Yves here. This is a fascinating little study. While correlation is not causation, the finding makes a certain amount of sense. Shopping districts that have stores with character and the potential to serve as hubs of human interaction had a greater propensity to vote for the UK Independent Party. I am not sure how to determine whether the causality might run in the direction of areas less favored by big box retailers and national brands being economic backwaters, and it’s the backwater status that drives the much-maligned populism, as opposed to the loss of “social capital,” as this post posits. A similar drive could be that the gentrification-of-sorts depicted as a driver could similarly reflect the arrival of more affluent citizens (seeking cheaper housing?) who diluted the old local culture and have more mainstream voting patterns.

I’m not sure how well this theory generalizes to the US. Under Mayor Giuliani, New York City changed its commercial zoning laws to favor big-box stores, and the level of quirky, interesting stores declined markedly. While New York has enough small storefronts, particularly for restaurants, to still have a lot of street life, the change was still visible. By contrast, yours truly has visited Dallas a few times. Its strip malls, which in many US cities are the analogue to high streets, are so bland that it looks like all of them were put in place by at most 7 different developers, each using its own (single) designer/architect. And the even among those few formats, the color schemes are virtually identical: the blandest imaginable browns and beiges. This pattern existed before the mid 2010s additional influx of corporate workers from warmer climes and many big companies put more major operations in the Dallas areas, particularly Plano. Given the continuing blandness versus an influx of a very different population, it would be interested to see whether (if at all) voting patterns in the relevant districts changed. Other US cities may hew to the Dallas pattern.

By Stephane Wolton, Samira Gasimova, Ricardo Paccioretti, and Giuseppe Palladino. Originally published at VoxEU

Independent shops and services lining high streets across the UK serve more than a commercial function. This column studies how different types of commercial spaces – from garages and convenience stores to pubs and bookshops – affected the electoral fortunes of the UK Independent Party from 2011 to 2019. The findings suggest that a decrease in independent consumer outlets yielded an increase in UKIP’s vote share for that postcode, while ‘branded’ consumer outlets had no such effect. The corresponding loss of social capital in communities where these venues disappear is a plausible mechanism behind these results

Have you ever entered an outlet that looks like more than merely a place of business? The owner and/or some of the employees are local public figures. Regulars are greeted by their first names. Services (such as keeping keys) are provided to whomever needs them. The place is bursting with life, and each visit delivers its lot of entertainment. Serving as a social hub for weak ties and sidewalk acquaintances, it provides a short retreat from the stress of everyday life. If you know such an outlet, you are lucky to know a ‘third place’ (Oldenburg 1999), a spiritual tonic beyond home and work.

Third places can take many forms: cafés, bars, food stores, convenience stores, barbers, hairdressers, etc. They are often at the heart of a neighbourhood, literally and figuratively. Indeed, knowing about them is a mark of belonging to the local community. Sociologists have highlighted their importance in building ‘thin’ trust between locals (Oldenburg 1999 and Jacobs 1961 pre-eminently). Urban planners have stressed their vital role for a better city life (e.g. Gehl 2013, Moreno 2024). But until recently, economists and political scientists have been less aware of their social and political significance.

Fetzer et al. (2024) used survey data to measure the impact of shop vacancies in the UK on the intention to vote for the UK Independence Party (UKIP) – the main populist party in the country until its rebirth as the Brexit Party and then Reform UK – but attribute their findings to local economic decline rather than the social role played by these outlets. Also using survey data, Bolet (2021) examines how the closure of community pubs increases reported willingness to cast a ballot for UKIP. Davoine et al. (2020 in French, summarised in English in Algan et al. 2020) highlight a correlation between the disappearance of services and stores in a community and protest events by the ‘gilets jaunes’ in France.

