Yves here. This post usefully goes a bit deeper into the regulatory system for food additives. It should come as no surprise that in the US, it remarkably permissive.

The article alludes to but does not address the idea that some foods, particularly snack foods, are engineered to seem very rewarding, such as the mouth feel of a Cheeto. So there’s an additional layer of issues: not only can additives be directly harmful to health, but they can be indirectly damaging by being incorporated to encourage excessive consumption, which then produces overweight and obesity.

By Charles Schmidt, a senior contributor to Undark and has also written for Science, Nature Biotechnology, Scientific American, Discover Magazine, and The Washington Post, among other publications. Originally published at YouTube in September, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. took aim at U.S. health agencies that he said have allowed for the mass poisoning of American children. Standing behind packages of Cheez-Its, Doritos, and Cap’n Crunch cereal displayed on a kitchen counter, the future head of the Department of Health and Human Services warned that chronic disease rates in the United States have soared. “How in the world did this happen?” Kennedy asked. Many of our chronic ailments, he asserted, can be blamed on chemical additives in processed foods. “If we took all these chemicals out,” he said, “our nation would get healthier immediately.”

During his Senate confirmation hearings in January, Kennedy singled out a Food and Drug Administration standard by which companies can introduce new additives to foods without notifying regulators or the public. The standard, called “generally recognized as safe,” or GRAS, was adopted in 1958 and geared initially towards benign substances such as vinegar and baking powder. However, most of the chemical additives introduced in recent decades passed through the so-called GRAS loophole: The FDA requires manufacturers to affirm GRAS additives are safe, but the companies don’t have to release the data, and they are in effect self-regulating. In 2013, the Pew Charitable Trusts estimated that more than 10,000 additives were in processed foods and that 3,000 of them had never been reviewed by the FDA. Out of that group, Pew estimated that 1,000 were self-affirmed as GRAS by additive manufacturers.

The GRAS system came into effect “well before the majority of calories consumed by adults and children were in the form of ultra-processed food products,” Jennifer Pomeranz, a public health attorney and associate professor at New York University’s School of Global Public Health, wrote in an email to Undark. By self-affirming that a given additive is GRAS, companies can avoid time-consuming regulatory submissions. The process is easier and cheaper for companies, Pomeranz wrote, but it undermines “public trust of the food supply.”

On March 10, Kennedy directed the FDA to explore rule-making strategies for eliminating the self-affirmed GRAS pathway for food ingredients, claiming the move would provide transparency for consumers. At a March meeting with food industry executives, he also cited the elimination of artificial dyes — which go through a different FDA approval process — from foods as a top priority.

Kennedy’s goal to rid the food supply of chemical additives is winning accolades from nutrition experts, but it also raises challenging questions. The FDA would need more money and staff to expand oversight of food chemicals, which flies in the face of President Donald Trump’s promise to cut — not increase — federal spending.

Meanwhile, questions remain about how much of a role food additives actually play in chronic disease and whether tightening the GRAS loophole would really help. Food additives are a “piece of the puzzle,” said Kathleen Melanson, a nutrition scientist and professor at the University of Rhode Island. But, she added in an email, “other aspects of food and diets should not be ignored.” Still, the focus on food additives strikes a chord with those who say changes to FDA policy are long overdue. “There’s an opportunity to get things done,” said Emily M. Broad Leib, a clinical professor at Harvard Law School. “It’s generated such a response that’s been, I think, echoed across the political spectrum.”

Chemical food additives fall into a few general categories, including dyes, sweeteners, and emulsifiers that improve food texture and shelf life. These chemicals began appearing in foods well over a century ago, and over time, they helped to fuel the rise of highly processed foods. Children and adolescents are now among the biggest consumers.

