Yves here. European NATO members, with few exceptions, have worked themselves into a frenzy over the belated recognition that Russia is winning the Ukraine war and the US is about to leave them to their own devices, defense-wise. That of course means the evil Putin will soon be in Paris! Hence militarism is now in vogue, even though, with UK and European economies already in a sorry state due to sanctions-induced energy cost increase, they are under budget stress. Big arms programs will only make that worse.

So “military Keynesianism” is the way to square that circle, at least in theory . But how well will that work in practice?

By George Georgiou, an economist who for many years worked at the Central Bank of Cyprus in various senior roles, including Head of Governor’s Office during the financial crisis

By spending more on defence, we will deliver the stability that underpins economic growth, and will unlock prosperity through new jobs, skills and opportunity across the country

– Keir Starmer, press release, 25 February 2025

Introduction

Europe’s commitment to rearm as a response to the perceived threat from Russia, has been partly justified on the grounds that an increase in military spending will stimulate economic growth. In other words, military expenditure is seen by policymakers as a form of Keynesian pump priming. This is a neat argument used by European policymakers desperate to persuade their electorates to accept large increases in defence spending at the expense of the welfare state. However, there is very little evidence that Keynesian militarism will actually provide the intended result. Indeed, the economic reality of military production and procurement undermines the implicit assumption that the defence spending multiplier is sufficiently large to generate a Keynesian type stimulus.

Military Production and Procurement

A significant proportion of military equipment in some European countries is sourced from overseas rather than domestically produced. Weapons systems are imported from America, Israel, South Korea, and elsewhere. Table 1 below has been adapted from a table in the 2024 edition of Trends in International Arms Transfers published by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute in March 2025. The most striking observation is the dominance of arms supplies from America. The share of imports from America varies from 45% (Poland) to 97% (Netherlands). As SIPRI states:

“Arms imports by the European NATO members more than doubled between 2015–19 and 2020–24 (+105 per cent). The USA supplied 64 per cent of these arms, a substantially larger share than in 2015–19 (52 per cent)”.

Table 1- Selected European NATO importers of major arms and their main suppliers, 2020-24

Source: Table has been adapted from Table 2 in SIPRI’s Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2024

Due to capacity constraints in the European arms industry and the dominance of American technical know-how, it is unlikely in the short to medium term that Europe will be able to replace American weaponry with domestically produced armaments. Hence, an increase in European military outlays will benefit the US economy significantly more than Europe.

Even in those countries, like France for example, where weapons systems are sourced primarily from domestic producers, many of the components are often imported. Thus, the impact of military spending on the domestic economy is limited.

Another factor that needs to be considered is the production process. The increasing sophistication of weapons systems involves capital intensive production methods rather than the labour-intensive methods that were common prior to the 1980s. The ever-increasing sophistication of fighter jets, tanks and war ships often results in long lead times and cost overruns. The post-WWII history of weapons systems is also replete with examples of armaments that are unreliable or unsuitable. This is particularly the case with tanks, fighter jets and ships, but similar problems have occurred with relatively simple products. For example, the UK government is currently having to replace 120.000 body armour plates due to cracks.

Technological Spin-Off

Advocates of Keynesian militarism argue that one of the ways in which military expenditure stimulates economic growth, is through technical innovation in the military sector which eventually spins-off into the civilian sector. The empirical evidence for technological spin-off is inconclusive. Some academic studies have found that during the cold war, when there was an arms race and military outlays were higher than the post-cold war period, there was some evidence of a technological spin-off. Other studies have found little or no evidence of spin-off. Indeed, the spin-off tends to be in the opposite direction, from the civilian to the military sector, sometimes referred to as ‘spin-in’. A 2005 research paper by Paul Dunne and Duncan Watson using panel data, concludes as follows:

One of the problems of measuring the impact of spin-off is the long-time lag between the onset of military R&D and actual applications in the civilian sector. These time lags can stretch over several years thus overlapping both the economic dynamics of the civilian economy and the interplay between spin-off and spin-in. It thus becomes difficult to disentangle cause and effect.

