“Back to Normal”… Erm, Not Quite.

Once again, a major UK retailer has provided a perfect demonstration of what can happen when the tightly coupled digital payment systems that underpin our seamless consumption lifestyle suddenly buckle. Millions of customers of Marks and Spencer, one of the country’s largest and oldest high street retailers, have had to endure a week of operational mayhem after the retailer suffered what it calls a “cyber incident.”

The problems began during the Easter weekend when M&S customers started reporting issues with contactless payments and online order delays. On Tuesday, the company confirmed that it was dealing with a “cyber incident.” Then, on Wednesday, it told the media that its customer-facing operations were back to normal. But that didn’t last long. A day later, it had little choice but to take some operations offline as part of its “proactive management of the incident.”

M&S has also paused click and collect orders and stopped contactless payments being made. It has also stopped taking orders at some of its international websites. Staff at the company’s London HQ were told to stop using the building’s wifi. Its shares are currently down over 6% today (25/4).

While M&S has notified data protection supervisory authorities and the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC), it has not disclosed any concrete details about the nature of the cyber incident or whether customer data has been compromised. Meanwhile, no ransomware gangs or other threat actors have claimed responsibility for the attack, possibly because “the attackers are attempting to pressure M&S into paying an extortion demand,” said cybersecurity firm Cytex.

If ransomware is indeed behind the attack, that data will probably have been stolen and is being used as additional leverage to compel payment. And when it comes to customer data, M&S has vast deposits of the stuff. The company has over 5 million store card holders while its Sparks loyalty scheme has over 16 million members globally, including millions of customers in India where it has roughly 100 stores.

The company’s stores have remained open throughout the week. However, it has stopped taking orders through its website and app. As the BBC reported on Thursday, the chaos and uncertainty show no sign of letting up as the fallout from the “cyber incident” continues to hamper operations:

Contactless payments have since been restored, the BBC has been told, however this has been questioned by some customers.

BBC staff have described witnessing the impact of the suspension of contactless payments.

At Euston station, in London, shop staff were seen shouting that it was cash only as the payments system was down. Disruption was also seen in Glasgow, and a store at Edinburgh Haymarket seemingly closed early.

M&S says it had made the “decision to move some of our processes offline to protect our colleagues, partners, suppliers and our business”.

But stores remain open and customers could “continue to shop on our website and our app”, the statement added.

But confusion has reigned on social media amongst M&S customers.

The firm has responded to some posts on X (formerly Twitter) in the past few hours advising customers contactless payments can be taken in stores

However, this has been contradicted by some individuals, with one saying: “That is wrong – only chip and pin or cash is working”.

In other words, the legions of shoppers who exclusively use mobile payment apps for their purchases will have walked away empty-handed. According to UK Finance, a British trade association for the UK banking and financial services sector, as many as one-third of UK adults now use mobile contactless payments.

When it comes to embracing contactless payments in general, the UK is ahead of most of its peers, including the US, which explains why payment outages in the UK cause so much chaos. Whereas contactless payments are becoming increasingly common in the US, they are more or less ubiquitous in the UK. Many of my friends from the UK boast about not having used cash since the pandemic. Judging by this Reddit thread, it’s a generalised trend.

Contactless transactions in the UK surged from 6.6 billion in 2018 to 18.3 billion in 2023, according to a study by the credit card processor Clearly Payments. To put that in perspective, the US, a country with a population five times larger than the UK’s, registered a slightly lower volume of contactless transactions. The UK’s adoption rate for contactless payments, at 93.4%, is only bettered by Singapore (97%) and Australia (95%), according to Forbes.

Scrapping the Cap

In 2024, a record 94.6% of card transactions of all eligible in-store transactions were contactless, according to Barclays Bank. The UK’s main financial regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, is even considering scrapping the cap on contactless card payments, which limits the amount shoppers can spend on one purchase to £100.

The limit is currently in place to reduce the risk of fraud and ensure consumers can make secure payments. Removing it would bring the UK in line with the US, where there is no fixed limit.

It would also make it even easier for British consumers to splash their money, which would be great news for retailers. The frictionless experience of just tapping and going not only reduces checkout times but also makes it easier for people to spend their money, or bank credit, without thinking about it.