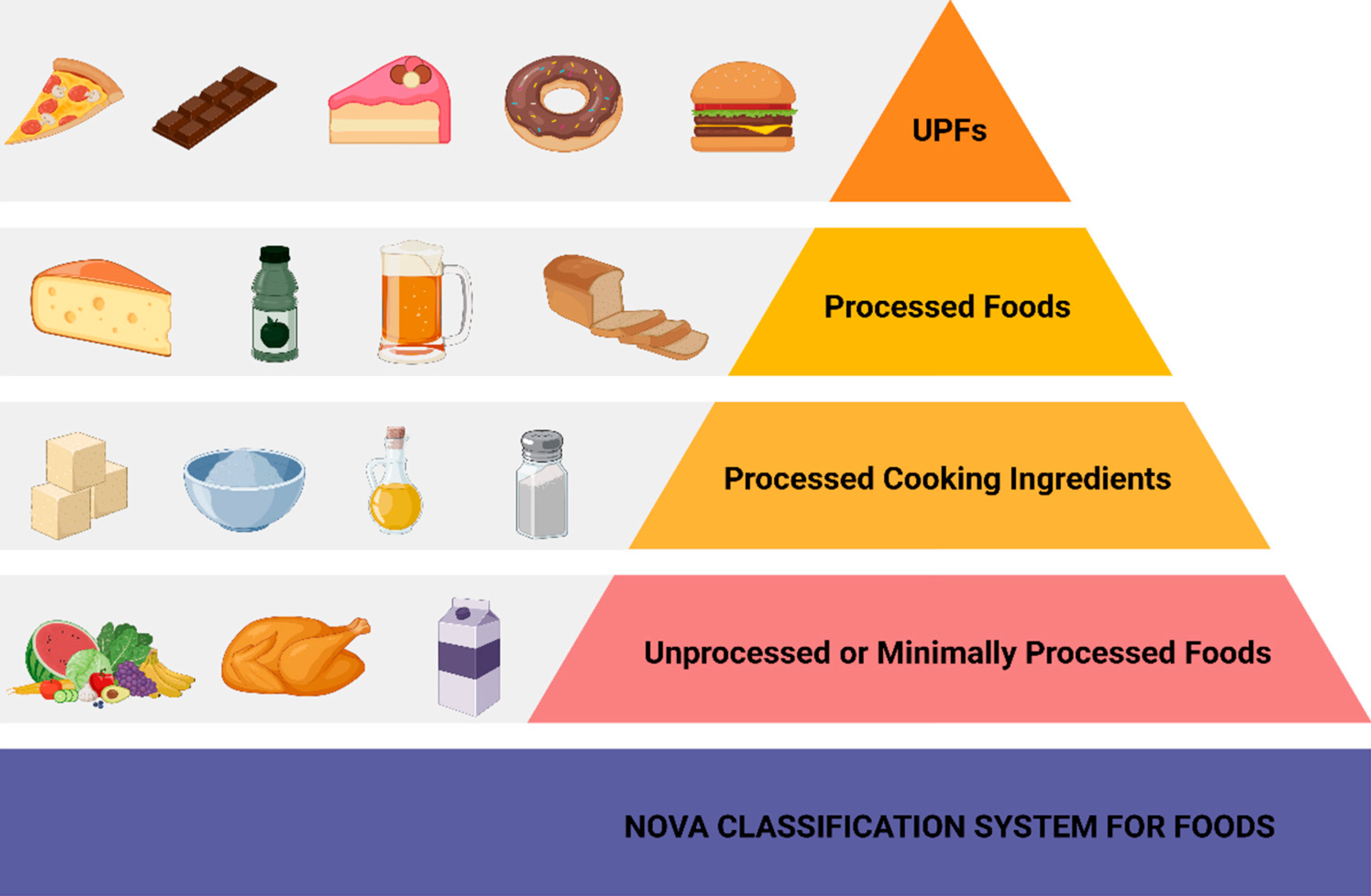

A U.S.-based study showed that in 2018, people aged 2 to 19 got 67 percent of their calories from ultra-processed foods as defined by Carlos Monteiro, an epidemiologist and emeritus professor at the University of São Paulo’s School of Public Health, and his co-authors. The team’s widely cited classification scheme — named Nova — divides food into four categories. The first category includes natural or minimally processed foods, whereas ultra-processed foods at the opposite end of the spectrum comprise “formulations of often chemically manipulated cheap ingredients, such as modified starches, sugars, oils, fats, and protein isolates, with little if any whole food added. These foods are made palatable and attractive by using combinations of flavours, colours, emulsifiers, thickeners, and other additives,” Monteiro and two University of São Paulo colleagues wrote in a 2024 editorial. Examples include soft drinks, chicken nuggets, frozen meals, packaged snacks, and ready-to-eat cereals.