The Real Beneficiaries of Rearmament

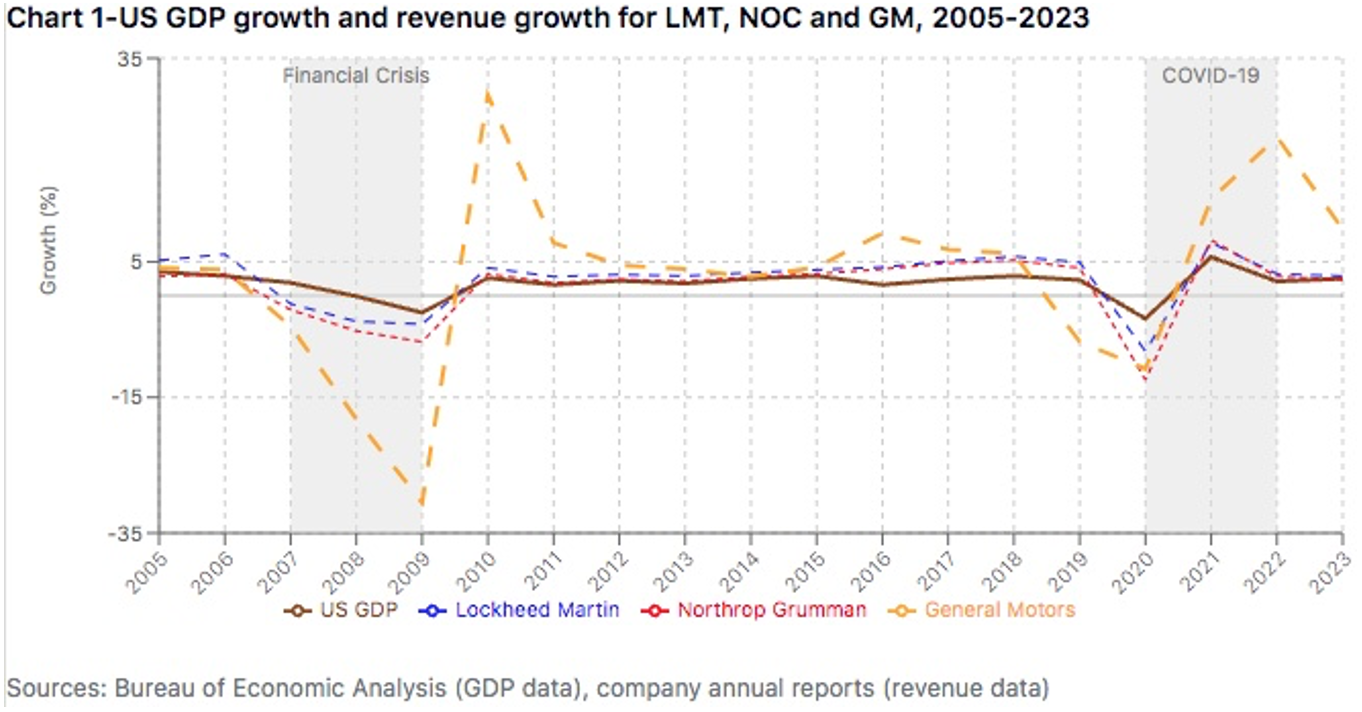

While politicians across Europe try to fool themselves and their electorates that increased military spending is a form of Keynesian stimulus, the real stimulus will be in the profits and stock price of the large arms manufacturers as well as the bank accounts of corrupt state officials. In an article published in Naked Capitalism on 31 January of this year, I argued that arms producers are the main beneficiaries of conflict. Although there is nothing new in this argument, it was useful to provide some numbers. Chart 1 below is taken from the January article and illustrates the stable performance of two large American arms manufacturers in relation to the instability of a non-arms manufacturer.

As regards corrupt state officials, the history of arms contracts embroiled in corruption is long. The interested reader can find them on the Internet. For the purposes of our discussion, a pertinent example is the case of Ursula von der Leyen’s handling of military related contracts when she was Germany’s minister of defence between 2013 and 2019. Allegations of impropriety and implicit corruption surrounding these contracts, still linger. This is the same von der Leyen who in March of this year proposed setting up a European Sales Mechanism that would allow the pooling of military procurement using an EU defence funds. Von der Leyen’s murky past as German defence minister, together with her controversial handling of the Covid vaccine contracts, should serve as a warning.

