Yves here. During the Trump-tariff-induced market upheaval, eyes were first on equities in many markets around the world and then on Treasuries. What got by comparison passing mention, as opposed to real concern, was the fall of the dollar against most currencies. Exits from US stocks on the scale that it moved the dollar is a meaningful development. Wannabe buyers on dips take note.

As an aside, the claim that Japan dumped Treasuries to pressure the Administration is questionable. It appears to have originated with Charlie Gasparino, with whom we had a major dustup in the runup to the crisis over his dogged defense of Lehman CEO Dick Fuld (see here for details, which includes Gasparino threatening me by phone). Gasparino is not a bond market guy and there’s no reason to think he has advantaged access to information about Japan (which is more hermetic than you’d think). IMHO it is plausible that hedgies dumping Treasuries due to getting margin calls as their basis trade hedges blew up were circulating this rumor so as to shift blame.

By Jonathan Hartley and Alessandro Rebucci, Professor Johns Hopkins University. Originally published at VoxEU

On 2 April 2025, the US announced tariffs on most of its trading partners, creating a major trade policy shock to the world economy. This column shows that the US dollar depreciated on impact, rather than appreciating as expected based on standard theory and prior evidence. The authors argue that this unusual transmission impact of the tariffs on the dollar was driven by foreign equity portfolio rebalancing away from US equities. US trade policy not only needs to consider possible impacts on US safe assets but also risky assets.

On 2 April 2025 – dubbed ‘Liberation Day’ by President Trump – the US announced the imposition of new tariffs on virtually all its trading partners (a 10% tariff applied to imports from 180 countries plus a “reciprocal” tariffs component proportional to each country’s bilateral trade imbalance with the US). This sweeping increase in tariffs constituted the most extensive US tariff hike since the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930 (Baldwin and Navaretti 2025, Evenett and Fritz 2025).

The announcement of a major US trade policy shift provides a unique opportunity to explore how exchange rates respond to a tariff increase. In ongoing research, we employ a high-frequency event study around tariff announcements to measure the currency impacts. By evaluating exchange rate changes in a narrow window around these announcements, we can isolate the effect of the news from other concurrent factors.

Tariffs and Exchange Rates: Standard Theory and Evidence From the First Trump Tariffs

Standard theory predicts that an import tariff should put upward pressure on the tariff-imposing country’s currency: a tariff tends to appreciate (depreciate) the home (foreign) currency, offsetting some of the tariff’s effect on import (export) prices (e.g. Jeanne and Son 2024, among many others). Furthermore, if global trade is largely invoiced in a dominant currency such as the US dollar, the response should be amplified, leading to an even sharper initial appreciation of the home currency (Gopinath et al. 2020). As imports are priced in dollars, the currencies of trading partners need to devalue even more to adjust if the US imposes tariffs.

Evidence from the first wave of Trump tariffs aligns with these predictions. For example, Furceri et al. (2019) and Jeanne and Son (2023) find that higher tariffs are significantly associated with a stronger real exchange rate for the tariff-imposing country. High-frequency analyses similar to ours show that prior US tariff hike announcements generally led to an immediate strengthening of the US dollar and a corresponding weakening of the renminbi, consistent with the theoretical expectation that tariffs appreciate the dollar. Even mere threats or signals of tariffs had effects on currencies: when US officials issued hawkish trade statements, the dollar tended to rise as markets anticipated future tariffs (Egger and Zhu 2020). In short, both economic theory and recent empirical episodes suggest a clear pattern: import tariffs usually appreciate the home currency, partially negating the tariffs’ intended competitive benefits.

