Yves here. This post goes carefully through ownership and trends in holding of Treasuries. It concludes that official holders, as in governments, look likely to further reduce their stakes, but that this ironically does not mean the demise of the dollar as reserve currency, at least in the near to intermediate term.

This post also helps correct a misperception that seems widespread among readers: that foreign governments are the main buyers of Treasuries. US investors have been and remain the dominant holders.

By Paola Subacchi, Professor of Political Economy University Of Bologna and Paul van den Noord, Affiliate Member, Amsterdam School of Economics University Of Amsterdam. Originally published at VoxEU

The trade war launched by the Trump administration follows a longer-term pattern of geo-economic fragmentation, but it dwarfs all prior expectations. This column looks beyond the trade war, asking if, in a more fragmented global economy, official investors should continue to hold US federal debt to the same extent as before. The answer is likely no, due to the increasing exchange rate risk on this debt as global trade stalls. Yet this does not imply the demise of the dollar as the global reserve currency, unless economic rationale fails to win precedence over brinkmanship.

For more than a decade, numerous factors have been pushing the world economy towards geo-economic fragmentation in response to disruptions in supply chains and security considerations (Boeckelman et al. 2024), automation (Faber et al 2025), China’s policy to intensify trade with the African continent (Amedolagine et al 2024), and the deepening of the European Single Market (Panon et al. 2025, Arjona and Revoltella 2024).

The trade war launched by the Trump administration fits in this longer-term tendency, but it dwarfs all prior expectations (Grzana and Ilzetski 2025) and will only have losers (Eiffinger 2025). A new status quo is likely to emerge from negotiations (Anil 2025), but the transition will be painful (Bertoldi and Buti 2025), as economic growth is set to stall with weaker competition and specialisation (Bombardini et al. 2025, Moro and Nispi Landi 2025). Moreover, the loss of diversification benefits of global integration may lead to more macroeconomic volatility (Attinasi and Mancini 2025).

The trade war seems to be motivated by the inequalities that may have resulted from the dollar’s reserve currency status (Monteiro and Piermartini 2024). Meanwhile the US administration is downplaying its benefits for the safe asset status of US Treasuries (Choi et al. 2024, Subacchi and Van den Noord 2023), even if this has helped to finance US defence expenditure on favourable terms (Yared 2024). Claims that tariff revenues will offset the loss of this fiscal advantage look groundless (Evenett and Fritz 2025).

With the global economy headed for more geoeconomic fragmentation, we use a three-country dynamic general equilibrium model built around stylised representations of the US, the euro area, and China to examine what this might imply for the global demand for US federal debt as the main reserve asset.

Who Holds Treasuries?