In a recent paper (Wolton et al. 2024), we complement these works in multiple ways. We look at local election results over the period 2011–2019 in the UK, using geolocalised data on outlets at the postcode level (the smallest administrative unit) obtained from Point X. Our rich dataset contains more than 13.5 million outlet-year observations, which we aggregate at the ward level, the smallest unit for which electoral data are available. We use independent consumer outlets as a proxy for third places. Independent consumer outlets consist of eating and drinking establishments, legal and financial services, personal services, property services, and any retail shops not characterised as a ‘brand’ by Point X. We track how the evolution of these outlets in a ward over time affects support for UKIP. We further study how the effect of third places compares to the impact of branded consumer outlets and other outlets (B2B services, sport and entertainment, education and health services). We find that the presence of independent consumer outlets reduces the vote share for UKIP in local elections even after controlling for multiple economic and socio-demographic factors. Branded consumer outlets and other outlets have no effect on support for the populist party.

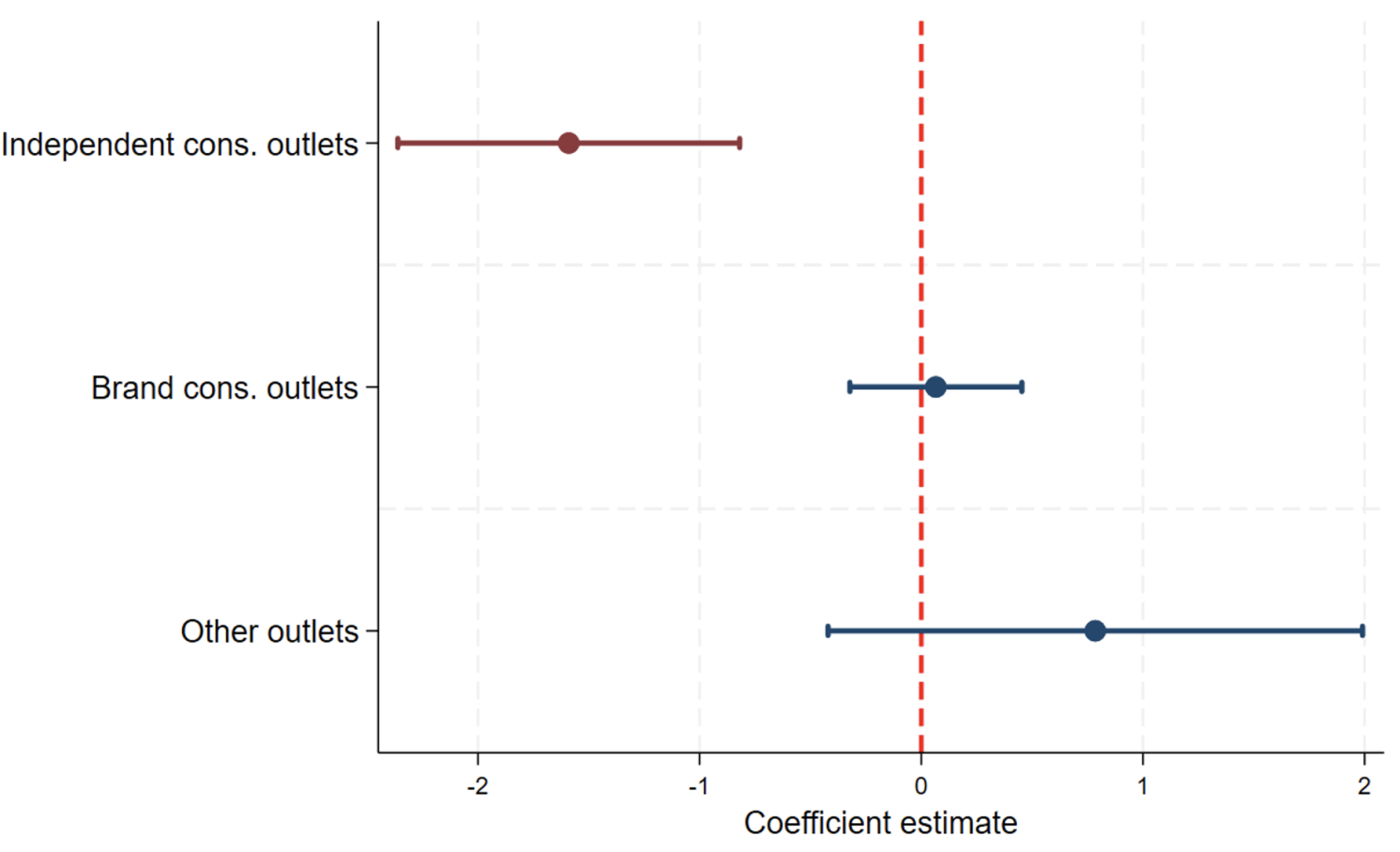

Figure 1 High street changes and UKIP support in local elections

Note: Figure plots the coefficients from a linear regression that includes controls for economic factors (e.g. house prices), socio-demographic factors (e.g. ethnic composition), ward fixed effects, and local authority year fixed effects (as each ward is nested in one local authority).