The Exchange Rate Impact of the Liberation Day Tariffs

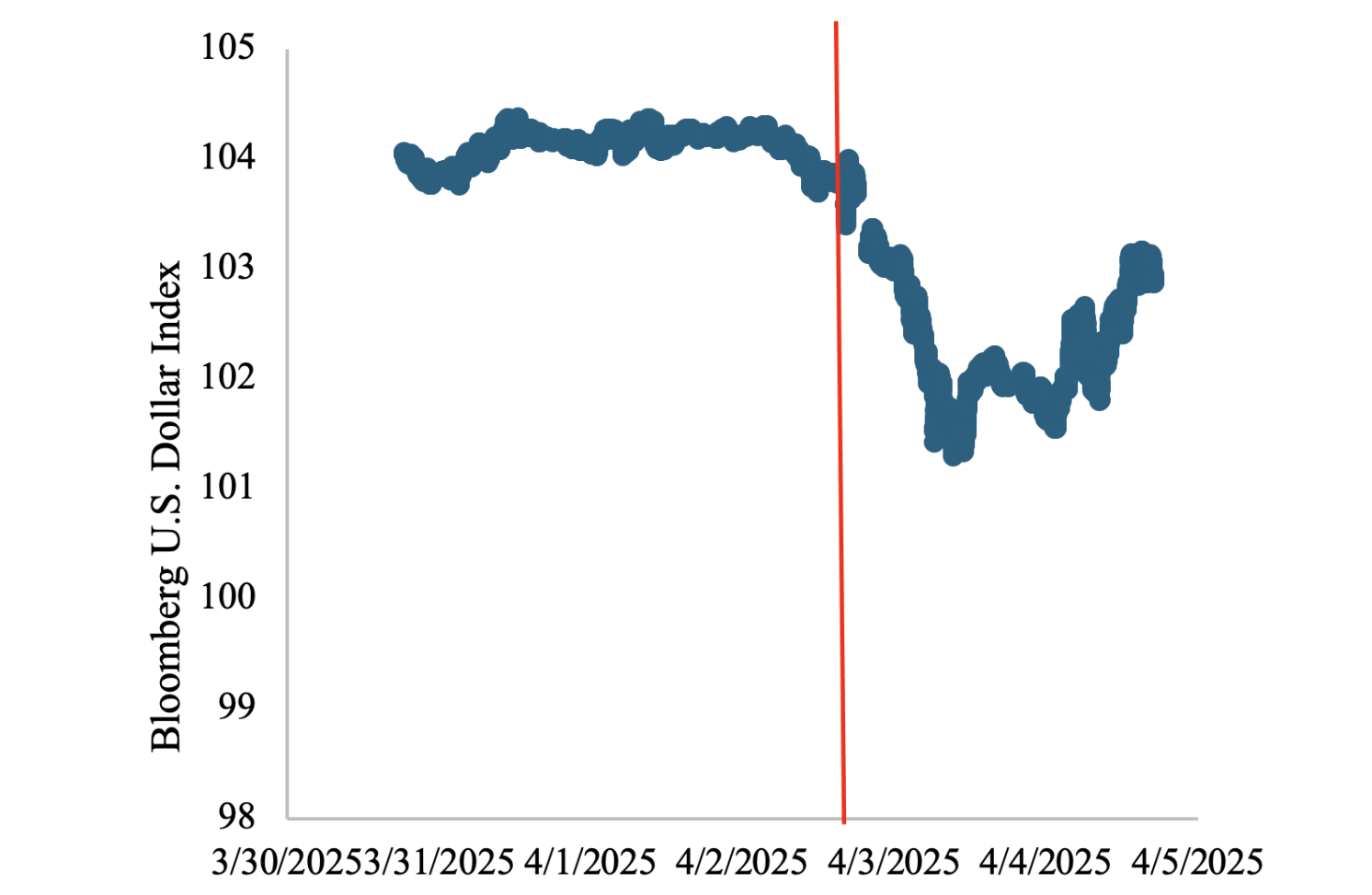

Contrary to the prediction of standard international macroeconomic models and the evidence from the first Trump tariffs, on Liberation Day the dollar effective exchange rate sharply depreciated rather than appreciating (Figure 1). Unpacking the impact on broad dollar indexes by looking at the reaction of the main bilateral pairs reveals a striking divergence in currency responses: most of the G10 currencies appreciated rather than depreciating, while the currencies of many emerging market and developing economies moved in the opposite way. This implies that the US dollar response was driven by large advanced economies, which are much more financially integrated with the US than emerging markets or China.