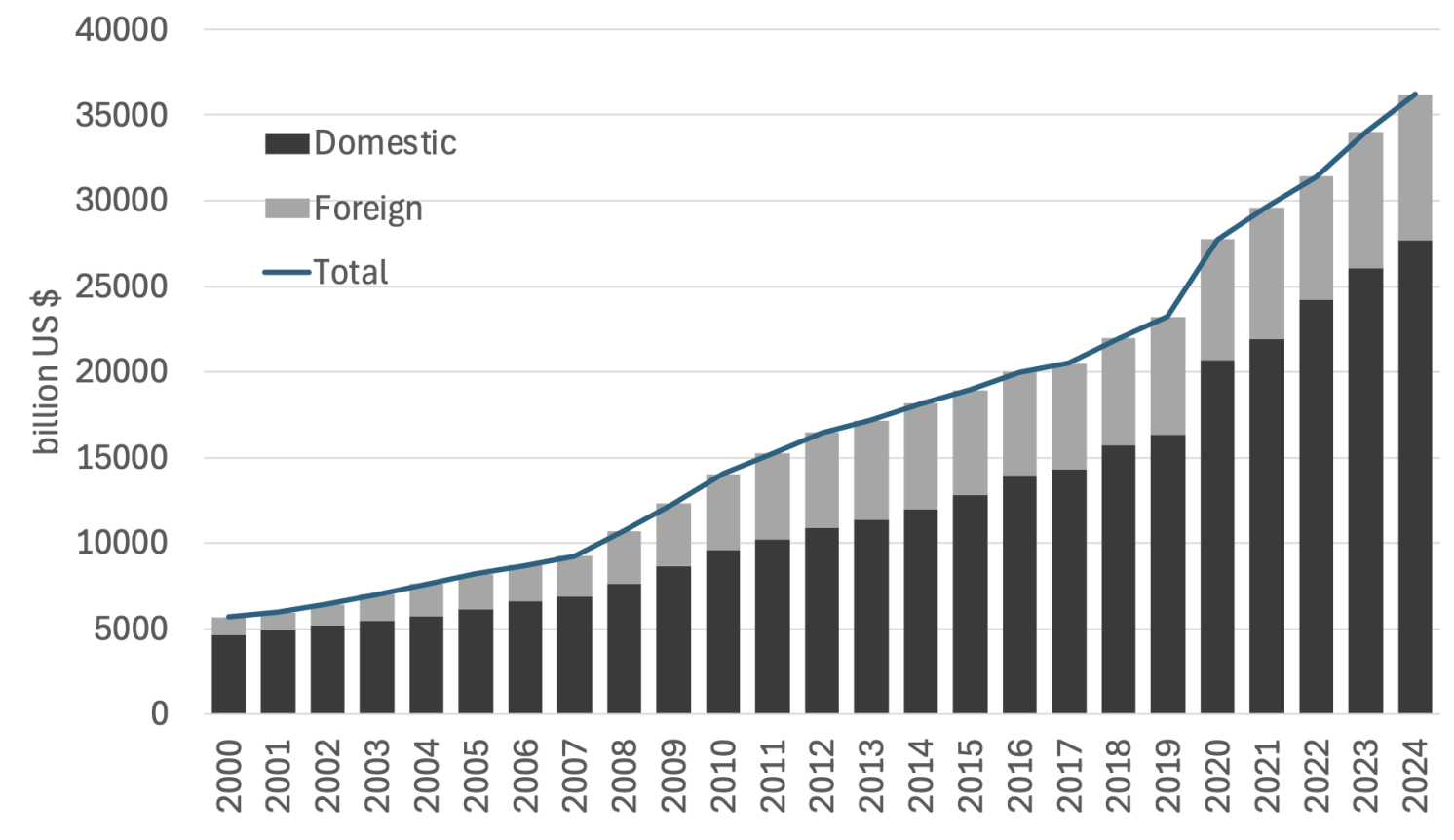

The world has accumulated large international dollar reserves, mainly invested in US Treasury Bonds (Figure 1). Around one-quarter of US federal debt (of over 120% of US GDP) is funded abroad owing to its safe asset status and being dollar-denominated.