That is also good news for banks. The amount of credit card debt in the UK — and household debt in general — has ballooned so much in recent years that it is cutting into people’s ability to get a mortgage, reports the FT. Outstanding balances on credit cards grew at an annual rate of 5.9% in the 12 months to January 2025, according to data from UK Finance. About half of these incurred interest.

Most of the articles on the issue in the legacy media pin the blame on the cost of living crisis and recent rises in interest and mortgage rates, while the fact that spending money is quicker, easier and more “painless” than ever — and is about to get even easier — is routinely ignored.

The UK’s love affair with contactless payments comes with another hefty price tag: increased fragility.

This is not the first time that problems with digital payment systems have caused mayhem on the British high street and retail parks. When Visa’s payment system for Western Europe suffered a 12-hour outage in 2018, the chaos it caused in the UK was particularly acute due to the fact that a staggering £1 in every £3 of all retail spending passed through Visa’s systems accounts — and that was seven years ago!

In May 2024, the supermarket giant Sainsbury’s suffered a massive outage that disabled contactless and mobile payments across all of its stores for an entire Saturday. Sainsbury’s blamed the outage on a software glitch that impacted its online ordering system and contactless in-store payments.

To compound matters, hours after Sainsbury’s system went down, Tesco, the UK’s largest supermarket chain, with some 4,000 stores, announced that it, too, was having to cancel online orders due to a “technical issue.” As we reported at the time, “in a country where the overwhelming majority of people have abandoned cash in favour of the speed and convenience of contactless payments and where banks have been closing branches and ATMs at breakneck speed, making it harder for their customers to access cash, the result was chaos.”

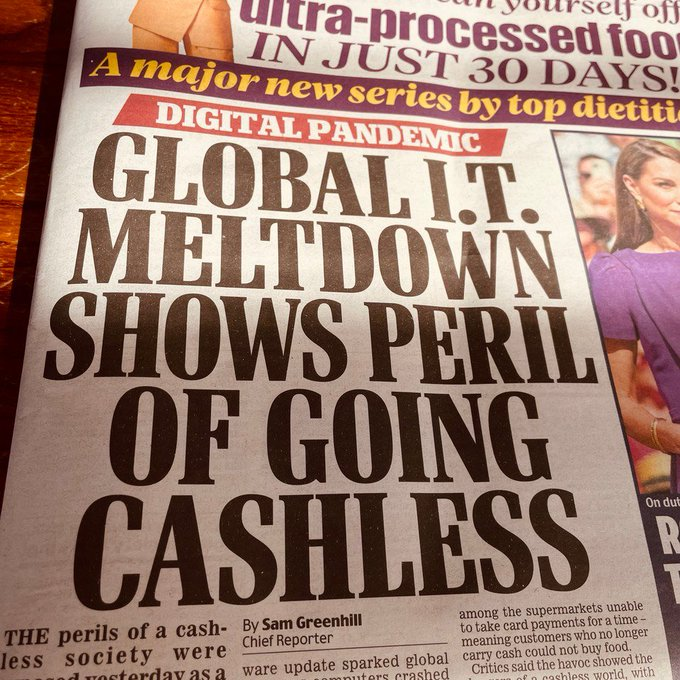

A couple of months later, when the Crowdstrike IT software glitch brought down global IT networks, the UK was once again disproportionately impacted. Four of the country’s largest newspapers — The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph, The Times and The Daily Mail — even ran articles on how the global IT outage had underscored the fragility of a cashless society. The Daily Mail plastered the message across its front page:

Cash Does Not Crash

This is one of the most important arguments in favour of cash, and one that we keep banging on about: the resilience it provides to a country’s overarching payments system. Put another way, cash does not crash. It does not fail in a power cut or seize up during a cyber attack or software outage (though, of course, ATMs might). By contrast, digital payment systems generally need a stable and continuous internet connection and power supply to process transactions. They are also vulnerable to cyber attacks.

This is a lesson central bankers in Sweden, one of the world’s most cashless economies, are frantically relearning. From our post, “The World’s Oldest Central Bank Keeps Sounding Alarm on Fragility of Cashless Economies. Are Other Central Banks Listening?”

