor et al. 2020, Eeckhout 2021, Philippon 2019); why productivity growth has slowed down (Gordon 2016); and why wealth inequality has reached levels not seen since the Gilded Age (Piketty 2014). These concerns are not just academic – they are central to the economic challenges of our time.

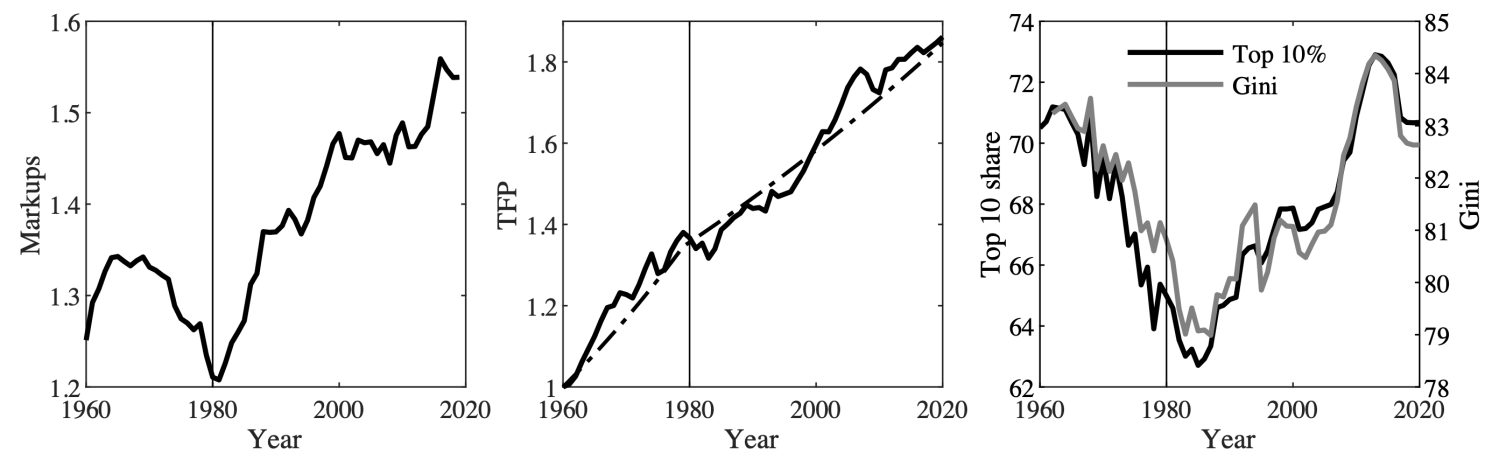

Concerns are particularly acute in the US, where market power has surged significantly since the early 1980s. Indeed, average markups increased from 20% to 55% by 2020. Meanwhile, productivity growth has stagnated, with total factor productivity slowing from 1.56% in the 1960–1980 period to just 0.77% in subsequent decades. This rise in market power and decline in productivity growth has coincided with a sharp increase in wealth inequality, as reflected in the growing share of wealth held by the top percentiles. These trends are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Market power, growth, and wealth inequality in the US

Sources: De Loecker et al. (2020), Fernald (2014), and World Inequality Database.

But what exactly is the link between market power, growth, and inequality? And why should policymakers care? In our recent research (Impullitti and Rendahl 2025), we provide a framework that ties these trends together, offering new insights into how market power shapes the economy.

Market Power and the Return Gap (r-g)

Piketty (2014) popularised the idea that wealth inequality is driven by the difference between the rate of return on assets and the growth rate of the economy, or the return gap, r-g. A higher return gap increases inequality as wealthier households, who own more assets, benefit from higher returns and save more, further increasing their wealth. Poorer households, who rely more on wages, see their incomes stagnate due to slower growth and higher markups. This dynamic deepens the divide between the rich and the poor, leading to a more unequal society.

How does market power affect the return on assets and the growth rate? To answer this question, we build a macroeconomic model where large firms invest in innovation to gain market shares and where aggregate innovation pushes overall productivity growth. Uninsurable income risk generates wealth heterogeneity across households.

We engineer a rise in markups as a response to an exogenous increase in the cost of entry for firms. 1 When barriers to entry rise, fewer firms compete in the market. This reduction in competition allows incumbent firms to charge higher markups, boosting their profits. Higher profits, in turn, increase the value of these firms, driving up returns and asset prices.