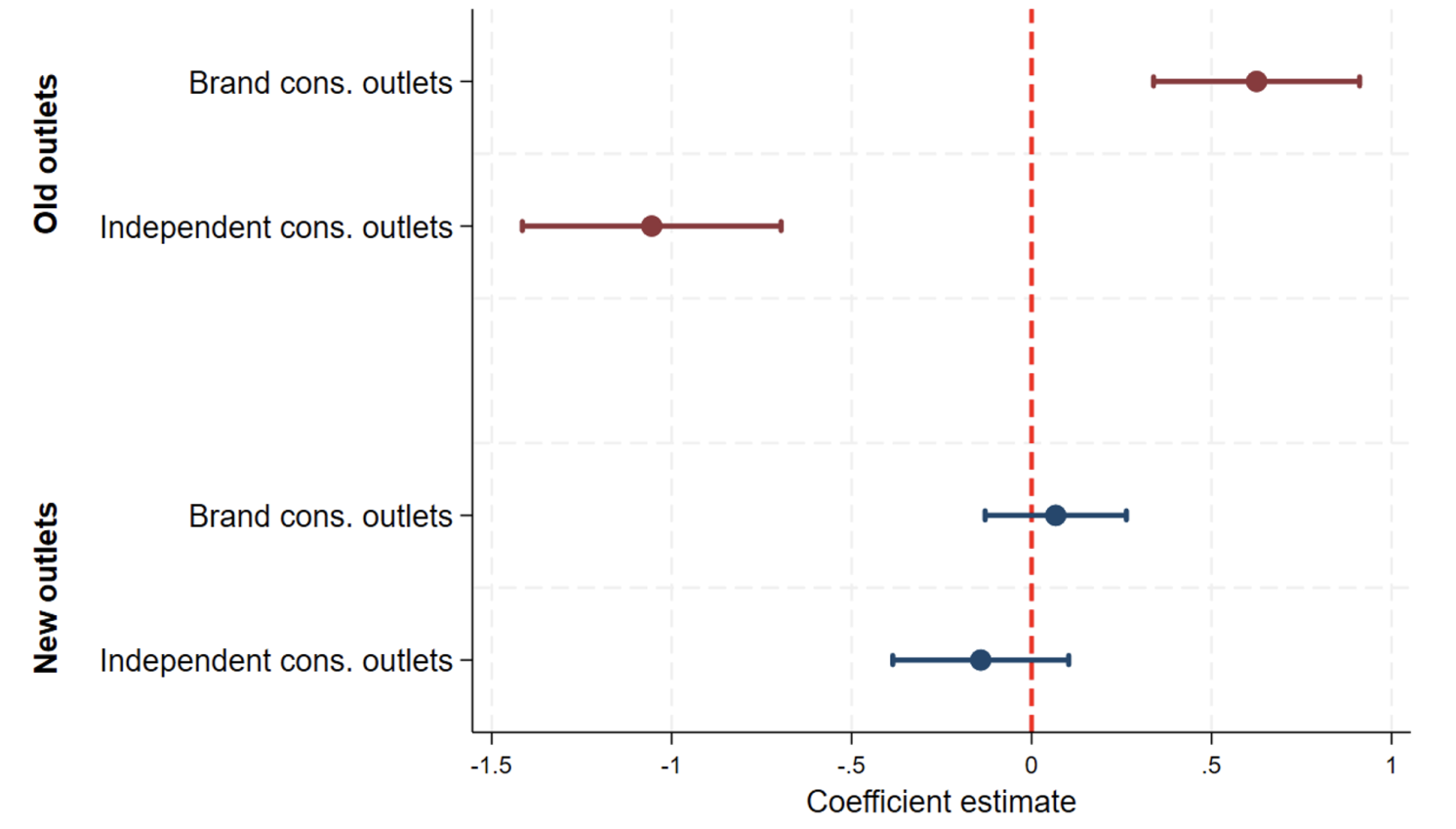

Is this enough to recover the political consequences of third places? Probably not. Despite our multiple controls, part of the effect we obtain may be due to local areas thriving or suffering economically. Yet, a series of additional tests suggest that economic circumstances are unlikely to fully explain the impact of independent consumer outlets on populist vote share. The data we have allow us to separate between old outlets (present in a local area for more than a year) and new outlets (less than a year old). If the economy is the key factor, old and new independent consumer outlets should have the same electoral consequences. Our analysis suggests that only the presence of old independent consumer outlets reduces the vote share for UKIP.

Figure 2 Old and new outlets and the support for UKIP

Note: Figure plots the coefficients from a linear regression that includes controls for other outlets, economic factors (e.g. house prices), socio-demographic factors (e.g. ethnic composition), ward fixed effects, and local authority year fixed effects (as each ward is nested in one local authority).