After playing a part in the wholesale removal of cash from Sweden’s economy, the Riksbank is now trying to reverse some of the damage it has caused. It is not the only Scandinavian central bank to have flagged up the fragility risks of exclusively digital payment systems. In 2022, the Bank of Finland recommended that the use of cash payments be guaranteed by law. Like all Nordic countries, Finland is a largely cash-free economy. But like Sweden, it has begun to see the risks of going too far, too soon.

Since then, Norway has also brought in legislation that means retailers can be fined or sanctioned if they refuse to accept cash. The government has also urged citizens to “keep some cash on hand due to the vulnerabilities of digital payment solutions to cyber-attacks”. As The Guardian put it, “Nordic countries were early adopters of digital payments. Now, electronic banking is seen as a potential threat to national security.”

The same, unfortunately, cannot be said of the UK, where successive government, as always in the pay and service of the big banks, refuse to taking any action to protect the use of cash in retail settings. An early day motion tabled in parliament in February called for the government to implement legislation to require all businesses in the UK to accept cash, but ministers have steadfastly refused.

This makes it even more impressive that cash use has rebounded for the past two years despite the concerted efforts by the government, banks and retailers to limit its use. With a little luck, the past week’s mayhem at Marks & Spencer will help to accentuate this trend. One also hopes that companies are taking stock of these events and realising that their business continuity plans must contain analogue backups that allow transactions to continue with cash instore.

Thank you, Nick.

It’s not just regulatory capture. Business continuity just isn’t taken seriously by the government and firms.

That goes for energy security, too, despite Starmer’s “performance” a couple of days ago.

In November 2021, I was offered the post of head of operational risk and resilience policy, which includes cyber security, at the Bank of England. Two days before, I had accepted an offer, also financially better, from my current employer, which I sometimes regret.

I had three interviews, the first two included presentations by me, and was told that “this was an opportunity to raise the profile of the work and team as the governor wasn’t interested”.

It turns out that Whitehall isn’t either, as last year the post of head of cyber security at the Treasury came up for, frankly, a laughable (and same) amount for that level of personal risk (if something goes wrong).

In mid-March, I listened to the BBC give the CEO of Heathrow airport a hard time over the power outage. If the CEO spent money on business continuity, he would not have a job for long. It’s that simple, a point I made to the interview panel and explained how to get around it.

Thanks, Colonel. In researching for this post, I was staggered to learn that the annual Cyber Security Breaches Survey, released by the UK Government, revealed a decline in board-level responsibility for cybersecurity within businesses, even as cyber attacks continue to threaten companies at an unprecedented scale. From Security Brief:

Bringing back cash is always a good idea but there must be systems in place to be able to handle it. I have seen a local supermarket close their doors during a power outage which upon reflection is ridiculous. All that food is still on the shelves. All the customers had the cash to buy that stuff. But because their digital cash registers could not connect to the internet much less power up, they were forced to shut their doors. The way to solve this would be to have cash registers that would operate like modern ones. But if the power supply or the net fell over, then they should be able to process payments through a battery powered backup system. Cards and contactless payments may be out of the question but cash would still be working just fine. Then when the power/net came back online, all the transactions kept on the flash drive could them be transmitted to update the company’s main computers.

Yup – but this type of thinking was apparently beyond the supermarket management’s ability. Instead they took the stupidest and simplest and most wasteful approach. What a gang of maroons. Wasn’t it Sainsbury’s that just shut down rather than come up with a simple solution? If so, it seems a good time to sell their stock considering the incompetence of management.

At least Marks and Sparks figured out how to handle cash transactions.

I shopped at M&S several times in the last week, including during the contactless outage. It was a minor distraction. You just had to insert your card. The employees didn’t know much about the cause. It did not seem to be costing them business.

Thanks for the heads-up, ThatGuy.

“It did not seem to be costing them business.”

This may well have been the case in the store you visited — one out of more than 1,000 in the UK. As M&S itself has admitted, it has paused taking orders from its website and app, which clearly suggests it is costing them some business. The fact that it made this announcement six days after the problems began suggest things are getting worse rather than better. Once the dust settles, the company will presumably have to pay out compensation to the customers most affected. That’s before we even get to the question of what has happened to customer data…