Figure 1 Foreign and domestic holdings of US federal debt

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

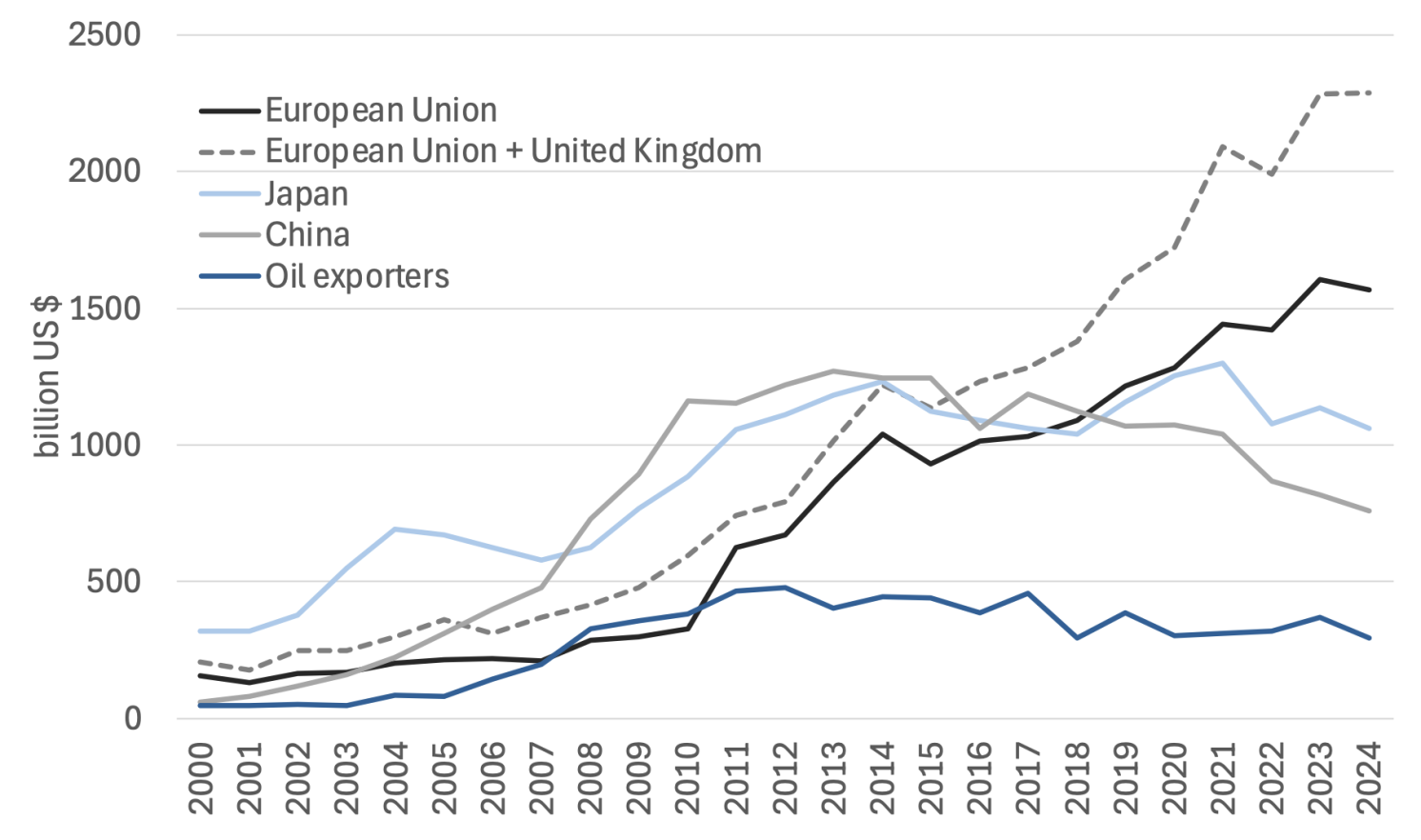

Figure 2 Foreign holdings of US federal debt by country or jurisdiction

Source: US Department of the Treasury. The jurisdictions included in this figure are the five largest investors in US Federal debt. The bulk of the EU holdings of US several debt are reported by its main financial centres, i.e. Ireland, Luxembourg and Belgium (where SWIFT and Euroclear are established).