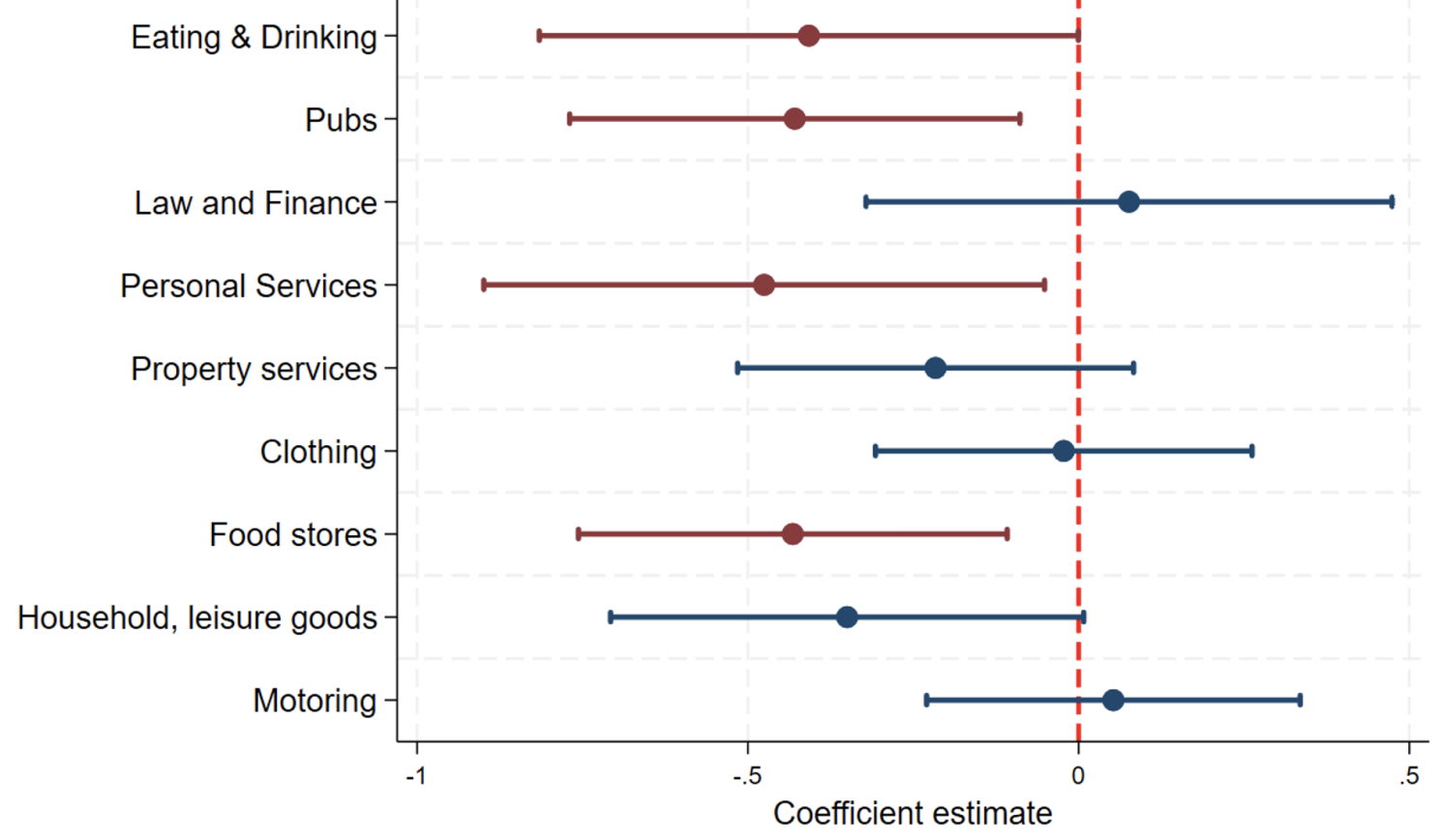

We go even further. When building our measure of independent consumer outlets, we grouped together very different types of commercial places: personal services with property services, convenience stores with garages. Arguably, some of those business categories serve more of a social function than others, especially drinking and eating places, personal services (e.g. barbers), household goods stores (e.g. bookstores), and food stores. We show that those social outlets are the ones driving our main results: their presence negatively correlates with populist success.

Figure 3 Independent consumer outlet types and support for UKIP

Note: Figure plots the coefficients from separate linear regressions, each including controls for brand outlets of the same category, other outlets (including other consumer outlets), economic factors (e.g. house prices), socio-demographic factors (e.g. ethnic composition), ward fixed effects, and local authority year fixed effects (as each ward is nested in one local authority).

Beyond the effect of immigration and globalisation (Docquier et al. 2024, Ottaviano et al. 2021), beyond the effect of terrorism (Sabet et al. 2023), and beyond the effect of economic shocks (Sonno et al. 2022) and austerity (Klein et al. 2022), our work highlights a new channel through which populists gain traction. The mechanisms we uncover are distinct from previous works. Indeed, this is not a ‘left-behind’ phenomenon. Urban, middle-class, young areas are the most reactive to change in their high streets, as we show in the paper. As such, our findings highlight how populism spreads through all strata of society.

What can be done about it? Governments and local authorities often put in place policies to revitalise the high street. Yet, to build a real local community – or at least, a sense of communality – it is not enough to just fill the space. Pop-up shops by their transient nature will fail to revive an area. Branded consumer outlets may hurt rather than help. It is important to identify outlets that will serve as focal points and local figures who will invest socially in their local area. ‘One size fits all’ policies will not work. In this sense, the UK government’s new policy giving more power to local councils to auction off leases for commercial properties that have been empty for long periods is a welcome step (HM Government 2024). Moving forward, our work provides an argument for subsidising third places given the positive externality they generate within their neighbourhoods.