Conclusion

The economic narrative used by politicians in European NATO countries to justify increases in military spending, needs to be viewed with a dose of skepticism. Ultimately, any decision to increase military expenditure needs to be based on military and strategic considerations rather than perceived economic benefits which may or, more likely, may not materialise. Nor should the supposed economic benefits be used to deflect from the discredited austerity agenda that seems to be now firmly back on the table. Keynesian militarism is a poor substitute for Keynesianism.

A counterpoint to this article is the argument (not that I agree with it, but it bears mentioning in this context) that Russia’s economy is chugging along nicely due to Keynesian pump-priming in the form of sharply boosted defense spending (i.e., “Putin’s war economy”). Getting my retaliation in first, so to speak, let’s take a look at this counter-argument.

Firstly, there are several differences between the situations in Europe and Russia, which make it less likely that this sort of military spending will re-vitalize Europe’s moribund economies.

1. RU imports little weaponry, aside from (mostly Chinese) electronic components and (very recently) some Iranian drones and missiles and North Korean ammo; pretty much everything it uses in battle is home-grown

2. RU has a lot of under-utilized industrial capacity left over from the USSR; and in contrast to Europe, RU never allowed its defense-related heavy industries to go completely to pot, even during the 1990s

3. Much of RU’s defense manufacturing is still relatively labor-intensive, hence much of the higher spending ends up in the pockets of workers in provincial industrial cities, which ends up benefiting the local economies. Plus a lot of the defense budget increase is going towards salaries for professional contract soldiers (as opposed to conscripts), which again boosts local economies (as relatively few of these well-paid troops come from Moscow or St Pete).

4. RU’s defense sector is overwhelmingly state-owned, therefore higher spending doesn’t simply end up lining the pockets of private shareholders and company execs with stock options (although corruption is a problem).

Secondly, I question the basic idea that Russia’s overall economy is even benefiting from boosted defense spending. Russia’s recent economic performance probably has more to do with Western sanctions which are (counter-intuitively) benefiting Russia by:

a. Encouraging local production via import substitution

b. Allowing lower-cost-but-decent-quality Chinese products to substitute for more expensive Western equivalents, leading to increased efficiency via lower costs

c. Forcing Russian money that (pre-sanctions) used to flee offshore to remain at home instead, thereby percolating through the domestic Russian economy in a positive multiplier effect

I don’t think military pump-priming is a good idea in peacetime, neither in Russia nor in Europe, and the Europeans will simply be digging themselves into an ever-deeper economic hole if they follow this path.

During the cold war a Soviet general observed that US weapons are always “cutting edge” (unfortunatly the cycles extend so that the old wunderwaffen are shoddy before replaced) which is the enemy of good enough. US industry made assured margins on designing the wunderwaffen which were often not good as advertised.

In some cases the US’ wunderwaffen are old before they are fully (?) tested. See F-35.

Soviet and now Russian designs in many areas of weapons are evolving designs…. Technology phases on going.

Also Russia has a much lower need to import basic materials and energy!

>”Also Russia has a much lower need to import basic materials and energy!”

It would be interesting to have a chart that compares what percentage the Russians of that need to import v. the Europeans.

How high is the level of Russian autarchy – 70%, 80%? – in energy and rare earths et al. necessary for their “MIC”. In contrast to Europa. Since these are the things Europeans cannot change even in decades.

Maxwell Johnston: I don’t know much about the Russian defense industry, so I appreciate your four numbered points about the quality and quantity within that sector. Here in Italy, as you know, the names of Leonardo, and now Iveco, keep coming up as the sources of the new bonanza and the beneficiaries of “Readiness.” (I always associated Iveco with buses and trucks, but evidently, Iveco also makes military vehicles.)

I have a feeling that you can assess better than I how much / if Leonardo and Iveco are going to be showered with funds in this new Land of Defense Cuccagna.

I have read articles about your second part, the many unintended benefits to the Russian economy of sanctions. It appears that pre-/post-sanctions, the Russian agricultural sector was on the upswing.

Because of sanctions, Russian agriculture has diversified and engaged in import substitution. This includes the many anecdotes about Russians creating substitutes for formerly imported Italian parmigiana, romano, and mozzarella.

Further, the sanctions meant that many Western chains pulled out, which meant “Russifying” the infrastructure of former McDo’s and such. This has led to benefits for the Russian economy.

Russians’ travel options outside the country are now limited — which affects the flow of money outward.

So, the “war economy” may not be all about defense spending, and rather about great growth horizontally (as it were), across the whole economy.