Figure 1 Bloomberg US Dollar Index on Liberation Day

Note: US Dollar Bloomberg Index, minute-by-minute, 3/31/2025-4/4/2025.

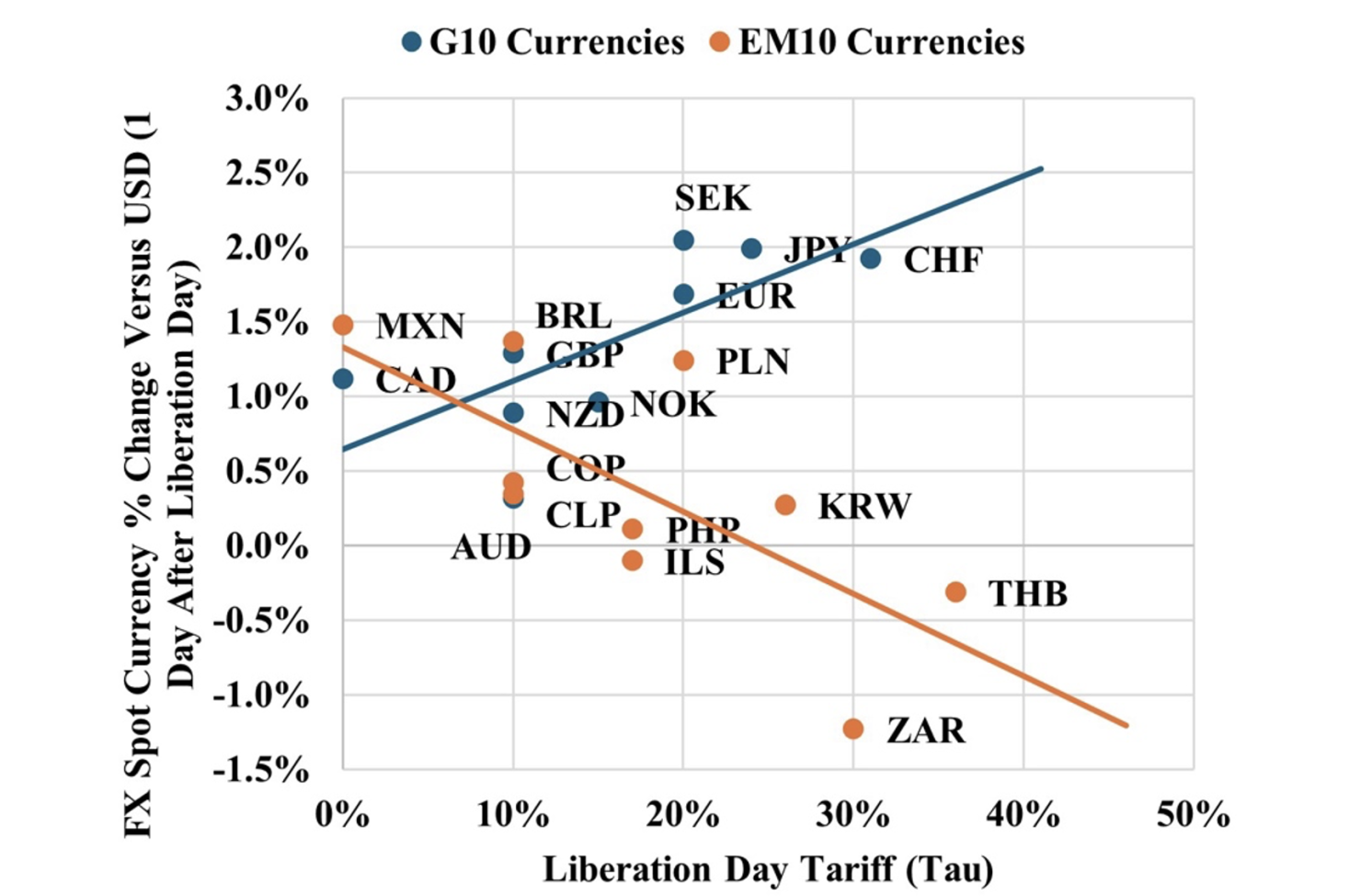

Figure 2 plots the daily change in the bilateral exchange rate against the tariff rates announced on Liberation Day. The figure shows that all G10 currencies appreciated against the US dollar in the 24 hours following the announcement, meaning the dollar weakened against those currencies. In contrast, the most floating emerging market currencies either appreciated less or depreciated against the dollar, meaning the dollar strengthened relative to them. For example, the euro (EUR), Japanese yen (JPY), British pound (GBP), and Swiss franc (CHF) jumped by roughly +1% to +2%, against the dollar, while the Thai baht (THB) and the South African rand (ZAR) fell about –0.5% to –1% , respectively. Additionally, when we looked at a broader set of emerging and developing countries in our sample that have more rigid exchange rate regimes, including China and India, we found only a very weak relationship between the size of the tariff and the magnitude of the currency move. The strong appreciation of the G10 currencies implies that that foreign advanced economy reduced exposure to US dollar-denominated assets, selling dollars in favour of other major currencies to rebalance their portfolios, as trade flows cannot adjust instantaneously.

Figure 2 G10 and free-floating emerging market currency responses

Note: This figure plots one-day bilateral currency changes against the US dollar (an increase means the currency appreciated vs the USD) against the new total tariff rate announced for G10 and the 10 most flexible emerging market currencies according the classification of Ilzetzki et al. (2022).

What Can Explain These Exchange Rate Responses?

The reaction of G10 currencies to the Liberation Day tariffs suggests that other hitherto ignored transmission channels through which tariffs influence exchange rates are now at work, at least in this instance. One obvious much debated possibility is that the second Trump administration’s broader policies and plans, including trade policy, are undermining the safe-haven status of the US dollar and US Treasuries (e.g. Ahmed and Rebecca 2025, Subacchi and van den Noord 2025).