Designed for what Melanson described as “hedonic appeal,” ultra-processed foods stimulate reward centers in the brain; some scientists have even suggested that such foods are addictive. Research has associated ultra-processed foods with obesity, type 2 diabetes, cancer, and depression. Kennedy’s attacks center less on the foods’ nutritional deficiencies than on the supposed toxicity of their synthetic ingredients.

Other regulators increasingly share his concerns. In March, West Virginia took the unprecedented step of banning seven food dyes: Blue No. 1, Blue No. 2, Green No. 3, Yellow No. 5, Yellow No. 6, Red No. 40, and Red No. 3. The ban goes into effect in 2028, and at least 20 other states are considering similar measures, according to The New York Times. In 2023, California banned four synthetic food substances: potassium bromate, a conditioner that helps flour rise during baking; brominated vegetable oil, or BVO, a stabilizer for artificial flavors; propylparaben, an antimicrobial preservative; and Red Dye No. 3, a colorant historically derived from coal tars that is used in soft drinks, candy, and drugs.

The FDA followed suit with its own ban on Red Dye No. 3 in January of this year, citing evidence that the chemical causes cancer in rats. (The FDA noted the way the dye causes cancer in rats does not happen in humans.) Used in food, drugs, and cosmetics for over a century, Red Dye No. 3 was first shown to be carcinogenic in rodents during a study conducted in 1977. After being exposed to the dye in utero, rats were fed a daily dose (measured by animal weight) that was more than 24,000 times as high as what the World Health Organization currently deems acceptable for human consumption. In all, 16 out of 69 male rats (but none of the females) developed thyroid tumors after a lifetime of exposure, though fewer rats developed tumors at lower doses. The FDA saw fit to ban Red Dye No. 3 from cosmetics in 1990, while allowing the dye to remain in food for over 30 years.

The recent ban has drawn mixed reactions. Roger Clemens, an adjunct professor of pharmacology and pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Southern California and past president of the Institute of Food Technologists, an industry trade group, said that Red Dye No. 3 has never been shown to cause cancer in humans. But Maricel Maffini, a biochemist and independent consultant, said the FDA is bound to a legal provision called the Delaney Clause, which prohibits any food additive with evidence of carcinogenic effects in animals or humans, regardless of the dose. The provision assumes “that even a single molecule of a carcinogen could cause cancer,” Maffini said, so when it comes to allowing such compounds in food, the answer is “no — period.” The FDA and HHS did not provide answers to emailed questions submitted by Undark during the preparation of this story.

The Nova classification scheme, defined by Carlos Monteiro and his co-authors in 2018, divides food into four categories. The first category, at the bottom of this pyramid, includes naturally or minimally processed foods, whereas ultra-processed foods (UPFs) at the top of the pyramid contain “formulations of often chemically manipulated cheap ingredients,” such as modified starches, sugars, oils, fats, and protein isolates,” Monteiro wrote. Visual: Vallianou et al, Biomolecules 2025

Even before the state and federal bans took effect, food companies were phasing Red Dye No. 3 out voluntarily. The Hershey Company, for instance, told CBS News that it stopped using the dye in 2021. Kantha Shelke, a senior lecturer at Johns Hopkins University and founder of a food science and research firm, said companies often apply a “stealth approach” when pulling controversial ingredients off the market. A quiet transition, she wrote in an email, helps to ensure that existing inventory won’t be “rejected by consumers while the reformulated products gradually appeared on store shelves.”

Companies have been quietly phasing out other food dyes as well, including Yellow Dye No. 5, which Kennedy singled out in his YouTube video for allegedly causing “tumors, asthma, developmental delays, neurological damage, ADD, ADHD, hormone disruption, gene damage, anxiety, depression, intestinal injuries.” Also called tartrazine, and also historically derived from coal tars, the dye first appeared in foods during the early 20th century. By the 1970s, mounting evidence had linked the dye with health problems such as urticaria, also known as hives. Companies started phasing out tartrazine more than a decade ago, according to Shelke, who is also a member of the Institute of Food Technologists, in some cases replacing it with natural alternatives such as paprika and turmeric. However, the bright yellow dye is still found in many conventional items, Shelke wrote in an email, “including sodas, candies, cereals, Jell-O, and snack foods.” A recent analysis by The Wall Street Journal found that more than one in 10 products in a federal database of 450,000 foods and beverages contained at least one artificial dye. Among these products, 40 percent used three dyes or more.