Others may have more detailed assessments than I do.

>”So, the “war economy” may not be all about defense spending, and rather about great growth horizontally”

Could one go as far as suggesting even a redistribution of wealth within the country making the riches more equally distributed?

“Cuccagna” — I had to look that one up. Good one.

Italy, amazingly enough, is one of the world’s top arms exporters (number 6 on this list, admittedly far behind number 1…..), so I’m sure its contractors will figure out how to catch any free money falling from the cloudy European sky:

https://www.statista.com/statistics/267131/market-share-of-the-leadings-exporters-of-conventional-weapons/

As for cheese (a far more important subject than all this talk about ‘defense’ budgets): the Russians have seriously upped their game since 2014. Back in the good old days of cheap direct airplane flights between Tuscany and Moscow, I would carry several cheeses in my Russia-bound suitcase (along with wine, panettone, panforte, olive oil, cantuccini, etc). No need to anymore, as the Russian cheeses are perfectly OK (and cheap), although they still haven’t figured out how to make parmigiano.

The question is why military Keynesianism even works? You are just killing/maiming people and destroying stuff. Even if it doesn’t end in war, you are still making stuff that can’t be used for anything useful, yet people and the economy end up being in better shape.

IMO the real reason is it’s the only time capitalists actually need common folk, not only as cannon fodder on the front, but also to make all the things needed by the cannon fodder. And with gun to their heads, so to speak, the ruling class is willing to cede some of their power/money to the people.

But despite all the screeching in media, I don’t think EU elites truly believe there is going to be war with Russia and they will need people to defend them in their castles. And so they will just steal the money, all of the 800 billion or whatever, and nothing will trickle down to prop up the economy. Meanwhile, Putin keeps upping the signing bonuses, the bonuses for killed family members, for factory pay for people who mass manufacture weapons, etc., while the oligarchs have their wings clipped a bit.

In Europe the story is explicitly that the social system needs to be dismantled and overall, people will be poorer. Which obviously means there will be no economy growth.

If we take it as natural or acceptable that our economy, what we do all day, requires a surplus population, and surplus production, then military Keynesianism makes a lot of sense, as does imperialism, an effective synonym. Hanah Arendt wrote about it (the latter term) as surplus populations chasing surplus commodities, guided, of course, by the (mainly financial) ambitions of their rulers. I appreciate your re-direction on this, NN Cassandra; it can be easy to get bogged down in the intricacies of the market impacts of these things, especially on a forum like this, where the expertise of many is in that area, but if there’s a signal that needs boosting on this front it’s yours and those like it.

I may have written about it here before, but G.B. Shaw’s Major Barbara has, I think, the last word on the arms industry (‘defense spending’) and the misanthropic ways it twists our thinking; we have to discount most of what makes life worth living, but if we do, then it makes sense to make money by killing and driving others to do so. In my edition, Shaw writes a long introduction, which I heartily recommend, aligning himself with Nietzche regarding Christianity and advocating for socialism. Hoping this finds you all well.

Looking at actions and not words – cutting healthcare and spending more on weapons – explains it all.

I think Russia’s “military keynesianism” is very different from what the Europeans are proposing. Firstly, the massive sanctions of Russian industry allowed the state to take control of many sectors beyond simply investing in defense spending. All of those food products, electronics brands, etc., that were formerly Western brands are now Russian. Maybe I’m wrong, but I’d suspect that encourages significant re-investment in Russian companies and brands.

Furthermore, I believe the Russian state has far more centralized control of production and major industries. I can’t imagine the British state doing much more than providing expensive contracts to arms manufacturers that are bound to go beyond schedule and over budget. I get Russia isn’t the Soviet Union anymore but it also isn’t the hollowed out husk that is the British economy either.

I agree with George Georgiou’s summary of the economic problem and of the problem of the quality of European leadership. Two quotes from above that I would like to highlight here:

1. “While politicians across Europe try to fool themselves and their electorates that increased military spending is a form of Keynesian stimulus, the real stimulus will be in the profits and stock price of the large arms manufacturers as well as the bank accounts of corrupt state officials. In an article published in Naked Capitalism on 31 January of this year, I argued that arms producers are the main beneficiaries of conflict.”

Smedley Butler: War is a racket. Randolph Bourne: War is the health of the state.

2. ” Von der Leyen’s murky past as German defence minister, together with her controversial handling of the Covid vaccine contracts, should serve as a warning.”