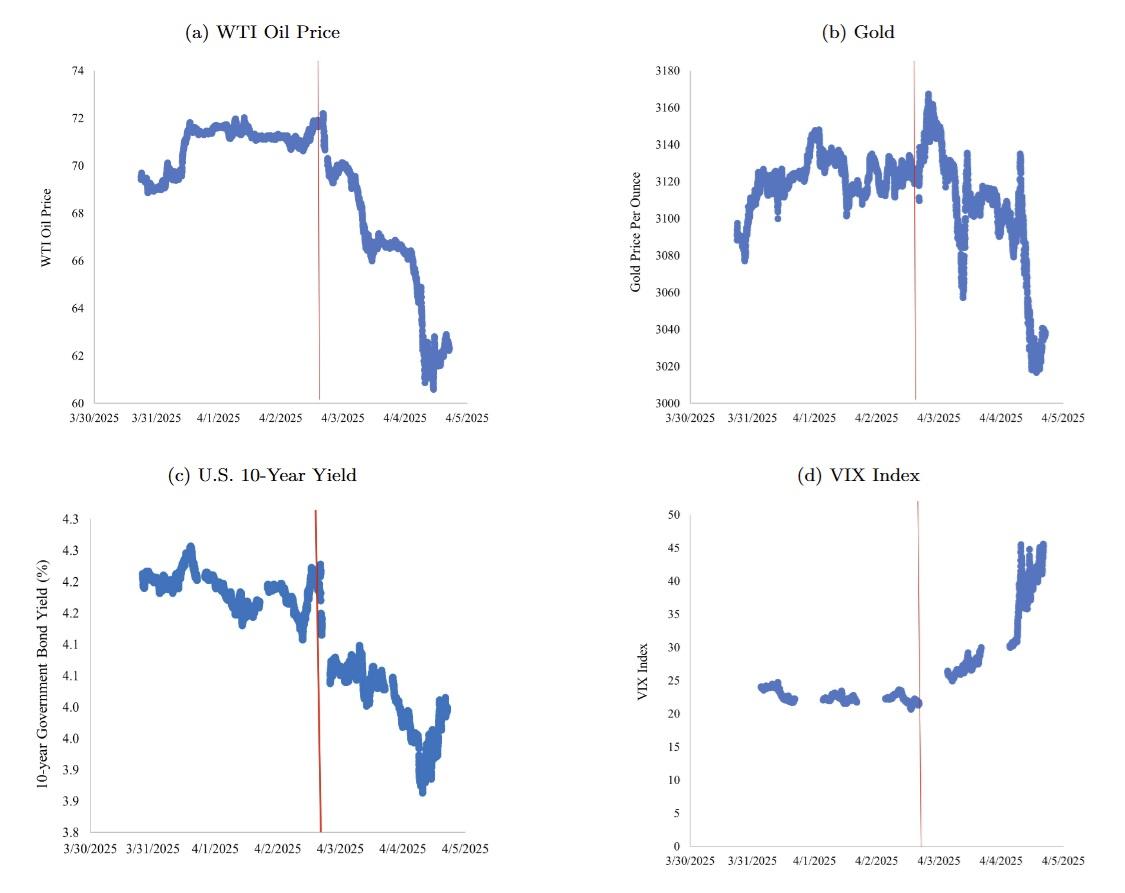

Figure 3 shows the high-frequency impacts of Liberation Day tariff announcement on WTI oil and gold prices, the VIX index, and the US Treasury 10-year yield. The VIX index increased on the announcement, WTI oil fell driven by global demand concerns, gold rose, and US Treasury 10-year yields fell (although US Treasury yields considerably rose during the following week). These responses suggest that global uncertainty spiked, triggering a risk-off episode, and setting off the stage for a typical flight-to-safety response in reserve assets. Thus, this initial evidence is not consistent with the hypothesis that the dollar depreciation on Liberation Day was driven by a breakdown of the correlation between global risk and US safe asset returns.