While cancer fears propelled the demise of Red Dye No. 3, health worries over tartrazine and other dyes center mostly on neurologically driven behavioral problems in children. In a book published in 1975, San Francisco-based pediatric allergist Benjamin Feingold blamed behavioral symptoms on intake of synthetic food additives and dyes by the typical American child. He became a minor celebrity championing the “Feingold diet,” which was free of these substances.

Yet as a remedy for the prevention and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, the Feingold diet met with controversy, especially among skeptical physicians who felt the supporting evidence was inadequate. Years of ensuing research into dietary interventions for ADHD generated conflicting results. In 2010, the European Union adopted a precautionary stance by requiring that foods with synthetic food dyes be labeled to warn of possible adverse effects on activity and attention in children. But despite the urging of groups such as the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Center for Science in the Public Interest, the FDA has yet to require similar labels.

One paper suggesting that dyes and behavioral effects might be related, which has been cited dozens of times, was co-authored in 2012 by Joel Nigg, a professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health & Science University. Nigg and his team compiled dozens of research studies investigating the role of dietary additives on ADHD symptoms in children. Based on the results of this meta-analysis, Nigg and his colleagues concluded that roughly one third of children with ADHD might respond to a restriction diet free of synthetic additives, and that 8 percent of those children may be sensitive to food dyes specifically. The evidence was too weak to justify policy action “absent a strong precautionary stance,” they wrote, but also “too substantial to dismiss.”

A later 2022 review led by scientists at the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment reached more definitive conclusions. The OEHHA team compiled 27 clinical trials of children exposed to synthetic food dyes. Most of the trials had dosed children directly with dyes or a placebo on alternating schedules. Parents, teachers, and, in some cases, trained specialists assessed the children’s behavior and in some studies were unaware of when the dye exposures were occurring. Mark Miller, a pediatrician who led the OEHHA review, said doses tested during many of the trials mimicked real life exposure to synthetic food dyes. The dyes had no effect on some children, while others had measurable impacts on attention, impulsivity, learning, memory, and hyperactivity, he said. The combined evidence favoring a link between synthetic dyes and neurobehavioral effects “is very strong,” said Miller, who is now an associate professor at the University of California, San Francisco. The FDA’s exposure limits for these chemicals, called acceptable daily intakes, “may not be adequate to protect children,” he said.

Clemens is sharply critical of such meta-analyses, claiming they “aren’t worth the paper they’re printed on.” Rather than “looking at the totality of the evidence” — for example, all the published studies pertaining to a given research question — meta-analyses are restricted to a select subset of individual studies meeting the review authors’ pre-defined inclusion criteria, he said. Clemens recognizes that some people are sensitive to food coloring but also questioned whether scientists know the mechanism by which dyes might exert behavioral effects.

Still, possible mechanisms have been proposed. John Warner, a pediatrician and emeritus professor at Imperial College London, and other researchers published evidence suggesting that food dyes might lead to hyperactivity by stimulating the release of histamine, which then binds to receptors in the brain. Histamine is familiar for its roles in allergies and asthma, but the neurotransmitter’s receptors “have been associated with changes in behavior,” Warner said. Warner co-authored a study during which children 3, 8, or 9 years old were given fruit drinks supplemented with either food dyes or a placebo. The dyes boosted hyperactivity among some children. Results from an additional study, published in 2010, showed that the most affected children had genetic variants — not specifically associated with ADHD — that make it difficult for them to break down histamine. These results suggest that food dyes trigger histamine releases that, in turn, might overstimulate those receptors in genetically prone children, resulting in impulsive and hyperactive behavior, Warner explained.

An ongoing study based in Europe might generate further insights into the health effects of food additives. Launched by French researchers in 2009, the NutriNet–Santé study is among the world’s largest investigations of nutrition and health, with more than 100,000 participants. The enrolled subjects use barcode readers to scan the food items they consume. “We can extract information from the packaging related to which additives they were exposed to,” said Bernard Srour, an epidemiologist at the Université Sorbonne Paris Nord and a co-investigator of the study. The NutriNet–Santé team measured levels of most of the approximately 400 additives approved in Europe for packaged food items, allowing them to quantify exposures precisely. Srour declined to comment on an ongoing investigation of synthetic dyes. But he singled out findings on emulsifiers and artificial sweeteners, describing them both as being “associated with an increased risk of human disease.”