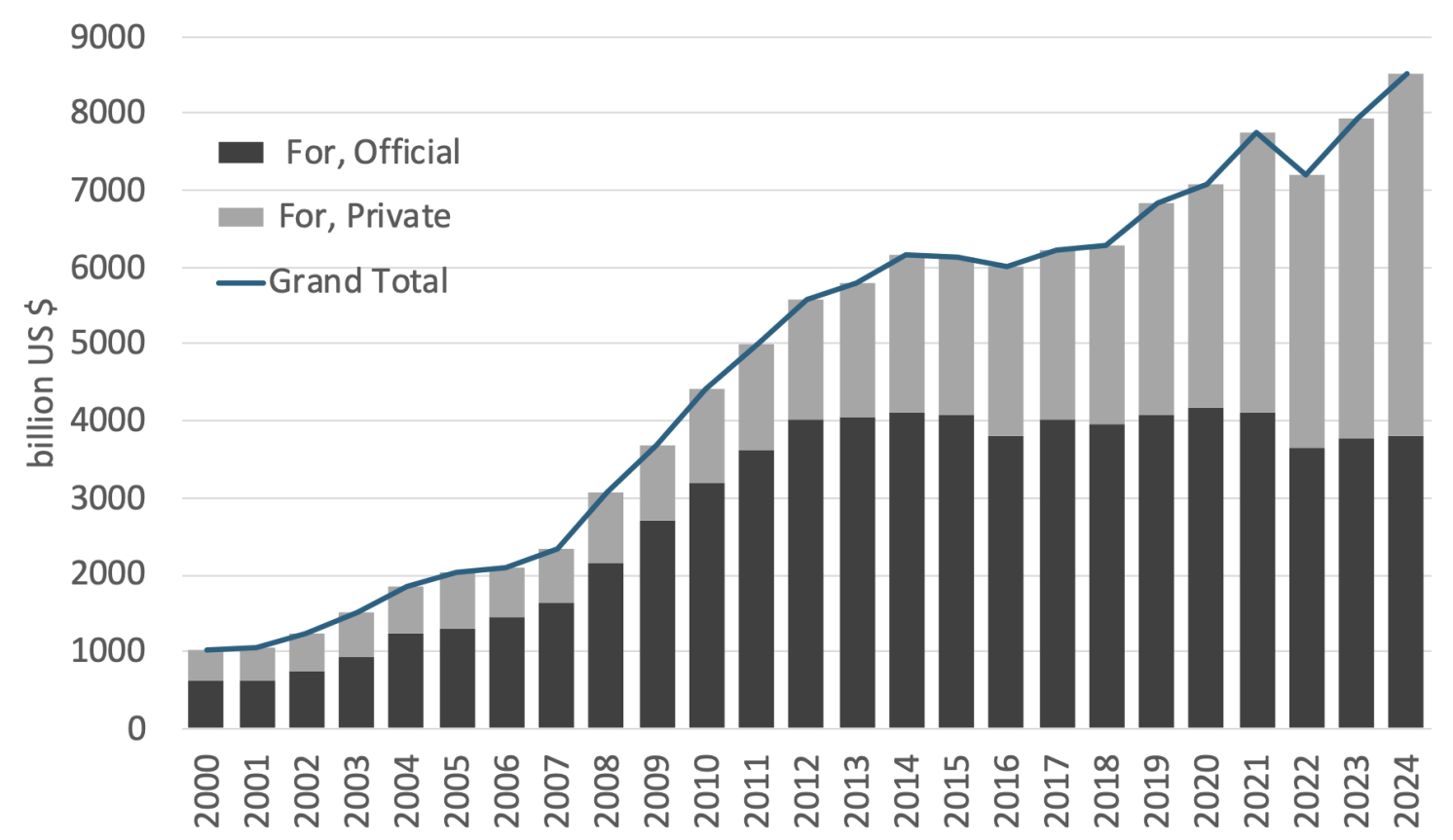

Figure 3 Official and private foreign holdings of US federal debt

Source: US Department of the Treasury.

In past decades, China and Japan have been the largest holders of such debt (Figure 2). However, weak returns on US debt following the Global Financial Crisis and geopolitical considerations, including sanctions on Russia’s dollar reserves, have prompted China to reduce its Treasury holdings in favour of other currencies and gold (Ahmed and Rebucci 2025, Aiyar and Ilyina 2023, Eichengreen 2023, Laser et al. 2024). While this affects most developing countries (Bordo and McCauley 2025), the portfolio shift in China is systemic.

EU member states and the UK have picked up the slack so far. Their increased demand for US Treasuries is mainly private, while official holdings have stalled (Figure 3). However, the deeper geo-economic fragmentation spurred by Trump’s aggressive trade policy will entail valuation risks for dollar-holders. In a recent study (Subacchi and Van den Noord 2025) we assess this risk, and the results are briefly discussed in the remainder of this column.

Analytical Framework

We set up a three-country model in which international trade is settled in the currency issued by the ‘monetary hegemon’. The two other countries accumulate foreign exchange reserves by investing in sovereign debt issued by the hegemon, which is considered safe and liquid. One of these countries – the ‘conventional creditor country’ – allows private investors to hold foreign sovereign debt while the other – the ‘emerging creditor’ – prohibits this.

We distinguish between two periods – the ‘short run’ and the ‘longer run’ – with all asset and liability positions unwinding at the end of the second period. Monetary policy does not play an explicit role in determining the overall price level. As a result, movements in the real exchange rates are not broken down into movements in nominal exchange and inflation rates. 1

The real interest rate is the key adjustment variable to establish the optimal mix between home-produced and imported goods in each country over both the short and long term (intertemporal equilibrium), while the real exchange rates adjust to establish the optimal mix of consumption of home-produced and imported goods in each country (intra-temporal equilibrium).