Figure 3 Liberation Day tariff announcement and flight to safety

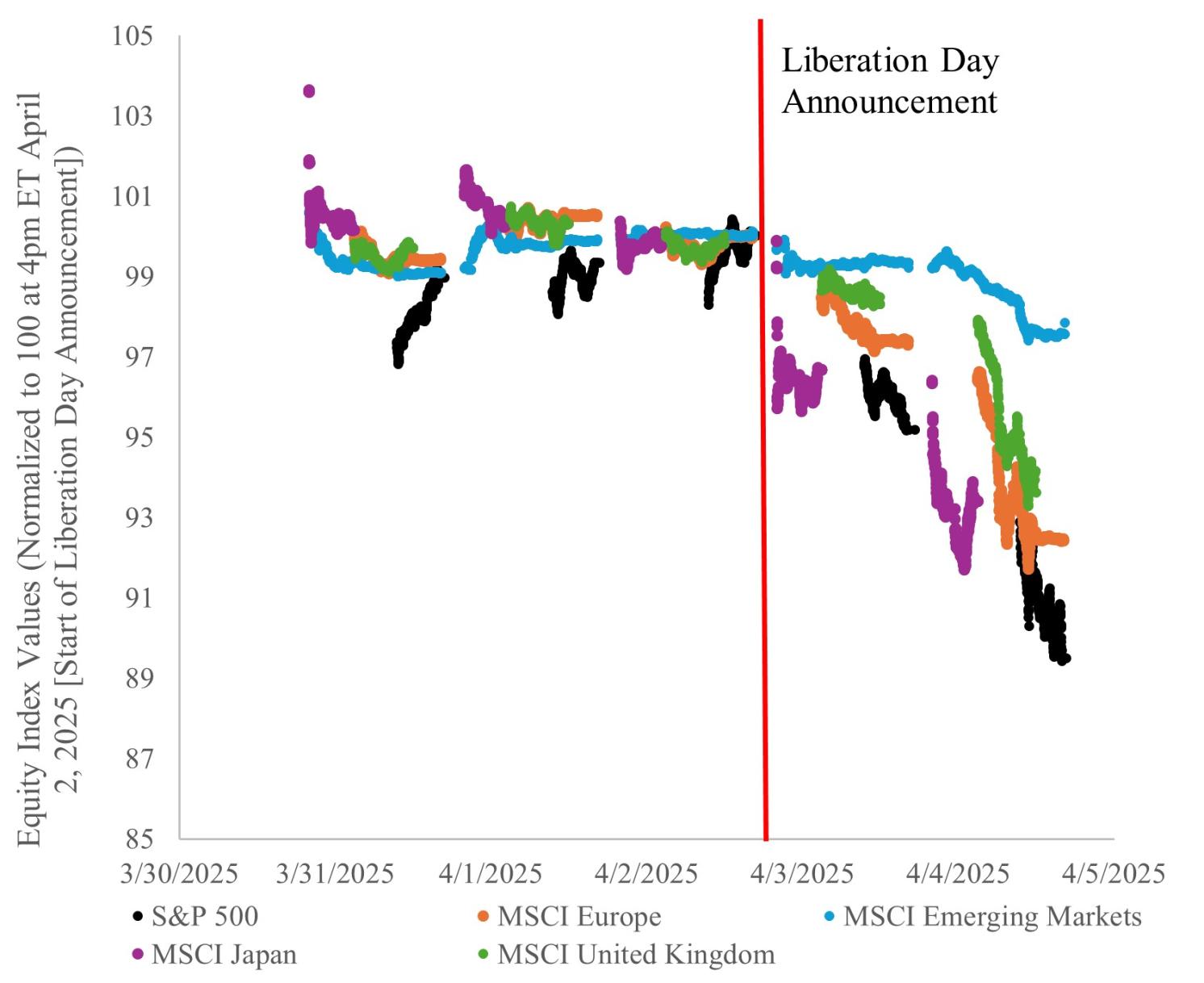

An alternative interpretation is that the G10 depreciation on Liberation Day was driven by equity outflows. Figure 4 plots the S&P500 US equity index, the MSCI Europe Index, the MSCI Japan Index, and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, which all sold off following the Liberation Day tariff announcement. However, US equities fell more than foreign equities on impact.Figure 4 Liberation Day tariff announcement and major equity market indexes

Note: Minute-by-minute data from Bloomberg. 04/02/2025 at 4p.m.=100.