Yes, von der Leyen is no Altiero Spinelli, nay, not even a Charles de Gaulle.

Also, Dwight Eisenhower, who knew a great deal about war, unlike the current crop of cowards and keyboard warriors (à la Hillary Clinton, Kaja Kallas, and Keir himself) had this to say about allocations for war matériel:

I don’t think the author really understands what military Keynesiansm is, (and note that the phrase “Keynesian militarism” is meaningless: I have never heard it used by economists.) The author seems to think it’s all about equipment, and R and D spinoff, which is not true. But then the Cyprus National Guard is just 12,000 strong…

The idea behind MK is simple, and is just a reflection of the fact that government spending creates demand in the economy, and defence is a type of government spending. Some types of government spending (in education for example) have a low import content, some (like IT products and hydrocarbons) have a high import content, but even IT products, for example, create jobs in shops, distribution, repair, maintenance, operations and so on. Defence spending has a higher import content than many other kinds of government spending, and because it is quite capital intensive, it creates on average fewer jobs than, say, investment in construction projects. However, and in spite of what the author seems to believe, spending on direct equipment purchases is only a small part of defence spending – typically 25-30%, of which a large part is either of civilian equipment (cars, trucks, electronics etc. etc.) or militarised civilian equipment.

Overall, Europe does not import much defence equipment. The figures in the table show that the whole of Europe only accounts for about 10% of the world import market, and quite a large proportion is European countries exporting to each other. What we’re seeing here is essentially the F35 programme, which temporarily (as in once in a generation) boosts the import content. The last time this happened was with the F16 in the 1980s. The vast majority of tanks, helicopters, ships etc. are European, bearing in mind that even in the US the import content of most equipment is above 50%.

In any case, the main benefits of defence spending are not from equipment. Assume (as economists say) that your armed forces are 100,000 strong and you decide to double them in size over ten years. Obviously, this means that 100,000 more people are employed than would otherwise be the case. But in reality, you’d probably need to employ at least half that number of non-military as well, for everything from administration to cleaning barracks to cooking food. You will then buy hundreds of thousands of extra uniforms, boots etc each year, as well as a lot more telecommunications equipment, computers radios etc. You’ll have to buy huge numbers of civilian vehicles and employ people to service them, as well as buying much more food, fuel, utility services, and everything required to support service personnel and their families, including schools, sports centres and so on. You will probably need to construct new barracks, new training grounds, airfields, equipment stores and everything else. With the multiplier effect, this would probably create at least 250,000 jobs in total. This is what happened at the start of WW2, when unemployment basically disappeared.

Defence is not the most efficient way to for governments to stimulate the economy, but it provides a stimulus nonetheless, something which they author seems to have difficulty with.

IIRC, there are legal constraints on the annual and cumulative net injections of State Money into EU economies. If the increase in defense spending is offset with reductions in social welfare spending, it’s conceivable to me that the reorientation of budget priorities might actually be contractionary, if the multiplier effect for spending directed at the lower reaches of the income distribution is higher than for the middle of the distribution that would benefit from increased defense spending.

Are they going to relax the constraints of the Growth and Stability Pact?

That would clarifying in terms of what EU rulers really value.

Yes, the Maastricht Treaty is expressly anti Keynesian.

Only “the market” can determine credit allocation beyond, IIRC 3% of GDP.

Foreseeable problems foreseen.

Frederic Bastiat and notably President Eisenhower pointed out the lack of worth from war spending against almost any other use of the resources.

A weapon system has value when it defeats an enemy all other worth is speculative.

A soldier’s pay creates demand but the soldier makes nothing to resource his buying.

Imagine what U.S. federal debt would be if $40 trillion had been spent in half for things other than war material l

Eisenhower was not an economist, and simply pronounced what his speechwriter (who as I recall was no economist either) put in front of him. The speech was given at a time of strong anti-militarism in the US (“Seven Days in May,” “Dr Strangelove”.) The “crowding-out” hypothesis isn’t true anyway, unless an economy is already overheating from excess demand.