Emulsifiers turn hydrophobic (water-hating) and hydrophilic (water-loving) substances into stable mixtures. Mayonnaise, for instance, relies on a natural emulsifier called lecithin in egg yolks to hold the condiment together so that it doesn’t separate into its watery and oily components. Other natural emulsifiers include carrageenan (made from seaweed), locust bean gum (from carob seeds), mono- and diglycerides (from fatty acids and glycerol), guar gum (from guar beans), and xanthan gum, which is produced by fermenting a bacterium called Xanthomonas campestris.

Some evidence suggests that some emulsifiers damage protective layers of mucus on intestinal surfaces, potentially allowing bacterial toxins, including lipopolysaccharides, to leak into the bloodstream. When lipopolysaccharides bind to receptors on immune cells, they can trigger inflammatory reactions that boost “the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes,” said Katherine Maki, a clinical investigator at the National Institutes of Health. Research by the NutriNet–Santé researchers provides supporting evidence. In 2024, the team reported that dietary exposures to carrageenans, guar gum, and xanthan gum elevated the risk of type 2 diabetes for adults in the study.

In Shelke’s view, synthetic emulsifiers may pose comparatively greater health risks. Effective in small amounts and cheaper to use than their natural alternatives, synthetic emulsifiers do not exist in nature, and our microbiome does not have any way to process them, Shelke wrote in an email. Andrew Gewirtz, an immunologist and researcher at Georgia State University, pointed out that unlike natural emulsifiers such as lecithin, which can be broken down by microbes in the small intestine, synthetic emulsifiers pass unrecognized through the gastrointestinal tract and can spend 7 to 8 hours in the colon, interacting with bacteria. In animal models, emulsifiers have been shown to change bacterial gene expression, he said, causing microbes to “express virulence factors that make them more aggressive.”

Scientists believe this may also happen in people. Gewirtz advises consumers to avoid carboxymethylcellulose and polysorbate-80 but also suggests people minimize consumption of guar and xanthan gums. Among natural emulsifiers, these “have the biggest impact in mice,” he said, adding “we don’t know why or how well that translates to humans.”

Shelke, meanwhile, cited an oft-repeated phrase in toxicology, which is that the dose makes the poison. For instance, humans have been consuming xanthan gum in its natural form for millennia, she noted in an email, but not in the concentrated doses now used in food products. Similarly, synthetic emulsifiers consumed in trace amounts can perform their function without harming the microbiome, “whereas excessive exposure may have adverse effects,” she wrote.

And what of the familiar artificial sweeteners found in packets on restaurant tables and on the ingredient lists of products marketed as low calorie? Many varieties have been introduced over the years, but health evidence on these compounds lacks consensus. For instance, citing high-dose animal studies and limited evidence of an association with liver cancer in humans, the WHO’s International Agency for Research on Cancer classified aspartame as a possible human carcinogen, while the FDA maintains that aspartame is safe when consumed “under the approved conditions of use.” Cancer worries aside, sweeteners may also alter gut microbiomes in ways that disrupt the body’s control of blood sugar, potentially leading to “type 2 diabetes as well as weight gain and obesity,” Jotham Suez, an assistant professor for molecular microbiology and immunology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, wrote in an email.

Evidence from the NutriNet–Santé cohort and other studies also point to metabolic downsides from artificial sweeteners. Substances that taste sweet trigger the brain to release insulin, a hormone that keeps blood sugar under control. Hundreds of times sweeter than table sugar, products such as aspartame and sucralose (Splenda) can trigger the brain to over-react and release more insulin than necessary. And that excess insulin, Shelke said, “can then wreak havoc on the other parts of my body.” But if people consume artificial sweeteners and other additives in small amounts once in a while, “that’s OK,” she added.

In yet another video, posted on X, Kennedy vowed to make American food as healthy as it was when he was a child. But teasing causation out of massive epidemiological datasets is difficult. Moreover, distinguishing the effects of additives on chronic disease from those of caloric density and high levels of saturated fat, sugar, and salt in ultra-processed foods will also require longitudinal studies that collect human data over time, Maki and colleagues wrote in a 2024 comment article. In the meantime, will imposing new restrictions on additives — including by tightening the GRAS loophole — generate tangible health benefits?