But reduced competition also affects innovation. Aggregate innovation (i.e. the sum of innovation from all firms) contributes to the economy’s overall stock of knowledge, which functions as a public good. Firms continuously learn from one another, fostering a cycle of innovation and progress. However, when competition declines, this knowledge-sharing process weakens. With fewer competitors, opportunities for exchanging ideas diminish, reducing the efficiency of innovation and ultimately slowing economic growth, g. This dynamic – where weaker competition stifles knowledge spillovers – creates a direct link between rising market power and declining innovation efficiency. 2

Finally, lower competition also conveys some bad news for labour income, both in the present and in the future. Higher markups create a wedge between the price of goods and the associated marginal costs: wages. As markups rise, real wages fall. Additionally, slower economic growth further exacerbates this outcome, dampening the prospects for future wage increases, which are closely tied to productivity growth.

The Return Gap and Wealth Inequality

Why does a rise in the return gap exacerbate wealth inequality? After all, if all agents have some wealth and are affected proportionally by a rise in the r-g differential, wealth inequality would be unaltered. 3 Our theory demonstrates that a widening return gap exacerbates inequality by affecting the saving behaviour of households in distinct ways across the wealth spectrum.

In our economy, uninsurable income risk implies that there are two reasons for saving: intertemporal substitution, and a precautionary motive (Aiyagari 1994). Poorer households, driven by the need to buffer against income risk, predominantly save for precautionary reasons, whereas richer households – having attained a high level of self-insurance – primarily save for intertemporal reasons. An increase in asset returns enhances the incentives for intertemporal substitution but has little impact on the precautionary motive. As a result, wealthier households respond more strongly to rising returns, increasing their savings at a higher rate than asset-poor households and further accumulating wealth.

Welfare Effect

Our research also sheds light on the welfare implications of rising market power. We find that the increase in markups and the slowdown in growth since 1980 have led to substantial welfare losses for most households. For the bottom 80% of the wealth distribution, these losses amount to roughly 34% of long-run consumption. In contrast, the top 1% of households have seen significant gains, with the top 0.1% experiencing a 30% increase in consumption.

Thus, while the rise in market power has benefited a small fraction of the population, it has come at a significant cost to the broader economy.

Conclusion

In the last four decades, advanced economies have witnessed a secular rise in both market power and inequality, as well as a slowdown in productivity growth. While these trends have happened concurrently, they may not have happened independently. Indeed, our research indicates that the rise in market power alone could have been a strong contributing factor to the rise in wealth inequality and the slowdown in productivity growth.

One takeaway from this intertwined nature of the above secular trends is that economic policies may have unintended consequences in domains where they do not directly operate, necessitating a multi-targeted approach for, for instance, competition policy. Given the role of market power in exacerbating wealth concentration, policymakers should rethink competition policy’s broader economic and social implications. 4 Stronger enforcement and pro-competitive reforms can help restore not only innovation and productivity but also a more equitable distribution of economic gains.

As policymakers grapple with these challenges, they must consider not only the immediate effects of their decisions, but also the long-term consequences for growth and inequality. By addressing the root causes of market power and its distributional effects, it may be possible to create a more prosperous and dynamic economy that also encompasses a more even distribution of both gains and losses.

Over the past four decades, the US has seen rising market power, slowing productivity growth, and deepening wealth inequality. This column explores how declining competition may be the common culprit. Weak competition lets dominant firms raise prices, suppress wages, and stifle innovation, thereby slowing economic growth. Meanwhile, higher asset returns benefit the wealthy, widening inequality by amplifying differences in savings behaviour. Rising markups drive stagnation and wealth concentration, underscoring the need for stronger competition policies to foster innovation, productivity, and fairer economic outcomes.

See original post for refereces

A free market fundamentalist might put forward the following counter-argument :

“A world without monopolies with pricing power is one lacking the excess free cash flows to invest into breakthrough innovation (which is expensive). The increasingly diminished role government plays in funding R&D creates a funding vacuum into which monopolies can pour their surplus cash to push forward the frontiers of innovation. Competitive markets with effective antitrust laws are antithetical to this because they naturally compress the margins of individual firms across the market, leaving no individual firm with the deep pockets required to invest into high risk, highly speculative ventures (eg the only way google can invest into the successful development of Alphafold is if they’re awash with money flowing from their dominance in search). Ergo, a world without monopolies is ultimately bad for consumers because it enables only incremental innovations (better mousetraps) and lacks the deep capital pools required for firms to play in the capital intensive domain of breakthrough innovation, especially with libertarian special interests successfully pushing governments out of picture vis a vis funding R&D.