In the ‘conventional creditor’ country, the accumulation of reserve assets by the private sector is a function of the opportunity cost of holding them. This cost is the spread between the risk-adjusted yields on domestic sovereign debt and the reserve asset and the expected exchange rate loss on that asset. The latter is due to the monetary hegemon’s need to run a trade surplus in the longer term to finance the repayment of its foreign-held sovereign debt.

This approach (see also Blanchard et al. 2005) reflects the rising geopolitical tensions coupled with the aggressive trade policy of the Trump administration. It sharply contrasts with the assumption that such debt could build up forever, as embedded in models with an infinite time horizon (e.g. Felbermayr et al. 2023) or in static ones (Cheng and Zhang 2012).

Official investment in the hegemon’s sovereign debt is treated as exogenous in the model. However, official investors face opportunity costs on their holdings as well. While these costs are assumed to have no impact on these investments, it is nonetheless important to compute them to assess the economic soundness of these investments.

Scenario analysis

The model and shocks are calibrated to loosely reflect stylised empirical realities. Starting from symmetric equilibrium (Scenario 0, without cross-border asset holdings), we generate two scenarios. In Scenario 1, the ‘conventional creditor’ and subsequently the ‘emerging creditor’ invest in the monetary hegemon’s debt. Next, the hegemon ‘consumes’ some of the fiscal space thus created by running a larger fiscal deficit. In Scenario 2, we evaluate the impact of geo-economic fragmentation on the opportunity cost of holding reserve assets, and how this cost changes if these holdings are restrained.

According to our simulations of Scenario 1, the demand for reserve assets by the creditor countries leads to an increase in the opportunity cost of holding reserve assets, due to higher real interest rate spreads of the latter against the hegemon and a stronger short-term but weaker long-run outlook for the real exchange rate of the reserve currency. The latter occurs because the hegemon runs a wider trade deficit in the short run and a wider surplus in the longer run to finance its foreign debt repayment.

When the hegemon runs a loose fiscal policy, the favourable yield spreads (for the hegemon) evaporate as the real exchange rate weakens further in the longer run. Since the exchange rate movements outweigh the narrower yield spreads, the opportunity cost of holding reserve assets rises further for foreign investors.

In Scenario 2, we assess the impact of geo-economic fragmentation, which we gauge by increasing the relative utility attached to domestic goods in the intra-temporal utility functions. Next, we assume a cut in the demand for reserve assets, first by the emerging creditor country and subsequently by the conventional creditor country.

Assuming that the demand for reserve assets by the creditor countries remains unchanged, the real exchange rates (and terms of trade) of the monetary hegemon against the other countries must strengthen in the short run to produce the required trade deficit to absorb the demand for its debt. However, they weaken in the long run when this foreign debt is repaid, while investors experience a valuation loss on their holdings. As a result, the opportunity cost of holding reserve assets increases, on balance, for both creditor countries, even though the real yield on the reserve asset increases.

Creditor countries, therefore, reduce their holdings of reserve assets, starting with the emerging creditor country. The real exchange rate of the later now appreciates while the yield on its reserve assets rises. The incentive for further cutbacks weakens as a result.

In a final step, we assume that (public and private) investors in the conventional creditor country follow suit, since the opportunity cost is still considerably higher. The impact of this change on the real yield on the reserve asset and the evolution of the real exchange rate is similar as in the previous step where the emerging creditor cut its holdings of reserve assets. As a result, its opportunity cost recovers somewhat further, and a complete wipe-out becomes even less likely.

Conclusion

We examine whether dollar holders will continue to maintain their positions or reduce their exposure in response to geo-economic fragmentation. We show that the rationale of holding less US sovereign debt is compelling because the opportunity cost of holding it increases. However, cutbacks in the build-up of creditor countries positions of US sovereign debt lowers its opportunity cost. A collapse of the dollar’s dominant position is therefore unlikely, unless countries give precedence to geopolitical brinkmanship over economic rationales.