Kennedy described his March directive to the FDA as one that would promote “radical transparency to make sure all Americans know what is in their food.” Kennedy also said he would direct the FDA and the National Institutes of Health to ramp up post-market assessments of current GRAS chemicals, with an aim towards identifying compounds that are making Americans sick so consumers and regulators can make informed decisions.

Harvard Law School’s Broad Leib said in an email that she is “fully supportive of RFK’s letter directing FDA to see what they can do to address the GRAS pathway.” She also supports any effort to increase post-market surveillance, “but I think the devil is in the details on whether they are actually going to do such surveillance and enforcement in a way that is impactful.” Achieving these goals will be extremely difficult “given the large staffing cuts that have been proposed at FDA and across HHS,” she added.

“[I] think the truth is that we have no idea if tightening up these loopholes will have any effect on chronic disease in America,” Pieter Cohen, an internist at the Cambridge Health Alliance in Massachusetts and prominent commentator on FDA policy, wrote in an email. The strategy might generate transparency for consumers, Cohen noted, allowing them to look for GRAS substances on food labels. Perhaps consumers might avoid ultra-processed diets upon realizing that what they think of as food is “actually just assorted chemicals,” he wrote. But evidence shows consumers in the U.S. are also buying ultra-processed foods in greater amounts. Whether visual, textural, or flavorful, “sensory-related industrial additives are the ones that draw you in,” said Elizabeth Dunford, an adjunct assistant professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Dunford and her co-authors reported in 2023 that nearly 60 percent of foods purchased by U.S. households contains chemical additives — an amount that grew by about 10 percent between 2001 and 2019. At the same time, there was a more than 10 percent decrease in the proportion of products purchased that contained zero additives, she and her team found.

How will consumers react to foods without the familiar look, feel, and tastes they’ve become accustomed to? People who don’t see the bright, pristine colors that artificial dyes provide might “think the food is adulterated,” Shelke said. Still, the GRAS system could be better monitored to provide assurances of integrity, because when it comes to food safety, she said, “trust is all we have.”

My interpretation is that Kennedy is actually applying appropriately GRAS, which was intended for minimally processed foods, not novel chemical additives. If they are so important to industry, let them prove they are safe by an independent laboratory (not the producer).

I am wondering where all these additives are manufactured. If China is a source, or really any other country, the Trump tariffs could be put to good use by raising the tariffs so high on these products that the companies using them to manufacture food would stop using them. Also, tariffs on imported ultra processed food could be increased to become unaffordable to the US population at large. My two cents.

The text itself looks kinda obese…?

Font shaming?

I remember going to see the movie “The Informant!” and having my young kid with me. The ticket guy (this was at an independent theater, not a mall) asked, “are you sure you want him to see that?” So me, having a bit of info about what the movie was supposed to be about, leaned in and asked, “why, what should I know?” He said, “they say the f word”. I said, “no prob, we’re from the south side!”

It was a dark comedy based upon a true story of a real person at a company based in central Illinois, and the f word was the least of it. HFCS for the win!

After the UK joined the then EEC and cut loose the Commonwealth, countries like Australia fell into the orbit of the USA.

Their iconic chocolate bars, TimTams were outlawed in EU because of worries about possible carcinogenic aspects of additives. You can only get them in specialised “Australiana” shops in London here that got a specialist grandfather clause.

I dunno about cancer but they sure caused my nephews to go hyperactive….. up until age 8 or so they didn’t learn my name and knew me as “Uncle TimTam”. My sister probably hated me.

Not a keto follower but I think Atkins had one excellent bit of advice: shop in the produce aisle and the meat aisle and nothing in between.

Oh no, we are stuck in the bold text realm!

Ultra-processed foods should be taxed like soda to make people healthier.

I shop in the organic produce aisle and that’s it. There are no lists of ingredients. A cabbage, a zucchini, a cauliflower etc, they are what they are. What organic is remains another question. I have a girlfriend who does not cook and only eats processed packaged ‘foods’. She’s obese. If I got any thinner I’d disappear.