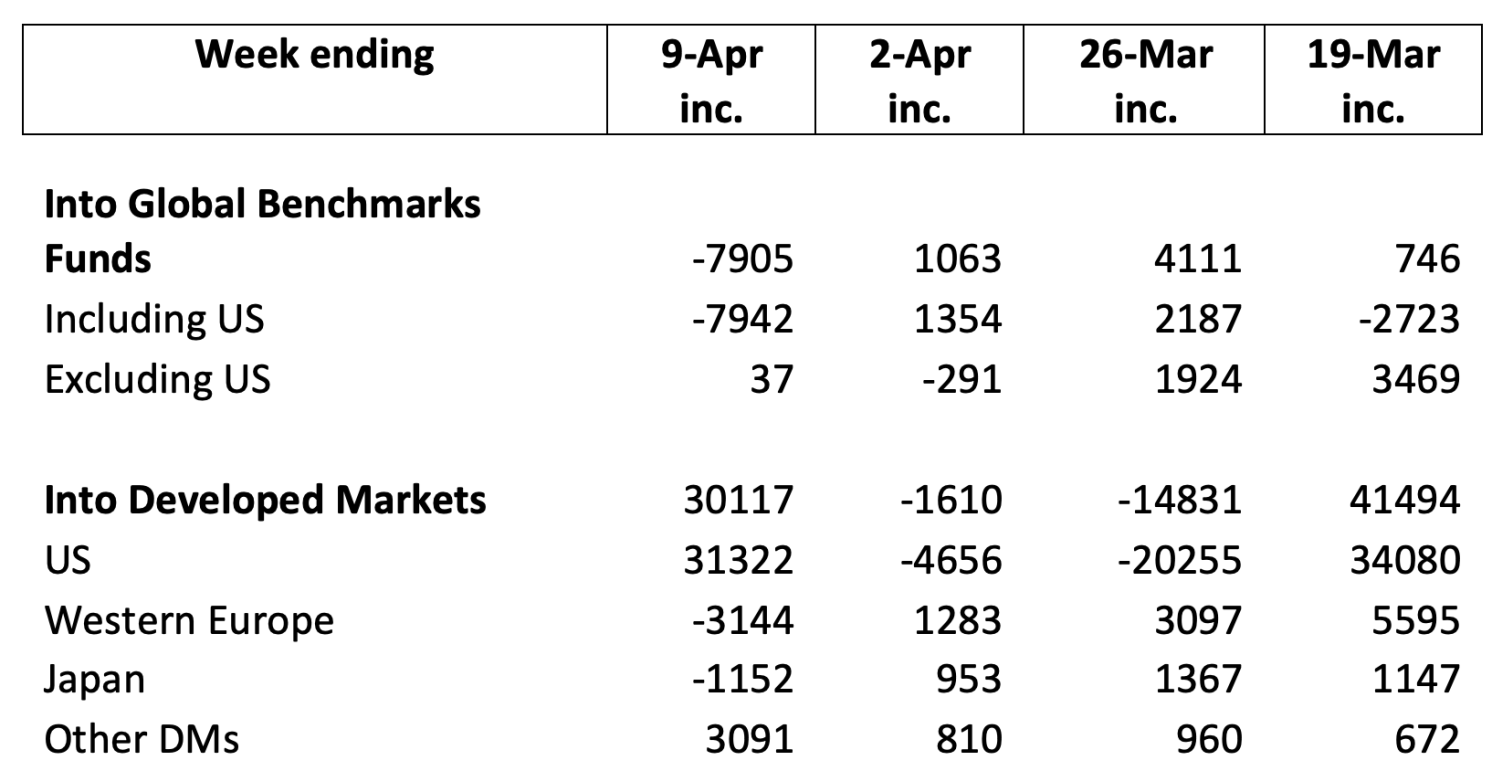

Table 1 is based on data from EPFR (a proprietary data provider of fund flows data) and shows that equity flows into US-focused funds were already declining before Liberation Day, possibly in anticipation of its effects. In contrast, during the same period, Western Europe, Japan, and other developed market funds saw inflows in the run-up to the surprise announcement. The data for the week ending 9 April are clouded by the huge equity rally following the announcement of a 90-day suspension of the Liberation Day tariffs on 9 April. Nonetheless, during the tumultuous second week after the Liberation Day announcement (including 9 April), cumulative flows into Global Benchmark Funds including the US saw a decline of almost $8 billion, while ex-US funds saw a slight increase, in line with the price action in Figure 4. Additionally, Global Benchmark Funds are more likely to influence exchange rate movements due to the multi-currency nature of underlying assets, as Country Funds are more influenced by domestic fund flows.

Table 1 Equity funds flows (domestic and foreign investors)

Source: EPFR and Goldman Sachs Weekly Fund Flows

Standard models of financial integration with trade costs predict that countries which experience an increase in trade costs should see equity outflow and vice versa (i.e. trade costs lead to home bias in equity portfolios). This implies that foreign stock markets should have suffered more than US ones on Liberation Day. However, if a tariff is imposed across the board without distinguishing between final and intermediate products, tariffs can become a cost push or supply chain shock, and stock prices react to supply chain risks. This is especially the case when these inputs are specific and cannot be substituted away (Sauvagnat and Barrot 2015). For example, the share of industrial supplies, capital goods, and transport equipment in US imports from China is more than 70% (Gasiorek and Tamberi 2025).