See original post for references

The Chinese government share (~$750B of total outstanding ~$35T) is about 2%! The chinese private sector debt might bring in another 2%. On the face of it, there doesn’t seem to be much to worry about, just as the Chinese say that losing 3% of GDP worth exports to US will be painful but also overcome.

There must be significant ‘non-linearities’ involved though, intangibles like ‘market confidence’ etc. Why was Yellen taking repeated trips to China to convince them (and failing at it) to up their purchases by $1T — while this would double china’s stake to ~4%, it would hardly be a blip overall.

These is also the story that China prevented the GFC in 2008-10 from blowing up to a depression by buying treasuries. Their aggregate purchase seems to be 500B in a total mkt of about 11T, so about 5% only. Was this more ‘reassurance to confidence fairy’ business?

On the flip, there is no single large buyer to negotiate with now to slow the rise in yield.

If Trump wants to return manufactures to the USA, he would have to dethrone the dollar as reserve currency, at least according to this article. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/americas/2020-07-28/it-time-abandon-dollar-hegemony

Anyone who says the US can get manufacturing back is deluded. Repeat after me: the US is never getting manufacturing back.

See for details: https://x.com/molson_hart/status/1908940952908996984?s=46

We can better manage our inevitable decline if we keep the US a good place to park money and sell securities and maintain our many tourist attractions, from the Grand Canyon to Disneyland to Broadway.

Exactly what Yves is saying, I’m no economist, but most of my family works in small and specialized American manufacturing firms, and even these small firms really struggle to grow simply due to labor supply and other supply chain issues. They’ve ended up spending the last 10 years trying instead to grow their business by reselling European imported products. For reasons I cannot understand, they voted for and supported Trump’s tariffs.

Any gains in business and productivity have been due to automating their manufacturing process. These things are so specialized and nuanced, I fail to see how anyone thinks you can just swap them out.

From this perspective it makes sense that Trump, the reality TV star, is President and he appoints cartoon characters to executive positions. The problem to be resolved is stripping them of actual power, leaving figureheads like the British royal family. Not sure I’m personally a fan of the imagined past Trump et al embody but it doesn’t have to have universal appeal to work as a tourist attraction.

Yes, that is succinct even though the author does give some pointers at the end on what needs to be done in order to bring at least some manufactures back to the USA. There would be a need for a good industrial policy.

To reindustrialize a country, requires a hands-on government directing the initiative.

American elites are not interested in reindustrialization, but in rents.

What is interesting is the minimum 10% fee being charged to any country requesting access to the US consumer goods market!

If there is an intention towards reindustrialization it is the implementation of a war economy in the USA, to be used for collecting rents from foreign countries.

AH

I understand the focus on UST, but the overall net foreign asset (NFA) position of the US versus other developed economies is very negative, and has deteriorated exponentially in the last decade.

You can explore some data here

The US NFA position is -$20T as of 2021. Foreigners love to own foreign assets beyond UST, namely Japan (+$4.7T), China (+$4.2T), Germany, and Saudis. And financiers and banksters love this dynamic as it generates lots of fees and capital gains and asset goosing. Granted we don’t know exactly the make up from this data of the foreign asset holdings, but given the giant negative balance of the US we can make an educated guess.

There seems to be some discussion of this issue (falling treasuries, strength of US$) in the financial press today, the 12th of April. $ now at 1.13 vs Euro, which looks to be a closing low since 2022. It is interesting that Treasuries don’t seem to be moving like an asset considered super safe in difficult times! The implications of this are way above my pay grade but guessing we are looking at significant change?

I think the crux of the matter is in the last sentence – “A collapse of the dollar’s dominant position is therefore unlikely, unless countries give precedence to geopolitical brinkmanship over economic rationales.”

A run on the dollar is uneconomic within the current economic system, but if this turns on geopolitics all bets are off.

The current economic system set up by the US empire, to benefit the US empire. Not only has the empire allocated the most profitable parts (ownership, patents, etc) to the US it also gets one trillion dollars a year (US current account deficit) in goods and services in exchange for IOUs. Countries that tries to climb up the value added ladder without US approval faces the US escalation ladder of opposition support from the US, NGO networks undermining the government, color revolutions, coups, economic blockades, support for armed groups and outright invasions. Taking the IOUs and using them to benefit the leaders and their families and networks is the economic rational thing to do within the system.