I don’t know why it’s so hard for people to understand that most defence spending doesn’t go on “war” at all, but on military and civilian salaries, infrastructure, logistics, consumables, civilian standard equipment and so forth. Any White Paper from a major nation will give you a breakdown. And as for economic effect, I can’t see why a sum of money spent by a soldier (or a cleaner in the barracks, or a teacher of service children) is of less worth than a sum of money spent by a commodities trader, a YouTube influencer or a private health accountant. As Keynes himself said, you would theoretically get some effect, during times of unemployment, from hiring one group of men to dig holes, and another group to fill them in again.

But that’s not really the point. Defence spending is a (relatively) poor way of providing an economic stimulus, but I don’t think anybody really believes that an economic stimulus would be the point of rearmament. In reality, the problem European forces have is not with equipment but with personnel: they can’t man the equipment they do have, let alone any extra they might buy. And the (sizeable) European armaments industry is working considerably below capacity. If you could start remilitarising Europe, the main initial effect would be on employment levels.

Oh, and I almost forgot: Collaborative projects in Europe go back to the 1970s, and there has been a European Defence Agency for the last twenty years. It’s amazing what you can get away with not knowing and understanding when you’re an economist.

“It’s amazing what you can get away with not knowing and understanding when you’re an economist.”

This is simultaneously golden and evergreen …

Contrary to what you state, the term MK has been used by other economists. For example, Varoufakis used it as recently as March of this year. Another example is Mark Harrison, who used it as part of a lecture at Warwick University in 2018/19. And so on…

I don’t understand what relevance the size of the Cyprus National Guard has to my arguments, unless you think that I based my analysis on the military sector of a small island in the Eastern Mediterranean. If you want to quote numbers, how about the 74.000(approx) full-time personnel that makes up the British Army, which would not even fill up Wembley Stadium. By how much would Starmer have to increase the British Army before a significant multiplier effect made the kind of impact on the UK economy that he and his ministers have been telling the media?

I don’t know if that’s quite the logic the euroserfs are employing to get from here to there…

Supposition 1 – European states, to a greater or lesser extent, have become US vassals. We can argue over when this happened to whom (I’d argue Britain got there in 1956, but whatever), and to what extent. But essentially, when Washington, and not just the White House, says “jump”, the EU and Britain say “sir, how high, sir”. And remember, this includes not only the political layer, but the other key stakeholders (e.g. the local billionaires) as well.

Supposition 2 – America’s goals in Europe, both viz. the Europeans (euroserfs!) and the Russians, have not substantively changed. Evolved, yes, especially in light of the accelerating Ukraine fiasco, and the…peculiar notions of some of the people presently in the White House (not just Trump). But notice, at no point is anyone discussing (in public) withdrawing from or disarming Ukraine – just a freeze. No-one is talking about pulling NATO back from Russian borders, only not deploying medium range missiles on top of what’s already there. And most of Washington still thinks that, ultimately, Russia needs to be destroyed and the carcass looted; it’s just that the people in the White House “today” want a more aggressive China pivot than before (seemingly forgetting that “confronting” China without dealing with their Russian allies is strategic lunacy).

Supposition 3 – irrespective of (1) and (2), European economies since the end of the Cold War were partially built on the Russia-China trade. We’ll buy cheap raw materials, not just gas, from Russia, create processed goods, sell these to China (and a little to Russia), capture the spread. I would argue this was going to end regardless, especially with China scaling up high-end manufacturing and exports, but that was the trade for three decades or so. Now, they’ve cut themselves off from the Russians – at the behest of the Americans – and will likely be forced to cut themselves off from the Chinese, both in the name of Trump’s “pivot”, and simply to protect themselves from being flooded with the same stuff the Europeans used to make, but cheaper.

So if you’re a euroserf, how do you read this, and what do you do?

You want to please your American masters, keep the pressure up on the Russians, and somehow do SOMETHING to not completely die economically. Rearmament, at least back to the Cold War levels, is an easy answer that – in theory, much less so in practice – ticks all three boxes. The Poles, of all people, were way ahead of the curve here when they started to build their thousand-tank army, half American, half South Korean, even before the SMO kicked off in 2022. [And I remember at the time Belarus was incredibly worried about this, since the Russians hadn’t yet taken it under their wing, and since, logically, that’s the only place that thousand Polish tanks could go.]

To JUSTIFY this, you need to drum up the Evil Russians Are Coming hysteria. And, hey, I fully expect both Ana and Lena to actually believe this while doing their 360-degree turns. But again, I don’t think the logic here has much to do with any “actual” Russian danger, or with how things are going in Ukraine. The Big White Master wants us to rearm, AND rearmament will save us from the economy going ker-plunk and our being swept out of power. So there you go. Maybe I am being a bit too cynical about this, but that’s the decision flow that I am envisioning here.