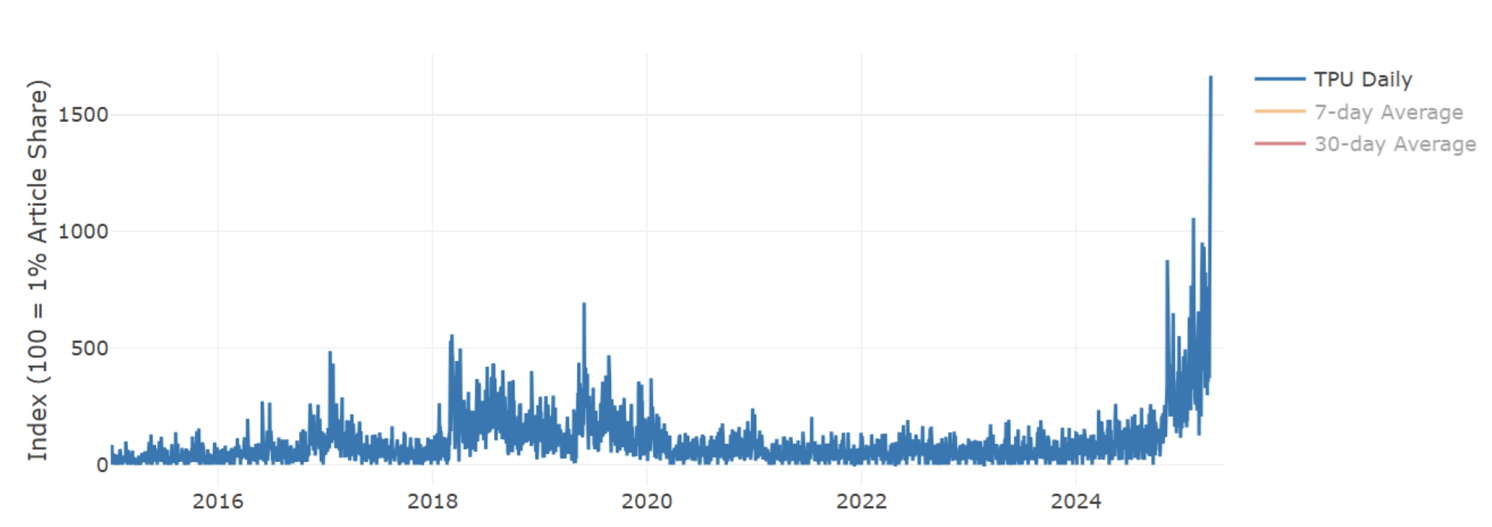

Additionally, tariffs need to be permanent and credible to have the intended macroeconomic effects (Krugman 2025). It is possible that markets doubted the credibility and permanence of the huge Liberation Day tariffs, seeing them as a negotiation tactic or a tool to pursue other policy goals. ‘Incredibly’ high tariffs can simply rise policy uncertainty. Indeed, the Trade Policy Uncertainty Index of Caldara et al. (2024) skyrocketed after Liberation Day (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Trade Policy Uncertainty Index

Source: Caldara et al (2020).

Conclusion

The US dollar response to the Liberation Day tariff announcement was surprising considering both standard theory and prior evidence, and appears to have been driven by a portfolio reallocation away from US equity markets towards other advanced economies. Lower and more volatile expected earnings due to the supply chain implications of the announced across-the-board tariffs and the ensuing uncertainty may have lowering the appeal of US equities to home, and especially foreign, investors. This is evidence that tariff negotiation plans will not only need to consider possible impacts on US safe assets but also risky assets.

See original post for references

It’s a helpful article, but the obvious issue is that even though theory says the following:

Standard theory predicts that an import tariff should put upward pressure on the tariff-imposing country’s currency…

The reality is that economic models involved stylized assumptions to demonstrate a relationship, something of a “ceteris paribus” method. So a relationship can be plenty real, but if numerous other things are going on or if the size of something is much larger than ever examined in a model and breaches levels where nonlinear effects emerge, of course a predicted effect may not materialize. For example, of course a firm that improves a product should see better sales of the product. But if the firm simultaneously triples the price, the prediction that higher quality will lead to higher sales will not be apparent due to the other effects.

And that’s why economics, especially macroeconomics, is such a difficult social science; there’s no such thing as a perfectly controlled experiment, just better and worse statistical analysis.

“Jeffrey Sachs Goes Off, Roasts Donald Trump’s Trade Talk, Says ‘Mickey Mouse Is Smarter Than Him'”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gNson4TqUO4