See original post for references

This reminds me of an unofficial policy of one local government in the UK I had dealings with in the 1990’s. They were buying up the many abandoned pubs in urban areas and promptly demolishing them. The unstated policy was to prevent the National Front (at the time, the main fascist party) from buying them and turning them into de facto local community centres. From the days of football hooliganism, certain pubs in Britain had operated in many communities as centres for far right activity. Pubs often had an unstated role in local politics – in Ireland, certain pubs would be associated with one of various republican/left splinter groups. It wasn’t unknown for people to get shot just for choosing the wrong place for a pint.

As Yves points out with this article, there are many causality issues in interpreting the data on shop closures, not least that some corporate outlets – including the likes of McDonalds or chain coffee houses – can act as informal community hubs, while local businesses can often be quite hostile to anyone who isn’t spending lots of money. In parts of Asia, in small towns the local 7-eleven can be a sort of hub where everyone meets up in the absence of other places where people meet. In the Japanese anime ‘Your Name’, there is a funny (and probably truthful) scene in a small town where some teenagers are excited to go visit the new cafe in town as they are desperate for somewhere interesting to go. Turns out its a park bench with a Boss Coffee vending machine next to it. But they still enjoy it.

An additional complication is the cause of commercial decline. Lots of High/Main streets decline because of economic decay, but others are simply because they’ve been displaced by a better/nicer one, a local mall, or the local government just let too many cars drive too it so people prefer to go somewhere else. The quality of local government really does matter (I think the phenomenon of local mayors makes a huge difference in protecting small towns and villages in France and some other European countries) – but there is only so much you can do when it comes to protecting local businesses. So many ‘nice’ businesses – the local bakery or cafe – are more labours of love than real businesses.

Thanks. I agree on the complexity of cause and effect. Thus I am doomed to fall back upon anecdata and (sorry, yet again) my own Ward in one of the “most marginal seats” in the UK.

In my council ward, the closest “suburban high street” was “posh” when I was a kid. Now most shops are vacant and it’s becoming a hub for crime and will almost certainly start kicking out all its Labour councillors in May and possibly the MP for the wider parliamentary seat in 2029ish since this suburb is “the hub”. The BNP last put up a candidate in the 1990s. Now Reform is back with a vengeance. Yet there is another suburb (Mapperley Top) that I have to regularly go through and I see few boarded up premises. There is increased turnover in shops. but they don’t stay vacant for long. It is now the “posh” bit. I’ll be watching the 2025 Nottinghamshire election results very carefully to see how the “Gedling parliamentary constituency” is breaking further apart internally into the “haves” and “have-nots” or the “posh suburbs” and “no-longer-posh-suburbs”. Stuff is going on.

I have suspicions this is all due to the terrible levels of central government funding that has led so many councils to bankruptcy. Gedling Borough Council very obviously prioritised areas where its Labour councillors lived/worked (like where I live, an island in an otherwise ocean of socioeconomic poverty) and Mapperley Top (where most of the local Labour Party live). Now the pinch is getting so severe we are all suffering.

One sad little PS for you PK. Our local Boots Chemist now has security guard. A year ago (last time I entered the place) I asked where the male staff were. “All quit due to threats of violence”. What about x (the main Pharmacist, lovely Irish gay guy)? “Traumatised when the length of the queue caused heart failure in a customer. He spent half an hour doing CPR til ambulance arrived. Customer died. He quit and has moved back to Ireland.” We are totally family blogged.

Sounds pretty grim.