No empire lasts forever though, and the US empire is creaking and showing signs of going down. Once it does its IOUs will become worth much less, which in turns makes it economic and rational to buy anything with real value for any dollar assets you have (not only federal debt). If the vassals start thinking that most vassals will start running for the exit, it becomes rational to run. And then we are in geopolitical territory. The empire can’t go after everyone at the same time, if everyone runs the empire goes down, and in the end it is the empire that makes the imperial military possible.

Miran and his ilk clearly either don’t know about or cannot understand Michael Hudson’s “Super Imperialism” which described how the US designed and operates the world’s first deficit empire — and that book is over 50 years old!

The irony is that the US used to understand this — if I recall correctly, the State Department bought many copies of the book and Hudson was brought in to explain his work to many senior US officials, including military personnel.

The deficit IS tribute! The US consumes more than it produces and the currency it issues in return for hard goods (kind of like the old fashioned tribute) gets “recycled” into US treasuries (which “fund” the Pentagon) and Wall Street by the comprador elites in the neocolonial periphery.

Miran and company are either ignorant of this process or they profoundly misunderstand it. The issue they ought to be concerned about is how badly the US (mis)leadership class has mishandled the distribution of the benefits of the system — THAT is what has led to the deindustrialization and immiseration of the nation!

But of course they are utterly blinded by neoliberalism, and the wages of neoliberalism are death. So, having sown the wind, they now reap the whirlwind …

The UK’s contributions to UK+EU holdings of Treasuries is remarkable from Figure 2, especually in its growth in the past decade.

So remarkable, it has jogged my memory that I think, according to Brad Setser, a lot of Chinese purchases are through Cayman asset managers. My guess is that the ramp in UK holdings is actually Cayman asset management affiliates of UK bank holding companies.

This doesn’t change the economic analysis of the piece but it does change the weight of China in the current holdings and thus how far disinvestment / opportunity cost management / geopolitical brinksmanship may have to go.

For what it’s worth, a recent article on US debt in the form of US treasuries with some useful breakdowns. I knew that money put into Social Security gets turned into US treasuries but was surprised to see that it is only 7% of the total-

https://www.reuters.com/markets/us/who-owns-us-debt-2025-02-10/

Yanis thinks trump might win, and some industry will come back.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ax7TtJrEcKQ

Yanis Varoufakis Explains Trump’s Tariffs

167,372 views Apr 10, 2025

🇺🇸❤️PLEASE SHARE IF YOU LOVE AMERICA❤️🇺🇸

This week Nexus talks to Yanis Varoufakis. He was Greece’s motorbike riding finance minister during the Greek debt crisis in 2015. Some called him the rock star finance minister for resisting the faceless bureaucrats from the European Union, the IMF – and the rapacious bankers. We get his views on Trump’s Tariffs, Free Speech in the West, and Transhumanism where he warns we’re all at risk from the techno-feudal lords who are taking over the world.

00:00 – INTRO

00:22 – WHO IS YANIS VAROUFAKIS

00:42 – COMING UP

01:10 – TRUMP ANNOUNCING RECIPROCAL TARIFFS

01:59 – WHAT ARE TARIFFS?

02:58 – ARE TRUMP’S TARIFF’S RECIPROCAL?

06:20 – TRUMP’S FORMULA

08:47 – IS TRUMP DOING THE RIGHT THING FOR AMERICA?

09:24 – NIXON SHOCK

15:10 – 50 COUNTRIES NEGOTIATING?

16:09 – AGREEMENTS?

17:19 – US AND CHINA TARIFFS

18:55 – STOCK MARKET PERFORMANCE

20:42 – US NATIONAL DEBT

23:00 – FREE SPEECH

25:05 – TRANSHUMANISM

30:18 – WHY YANIS RESIGNED

32:43 – GREECE ECONOMY

Yanis also thought Greece could prevail against the Troika. And he had much better access to information then. His track record is poor.

I find him useful analytically, but as you point out, predictions are entirely another matter.