The front end of innovation is also negatively impacted by draconian regulators waving the banner of antitrust while torpedoing an increasing number of M&A transactions. This discourages early stage funding into startups because investors want a reasonable prospect of exit liquidity to deploy their capital, and acquisitions by larger firms represent one of the primary mechanisms for returning said capital.”

This argument extolling the virtues of monopolies is one you may come across as you navigate the choppy waters of economic discourse in the age of neoliberalism.

e.g. from Peter Theil?

(Just asking because I haven’t bothered to look at what he says, but he’s more intellectual than the average oligarch and this sounds like a line he’d take.)

Thiel makes different but related points in his infamous “competition is for losers” argument. Eg he says highly competitive markets have “race to the bottom” price wars where firms continuously lower prices to compete for market share, which ultimately hurts consumers by lowering the quality of products. The counter-argument I present above is one I synthesized from views on markets, innovation and competition articulated by various free market absolutists over the years.

Is this not the counter-argument? Iron sharpens iron, etc? When you let the sword rust you just become Microsoft building crappier mousetraps.

Correction: Profit margins used to be about 12%…back in the goods old 2010s. Now they’re about 18%, and rising.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/A466RD3Q052SBEA

I have been amazed at how little this fact has been acknowledged, certainly in the corporate media, but also at economics blogs.

No, that is a different measure entirely. Excludes non-financial corps too. Profit share of GDP is not “profit margin” which is a revenue measure.

Sorry, the link was NOT profit share of GDP. It is “ Profit per unit of real gross value added of nonfinancial corporate business: Corporate profits after tax with IVA and CCAdj” —profitability.

If you have a link of to a profitability measure of financial corporations, that would be great.

This column explores how declining competition may be the common culprit.

In my opinion -for what little it is worth – Rising asset prices should never be associated with productivity. I see rising asset prices as additions to overhead – so if productivity is measured, as appears to be, output minus input, then, an increased asset price input being an overhead cost ( just like tax goes to Gov and debt servicing and interest goes to private) input will lower productivity and also outpace workers abilities to make enough to live……..I guess in short – simplified – due to my lack of deep econospeak modeling and assorted dupery …

Inflating asset prices, stock buybacks, tax avoidance, debt servicing, monopoly gouging along with countless ‘tolls to trolls’, fees, commisions and penalties —– these collected fees are overhead charges upon the productive economy’s firms/people (hard working people) directly to the economy’s large firms/people, who by privalege and political corruption, entilte themselves to this enrichment.

So without consideration, where there ought to be consideration, the two types of firms 1) Overhead producing firms 2) Productive firms. You get the following macroeconomic model treating both as the same thing.

“To answer this question, we build a macroeconomic model where large firms invest in innovation to gain market shares and where aggregate innovation pushes overall productivity growth.”

Both types of firms do as quoted but, I contend (and invite critisism for my own edifiction), when one type of firm does it….it is an overall boost to overhead and when the other type of firm does it….it is an overall boost productivity. It just leads me to believe that “common culprit” adressed in this article is not the “common culprit”.. “Over the past four decades, the US has seen rising market power, slowing productivity growth, and deepening wealth inequality. This column explores how declining competition may be the common culprit.”

My “common culprit” is the over fourty years and many more years to boot. The common effort in knowledge and teaching, directed and made by the overhead producing sector, in effort to disapear themselves as an actually dicernable entity or firm type – a passive non-participant.

I come to this view by all the money spent to get their lackeys to do thier bidding.

It has been a bi-partisan direction for over fourty years.

The lack of the Dems to put forward any progressive legislation for 40+years and, to thwart anyone who may appear in earnest toward that end should put an end to their doubt. Of course, now the dems can fake how much they care.

But for sure, dems can’t be seen to be resposible for the shut down, because if they have any hope of comming back into majority without doing anything at all about “slowing productivity growth, and deepening wealth inequality” they sure as hell can’t be seen to lean that way – cause if they do they might need to act. Horrors

And, let it be clear that both parties are playing it out for themselves to be in the class of the new kings and courts…..let the peasants suffer for electing the other.