Sorry, your suppositions are no longer true. The EU is sabotaging the US by refusing to allow the Russian agricultural bank to reconnect to SWIFT, which is one of the two components of the Black Sea grain deal that Trump wanted to revive. The UK and France and others running around trying to get some kind of peacekeeping force and the various EU leaders meeting with Zelensky has shored up his appearance of legitimacy at home, another spanner in the US efforts to get a peace settlement.

And since you missed it, military Keynesianism is building your OWN arms, which is what the EU wants to do despite their lack of present capability. Admittedly, they don’t appear very skilled as to how to get there.

There is a minor discussion on this in Germany (instead of a huge uprising and resistance)

JUNGE WELT sums it up in this text. Again I post the entire piece.

IMI (Information Center on Militarization ) is an old German NGO located in Tübingen against militarism and an excellent source on everything related to NATO and the arms industry:

https://www.imi-online.de/

Ifo is the neoliberal German economics institute in Munich:

https://www.ifo.de/en

German version:

https://archive.is/URt0j

“(…)

Defense has no effect

Military debt is reflected in gross domestic product, but has no positive effect on economic performance. IMI vs. Ifo

by Susanne Knütter

This lie, too, is part of the “turning point”: armaments are good for the economy, good for the economy, and that, as we know, is good for the country. Economic institutes close to capital provide the relevant studies. For example, the Munich-based Ifo Institute reported on Tuesday: “Due to the booming arms industry, the northern federal states are decoupling from the economic downturn in Germany.” According to the report, gross domestic product grew in only five of the 16 federal states in the last quarter of 2024 compared to the previous quarter.

The three large northern federal states in particular are performing better than the rest of the country: Lower Saxony’s economic output grew the most at 1.4 percent, followed by Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (plus 1.1 percent) and Schleswig-Holstein (plus 1.0 percent). Hesse and Hamburg also reported slight increases. The “upturn in the defense industry” is key, said Ifo economic expert Robert Lehmann. In Hesse, financial and corporate service providers are doing particularly well.

In reality, the calculations yield a different result. ” If huge amounts of money are poured into any sector of the economy through debt in the short term, this naturally has an impact on GDP,” states a study published on April 8 by the Information Center on Militarization (IMI). In the long term, however, military spending has by no means a positive effect. On the contrary, non-military public spending has a more positive effect on the economy and employment than spending on arms purchases. The IMI points to cross-country comparison studies according to which a one percent increase in military spending over 20 years would lead to a nine percent decline in economic growth.

And arms hardliners among think tanks aren’t hiding this reality either. The IMI points to the Bertelsmann Foundation and the German Council on Foreign Relations. Their representatives, Christian Mölling and Torben Schütz, wrote candidly on capital.de in September : “Armament is expensive and unpopular – which is why some politicians are coming up with a new idea: The billions spent on arms could be an economic stimulus.” But the bottom line is, “the idea of arms Keynesianism is a well-intentioned attempt to mediate investments necessary for security policy through prosperity effects.” It is well known that armaments are a “relatively poor investment when it comes to promoting the national economy.” Nevertheless, it is not a plea against rearmament. Mölling and Schütz conclude: “Even if not a cent of the billions were to remain in German industry, we should not stop investing.”

And because a particularly large amount of money has been released for the military, and a significant portion of the special infrastructure fund will also be used for purely military purposes, interest in the defense industry is high. For example, last week the Saarland state parliament debated motions from the SPD and CDU to attract additional defense companies and projects. According to a report by Saarländischer Rundfunk (SR) on April 10, the defense industry represents a huge opportunity. Saarland could use it to improve security in Europe and simultaneously improve its own economic situation.

Saarland’s Economics Minister Jürgen Barke of the SPD stated in the SR report that he had sent invitations to leading arms companies early on. Minister-President Anke Rehlinger intends to hold an arms summit soon. According to SR, the AfD parliamentary group called for “door-to-door canvassing” of arms companies. The ruling SPD’s motion, entitled “Civil and Military Turning Point: Opportunity for Economic Diversification and Protection for Europe,” was passed with its own votes.

(…)”