I was reading a local history of a local town centre in Dublin (Dun Laoighaire, just to the south) and in the 1950’s the Main Street had a system where a housewife could call up (for example), the butcher, order her sausages and chops, and then add in a request for apples and some 3 inch screws. A delivery boy on a bike would then be dispatched from the butcher, and would pick up the apples from the greengrocers and screws from the local hardware store, and be at the customers doorstep within an hour. Beat that Amazon! This fell apart first off all from the assault from supermarkets in the 1960’s, and then a combination of a huge shopping centre 20 mins drive away plus online shopping has killed this street off. Despite multiple investments from the local council (seems to be a new initiative very few years), its more or less fallen apart, with just a few interesting new restaurants and ethnic shops to pull it together. And this is in a very prosperous side of the city.

There are multiple reasons why one street can thrive while another fails – and it’s not always down to money. The whims and needs of landlords (and their funding banks), fire regulations (making it unviable to use upper storeys), car oriented transport policies, too many out of town shopping centres, and so on, have been enormously destructive. Even in France, with their (still) wonderful local town centres, they’ve done enormous damage by allowing car oriented shops everywhere.

But what you describing really does sound like deep economic decline, along with official neglect. One small town I know more than I’d like – Holyhead in Wales (because of regular stops due to various ferry delays), is a good example. The town was founded by Romans, thrived due to its position on the Ireland to England route, then declined due to the loss of a major employer (local nuclear plant), and of course ro-ro ferries and Brexit kicked it even more. It has a fairly pretty Main Street, what looks like having been a very expensive pedestrian bridge linking it to the port, but it’s a very sad picture, with lots of dead eyed people hanging around. Some locals have started up a nice little cafe, which seems the only hang out for younger people with a bit of money. Everywhere else is just grim (including the usually empty pubs).

I can corroborate to a tee what you say about Dun Laoighaire. Why? Cause my mum’s closest cousin grew up there! Mum used to hang around with her when growing up. The cousin is now in assisted living some way from the centre (which, if I understand correctly, she’d not want to visit). Nobody wants to go to Dun Laoighaire. You get transport from there and that’s it.

Yeah I sense official neglect around here. Dad was pulling his hair out for a week jumping through hoops to satisfy fire safety inspections of his factory (which was tip-top condition). I sense landlords are a problem round here. I confess I’m not completely up on the modern complexities of Land Value Taxation (LVT) but if they can tax the land appropriately then I can’t help but think that our local town centre would be snapped up pronto and get new business there.

For decades, the implementation of Euclidian Zoning in the US argued against the accumulation of much “social capital.” The separation of commercial and residential land uses created mono-use, low social interaction wastelands. Along with the widespread adoption of the automobile social fragmentation became the norm. Of course this was a bonanza for developers who didn’t have to spend a lot of time thinking about what and where to build.

This began to change in the 1990’s with the advent of the New Urbanism and Smart Growth movement among planners.

However, developers and bankers only demonstrated enthusiasm for mixing commercial and residential land uses when there was a large public subsidy at hand. A leading New Urbanist once told me that bankers had a template of 16 land development types that they would fund, and none of these development types included things like walkable communities, limited parking, mixed uses and limitations on automobiles. This was commie thinking.

Anyway, IMO there may be lots of alienation out there, but there is not much social capital to destroy in the vast desert that is suburban, strip mall America.

So much of what makes or breaks cities can come down to quite minor changes in zoning and building regulations. The urban theorist Alfred Twu has some very interesting comparative studies in how this has resulted in very different forms of development in the US, China and Japan. I’d add South Korea to the list – it has a regulatory context quite similar to the US and Japan (the Japanese borrowed their zoning ordnances from the US in the 1920’s, and then left them for the South Koreans in the post war years), but with a few tweaks the result is entirely different urban forms. Add to the list land use patterns (Japanese cities essentially follow the pattern of rice fields), and you end up with vastly different cities.

Japan consciously favours a laissez-faire attitude to small commercial units, which results in far more small businesses scattered around urban areas. Plus, there is no default right to park on any public highway, which makes a huge difference.

Japan consciously favours a laissez-faire attitude to small commercial units, which results in far more small businesses scattered around urban areas. Plus, there is no default right to park on any public highway, which makes a huge difference.